The Private Journals of C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

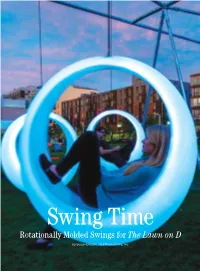

Rotationally Molded Swings for the Lawn on D

Swing Time Rotationally Molded Swings for The Lawn on D by Susan Gibson, JSJ Productions, Inc. 44 ROTOWORLD® | AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2017 Swing Time is a rotationally molded, interactive, and light- tear. The designers conferred with MCCA about manufacturing enabled swing that is uniquely tailored to the user. The hugely them with rotational molding and received their full approval. successful project, commissioned by the Massachusetts They then contacted Jim Leitz, Vice President of Marketing for Convention Center Authority (MCCA), was designed by award- Gregstrom Corporation. “This was a fun project because it was a winning Höweler + Yoon Architecture of Boston, MA and big deal in Boston and important to the success of The Lawn on rotomolded by Gregstrom Corporation of Woburn, MA. D,” said Leitz. The challenge was to create an interactive space for residents Gregstrom quoted the job in February and in March a in an urban setting and reflect the playful nature and purpose of purchase order was issued for the production and delivery of the The Lawn on D — a contemporary sculpture park bordering on swings in just 8 weeks. The swings would need to be installed at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center and D Street on The Lawn on D in time for the 2016 Memorial Day holiday. the city’s southern waterfront. “The swing’s responsive play Gregstrom contacted Sandy Saccia of Norstar Aluminum elements invite users to interact with the swings and with each Molds because they knew Norstar could deliver the required other, activating the urban park and creating a community tooling on time, which would allow them to deliver the swings laboratory in the Innovation District and South Boston by the required date. -

Downloads/2003 Essay.Pdf, Accessed November 2012

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91b0909n Author Alomaim, Anas Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Anas Alomaim 2016 © Copyright by Anas Alomaim 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 by Anas Alomaim Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Sylvia Lavin, Chair Kuwait started the process of its nation building just few years prior to signing the independence agreement from the British mandate in 1961. Establishing Kuwait’s as modern, democratic, and independent nation, paradoxically, depended on a network of international organizations, foreign consultants, and world-renowned architects to build a series of architectural projects with a hybrid of local and foreign forms and functions to produce a convincing image of Kuwait national autonomy. Kuwait nationalism relied on architecture’s ability, as an art medium, to produce a seamless image of Kuwait as a modern country and led to citing it as one of the most democratic states in the Middle East. The construction of all major projects of Kuwait’s nation building followed a similar path; for example, all mashare’e kubra [major projects] of the state that started early 1960s included particular geometries, monumental forms, and symbolic elements inspired by the vernacular life of Kuwait to establish its legitimacy. -

James Blair Historical Review, Volume 3

James Blair Historical Review Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 1 2012 James Blair Historical Review, Volume 3 Chris Phillibert College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/jbhr Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Phillibert, Chris (2012) "James Blair Historical Review, Volume 3," James Blair Historical Review: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/jbhr/vol3/iss1/1 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in James Blair Historical Review by an authorized editor of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Phillibert: JBHR, Vol. 3 The James Blair Historical Review ~ 2012 III Volume TTHEHE JJAMESAMES BBLAIRLAIR HHISTORICALISTORICAL RREVIEWEVIEW VVOLUMEOLUME IIIIII ~~ 2012201 Published by W&M ScholarWorks, 2012 1 James Blair Historical Review, Vol. 3 [2012], Iss. 1, Art. 1 https://scholarworks.wm.edu/jbhr/vol3/iss1/1 2 The James Blair Historical Review EDITORIAL BOARD Kyra Zemanick, Editor-in-Chief Andrew Frantz, Managing Editor Andrew Fickley, Submissions Editor Mason Watson, Layout Editor Caitlin Patterson, Business Manager Diana Ohanian, Publicity Manager Alex Hopkins, Publicity Manager PEER REVIEWERS James Blake Taylor Feenstra Tracy Jenkins Paul Burgess Grant Gill Camille Lorei Ciara Cryst Abby Gomulkiewicz Molly Michie Stephen D’Alessio Lauren Greene Mira Nair Ashley Deluce Stephen Hurley Emily Patterson Chase Hopkins Amy Schaffman FACULTY ADVISOR Dr. Hiroshi Kitamura Online: In addition to this printed issue, the James Blair Historical Review can also be accessed online at www.wm.edu/as/history/under- graduateprogram/The-James-Blair-Historical-Review/index.php. -

