Japanese - American Relations, 1941: a Preface to Pearl Harbor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War TACHIKAWA Kyoichi Abstract Why does the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war occur? What are the fundamental causes of this problem? In this article, the author looks at the principal examples of abuse inflicted on European and American prisoners by military and civilian personnel of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy during the Pacific War to analyze the causes of abusive treatment of prisoners of war. In doing so, the author does not stop at simply attributing the causes to the perpetrators or to the prevailing condi- tions at the time, such as Japan’s deteriorating position in the war, but delves deeper into the issue of the abuse of prisoners of war as what he sees as a pathology that can occur at any time in military organizations. With this understanding, he attempts to examine the phenomenon from organizational and systemic viewpoints as well as from psychological and leadership perspectives. Introduction With the establishment of the Law Concerning the Treatment of Prisoners in the Event of Military Attacks or Imminent Ones (Law No. 117, 2004) on June 14, 2004, somewhat stringent procedures were finally established in Japan for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in the context of a system infrastructure. Yet a look at the world today shows that abusive treatment of prisoners of war persists. Indeed, the heinous abuse which took place at the former Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War is still fresh in our memories. -

Mystery of Tojo's Remains Solved

2A| SATURDAY, JUNE 19, 2021| TIMES RECORD NEWS Mystery of Tojo’s remains solved Secret mission scattered Luther Frierson wrote: “I certify that I received the remains, supervised cre- war criminal’s ashes mation, and personally scattered the ashes of the following executed war Mari Yamaguchi criminals at sea from an Eighth Army li- ASSOCIATED PRESS aison plane.” The entire operation was tense, with TOKYO – Until recently, the location U.S. officials extremely careful about of executed wartime Japanese Prime not leaving a single speck of ashes be- Minister Hideki Tojo’s remains was one hind, apparently to prevent them from of World War II’s biggest mysteries in being stolen by admiring ultra-nation- the nation he once led. alists, Takazawa said. Now, a Japanese university professor “In addition to their attempt to pre- revealed declassified U.S. military doc- vent the remains from being glorified, I uments that appear to hold the answer. think the U.S. military was adamant The documents show the cremated about not letting the remains return to ashes of Tojo, one of the masterminds of Japanese territory … as an ultimate hu- the Pearl Harbor attack, were scattered miliation,” Takazawa said. from a U.S. Army aircraft over the Pacif- The documents state that when the ic Ocean about 30 miles east of Yokoha- cremation was completed, the ovens ma, Japan’s second-largest city, south were “cleared of the remains in their en- of Tokyo. Former Japanese Prime Minister and military leader Hideki Tojo answers “not tirety.” It was a tension-filled, highly secre- guilty” during a war crimes trial in Tokyo in November 1948. -

Trianon 1920–2020 Some Aspects of the Hungarian Peace Treaty of 1920

Trianon 1920–2020 Some Aspects of the Hungarian Peace Treaty of 1920 TRIANON 1920–2020 SOME ASPECTS OF THE HUNGARIAN PEACE TREATY OF 1920 Edited by Róbert Barta – Róbert Kerepeszki – Krzysztof Kania in co-operation with Ádám Novák Debrecen, 2021 Published by The Debreceni Universitas Nonprofit Közhasznú Kft. and the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of History Refereed by Levente Püski Proofs read by Máté Barta Desktop editing, layout and cover design by Zoltán Véber Járom Kulturális Egyesület A könyv megjelenését a Nemzeti Kulturális Alap támomgatta. The publish of the book is supported by The National Cultural Fund of Hungary ISBN 978-963-490-129-9 © University of Debrecen, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of History, 2021 © Debreceni Universitas Nonprofit Közhasznú Kft., 2021 © The Authors, 2021 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Printed by Printart-Press Kft., Debrecen Managing Director: Balázs Szabó Cover design: A contemporary map of Europe after the Great War CONTENTS Foreword and Acknowledgements (RÓBERT BARTA) ..................................7 TRIANON AND THE POST WWI INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS MANFRED JATZLAUK, Deutschland und der Versailler Friedensvertrag von 1919 .......................................................................................................13 -

The Pacific War Crimes Trials: the Importance of the "Small Fry" Vs. the "Big Fish"

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Summer 2012 The aP cific aW r Crimes Trials: The mpI ortance of the "Small Fry" vs. the "Big Fish" Lisa Kelly Pennington Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pennington, Lisa K.. "The aP cific aW r Crimes Trials: The mporI tance of the "Small Fry" vs. the "Big Fish"" (2012). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/rree-9829 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PACIFIC WAR CRIMES TRIALS: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE "SMALL FRY" VS. THE "BIG FISH by Lisa Kelly Pennington B.A. May 2005, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2012 Approved by: Maura Hametz (Director) Timothy Orr (Member) UMI Number: 1520410 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

A Bridge Across the Pacific: a Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 1-7-2016 A Bridge Across the Pacific: A Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East Michael Todd Gagle Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Gagle, Michael Todd, "A Bridge Across the Pacific: A Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East" (2016). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2655. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2651 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Bridge Across the Pacific A Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East in the 1930s by Michael Todd Gagle A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Kenneth Ruoff, Chair Desmond Cheung David Johnson Jon Holt Portland State University 2015 © 2015 Michael Todd Gagle Abstract After Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, both Japan and China sought the support of America. There has been a historical assumption that, starting with the hostilities in 1931, the Japanese were maligned in American public opinion. Consequently, the assumption has been made that Americans supported the Chinese without reserve during their conflict with Japan in the 1930s. -

In 1912 Emperor Meiji Died, and the Era of the Ruling Clique of Elder Statesmen (Genro) Was About to End

In 1912 emperor Meiji died, and the era of the ruling clique of elder statesmen (genro) was about to end. During the era of the weak Emperor Taisho (1912-26), the political power shifted from the oligarchic clique (genro) to the parliament and the democratic parties. In the First World War, Japan joined the Allied powers, but played only a minor role in fighting German colonial forces in East Asia. On August 23, 1914, the Empire of Japan declared war on Germany, in part due to the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, and Japan became a member of the Entente powers. The Imperial Japanese Navy made a considerable contribution to the Allied war effort; however, the Imperial Japanese Army was more sympathetic to Germany, and aside from the seizure of Tsingtao, resisted attempts to become involved in combat. At the following Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Japan's proposal of amending a "racial equality clause" to the covenant of the League of Nations was rejected by the United States, Britain and Australia. Arrogance and racial discrimination towards the Japanese had plagued Japanese-Western relations since the forced opening of the country in the 1800s, and were again a major factor for the deterioration of relations in the decades preceeding World War 2. In 1924, for example, the US Congress passed the Exclusion Act that prohibited further immigration from Japan. Japanese intervention in Siberia and Russian Far East The overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II and the establishment of a Bolshevik government in Russia led to a separate peace with Germany and the collapse of the Eastern Front. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76648-7 - The Doctrines of US Security Policy: An Evaluation under International Law Heiko Meiertons Excerpt More information 1 Introduction ‘Right’ and ‘might’ are two antagonistic forces representing alternative principles for organising international relations. Considering the inter- action between these two forces, one can identify certain features: with regard to questions considered by states as being relevant or having vital importance to their own security international law serves as means of foreign policy, rather than foreign policy serving as a means of fostering international law.1 Given the nature of international law as a law of coordination and also the way in which norms are created under it, pre-legal, political questions of power are of far greater importance under international law than they are under domestic law.2 Despite an increasing codification of international law or even a constitutionalisation,3 international law lacks a principle which contradicts the assumption that states, based on their own power may act as they wish.4 In spite of the principle of sovereign equality, the legal relations under international law can be shaped to mirror the distribution of power much more than in domestic law.5 1 H. Morgenthau, Die internationale Rechtspflege, ihr Wesen und ihre Grenzen (Leipzig: Universitatsverlag¨ Robert Noske, 1929), also: Ph.D. thesis, Leipzig (1929), pp. 98–104; L. Henkin, How Nations Behave – Law and Foreign Policy (New York: Praeger, 1968), pp. 84–94. 2 F. Kratochwil, ‘Thrasymmachos Revisited: On the Relevance of Norms and the Study of Law for International Relations’, J.I.A. -

Kohima: Turning Occupational Japanese Interlude the Tides of War Hazards Walter Sim Monzurul Huq Robert Whiting 02 | FCCJ | AUGUST 2020

The Magazine of The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan August 2020 · Volume 52 · No. 8 RENOVATE AND RESET The 75th Anniversary of Peace in the Pacific Singapore’s Kohima: turning Occupational Japanese Interlude the tides of war Hazards Walter Sim Monzurul Huq Robert Whiting 02 | FCCJ | AUGUST 2020 In This Issue August 2020 · Volume 52 · No. 8 Contact the Editors Our August issue commemorates Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam [email protected] Agreement in the “Jewel Voice Broadcast” (Gyokuon-hōsō) at noon on Publisher FCCJ August 15 1945. The Imperial line and Japan itself were renovated, then reset for the Cold War in Asia. Editor Peter O’Connor Designer Julio Kohji Shiiki, tokyographics.com Editorial Assistant Naomichi Iwamura Photo Coordinator Michiyo Kobayashi Publications Committee THE FRONT PAGE Peter O’Connor (Chair), Suvendrini Kakuchi, Monzurul Huq, Robert Whiting, David McNeill 03 From the President FCCJ BOARD OF DIRECTORS By Khaldon Azhari President Khaldon Azhari, PanOrient News 1st Vice President Monzurul Huq, Daily Prothom Alo 2nd Vice President Robert Whiting, Freelance FROM THE ARCHIVES Treasurer Mehdi Bassiri, Associate Member Secretary Takashi Kawachi, Freelance Directors-at-Large 04 James Abegglen, Mehdi Bassiri, Associate Member Peter O’Connor, Freelance Guru of Japanese Management Akihiko Tanabe, Associate Member Charles Pomeroy Abigail Leonard, Freelance Kanji Gregory Clark, Freelance Associate Kanji Vicki Beyer, Associate Member FEATURES Ex-officio Thomas Høy Davidsen, Jyllands-Posten FCCJ COMMITTEE CHAIRS Associate Members Liaison War Ends: The 75th Keiko Packard, Yuusuke Wada Compliance Kunio Hamada, Yoshio Murakami DeRoy Memorial Scholarship Abigail Leonard Anniversary Issue Entertainment Sandra Mori Exhibitions Bruce Osborn 05 Singapore’s Japanese interlude Film Karen Severns Finance Mehdi Bassiri Walter Sim Food & Beverage Robert Kirschenbaum, Peter R. -

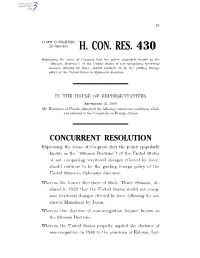

H. Con. Res. 430

IV 110TH CONGRESS 2D SESSION H. CON. RES. 430 Expressing the sense of Congress that the policy (popularly known as the ‘‘Stimson Doctrine’’) of the United States of not recognizing territorial changes effected by force, should continue to be the guiding foreign policy of the United States in diplomatic discourse. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SEPTEMBER 25, 2008 Mr. HASTINGS of Florida submitted the following concurrent resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Foreign Affairs CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Expressing the sense of Congress that the policy (popularly known as the ‘‘Stimson Doctrine’’) of the United States of not recognizing territorial changes effected by force, should continue to be the guiding foreign policy of the United States in diplomatic discourse. Whereas the former Secretary of State, Henry Stimson, de- clared in 1932 that the United States would not recog- nize territorial changes effected by force following the sei- zure of Manchuria by Japan; Whereas this doctrine of non-recognition became known as the Stimson Doctrine; Whereas the United States properly applied the doctrine of non-recognition in 1940 to the countries of Estonia, Lat- VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:03 Sep 26, 2008 Jkt 069200 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6652 Sfmt 6300 E:\BILLS\HC430.IH HC430 rwilkins on PROD1PC63 with BILLS 2 via, and Lithuania and every Presidential administration of the United States honored this doctrine until inde- pendence was restored to those countries in 1991; Whereas article 2, paragraph 4 of the Charter of the United Nations demonstrates -

Timeline for World War II — Japan

Unit 5: Crisis and Change Lesson F: The Failure of Democracy and Return of War Student Resource: Timeline for World War II — Japan Timeline for World War II — Japan Pre-1920: • 1853: American Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Tokyo harbor and forced the Japanese to allow trade with U.S. merchants with threat of military action. • 1858: Western nations forced Japan to sign the Unequal Treaties. These articles established export and import tariffs and the concept of "extraterritoriality" (i.e., Japan held no jurisdiction over foreign criminals in its land. Their trials were to be conducted by foreign judges under their own nation's laws). Japan had no power to change these terms. • 1868: Japan, in an effort to modernize and prevent future Western dominance, ousted the Tokugawa Shogunate and adopted a new Meiji Emperor. The next few decades saw rapid and successful industrialization during the Meiji Restoration. • 1899: With newly gained power from recent industrialization, Japan successfully renegotiated aspects of the Unequal Treaties. • 1899–1901: The Boxer Rebellion led China to a humiliating defeat by the Eight-Nation Alliance of Western powers including the United States and Japan, ceding more territory, and dealing one of the final blows to the struggling Qing Dynasty. • 1904–1905: The Russo-Japanese War began with a surprise attack and ended by an eventual Japanese victory over Imperial Russia. The Japanese took control of Korea. • 1914: During World War I, Japan and other Allies seized German colonial possessions. • 1919: Japan, as a member of the victorious Allies during World War I, gained a mandate over various Pacific islands previously part of the German colonial empire. -

IMPERIAL RESCRIPT WE, by Grace of Heaven, Emperor of Japan, Seated

IMPERIAL RESCRIPT WE, by grace of heaven, Emperor of Japan, seated on the Throne of the line unbroken for ages eternal, enjoin upon ye, Our loyal and brave subjects: We hereby declare war on the United States of America and the British Empire. The men and officers of Our Army and Navy shall do their utmost in prosecuting the war, Our public servants of various departments shall perform faithfully and diligently their appointed tasks, and all other subjects of Ours shall pursue their respective duties; the entire nation with a united will shall mobilize their total strength so that nothing will miscarry in the attainment of our war aims. To insure the stability of East Asia and to contribute to world peace is the far-sighted policy which was formulated by Our Great Illustrious Imperial Grandsire and Our Great Imperial Sire succeeding Him, and which We lay constantly to heart. To cultivate friendship among nations and to enjoy prosperity in common with all nations has always been the guiding principle of Our Empire's foreign policy. It has been truly unavoidable and far from Our wishes that Our empire has now been brought to cross swords with America and Britain. More than four years have passed since the government of the Chinese Republic, failing to comprehend the true intentions of Our Empire, and recklessly courting trouble, disturbed the peace of East Asia and compelled Our Empire to take up arms. Although there has been re- established the National Government of China, with which Japan has effected neighborly intercourse and cooperation, the regime which has survived at Chungking, relying upon American and British protection, still continues its fractricidal opposition. -

History of Central Europe

* . • The German Confederation existing since 1815 was dissolved • Instead of that the North German Commonwealth was constituted – 21 states – customs union, common currency and common foreign policy – the first step to unification • Prussian king became the President of this Commonwealth and the commander-in-chef of the army • Prussia provoked France to declare war on Prussia in 1870 • France was defeated at the battle of Sedan in September 1870 – French king Napoleon III was captured what caused the fall of the French Empire and proclamation of the third republic • Paris was besieged since September 1870 till January 1871 • January 1871 – The German Empire was proclaimed * Great powers at the end of the 19th century: • USA - the strongest • Germany (2nd world industrial area), the most powerful state in Europe, strong army, developed economy and culture • France – the bank of the world, 2nd strongest European state, succesful colonial politicis – colonies in Africa and in Asia • Great Britain – the greatest colonial power – its domain included the geatest colony – India,… • in Asia Japan – constitutional monarchy, development of industry, expansive politics • Austria-Hungary –cooperation with Germany, its foreign politics focused on the Balkan Peninsula • Russia – economicaly and politicaly the weakest state among the great powers, military-political system, absolute power of the Tsar, no political rights for citizens, social movement, expansion to Asia – conflicts with Japan and Great Britain * • 1879 – the secret agreement was concluded