Venus Exploration Themes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Space Impact of the Euro Crisis 50 Years After Mariner 2: Exploration at a Crossroads

0827_SPN_DOM_00_019_00 (READ ONLY) 8/24/2012 11:39 AM Page 19 www.spacenews.com SPACENEWS 19 August27, 2012 TheSpaceImpact of the Euro Crisis < ROBBIN LAIRD and HARALD MALMGREN > he European sovereign debt crisis Europe will now be challenged in the ing to hide the reality of European bank of the savings of millions of European is not simply abump in historical form of rollbacks of the many inter- weaknesses. The main reason is that eu- citizens. Tprogress; it is the end of aperiod twined strands of integration, fraying rozone economies are far more bank- European leaders are also attempt- of historyand acritical point in Euro- what has been an intricate but incom- dependent than economies like those in ing to initiate amore comprehensive fis- pean and global transition in the 21st plete tapestry. It is questionable whether the United States or United Kingdom, cal union, with new decision-making century. Europe will be able to prevent stalling of where substantial nonbank financing al- mechanisms that transfer sovereignty in The confluence of several trend lines the integration process in the face of ternatives exist for the corporate sector. parallel with the new banking union. We — the unification of Germany,the end widening gaps among the interests of In the eurozone, banks are the fi- do not believe that any of the eurozone of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the each nation and even within each nation. nancial markets; in the U.S., banks are governments are ready for such apoliti- Berlin Wall, the expansion of NATO, Since the birth of the euro, the but one segment of amultifaceted fi- cal transition in which citizens in each the expansion of the European Union French and Germans were in the lead in nancial market. -

MARS an Overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera Science

MARS MARS INFORMATICS The International Journal of Mars Science and Exploration Open Access Journals Science An overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera science investigation Michael C. Malin1, Kenneth S. Edgett1, Bruce A. Cantor1, Michael A. Caplinger1, G. Edward Danielson2, Elsa H. Jensen1, Michael A. Ravine1, Jennifer L. Sandoval1, and Kimberley D. Supulver1 1Malin Space Science Systems, P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, CA, 92191-0148, USA; 2Deceased, 10 December 2005 Citation: Mars 5, 1-60, 2010; doi:10.1555/mars.2010.0001 History: Submitted: August 5, 2009; Reviewed: October 18, 2009; Accepted: November 15, 2009; Published: January 6, 2010 Editor: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University Reviewers: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University; R. Aileen Yingst, University of Wisconsin Green Bay Open Access: Copyright 2010 Malin Space Science Systems. This is an open-access paper distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: NASA selected the Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) investigation in 1986 for the Mars Observer mission. The MOC consisted of three elements which shared a common package: a narrow angle camera designed to obtain images with a spatial resolution as high as 1.4 m per pixel from orbit, and two wide angle cameras (one with a red filter, the other blue) for daily global imaging to observe meteorological events, geodesy, and provide context for the narrow angle images. Following the loss of Mars Observer in August 1993, a second MOC was built from flight spare hardware and launched aboard Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) in November 1996. -

A Comparison Study on Thermal Control Techniques for a Nanosatellite Carrying Infrared Science Instrument

ICES-2020-15 A comparison study on thermal control techniques for a nanosatellite carrying infrared science instrument Shanmugasundaram Selvadurai1, Amal Chandran2, Sunil C Joshi3 and Teo Hang Tong Edwin 4 Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 639798 David Valentini5 Thales Alenia Space, Cannes, 06150, France Friedhelm Olschewski6 University of Wuppertal, 42119 Wuppertal, Germany Based on current technological advancements and forecasts, nanosatellites will be used for both scientific and defense applications leveraging advantages on both development cost and development lifecycle. As nanosatellites become more capable, there is an increase in demand for high power applications which makes the missions complex from implementing a proper thermal control system (TCS) to dissipate the huge waste heat generated. One of the applications for nanosatellites is advanced infrared imaging for both scientific and military applications. ARCADE (Atmospheric coupling and Dynamics Explorer), a 27U satellite is being developed by Satellite Research Centre (SaRC) at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) for scientific objectives. The main payload AtmoLITE needs a detector cool down at -30°C and to meet this requirement, an appropriate classical TCS is chosen and described in this paper. Nanosatellites carrying infrared, cryogenic or other scientific instruments that need active cooling, should be equipped with a proper TCS within the highly constrained available volume. Another objective of this study is to compare the existing TCS for nanosatellites and adopt a suitable and efficient TCS for a scientific nanosatellite mission carrying a generic science instrument that needs an active cooling of up to 95K. TCS using Heat pipes (HP), single-phase mechanically pumped fluid loop (SMPFL), and two-phase mechanically pumped fluid loop systems (2ΦMPFL) have been extensively used only by larger satellites. -

