Irreparable Damage: Violence, Ownership, and Voice in an Indian Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking Offense: Censorship and the Constitution of Democratic Politics in India

SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ameya Shivdas Balsekar August 2009 © 2009 Ameya Shivdas Balsekar SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA Ameya Shivdas Balsekar, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Commentators have frequently suggested that India is going through an “age of intolerance” as writers, artists, filmmakers, scholars and journalists among others have been targeted by institutions of the state as well as political parties and interest groups for hurting the sentiments of some section of Indian society. However, this age of intolerance has coincided with a period that has also been characterized by the “deepening” of Indian democracy, as previously subordinated groups have begun to participate more actively and substantively in democratic politics. This project is an attempt to understand the reasons for the persistence of illiberalism in Indian politics, particularly as manifest in censorship practices. It argues that one of the reasons why censorship has persisted in India is that having the “right to censor” has come be established in the Indian constitutional order’s negotiation of multiculturalism as a symbol of a cultural group’s substantive political empowerment. This feature of the Indian constitutional order has made the strategy of “seeking offense” readily available to India’s politicians, who understand it to be an efficacious way to discredit their competitors’ claims of group representativeness within the context of democratic identity politics. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

The 33Rd Annual Conference on South Asia (2004) Paper Abstracts

Single Paper and Individual Panel Abstracts 33rd Annual Conference on South Asia October 15-17, 2004 Note: Abstracts exceeding the 150-word limit were abbreviated and marked with an ellipsis. A. Rizvi, S. Mubbashir, University of Texas at Austin Refashioning Community: The Role of Violence in Redefining Political Society in Pakistan The history of sectarian conflict in Muslim communities in Pakistan goes back to the early days of national independence. The growing presence of extremist Sunni and Shi’a sectarian groups who are advocating for an Islamist State fashioned around their interpretation of Islam has resulted in an escalating wave of violence in the form of targeted killings of activists, religious clerics, Shi’a doctors, professionals and the most recent trend of suicide attacks targeting ordinary civilians. This paper will focus on the rise of sectarian tensions in Pakistan in relation to the changing character of Pakistani State in the Neo-Liberal era. Some of the questions that will be addressed are: What kinds of sectarian subjectivities are being shaped by the migration to the urban and peri-urban centers of Pakistan? What are the ways in which socio-economic grievances are reconfigured in sectarian terms? What are the ways in which violence shapes or politicizes … Adarkar, Aditya, Montclair State University Reflecting in Grief: Yudhishthira, Karna, and the Construction of Character This paper examines the construction of character in the "Mahabharata" through crystalline parallels and mirrorings (described by Ramanujan 1991). Taking Yudhishthira and Karna as an example, we learn much about Karna from the parallel between Karna's dharmic tests and Yudhishthira's on the way to heaven; and several aspects of Yudhishthira's personality (his blinding hatred, his adherence to his worldview) come to the fore in the context of his hatred of and grief over Karna. -

Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons @ Butler University Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 19 Article 5 2006 Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Recommended Citation Sathaye, Adheesh (2006) "Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute," Journal of Hindu- Christian Studies: Vol. 19, Article 5. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1360 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Sathaye: Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhankarkar Institute Censorship and Censureship: Insiders, Outsiders, and the Attack on Bhandarkar Institute Adheesh Sathaye University of British Columbia ON January 5, 2004, the Bhandarkar Institute, a prominent group of Maharashtrian historians large Sanskrit manuscript library in Pune, was sent a letter to OUP calling for its withdrawal. vandalized because of its involvement in James Apologetically, OUP pulled it from Indian Laine's controversial study of the Maharashtrian shelves on November 21,2003, but this did little king Shivaji. While most of the manuscripts to quell the outrage arising from one paragraph escaped damage, less fortunate was the in Laine's book deemed slanderous to Shivaji academic project of South Asian studies, which and his mother Jijabai: now faces sorpe serious questions. -