Architecture Program Report

MARCH 2013 REVISED JULY 2013 ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM REPORT NAAB VISIT FOR AccreDitation Patricia Seitz Master of Architecture Program Head / Program Coordinator Professor of Architecture Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.879.7677 Paul Hajian Chair - Architecture Department Professor of Architecture Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.879.7652 Jenny Gibbs Associate Dean of Graduate Programs Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.879.7181 Maureen Kelly Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.879.7365 Dawn Barrett President Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.879.7100 MASSachuSETTS COLLege OF Art AND DESIGN ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM REPORT 2013 ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM Report 2013 MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN / ARCHITECTURE / MARCH 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part ONE (I) - INSTITUTIONAL Support AND COMMITMENT to CONTINUOUS Improvement 4 Section 1: Identity and Self-Assessment 4 I.1.1 History and Mission 4 I.1.2 Learning Culture and Social Equity 18 I.1.3 Responses to the Five Perspectives 22 I.1.4 Long Range Planning 28 I.1.5 Self-Assessment Procedures 40 Section 2: Resources 48 I.2.1 Human Resources and Resource Development 48 I.2.2 Administrative Structure and Governance 69 I.2.3 Physical Resources 74 I.2.4 Financial Resources 92 I.2.5 Information Resources 95 Section 3: Institutional and Program Characteristics 101 I.3.1 Statistical Reports 101 I.3.2 Financial Reports 106 I.3.3 Faculty Credentials 107 Section 4: Policy Review 112 Part TWO (II) - EDucationaL OutcomeS -

2015 Architecture Program Report

MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM REPORT SEPTEMBER 2015 Massachusetts College of Art and Design Graduate Programs Architecture Program Report for 2016 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation Master of Architecture Track I - 102 Credits [non-pre-professional degree, 42 pre-professional credits + 60 graduate credits] Track II – 60 credits [preprofessional degree + 60 graduate credits] Year of the Previous Visit: 2013 Current Term of Accreditation: The professional architecture program: Master of Architecture was formally granted a three-year term of initial accreditation. The accreditation term is effective January 1, 2013. Submitted to: The National Architectural Accrediting Board Date: September 7, 2015 1 MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM REPORT SEPTEMBER 2015 Massachusetts College of Art and Design Graduate Programs 621 Huntington Avenue Boston, MA 02115 Program Administrator: Patricia Seitz, AIA, NCARB, LEED. Professor and Head, Graduate Architecture Program Chief administrator for the academic unit in which the program is located: Paul Paturzo, Interim Dean, Graduate Studies [email protected] Paul Hajian, Chair, Department of Architectural Design [email protected] Chief Academic Officer of the Institution: Ken Strickland, Provost / Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs [email protected] President of the Institution: Kurt Steinberg [email protected] Individual submitting the Architecture Program Report: Patricia Seitz Name of individual to whom questions should be directed: Patricia Seitz [email protected] 617-879-7677 Note: Due to the installation of MassArt’s new website in spring 2017, website addresses have been updated in this document where possible. As requested by the College, floor plans of college facilities most used by the architecture department have not been included in this public copy of MassArt’s APR. -