CRATER MORPHOMETRY on VENUS. C. G. Cochrane, Imperial College, London ([email protected])

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIV (2003) 1173.pdf CRATER MORPHOMETRY ON VENUS. C. G. Cochrane, Imperial College, London ([email protected]). Introduction: Most impact craters on Venus are propagating east and north/south. Can be minimised if pristine, and provide probably the best available ana- framelets have good texture on the left-hand side. logs for craters on Earth soon after impact; hence the Prominence extension – features extend down value of measuring their 3-D shape to known accuracy. range into a ridge, eg central peak linked to the rim. The USGS list 967 craters: from the largest, Mead at Probably due to radar shadowing differences, these are 270 km diameter, to the smallest, unnamed at 1.3 km. easily recognised and avoided during analysis. Initially, research focussed on the larger craters. Araration (from Latin: Arare to plough) consists of Schaber et al [1] (11 craters >50 km) and Ivanov et al parallel furrows some 50 pixels apart, oriented north- [2] (31 craters >70 km) took crater depth from Magel- south, and at least tens of metres deep. Fig 2, a lan altimetry. Sharpton [3] (94 craters >18 km) used floor-offsets in Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) F- MIDR pairs, as did Herrick & Phillips [4]. They list many parameters but not depth for 891 craters. The LPI database1 now numbers 941. Herrick & Sharpton [5] made Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) of all cra- ters at least partially imaged twice down to 12 km, and 20 smaller craters down to 3.6 km. Using FMAP im- ages and the Magellan Stereo Toolkit (MST) v.1, they automated matches every 900m but then manually ed- ited the resultant data. -

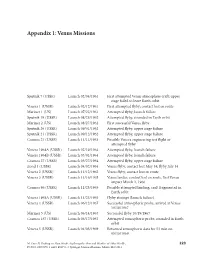

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization Clayton Knappenberger Depauw University

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2015 An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization Clayton Knappenberger DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Economics Commons, and the The unS and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Knappenberger, Clayton, "An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization" (2015). Student research. Paper 28. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Economic Analysis of Mars Exploration and Colonization Clayton Knappenberger 2015 Sponsored by: Dr. Villinski Committee: Dr. Barreto and Dr. Brown Contents I. Why colonize Mars? ............................................................................................................................ 2 II. Can We Colonize Mars? .................................................................................................................... 11 III. What would it look like? ............................................................................................................... 16 A. National Program ......................................................................................................................... -

Glossary of Acronyms and Definitions

CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2018 CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2019 1 Glossary of Acronyms and Definitions A A/D Analog-to-Digital AACS Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem AAN Automatic Alarm Notification AB Approved By ABS timed Absolute Timed AC Acoustics AC Alternating Current ACC Accelerometer ACCE Accelerometer Electronics ACCH Accelerometer Head ACE Aerospace Communications & Information Expertise ACE Aerospace Control Environment ACE Air Coordination Element ACE Attitude Control Electronics ACI Accelerometer Interface ACME Antenna Calibration and Measurement Equipment ACP Aerosol Collector Pyrolyzer ACS Attitude Control Subsystem ACT Actuator ACT Automated Command Tracker ACTS Advanced Communications Technology Satellite AD Applicable Document ADAS AWVR Data Acquisition Software ADC Analog-to-Digital Converter ADP Automatic Data Processing AE Activation Energy AEB Agência Espacial Brasileira (Brazilian Space Agency) AF Air Force AFC AACS Flight Computer AFETR Air Force Eastern Test Range AFETRM Air Force Eastern Test Range Manual 2 CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2019 AFS Atomic Frequency Standard AFT Abbreviated Functional Test AFT Allowable Flight Temperature AFS Andrew File System AGC Automatic Gain Control AGU American Geophysical Union AHSE Assembly, Handling, & Support Equipment AIT Assembly, Integration & Test AIV Assembly, Integration & Verification AKR Auroral Kilometric Radiation AL Agreement Letter AL Aluminum AL Anomalously Large ALAP As Low As Practical ALARA As Low As Reasonably Achievable ALB Automated Link -