Molecular Insight Into the Genesis of Ranked Caste Populations Of

This information has not been peer-reviewed. Responsibility for the findings rests solely with the author(s). comment Deposited research article Molecular insight into the genesis of ranked caste populations of western India based upon polymorphisms across non-recombinant and recombinant regions in genome Sonali Gaikwad1 and VK Kashyap1,2* reviews Addresses: 1National DNA Analysis Center, Central Forensic Science Laboratory, Kolkata -700014, India. 2National Institute of Biologicals, Noida-201307, India. Correspondence: VK Kasyap. E-mail: [email protected] reports Posted: 19 July 2005 Received: 18 July 2005 Genome Biology 2005, 6:P10 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be This is the first version of this article to be made available publicly and no found online at http://genomebiology.com/2005/6/8/P10 other version is available at present. © 2005 BioMed Central Ltd deposited research refereed research .deposited research AS A SERVICE TO THE RESEARCH COMMUNITY, GENOME BIOLOGY PROVIDES A 'PREPRINT' DEPOSITORY TO WHICH ANY ORIGINAL RESEARCH CAN BE SUBMITTED AND WHICH ALL INDIVIDUALS CAN ACCESS interactions FREE OF CHARGE. ANY ARTICLE CAN BE SUBMITTED BY AUTHORS, WHO HAVE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ARTICLE'S CONTENT. THE ONLY SCREENING IS TO ENSURE RELEVANCE OF THE PREPRINT TO GENOME BIOLOGY'S SCOPE AND TO AVOID ABUSIVE, LIBELLOUS OR INDECENT ARTICLES. ARTICLES IN THIS SECTION OF THE JOURNAL HAVE NOT BEEN PEER-REVIEWED. EACH PREPRINT HAS A PERMANENT URL, BY WHICH IT CAN BE CITED. RESEARCH SUBMITTED TO THE PREPRINT DEPOSITORY MAY BE SIMULTANEOUSLY OR SUBSEQUENTLY SUBMITTED TO information GENOME BIOLOGY OR ANY OTHER PUBLICATION FOR PEER REVIEW; THE ONLY REQUIREMENT IS AN EXPLICIT CITATION OF, AND LINK TO, THE PREPRINT IN ANY VERSION OF THE ARTICLE THAT IS EVENTUALLY PUBLISHED. -

Political Economy of a Dominant Caste

Draft Political Economy of a Dominant Caste Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar* This paper is an attempt to investigate the multiple crises facing the Maratha community of Maharashtra. A dominant, intermediate peasantry caste that assumed control of the state’s political apparatus in the fifties, the Marathas ordinarily resided politically within the Congress fold and thus facilitated the continued domination of the Congress party within the state. However, Maratha politics has been in flux over the past two decades or so. At the formal level, this dominant community has somehow managed to retain power in the electoral arena (Palshikar- Birmal, 2003)—though it may be about to lose it. And yet, at the more intricate levels of political competition, the long surviving, complex patterns of Maratha dominance stand challenged in several ways. One, the challenge is of loss of Maratha hegemony and consequent loss of leadership of the non-Maratha backward communities, the OBCs. The other challenge pertains to the inability of different factions of Marathas to negotiate peace and ensure their combined domination through power sharing. And the third was the internal crisis of disconnect between political elite and the Maratha community which further contribute to the loss of hegemony. Various consequences emerged from these crises. One was simply the dispersal of the Maratha elite across different parties. The other was the increased competitiveness of politics in the state and the decline of not only the Congress system, but of the Congress party in Maharashtra. The third was a growing chasm within the community between the neo-rich and the newly impoverished. -

Vijaydurg ( Location on Map )

