Arxiv:2101.08582V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 23 Apr 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

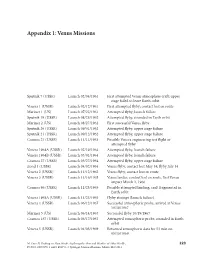

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Investigating Mineral Stability Under Venus Conditions: a Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies Erika Kohler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies Erika Kohler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Geochemistry Commons, Mineral Physics Commons, and the The unS and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Kohler, Erika, "Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1473. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1473 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Space and Planetary Sciences by Erika Kohler University of Oklahoma Bachelors of Science in Meteorology, 2010 May 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________ Dr. Claud H. Sandberg Lacy Dissertation Director Committee Co-Chair ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. Vincent Chevrier Dr. Larry Roe Committee Co-chair Committee Member ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. John Dixon Dr. Richard Ulrich Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Radar studies of the surface of Venus have identified regions with high radar reflectivity concentrated in the Venusian highlands: between 2.5 and 4.75 km above a planetary radius of 6051 km, though it varies with latitude. -

18Th Meeting of the Venus Exploration Analysis Group (Vexag)

18TH MEETING OF THE VENUS EXPLORATION ANALYSIS GROUP (VEXAG) Program and Abstracts LPI Contribution No. 2356 18th Meeting of the Venus Exploration Analysis Group November 16–17, 2020 Institutional Support Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Convener Noam Izenberg Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory Darby Dyar Mount Holyoke College Science Organizing Committee Darby Dyar Planetary Science Institute, Mount Holyoke College Noam Izenberg JHU Applied Physics Laboratory Megan Andsell NASA Headquarters Natasha Johnson NASA Goddard Jennifer Jackson California Institute of Technology Jim Cutts Jet Propulsion Laboratory Tommy Thompson Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Compiled in 2020 by Meeting and Publication Services Lunar and Planetary Institute USRA Houston 3600 Bay Area Boulevard, Houston TX 77058-1113 This material is based upon work supported by NASA under Award No. 80NSSC20M0173. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this volume are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Lunar and Planetary Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under a cooperative agreement with the Science Mission Directorate of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. ISSN No. 0161-5297 Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/vexag2020/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. -

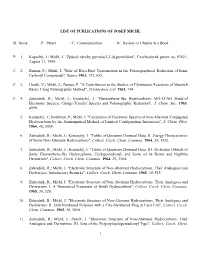

LIST of PUBLICATIONS of JOSEF MICHL B: Book P: Patent C

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS OF JOSEF MICHL B: Book P: Patent C: Communication R: Review or Chapter in a Book P 1. Kopecký, J.; Michl, J. "Zpùsob výroby pyrrolo(2,3-d)-pyrimidinù", Czechoslovak patent no. 97821, August 11, 1959. C 2. Zuman, P.; Michl, J. "Role of Keto-Enol Tautomerism in the Polarographical Reduction of Some Carbonyl Compounds", Nature 1961, 192, 655. C 3. Horák, V.; Michl, J.; Zuman, P. "A Contribution to the Studies of Elimination Reactions of Mannich Bases, Using Polarographic Method", Tetrahedron Lett. 1961, 744. C 4. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J.; Koutecký, J. "Fluoranthene-like Hydrocarbons: MO-LCAO Study of Electronic Spectra, Charge-Transfer Spectra and Polarographic Reduction", J. Chem. Soc. 1963, 4998. 5. Koutecký, J.; Hochman, P.; Michl, J. "Calculation of Electronic Spectra of Non-Alternant Conjugated Hydrocarbons by the Semiempirical Method of Limited Configuration Interaction", J. Chem. Phys. 1964, 40, 2439. 6. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J.; Koutecký, J. "Tables of Quantum Chemical Data. II. Energy Characteristics of Some Non-Alternant Hydrocarbons", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1964, 29, 1932. 7. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J.; Koutecký, J. "Tables of Quantum Chemical Data. III. Molecular Orbitals of Some Fluoranthene-like Hydrocarbons, Cyclopentadienyl, and Some of its Benzo and Naphtho Derivatives", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1964, 29, 3184. 8. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J. "Electronic Structure of Non-Alternant Hydrocarbons, Their Analogues and Derivatives. Introductory Remarks", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1965, 30, 515. 9. Zahradník, R.; Michl, J. "Electronic Structure of Non-Alternant Hydrocarbons, Their Analogues and Derivatives. I. A Theoretical Treatment of Reid's Hydrocarbons", Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. -