Educator's Guide

EDUCATOR’S GUIDE ABOUT THE FILM Dear Educator, “ROVING MARS”is an exciting adventure that This movie details the development of Spirit and follows the journey of NASA’s Mars Exploration Opportunity from their assembly through their Rovers through the eyes of scientists and engineers fantastic discoveries, discoveries that have set the at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Steve Squyres, pace for a whole new era of Mars exploration: from the lead science investigator from Cornell University. the search for habitats to the search for past or present Their collective dream of Mars exploration came life… and maybe even to human exploration one day. true when two rovers landed on Mars and began Having lasted many times longer than their original their scientific quest to understand whether Mars plan of 90 Martian days (sols), Spirit and Opportunity ever could have been a habitat for life. have confirmed that water persisted on Mars, and Since the 1960s, when humans began sending the that a Martian habitat for life is a possibility. While first tentative interplanetary probes out into the solar they continue their studies, what lies ahead are system, two-thirds of all missions to Mars have NASA missions that not only “follow the water” on failed. The technical challenges are tremendous: Mars, but also “follow the carbon,” a building block building robots that can withstand the tremendous of life. In the next decade, precision landers and shaking of launch; six months in the deep cold of rovers may even search for evidence of life itself, space; a hurtling descent through the atmosphere either signs of past microbial life in the rock record (going from 10,000 miles per hour to 0 in only six or signs of past or present life where reserves of minutes!); bouncing as high as a three-story building water ice lie beneath the Martian surface today. -

Investigating Mineral Stability Under Venus Conditions: a Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies Erika Kohler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies Erika Kohler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Geochemistry Commons, Mineral Physics Commons, and the The unS and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Kohler, Erika, "Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1473. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1473 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Space and Planetary Sciences by Erika Kohler University of Oklahoma Bachelors of Science in Meteorology, 2010 May 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________ Dr. Claud H. Sandberg Lacy Dissertation Director Committee Co-Chair ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. Vincent Chevrier Dr. Larry Roe Committee Co-chair Committee Member ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. John Dixon Dr. Richard Ulrich Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Radar studies of the surface of Venus have identified regions with high radar reflectivity concentrated in the Venusian highlands: between 2.5 and 4.75 km above a planetary radius of 6051 km, though it varies with latitude. -

Climate Histories of Mars and Venus, and the Habitability of Planets

CLIMATE HISTORIES OF MARS AND VENUS, AND THE HABITABILITY OF PLANETS In the temporal sequence that Part III of the book has ¡NTRODUCT¡ON 15.1 been following, we stand near the end of the Archean eon. Earth at the close of the Archean,2.5 billion years ago, By this point in time, the evolution of Venus and its atmo- was a world in which life had arisen and plate tectonics sphere almost certainly had diverged from that of Earth, dominated, the evolution of the crust and the recycling of and Mars was on its way to being a cold, dry world, if volatiles. Yet oxygen (Oz) still was not prevalent in the it had not already become one. This is the appropriate atmosphere, which was richer in COz than at present. In moment in geologic time, then, to consider how Earth's this last respect, Earth's atmosphere was somewhat like neighboring planets diverged so greatly in climate, and to that of its neighbors, Mars and Venus, which today retain ponder the implications for habitable planets throughout this more primitive kind of atmosphere. the cosmos. In the following chapter, we consider why Speculations on the nature of Mars and Venus were, Earth became dominated by plate tectonics, but Venus prior to the space program, heavily influenced by Earth- and Mars did not. Understanding this is part of the key centered biases and the poor quality of telescopic observa- to understanding Earth's clement climate as discussed in tions (figure 15.1). Thirty years of U.S. and Soviet robotic chapter 1.4. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas.