Arxiv:2009.11826V3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

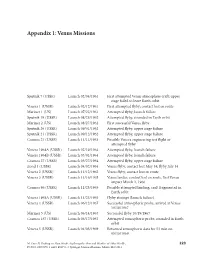

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

EDL – Lessons Learned and Recommendations

."#!(*"# 0 1(%"##" !)"#!(*"#* 0 1"!#"("#"#(-$" ."!##("""*#!#$*#( "" !#!#0 1%"#"! /!##"*!###"#" #"#!$#!##!("""-"!"##&!%%!%&# $!!# %"##"*!%#'##(#!"##"#!$$# /25-!&""$!)# %"##!""*&""#!$#$! !$# $##"##%#(# ! "#"-! *#"!,021 ""# !"$!+031 !" )!%+041 #!( !"!# #$!"+051 # #$! !%#-" $##"!#""#$#$! %"##"#!#(- IPPW Enabled International Collaborations in EDL – Lessons Learned and Recommendations: Ethiraj Venkatapathy1, Chief Technologist, Entry Systems and Technology Division, NASA ARC, 2 Ali Gülhan , Department Head, Supersonic and Hypersonic Technologies Department, DLR, Cologne, and Michelle Munk3, Principal Technologist, EDL, Space Technology Mission Directorate, NASA. 1 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA [email protected]. 2 Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. (DLR), German Aerospace Center, [email protected] 3 NASA Langley Research Center, Hampron, VA. [email protected] Abstract of the Proposed Talk: One of the goals of IPPW has been to bring about international collaboration. Establishing collaboration, especially in the area of EDL, can present numerous frustrating challenges. IPPW presents opportunities to present advances in various technology areas. It allows for opportunity for general discussion. Evaluating collaboration potential requires open dialogue as to the needs of the parties and what critical capabilities each party possesses. Understanding opportunities for collaboration as well as the rules and regulations that govern collaboration are essential. The authors of this proposed talk have explored and established collaboration in multiple areas of interest to IPPW community. The authors will present examples that illustrate the motivations for the partnership, our common goals, and the unique capabilities of each party. The first example involves earth entry of a large asteroid and break-up. NASA Ames is leading an effort for the agency to assess and estimate the threat posed by large asteroids under the Asteroid Threat Assessment Project (ATAP). -

Investigating Mineral Stability Under Venus Conditions: a Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies Erika Kohler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies Erika Kohler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Geochemistry Commons, Mineral Physics Commons, and the The unS and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Kohler, Erika, "Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1473. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1473 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Space and Planetary Sciences by Erika Kohler University of Oklahoma Bachelors of Science in Meteorology, 2010 May 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________ Dr. Claud H. Sandberg Lacy Dissertation Director Committee Co-Chair ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. Vincent Chevrier Dr. Larry Roe Committee Co-chair Committee Member ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. John Dixon Dr. Richard Ulrich Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Radar studies of the surface of Venus have identified regions with high radar reflectivity concentrated in the Venusian highlands: between 2.5 and 4.75 km above a planetary radius of 6051 km, though it varies with latitude. -

Sanjay Limaye US Lead-Investigator Ludmila Zasova Russian Lead-Investigator Steering Committee K

Answer to the Call for a Medium-size mission opportunity in ESA’s Science Programme for a launch in 2022 (Cosmic Vision 2015-2025) EuropEan VEnus ExplorEr An in-situ mission to Venus Eric chassEfièrE EVE Principal Investigator IDES, Univ. Paris-Sud Orsay & CNRS Universite Paris-Sud, Orsay colin Wilson Co-Principal Investigator Dept Atm. Ocean. Planet. Phys. Oxford University, Oxford Takeshi imamura Japanese Lead-Investigator sanjay Limaye US Lead-Investigator LudmiLa Zasova Russian Lead-Investigator Steering Committee K. Aplin (UK) S. Lebonnois (France) K. Baines (USA) J. Leitner (Austria) T. Balint (USA) S. Limaye (USA) J. Blamont (France) J. Lopez-Moreno (Spain) E. Chassefière(F rance) B. Marty (France) C. Cochrane (UK) M. Moreira (France) Cs. Ferencz (Hungary) S. Pogrebenko (The Neth.) F. Ferri (Italy) A. Rodin (Russia) M. Gerasimov (Russia) J. Whiteway (Canada) T. Imamura (Japan) C. Wilson (UK) O. Korablev (Russia) L. Zasova (Russia) Sanjay Limaye Ludmilla Zasova Eric Chassefière Takeshi Imamura Colin Wilson University of IKI IDES ISAS/JAXA University of Oxford Wisconsin-Madison Laboratory of Planetary Space Science and Spectroscopy Univ. Paris-Sud Orsay & Engineering Center Space Research Institute CNRS 3-1-1, Yoshinodai, 1225 West Dayton Street Russian Academy of Sciences Universite Paris-Sud, Bat. 504. Sagamihara Dept of Physics Madison, Wisconsin, Profsoyusnaya 84/32 91405 ORSAY Cedex Kanagawa 229-8510 Parks Road 53706, USA Moscow 117997, Russia FRANCE Japan Oxford OX1 3PU Tel +1 608 262 9541 Tel +7-495-333-3466 Tel 33 1 69 15 67 48 Tel +81-42-759-8179 Tel 44 (0)1-865-272-086 Fax +1 608 235 4302 Fax +7-495-333-4455 Fax 33 1 69 15 49 11 Fax +81-42-759-8575 Fax 44 (0)1-865-272-923 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] European Venus Explorer – Cosmic Vision 2015 – 2025 List of EVE Co-Investigators NAME AFFILIATION NAME AFFILIATION NAME AFFILIATION AUSTRIA Migliorini, A. -