WYSE ”Academic Challenge' 2002 Regional Solutions Key 1. Consider

WYSE ‘Academic Challenge’ 2002 Regional Solutions Key 1. Consider the following liquids and their respective densities: pentane, d = 0.626 g/mL; carbon tetrachloride, d = 1.88 g/mL; diiodomethane, d = 3.33 g/mL; mercury, d = 13.7 g/mL. If equal masses of each liquid are compared, which liquid occupies the largest volume? a. pentane b. carbon tetrachloride c. diiodomethane d. mercury e. all occupy the same volume Solution: Of the listed liquids, pentane has the smallest density, and it will occupy the largest volume (volume = mass/density). 2. A substance X melts at 10oC and boils at 108oC. This substance is soluble in water and its aqueous solutions do not conduct electricity. This substance is best classified as a(n): a. acid b. ionic compound c. metal d. molecular compound e. network covalent compound Solution: The physical data are consistent with a molecular compound. Metals and network covalent substances are not water soluble; most are solids at and above room temperature. Acids and ionic compounds are electrolytes in water. 3. Which property of a sample of water remains the same when it changes from a solid (ice) to a gas? a. density b. mass c. enthalpy d. volume e. all remain the same Solution: all but mass change as a consequence of this phase change. Volume increases dramatically and density decreases. A significant amount of heat must be absorbed to transform ice to a gas. 4. 3.54 x 10-4 is the same as: a. 0.0000354 b. 0.000354 c. 0.0354 d. 354 e. -

Space and Planetary Environment Criteria Guidelines for Use in Space Vehicle Development, 1 9 8 2 Revision Volume 1

NASA Technicd Memorandum 8 2 4 7 8 Space and Planetary Environment Criteria Guidelines for Use in Space Vehicle Development, 1 9 8 2 Revision Volume 1 Robert E. Smith ar~dGeorge S. West, Compilers George C. Marshall Space Flight Center Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama National Aeronautics and Space Administration Sclentlfice and Technical lealormation 'Branch TABLE OF CONTENTS Page viii SECTIOP; 1. THE SUN ............................................ .......... 1.1 Introduction ....................... .. ............. ....a* 1.2 Brief Qualitative Description ............................. 1.3 Physical Properties .................................... .. 1.4 Solar Emanations - Descriptive .......................... 1.4.1 The Nature of the Sun's Output .................. 1.4.2 The Solar Cycle ................................... 1.4.3 Variation in the Sun's Output ................... .. 1.5 Solar Electromagnetic Radiation ........................... 1.5.1 Measurements of the Solar Constant ............... 1.5.2 Short-Term Fluctuations in the Solar Constant . .: . 1.5.3 The Solar Spectral Irradiance ..................... 1.6 Solar Plasma Emission .................................... 1.6.1 Properties of the Mean $olar Wind ................. 1.6.2 The Solar Wind and the Interplanetary Magnetic Field ............................................. 1.6.3 High-speed Streams ............................... 1.6.4 Coronal Transients ....................... .. .. .. ... 1.6.5 Spatial Variation of Solar Wind Properties ......... 1.6.6 Variation of the -

The Science Return from Venus Express the Science Return From

The Science Return from Venus Express Venus Express Science Håkan Svedhem & Olivier Witasse Research and Scientific Support Department, ESA Directorate of Scientific Programmes, ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands Dmitri V. Titov Max Planck Institute for Solar System Studies, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany (on leave from IKI, Moscow) ince the beginning of the space era, Venus has been an attractive target for Splanetary scientists. Our nearest planetary neighbour and, in size at least, the Earth’s twin sister, Venus was expected to be very similar to our planet. However, the first phase of Venus spacecraft exploration (1962-1985) discovered an entirely different, exotic world hidden behind a curtain of dense cloud. The earlier exploration of Venus included a set of Soviet orbiters and descent probes, the Veneras 4 to14, the US Pioneer Venus mission, the Soviet Vega balloons and the Venera 15, 16 and Magellan radar-mapping orbiters, the Galileo and Cassini flybys, and a variety of ground-based observations. But despite all of this exploration by more than 20 spacecraft, the so-called ‘morning star’ remains a mysterious world! Introduction All of these earlier studies of Venus have given us a basic knowledge of the conditions prevailing on the planet, but have generated many more questions than they have answered concerning its atmospheric composition, chemistry, structure, dynamics, surface-atmosphere interactions, atmospheric and geological evolution, and plasma environment. It is now high time that we proceed from the discovery phase to a thorough -