Vijaydurga The sleepy village boasts of a seemingly impregnable, pre Shivaji period fort that, maritime history says, was the scene of many a bloody battle. It has been attacked from the sea by the British to take it over from its Indian occupants. A dilapidated board at the entrance of the fort tells you its history. Some of the board is readable whilst the rest is guesswork since the paint has peeled off. Once upon a time the steamer from Bombay to Goa used to halt at the jetty near the entrance to the fort. Now the catamaran whizzes past oblivious of the fort, the town and the beach. Incidentally the one of the best views of the fort is from this jetty. The fort stretches out in to the sea and a walk inside its precincts is worthwhile. When I was there last, the organisers of the McDowell Bombay – Goa Regatta had established a staging post inside the fort and there was quite a bit of revelry. Otherwise no one really bothers to come here. The locals inform us that Mr Vijay Mallya, the liquor baron, boss of United Breweries that owns the McDowell Brand, has bought over a 100 acres of land in the area just north of here with a view to building a resort some time in the future. Gives you an indication of the potential of the place. Vijaydurg’s beach is quite hidden from view and is not obvious to the casual visitor. Ask for the small bus terminus just before you get to the fort and the road ends. -

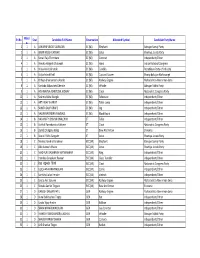

Sr.No.Ward No Seat Candidate Full Name Reservation Allocated

Sr.No. Ward Seat Candidate Full Name Reservation Allocated Symbol Candidate PartyName No 1 1 A ASHWINI VINOD VAIRAGAR SC (W) Elephant Bahujan Samaj Party 2 1 A KIRAN NILESH JATHAR SC (W) Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 3 1 A Sonali Raju Thombare SC (W) Coconut Independent/Other 4 1 A Renuka Hulgesh Chalwadi SC (W) Hand Indian National Congress 5 1 A Vidya Anil Lokhande SC (W) Candles Republican Party of India (A) 6 1 A Vidya Ashok Patil SC (W) Cup and Saucer Bharip Bahujan Mahasangh 7 1 A Chhaya Bhairavnath Ukarde SC (W) Railway Engine Maharashtra Navnirman Sena 8 1 A Kantabai Balasaheb Dhende SC (W) Whistle Bahujan Mukti Party 9 1 A AISHWARYA ASHUTOSH JADHAV SC (W) Clock Nationalist Congress Party 10 1 A Sushma Rahul Bengle SC (W) Television Independent/Other 11 1 A ARTI VIJAY KHARAT SC (W) Table Lamp Independent/Other 12 1 A SUNITA DILIP ORAPE SC (W) Jug Independent/Other 13 1 A NALINI RAJENDRA KAMBALE SC (W) Black Board Independent/Other 14 1 B NAVANATH SHIVAJI BHALCHIM ST Table Independent/Other 15 1 B Vithhal Ramchandra Kothere ST Clock Nationalist Congress Party 16 1 B Dunda Dongaru Kolap ST Bow And Arrow Shivsena 17 1 B Maruti Palhu Sangade ST Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 18 1 C Menka Jitendra Karalekar BCC (W) Elephant Bahujan Samaj Party 19 1 C Alka Avinash Khade BCC (W) Lotus Bhartiya Janata Party 20 1 C MADHURI DASHRATH MATWANKAR BCC (W) Ring Independent/Other 21 1 C Hemlata Suryakant Pawaar BCC (W) Glass Tumbler Independent/Other 22 1 C रेखा चंकांत टंगरे BCC (W) Clock Nationalist Congress Party 23 1 C GULSHAN KARIM MULANI BCC (W) -

Defining Goan Identity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 1-12-2006 Defining Goan Identity Donna J. Young Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Young, Donna J., "Defining Goan Identity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEFINING GOAN IDENTITY: A LITERARY APPROACH by DONNA J. YOUNG Under the Direction of David McCreery ABSTRACT This is an analysis of Goan identity issues in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries using unconventional sources such as novels, short stories, plays, pamphlets, periodical articles, and internet newspapers. The importance of using literature in this analysis is to present how Goans perceive themselves rather than how the government, the tourist industry, or tourists perceive them. Also included is a discussion of post-colonial issues and how they define Goan identity. Chapters include “Goan Identity: A Concept in Transition,” “Goan Identity: Defined by Language,” and “Goan Identity: The Ancestral Home and Expatriates.” The conclusion is that by making Konkani the official state language, Goans have developed a dual Goan/Indian identity. In addition, as the Goan Diaspora becomes more widespread, Goans continue to define themselves with the concept of building or returning to the ancestral home. INDEX WORDS: Goa, India, Goan identity, Goan Literature, Post-colonialism, Identity issues, Goa History, Portuguese Asia, Official languages, Konkani, Diaspora, The ancestral home, Expatriates DEFINING GOAN IDENTITY: A LITERARY APPROACH by DONNA J. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime the State of Minorities

100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities 100 Days Under the New Regime The State of Minorities A Report Edited by John Dayal ISBN: 978-81-88833-35-1 Suggested Contribution : Rs 100 Published by Anhad INDIA HAS NO PLACE FOR HATE AND NEEDS NOT A TEN-YEAR MORATORIUM BUT AN END TO COMMUNAL AND TARGETTED VIOLENCE AGAINST RELIGIOUS MINORITIES A report on the ground situation since the results of the General Elections were announced on16th May 2014 NEW DELHI, September 27th, 2014 The Prime Minister, Mr. Narendra Modi, led by Bharatiya Janata Party to a resounding victory in the general elections of 2014, riding a wave generated by his promise of “development” and assisted by a remarkable mass mobilization in one of the most politically surcharged electoral campaigns in the history of Independent India. When the results were announced on 16th May 2014, the BJP had won 280 of the 542 seats, with no party getting even the statutory 10 per cent of the seats to claim the position of Leader of the Opposition. The days, weeks and months since the historic victory, and his assuming ofice on 26th May 2014 as the 14th Prime Minister of India, have seen the rising pitch of a crescendo of hate speech against Muslims and Christians. Their identity derided,their patriotism scoffed at, their citizenship questioned, their faith mocked. The environment has degenerated into one of coercion, divisiveness, and suspicion. This has percolated to the small towns and villages or rural India, severing bonds forged in a dialogue of life over the centuries, shattering the harmony build around the messages of peace and brotherhood given us by the Suis and the men and women who led the Freedom Struggle under Mahatma Gandhi. -

Rise of the Marathas1/ Rakesh Kumar

E- Content/ Medieval India/ B.A.II(H) Rise of the Marathas1/ Rakesh kumar/ SMD College, Punpun. RISE OF THE MARATHAS The rise of the Marathas in India is an important chapter of Medieval Indian history. The emergence of Marathas as a political power had a number of consequences. It shows us the possibilities of the rise of a Hindu power in Modern India as enumerated in the HINDU PAD PADSHAHI of Baji Rao I. a possibility that was cut short by the English during Anglo- Maratha wars. As the chapter on the Marathas unfold, we discuss here, in this e – content, some of the underlying causes which led to the rise of the Maratha power in India. This is first of the series of lectures on the topic – Rise of the Marathas. GEOGRAPHICAL REGION: The early rise of the Marathas mostly comprised of the regions specified below. The region specified in this unfolding of events are western coastal areas of Konkan, Khandesh, Berar, Nagpur, areas of the south and some areas of the Nizam. This whole area was known as Marathwada in medieval times, according to historian Bhandarkar, an expert in the history of the Marathas. The people collectively known as the Marathas comprised of the Rathis, Rashtriks and Rathiks, who occupied these areas. In due course of time especially 17th century, they were able to organize themselves into a cohesive force whose 1 sword and diplomacy conquered and held sway over major parts of India in the Deccan and north as well. CAUSES OF THE RISE OF THE MARATHAS: Historian Grant Duff opines that the Marathas came out of the Sahayadri mountains like wild fire.