18Th Meeting of the Venus Exploration Analysis Group (Vexag)

18TH MEETING OF THE VENUS EXPLORATION ANALYSIS GROUP (VEXAG) Program and Abstracts LPI Contribution No. 2356 18th Meeting of the Venus Exploration Analysis Group November 16–17, 2020 Institutional Support Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Convener Noam Izenberg Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory Darby Dyar Mount Holyoke College Science Organizing Committee Darby Dyar Planetary Science Institute, Mount Holyoke College Noam Izenberg JHU Applied Physics Laboratory Megan Andsell NASA Headquarters Natasha Johnson NASA Goddard Jennifer Jackson California Institute of Technology Jim Cutts Jet Propulsion Laboratory Tommy Thompson Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Compiled in 2020 by Meeting and Publication Services Lunar and Planetary Institute USRA Houston 3600 Bay Area Boulevard, Houston TX 77058-1113 This material is based upon work supported by NASA under Award No. 80NSSC20M0173. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this volume are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Lunar and Planetary Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under a cooperative agreement with the Science Mission Directorate of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. ISSN No. 0161-5297 Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/vexag2020/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. -

Space and Planetary Environment Criteria Guidelines for Use in Space Vehicle Development, 1 9 8 2 Revision Volume 1

NASA Technicd Memorandum 8 2 4 7 8 Space and Planetary Environment Criteria Guidelines for Use in Space Vehicle Development, 1 9 8 2 Revision Volume 1 Robert E. Smith ar~dGeorge S. West, Compilers George C. Marshall Space Flight Center Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama National Aeronautics and Space Administration Sclentlfice and Technical lealormation 'Branch TABLE OF CONTENTS Page viii SECTIOP; 1. THE SUN ............................................ .......... 1.1 Introduction ....................... .. ............. ....a* 1.2 Brief Qualitative Description ............................. 1.3 Physical Properties .................................... .. 1.4 Solar Emanations - Descriptive .......................... 1.4.1 The Nature of the Sun's Output .................. 1.4.2 The Solar Cycle ................................... 1.4.3 Variation in the Sun's Output ................... .. 1.5 Solar Electromagnetic Radiation ........................... 1.5.1 Measurements of the Solar Constant ............... 1.5.2 Short-Term Fluctuations in the Solar Constant . .: . 1.5.3 The Solar Spectral Irradiance ..................... 1.6 Solar Plasma Emission .................................... 1.6.1 Properties of the Mean $olar Wind ................. 1.6.2 The Solar Wind and the Interplanetary Magnetic Field ............................................. 1.6.3 High-speed Streams ............................... 1.6.4 Coronal Transients ....................... .. .. .. ... 1.6.5 Spatial Variation of Solar Wind Properties ......... 1.6.6 Variation of the -

Vexag/ Completed

Planetary Science Sub-committee Meeting 8 April 2010 http://www.lpi.usra.edu/vexag/ Completed: Upcoming: 8 April 2010 PSS Meeting: VEXAG Status Limaye - 2 • Venus Express is operating normally. ESA has approved extension through end of 2012. Orbit change from 24 hour period to 12 hour being planned which will enable spacecraft operations through ~ 2015. • JAXA’s Akatsuki (Venus Climate Orbiter) spacecraft is now at the launch site. Launch window opens May 18, 2010. Expected to arrive at Venus in December 2010 and observe Venus from a 172 degree eccentric, 30 hour orbit. 8 April 2010 PSS Meeting: VEXAG Status Limaye - 3 Future International Venus Exploration Efforts • European Venus Explorer, a balloon mission undergoing preliminary studies in Europe for a proposal to be developed for the next round of Cosmic Vision Program in ~ 2011. • Venera D is mission concept (Balloons, landers, orbiter) being studied in Russia for potential launch after 2016. Informal overtures being made to ISRO to promote potential interest in missions to Venus. A mission to Mars in 2013-2015 is under consideration by ISRO. ISRO appears interested in considering Venus as a future target 8 April 2010 PSS Meeting: VEXAG Status Limaye - 4 Status No missions to Venus have been selected so far for implementation in NASA’s Discovery, despite proposals deemed selectable The rich science questions about Venus, spanning from surface, interior, atmosphere, and ionosphere, will require many missions for answers. No large, multi-element mission to Venus is likely before 2020. Technology development, including precursor missions, is needed to enable many key missions for Venus. -

The Science Return from Venus Express the Science Return From

The Science Return from Venus Express Venus Express Science Håkan Svedhem & Olivier Witasse Research and Scientific Support Department, ESA Directorate of Scientific Programmes, ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands Dmitri V. Titov Max Planck Institute for Solar System Studies, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany (on leave from IKI, Moscow) ince the beginning of the space era, Venus has been an attractive target for Splanetary scientists. Our nearest planetary neighbour and, in size at least, the Earth’s twin sister, Venus was expected to be very similar to our planet. However, the first phase of Venus spacecraft exploration (1962-1985) discovered an entirely different, exotic world hidden behind a curtain of dense cloud. The earlier exploration of Venus included a set of Soviet orbiters and descent probes, the Veneras 4 to14, the US Pioneer Venus mission, the Soviet Vega balloons and the Venera 15, 16 and Magellan radar-mapping orbiters, the Galileo and Cassini flybys, and a variety of ground-based observations. But despite all of this exploration by more than 20 spacecraft, the so-called ‘morning star’ remains a mysterious world! Introduction All of these earlier studies of Venus have given us a basic knowledge of the conditions prevailing on the planet, but have generated many more questions than they have answered concerning its atmospheric composition, chemistry, structure, dynamics, surface-atmosphere interactions, atmospheric and geological evolution, and plasma environment. It is now high time that we proceed from the discovery phase to a thorough -

Hesperos: a Geophysical Mission to Venus

Hesperos: A geophysical mission to Venus Robert-Jan Koopmansa,∗, Agata Bia lekb, Anthony Donohoec, Mar´ıa Fern´andezJim´enezd, Barbara Frasle, Antonio Gurciullof, Andreas Kleinschneiderg, AnnaLosiak h, Thurid Manneli, I~nigoMu~nozElorzaj, Daniel Nilssonk, Marta Oliveiral, Paul Magnus Sørensen-Clarkm, Ryan Timoneyn, Iris van Zelsto aFOTEC Forschungs- und Technologietransfer GmbH, Wiener Neustadt, Austria bSpace Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland cMaynooth University, Department of Experimental Physics, Maynooth, Ireland dUniversidad Carlos III, Madrid, Spain eZentralanstalt f¨urMeteorologie und Geodynamik, Vienna, Austria fRoyal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden gDelft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands hInstitute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Science, Wroclaw, Poland iInstitute for Space Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences jHE Space Operations GmbH, Bremen, Germany kLule˚aUniversity of Technology, Lule˚a,Sweden lInstituto Superior T´ecnico, Lisbon, Portugal mUniversity of Oslo, Oslo, Norway nUniversity of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom oInstitute of Geophysics, ETH Z¨urich,Z¨urich,Switzerland Abstract The Hesperos mission proposed in this paper is a mission to Venus to in- vestigate the interior structure and the current level of activity. The main questions to be answered with this mission are whether Venus has an internal structure and composition similar to Earth and if Venus is still tectonically active. To do so the mission will consist of two elements: an orbiter to in- vestigate the interior and changes over longer periods of time and a balloon floating at an altitude between 40 and 60km~ to investigate the composition arXiv:1803.06652v1 [astro-ph.EP] 18 Mar 2018 of the atmosphere. The mission will start with the deployment of the balloon which will operate for about 25 days. -

COSMIC VISION 2015-2025 TECHNOLOGY PLAN Programme

COSMIC VISION 2015-2025 TECHNOLOGY PLAN Programme of Work 2008-2011 and related Procurement Plan SUMMARY The present document presents the currently proposed activities in the Basic Technology Programme (TRP), the Science Core Technology Programme (CTP), the General Support Technology Programme (GSTP) and suggested national initiatives supporting the implementation of the first slice of ESA’s Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 Plan. Page 2 Page 2 - Intentionally left blank Page 3 1. Background and Scope This document provides an update to the Cosmic Vision 1525 (CV1525) ESA Science Programme future missions technology preparation plan, first issued last year as ESA/IPC(2008)33, add1. This plan is submitted to the June 2009 SPC. The evolution of the CV1525 programme is taken into account, – essentially SPC recent decision to include Solar Orbiter as Medium (M) class mission and the outer planet Large (L) mission down-selection - the findings of the associated system study activities and the progress with the international coordination. The plan covers the period 2008-2011 for both the L/M missions under assessment and the future science mission themes. 2. Cosmic Vision Plan 2015-2025 2.1 Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 plan Evolution The Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 plan consists of a number of “Science Questions” to be addressed in the course of the 2015-2025 decade. The future space missions to be implemented to this purpose would result from competitive Announcements of Opportunity (AO hereafter) and following down selection processes. Three AOs were foreseen, defining the three “slices” of the plan. The down selection review and decision process is described in ESA/SPC(2009)3, rev.1. -

Venus L2/L3 White Paper Colin Wilson 23 May 2013

Venus L2/L3 White Paper Colin Wilson 23 May 2013 Venus: Key to understanding the evolution of terrestrial planets A response to ESA’s Call for White Papers for the Definition of Science Themes for L2/L3 Missions in the ESA Science Programme. ? Spokesperson: Colin Wilson Atmospheric, Oceanic and Planetary Physics, Clarendon Laboratory, University of Oxford, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Venus L2/L3 White Paper Colin Wilson 23 May 2013 Executive summary In this White Paper, we advocate L2/L3 science themes of understanding the diversity and evolution of habitable planets, and emphasize the importance of Venus to these science themes. Why are the terrestrial planets so different from each other? Venus should be the most Earth-like of all our planetary neighbours. Its size, bulk composition and distance from the Sun are very similar to those of the Earth. Its original atmosphere was probably similar to that of early Earth, with large atmospheric abundances of carbon dioxide and water. Furthermore, the young sun’s fainter output may have permitted a liquid water ocean on the surface. While on Earth a moderate climate ensued, Venus experienced runaway greenhouse warming, which led to its current hostile climate. How and why did it all go wrong for Venus? What lessons can we learn about the life story of terrestrial planets/exoplanets in general, whether in our solar system or in others? ESA’s Venus Express mission has proved tremendously successful, answering many questions about Earth’s sibling planet and establishing European leadership in Venus research. However, further understanding of Venus and its history requires several further lines of investigation. -

Atmospheric Planetary Probes And

SPECIAL ISSUE PAPER 1 Atmospheric planetary probes and balloons in the solar system A Coustenis1∗, D Atkinson2, T Balint3, P Beauchamp3, S Atreya4, J-P Lebreton5, J Lunine6, D Matson3,CErd5,KReh3, T R Spilker3, J Elliott3, J Hall3, and N Strange3 1LESIA, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, Meudon Cedex, France 2Department Electrical & Computer Engineering, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 4University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 5ESA/ESTEC, AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands 6Dipartment di Fisica, University degli Studi di Roma, Rome, Italy The manuscript was received on 28 January 2010 and was accepted after revision for publication on 5 November 2010. DOI: 10.1177/09544100JAERO802 Abstract: A primary motivation for in situ probe and balloon missions in the solar system is to progressively constrain models of its origin and evolution. Specifically, understanding the origin and evolution of multiple planetary atmospheres within our solar system would provide a basis for comparative studies that lead to a better understanding of the origin and evolution of our Q1 own solar system as well as extra-solar planetary systems. Hereafter, the authors discuss in situ exploration science drivers, mission architectures, and technologies associated with probes at Venus, the giant planets and Titan. Q2 Keywords: 1 INTRODUCTION provide significant design challenge, thus translating to high mission complexity, risk, and cost. Since the beginning of the space age in 1957, the This article focuses on the exploration of planetary United States, European countries, and the Soviet bodies with sizable atmospheres, using entry probes Union have sent dozens of spacecraft, including and aerial mobility systems, namely balloons.