Hesperos: a Geophysical Mission to Venus

Hesperos: A geophysical mission to Venus Robert-Jan Koopmansa,∗, Agata Bia lekb, Anthony Donohoec, Mar´ıa Fern´andezJim´enezd, Barbara Frasle, Antonio Gurciullof, Andreas Kleinschneiderg, AnnaLosiak h, Thurid Manneli, I~nigoMu~nozElorzaj, Daniel Nilssonk, Marta Oliveiral, Paul Magnus Sørensen-Clarkm, Ryan Timoneyn, Iris van Zelsto aFOTEC Forschungs- und Technologietransfer GmbH, Wiener Neustadt, Austria bSpace Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland cMaynooth University, Department of Experimental Physics, Maynooth, Ireland dUniversidad Carlos III, Madrid, Spain eZentralanstalt f¨urMeteorologie und Geodynamik, Vienna, Austria fRoyal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden gDelft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands hInstitute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Science, Wroclaw, Poland iInstitute for Space Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences jHE Space Operations GmbH, Bremen, Germany kLule˚aUniversity of Technology, Lule˚a,Sweden lInstituto Superior T´ecnico, Lisbon, Portugal mUniversity of Oslo, Oslo, Norway nUniversity of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom oInstitute of Geophysics, ETH Z¨urich,Z¨urich,Switzerland Abstract The Hesperos mission proposed in this paper is a mission to Venus to in- vestigate the interior structure and the current level of activity. The main questions to be answered with this mission are whether Venus has an internal structure and composition similar to Earth and if Venus is still tectonically active. To do so the mission will consist of two elements: an orbiter to in- vestigate the interior and changes over longer periods of time and a balloon floating at an altitude between 40 and 60km~ to investigate the composition arXiv:1803.06652v1 [astro-ph.EP] 18 Mar 2018 of the atmosphere. The mission will start with the deployment of the balloon which will operate for about 25 days. -

15Th Meeting of the Venus Exploration and Analysis Group (VEXAG)

Program 15th Meeting of the Venus Exploration and Analysis Group (VEXAG) November 14–16, 2017 • Laurel, Maryland Sponsors Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Venus Exploration Analysis Group Program Committee Giada Arney University of Washington Martha Gilmore Wesleyan University Robert Grimm Southwest Research Institute Gary Hunter NASA Glenn Research Center Constantine Tsang Southwest Research Institute Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at https://www.lpi.usra.edu/vexag/meetings/vexag-15/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. B. and Author C. D. (2017) Title of abstract. In 15th Meeting of the Venus Exploration and Analysis Group (VEXAG), Abstract #XXXX. LPI Contribution No. 2061, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. Program Tuesday, November 14, 2017 NASA AND MISSION STUDY REPORTS 8:00 a.m. 8:00 a.m. Registration 8:15 a.m. Grimm R. * Welcome and Objectives of 15th VEXAG Meeting 8:30 a.m. Green J. * NASA Planetary Science Division and Responses to Previous VEXAG Findings 9:30 a.m. Nguyen Q. V. * Hunter G. W. NASA High Operating Temperature Technology Program Overview [#8046] NASA’s Planetary Science Division has begun the High Operating Temperature Technology (HOTTech) program to address Venus surface technology challenges by investing in new technology development. This presentation reviews this HOTTech program. 9:45 a.m. Gaier J. * NASA PICASSO and MatISSE Instrument-Development Programs 10:00 a.m. Coffee Break 10:30 a.m. Mercer C. * NASA Planetary Science Deep Space Smallsats 10:45 a.m. -

Composition and Chemistry of the Neutral Atmosphere of Venus Emmanuel Marcq, Franklin P

Composition and Chemistry of the Neutral Atmosphere of Venus Emmanuel Marcq, Franklin P. Mills, Christopher D. Parkinson, Ann Carine Vandaele To cite this version: Emmanuel Marcq, Franklin P. Mills, Christopher D. Parkinson, Ann Carine Vandaele. Composition and Chemistry of the Neutral Atmosphere of Venus. Space Science Reviews, Springer Verlag, 2018, 214, pp.article 10. 10.1007/s11214-017-0438-5. insu-01656562 HAL Id: insu-01656562 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-01656562 Submitted on 6 Dec 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Composition and Chemistry of the Neutral Atmosphere of Venus Emmanuel Marcq1 · Franklin P. Mills2 · Christopher D. Parkinson3 · Ann Carine Vandaele4 E. Marcq [email protected] 1 LATMOS/Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin, Guyancourt, France 2 Australian National University, Canberra, Australia 3 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA 4 Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy, Uccle, Belgium Abstract This paper deals with the composition and chemical processes occurring in the neutral atmosphere of Venus. Since the last synthesis, observers as well as modellers have emphasised the spatial and temporal variability of minor species, going beyond a static and uniform picture that may have prevailed in the past. -

Venus Exploration Themes

Venus Exploration Themes VEXAG Meeting #11 November 2013 VEXAG (Venus Exploration Analysis Group) is NASA’s community‐based forum that provides science and technical assessment of Venus exploration for the next few decades. VEXAG is chartered by NASA Headquarters Science Mission Directorate’s Planetary Science Division and reports its findings to both the Division and to the Planetary Science Subcommittee of NASA’s Advisory Council, which is open to all interested scientists and engineers, and regularly evaluates Venus exploration goals, objectives, and priorities on the basis of the widest possible community outreach. Front cover is a collage showing Venus at radar wavelength, the Magellan spacecraft, and artists’ concepts for a Venus Balloon, the Venus In‐Situ Explorer, and the Venus Mobile Explorer. (Collage prepared by Tibor Balint) Perspective view of Ishtar Terra, one of two main highland regions on Venus. The smaller of the two, Ishtar Terra, is located near the north pole and rises over 11 km above the mean surface level. Courtesy NASA/JPL–Caltech. VEXAG Charter. The Venus Exploration Analysis Group is NASA's community‐based forum designed to provide scientific input and technology development plans for planning and prioritizing the exploration of Venus over the next several decades. VEXAG is chartered by NASA's Solar System Exploration Division and reports its findings to NASA. Open to all interested scientists, VEXAG regularly evaluates Venus exploration goals, scientific objectives, investigations, and critical measurement requirements, including especially recommendations in the NRC Decadal Survey and the Solar System Exploration Strategic Roadmap. Venus Exploration Themes: November 2013 Prepared as an adjunct to the three VEXAG documents: Goals, Objectives and Investigations; Roadmap; as well as Technologies distributed at VEXAG Meeting #11 in November 2013. -

Design and Analysis of Optimal Operational Orbits Around Venus for the Envision Mission Proposal

Design and Analysis of Optimal Operational Orbits around Venus for the EnVision Mission Proposal Marta Rocha Rodrigues de Oliveira Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Aerospace Engineering Supervisors: Prof. Paulo Jorge Soares Gil Prof. Richard Ghail Examination Committee Chairperson: Filipe Szolnoky Ramos Pinto Cunha Supervisor: Paulo Jorge Soares Gil Member of the Committee: João Manuel Gonçalves de Sousa Oliveira November 2015 ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors Professor Paulo Gil from Instituto Superior Tecnico´ and Professor Richard Ghail from Imperial College London. Without their help, counsel, and generous transmission of knowledge, this thesis would not have been possible. I must also thank the EnVision team for the unique opportunity of working with such an exciting Venus project and contributing to an outstanding ESA proposal. Furthermore, I would like to express my appreciation to Dr. Edward Wright and to the NAIF team from JPL for the exceptional support provided. For the very welcomed inspiration, I must thank my friends, in particular the ISU community who encouraged me to pursue my work when I was reaching a breaking point. This thesis is dedicated to my parents and my sister, who give meaning and purpose to all my pursuits. iii iv Resumo Na explorac¸ao˜ espacial, as missoes˜ planetarias´ em orbita´ sao˜ essenciais para obter informac¸ao˜ so- bre os planetas como um todo, e ajudar a resolver questoes˜ cient´ıficas pendentes. Em particular, os planetas mais parecidos com a Terra temˆ sido um alvo privilegiado das principais agenciasˆ espaci- ais internacionais. EnVision e´ uma proposta de missao˜ que tem como objectivo justamente estudar um desses planetas.