2006-2008 Undergraduate Course Catalog

SIMMONS COLLEGE Undergraduate Program Course Ca t a l o g 2 0 0 6 – 2 0 0 8 Addendum Available in Spring 2007 Co n t e n t s ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2 0 0 6 – 2 0 0 7 . 6 THE COLLEGE ABOUT SIMMONS . 8 BOSTON AND BEYOND . .9 THE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM . 1 1 The Simmons Education in Co n t e x t . 1 1 Academic Advising . 1 1 Program Planning . 1 2 M a j o r s . 1 2 M i n o r s . 1 3 Other Academic Programs . 1 3 Pre-law – Health Professions and Pre-medical – Accelerated Masters Degree – M a s t e r of Health Administration – Study Abroad Option – Credit for Prior Learning – Integrated Undergraduate/Graduate P r o g r a m s P a r t n e r s h i p s . 1 6 American University – Association of New American Colleges – Butler University – Colleges of the Fenway – Community Service Learning – Cornell University – Domestic Exchange Program: Fisk University, Mills College, Spelman College – English Institute of Harvard University – The Fenway Alliance – The Girls Get Connected Collaborative – Granada Institute of International Studies – Hebrew College – Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum – Museum of Fine Arts – New England Conservatory of Music – New England Philharmonic Orchestra – 92nd Street YWCA – Ritsumeikan University – Ryerson University – Yeditepe University Centers and Publications . 1 7 Center for Gender in Organizations – Gustavus Myers Center for the Study of Bigotry and Human Rights in North America – Scott/Ross Center for Community Service – Simmons Institute for Leadership and Change – Summer Institute in Children’s Literature – Zora Neale Hurston Literary Ce n t e r Degree Requirements . -

View Curriculum Vitae

Orwig 1 Timothy T. Orwig 11 Broadmarsh Ave. 617.817.4732 (cell) 508.850.8990 Wareham, MA 02571 [email protected] College and University Teaching Boston College, Boston, MA, 2014 through present; scheduled Fall 2018. Lecturer in Fine Arts: History of Architecture (Fall semesters) and Modern Architecture (Spring semesters); American Icons in 19th Century Art (Spring 2017); Art: Renaissance through Modern (Summer 2 2017); Nineteenth Century Art (Scheduled Fall 2018) Northeastern University, Boston, MA, 2012 through present Lecturer in School of Architecture: History of American Architecture and World Architecture (both halves of 2-semester survey) Lecturer in Department of Art + Design: Global History of Art & Design survey (both semesters: Ancient through Gothic & Renaissance to Present); Modern Art History; and Contemporary Art History (Approximately 3 sections/semester, 32 sections total) Emmanuel College, Boston, MA Fall 2017-Spring 2018 Lecturer in Art History: Survey of Art II Boston University, Boston, MA, 2000-2013 Lecturer, Metropolitan College at BU: Survey of World Art I, Spring 2013 Lecturer in American Studies: Art & Architecture of Boston, 2003-2011; Greater Boston and Its Neighborhoods, 2004 Lecturer for Summer Challenge: History of Boston, 2008-2010 Writing Fellow: Constructing Massachusetts: Writing about Architecture, Landscape, and Culture, 2003-2006 Museum Fellow: Researched Bowen House and its collections for Historic New England, 2002 Teaching Fellow for Art History: Introduction to Architecture, 2002 Graduate Assistant: -

Royal East Kent Regiment)

Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment) The Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment), formerly the 2 Origin of “The Buffs” 3rd Regiment of Foot, was a line infantry regiment of the British Army. It had a history dating back to 1572 and The 3rd Regiment’s nickname of “The Buffs” is said to was one of the oldest regiments in the British Army, being have originated in its use of protective buff coats—made third in order of precedence (ranked as the 3rd Regiment of soft leather— during service in the Netherlands in the of the line). The regiment provided distinguished service 17th century. Later they adopted buff-coloured facings over a period of almost four hundred years accumulating and waistcoats as uniform distinctions and wore equip- one hundred and sixteen battle honours. In 1881 under ment of natural buff leather rather than pipe-clayed the the Childers Reforms it was known as the Buffs (East customary white. Kent Regiment) and later, on 3 June 1935, was renamed the Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment). The name of “The Old Buffs” originated during the Battle of Dettingen in 1743, when the 31st (Huntingdonshire) In 1961 it was amalgamated with the Queen’s Own Royal Regiment of Foot marched past King George II and onto West Kent Regiment to form the Queen’s Own Buffs, the battlefield with great spirit. Mistaking them for the The Royal Kent Regiment which was later merged, on 3rd due to their similar buff facings, the sovereign called 31 December 1966, with the Queen’s Royal Surrey Regi- out, “Bravo, Buffs! Bravo!". -

Susana Noemitomasi Historia Económica

62 130 130 SUSANA NOEMI TOMASI HISTORIA ECONÓMICA MUNDIAL LA RELACIÓN ENTRE LAS CRISIS ECONOMICAS Y LAS GUERRAS TOMO VII: EN LA EDAD MODERNA CAPÍTULO I PRIMER CUARTO DEL SIGLO XVIII-EUROPA https://magatem.com.ar/ Página 1 https://magatem.com.ar/ Página 2 Editorial Magatem Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina Julio de 2021 Dibujo de tapa: pastel a la tiza, sobre papel misionero: denominado: “Hechos de Guerra” Realizado por Karina Valeria Woloj mail: [email protected] Editorial Magatem Acassuso 5808 (1440) Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires Argentina TE: 011- 46822431 Mail: [email protected] https://magatem.com.ar/ Página 3 INTRODUCCIÓN En éste último siglo de la Historia Moderna y comienzo de la Contemporánea, se perciben guerras civiles, teóricamente religiosas, pero indudablemente económicas, ya que los triunfadores de las mismas, se quedaban con los bienes de los derrotados y tal como indica Platón Polichinelle, significaron millones de muertos. Platón Polichinelle (1) indica que “Por el año de 1525 yo veo a cien mil paisanos alemanes fanatizados por vuestras reformas religiosas, y degollados por los partidarios de estas reformas; así es que desde sus principios, vuestra emancipación religiosa hizo en algunos meses tres veces más de víctimas que nuestra inquisición en el espacio de trescientos años. A este lago de sangre anabaptista agreguemos: Primero: la sangre que la Alemania derramó en sus guerras religiosas hasta el tratado de Wesfalia en 1648, que puso término a las espantosas carnicerías de la guerra llamada de treinta años. Segundo, la sangre que costó el triunfo del luteranismo de Dinamarca, en Suecia, en la Noruega, en Irlanda. -

Oral History Interview with Nelson Aldrich, 1982 January 22-1985 April 4

Oral history interview with Nelson Aldrich, 1982 January 22-1985 April 4 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Nelson Aldrich on January 22, 1982, March 10, 1982, and April 4, 1985. The interview took place in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and was conducted by Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. This is a rough transcription that may include typographical errors. What follows is a DRAFT TRANSCRIPT, which may contain typographical errors or inaccuracies. The content of this page is subject to change upon editorial review. Interview January 22, 1982 ROBERT BROWN: Beginning an interview on January 22, 1982, at Marblehead, Massachusetts, with Nelson Aldrich; I'm Bob Brown, the interviewer. And we want to talk about your life and your career, particularly as it's related to the arts. You were the son of an architect, William Aldrich? NELSON ALDRICH: That's right, William T. Aldrich. MR. BROWN: Where were you raised, or where did you spend your first years? MR. ALDRICH: My first years were -- well, I was born in New York City, but my mother and father came to Boston when I was about three. -

Published By: the Secretary of the Commonwealth, William Francis Galvin

Volume 37, Issue 1, January 4, 2017 The Central Register Published by: The Secretary of the Commonwealth, William Francis Galvin CENTRAL REGISTER Published weekly by William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth Volume 37, Issue 1, January 4, 2017 DESIGNER SERVICES Request for Proposals 1 GENERAL CONTRACTS Invitation to Bid 6 CONTRACTORS OBTAINING PLANS/SPECIFICATIONS 34 CONTRACT AWARDS 38 LEASE, RENTAL, SALE, PURCHASE, ACQUISITION OR DISPOSITION OF REAL PROPERTY Notice of Proposed Disposition of Real Property 42 Office of Lease Management 45 MISCELLANEOUS 48 LIST OF DEBARRED CONTRACTORS DCAMM 49 Attorney General 50 DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIAL ACCIDENTS DEBARMENT LIST 51 LIST OF DECERTIFIED CONTRACTORS DCAMM 52 SUPPLIER DIVERSITY OFFICE Companies Certified 53 Companies Decertified 58 DESIGNER SELECTION BOARD - The Central Register is a state publication of public contracting opportunities, contract awards and related information received by the Secretary of the Commonwealth under the provisions of M.G.L. c. 9, § 20A. William Francis Galvin Secretary of the Commonwealth STATE BOOKSTORE State House, Room 116 Boston, MA 02133 (617) 727-2834 CENTRAL REGISTER SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION The Central Register is available in electronic form only. The total subscription price is $100 per year. You may subscribe to this publication on the following website: http://www.sec.state.ma.us/PublicationSubscriptionPublic/Login.aspx Please feel free to contact the State Bookstore with any questions that you may have regarding your subscription. Phone: (617) 727-2834 Email: [email protected] ** State Agencies Only** CHECKS WILL NOT BE ACCEPTED FROM STATE AGENCIES. State agencies are required to use the IE/ITI system. State agencies must complete the following information in order for their subscription to be processed. -

UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM COURSE CATALOG 2016–2018 2 | SIMMONS COLLEGE UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CATALOG | 2016–2018 Table of Contents

UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM COURSE CATALOG 2016–2018 2 | SIMMONS COLLEGE UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CATALOG | 2016–2018 Table of Contents THE COLLEGE . 7 About Simmons . 7 The Educational Program . 8 The Simmons Education in Context . 8 Academic Advising . 8 Program Planning . 9 Table of Contents of Table Majors . 9 Minors . 10 Other Academic Programs . 10 n Honors n Pre-Law n Pre-Health and Pre-Medical n 3 + 1 Accelerated Master’s Degree n 4 + 1 Accelerated Master’s Degree n Study Abroad n Credit for Prior Learning Degree Requirements . 12 • Degree Requirements • Department or Program Recommendation • Completion of 128 Semester Hours with a Passing Evaluation The Simmons PLAN (Purpose Leadership ActioN) . 14 Marks and Evaluations . 25 Academic Honors and Recognition Programs . 26 Principles and Policies . 27 Student Principles . 27 Educational Record Privacy Policy . 28 Equal Access Policy . 28 Withdrawal from the College . 28 Community Commitment to Diversity . 28 Notice of Non-Discrimination and Grievance Procedure . 29 Grievance Procedure . 30 Information for Students with Disabilities . 30 Religious Observance . 30 Other Policies . 31 Administration . 31 Admission . 32 First-Year Students . 32 Transfer Students . 35 International Students . 37 Adult Undergraduate Students . 38 2016–2018 | SIMMONS COLLEGE UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CATALOG | 3 Financial Aid . 40 Scholarships and Grants . 40 Loans: Federal and Institutional . 41 Parental Loan Programs and Payment Plans . 41 Part-time Employment . 42 Applying for Financial Aid . 42 Registration and Financial Information . 43 Expenses: 2016–2017 . 43 Payment Policies . 43 Refund Policies . 45 Dropping a Course . 46 Registration and Billing . 47 . 48 Guide to Course Descriptions Table of Contents of Table 4 | SIMMONS COLLEGE UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CATALOG | 2016–2018 DEPARTMENTS AND PROGRAMS .