The Roots of Social Order in the Union Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil War Guide1

Produced by Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal Contents Teacher Guide 3 Activity 1: Billy Yank and Johnny Reb 6 Activity 2: A War Map 8 Activity 3: Young People in the Civil War 9 Timeline of the Civil War 10 Activity 4: African Americans in the Civil War 12 Activity 5: Writing a Letter Home 14 Activity 6: Political Cartoons 15 Credits Content: Barbara Glass, Glass Clarity, Inc. Newspaper Activities: Kathy Liber, Newspapers In Education Manager, The Cincinnati Enquirer Cover and Template Design:Gail Burt For More Information Border Illustration Graphic: Sarah Stoutamire Layout Design: Karl Pavloff,Advertising Art Department, The Cincinnati Enquirer www.libertyontheborder.org Illustrations: Katie Timko www.cincymuseum.org Photos courtesy of Cincinnati Museum Center Photograph and Print Collection Cincinnati.Com/nie 2 Teacher Guide This educational booklet contains activities to help prepare students in grades 4-8 for a visit to Liberty on the Border, a his- tory exhibit developed by Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal.The exhibit tells the story of the American Civil War through photographs, prints, maps, sheet music, three-dimensional objects, and other period materials. If few southern soldiers were wealthy Activity 2: A War Map your class cannot visit the exhibit, the slave owners, but most were from activity sheets provided here can be used rural agricultural areas. Farming was Objectives in conjunction with your textbook or widespread in the North, too, but Students will: another educational experience related because the North was more industri- • Examine a map of Civil War America to the Civil War. Included in each brief alized than the South, many northern • Use information from a chart lesson plan below, you will find objectives, soldiers had worked in factories and • Identify the Mississippi River, the suggested class procedures, and national mills. -

Eastmont High School Items

TO: Board of Directors FROM: Garn Christensen, Superintendent SUBJECT: Requests for Surplus DATE: June 7, 2021 CATEGORY ☐Informational ☐Discussion Only ☐Discussion & Action ☒Action BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND ADMINISTRATIVE CONSIDERATION Staff from the following buildings have curriculum, furniture, or equipment lists and the Executive Directors have reviewed and approved this as surplus: 1. Cascade Elementary items. 2. Grant Elementary items. 3. Kenroy Elementary items. 4. Lee Elementary items. 5. Rock Island Elementary items. 6. Clovis Point Intermediate School items. 7. Sterling Intermediate School items. 8. Eastmont Junior High School items. 9. Eastmont High School items. 10. Eastmont District Office items. Grant Elementary School Library, Kenroy Elementary School Library, and Lee Elementary School Library staff request the attached lists of library books be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Sterling Intermediate School Library staff request the attached list of old social studies textbooks be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont Junior High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books and textbooks for both EJHS and Clovis Point Intermediate School be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books for both EHS and elementary schools be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. ATTACHMENTS FISCAL IMPACT ☒None ☒Revenue, if sold RECOMMENDATION The administration recommends the Board authorize said property as surplus. Eastmont Junior High School Eastmont School District #206 905 8th St. NE • East Wenatchee, WA 98802 • Telephone (509)884-6665 Amy Dorey, Principal Bob Celebrezze, Assistant Principal Holly Cornehl, Asst. -

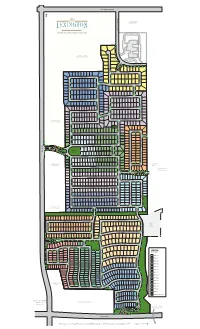

Lexington Phases Mastermap RH HR 3-24-17

ELDORADO PARKWAY MAMMOTH CAVE LANE CAVE MAMMOTH *ZONED FUTURE LIGHT RETAIL MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY MAJESTIC PRINCE CIRCLE MAMMOTH CAVE LANE T IN O P L I A R E N O D ORB DRIVE ARISTIDES DRIVE MACBETH AVENUE MANUEL STREETMANUEL SPOKANE WAY DARK STAR LANE STAR DARK GIACOMO LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDSTONE MANOR GRINDSTONE FUNNY CIDE COURT FUNNY THUNDER GULCH WAY BROKERS TIP LANE MANUEL STREETMANUEL E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND TRAIL LEONATUS LANE LEONATUS PONDER LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTERGREEN DRIVE COIT ROAD COIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD COUNT TURF COUNT DRIVE AMENITY SMARTY JONES STREET CENTER STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD 2 DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY 5 CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 1 Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE FLYING EBONY STREET LIGHT RETAIL Park AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE CONQUISTADOR COURT CONQUISTADOR LUCKY DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY OXBOW AVENUE OXBOW CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 4 WHIRLAWAY DRIVE 9 IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER ROAD C WAR EMBLEM PLACE WAR A N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R I V E 14DUST COMMANDER COURT CIRCLE PASS FORWARD DETERMINE DRIVE SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUIET RD. TIM TAM CIRCLE EASY GOER AVENUE LEGEND PILLORY DRIVE PILLORY BY PHASES HALMA HALMA TRAIL 11 PHASE 1 A PROUD CLAIRON STREET M E MIDDLEGROUND PLACE -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

English Reading List 2021 - 2022 Oib

ENGLISH READING LIST 2021 - 2022 OIB NEW BOOKS • Such a Fun Age, Kiley Read • Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell • I Am Not Your Baby Mama, Candice Brathwaite • The Five, Hallie Rubenhold • Sweet Sorrow, David Nicholls • Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart • Home Going, Yaa Gyasi • Airhead, Emily Maitliss • Americanah, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi • Girl, Woman, Other, Bernadine Evaristo • The Power, Naomi Alderman • Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race, Reni Eddo-Lodge MODERN CLASSICS/FICTION • The Catcher in the Rye, JD Salinger • Birdsong/Charlotte Gray, Sebastian Faulks • A Prayer for Owen Meany/The World According to Garp, John Irving • When We Were Orphans/The Remains of the Day/Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro • A Kestrel for a Knave, Barry Hines • Lord of the Flies, William Golding • The Great Gatsby, F.Scott Fitzgerald • The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Carson McCullers • The Pearl/East of Eden/The Grapes of Wrath/The Long Valley, John Steinbeck • Rebecca/Jamaica Inn, Daphne Du Maurier • One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey • The Book Thief, Markus Zusak • The Shock of the Fall, Markus Zusak • White Teeth, Zadie Smith • Brighton Rock, Graham Greene • Gilead, Marilynne Robinson Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle 35 Cromwell Road, London SW7 2DG Tél : +44 (0)20 7584 6322 www.lyceefrancais.org.uk • Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, Roddy Doyle • The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini • A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry • Vile Bodies/Brideshead Revisited/Decline and Fall, Evelyn Waugh • On the Road, Jack Kerouac • The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy • -

Kindergarten the World Around Us

Kindergarten The World Around Us Course Description: Kindergarten students will build upon experiences in their families, schools, and communities as an introduction to social studies. Students will explore different traditions, customs, and cultures within their families, schools, and communities. They will identify basic needs and describe the ways families produce, consume, and exchange goods and services in their communities. Students will also demonstrate an understanding of the concept of location by using terms that communicate relative location. They will also be able to show where locations are on a globe. Students will describe events in the past and in the present and begin to recognize that things change over time. They will understand that history describes events and people of other times and places. Students will be able to identify important holidays, symbols, and individuals associated with Tennessee and the United States and why they are significant. The classroom will serve as a model of society where decisions are made with a sense of individual responsibility and respect for the rules by which they live. Students will build upon this understanding by reading stories that describe courage, respect, and responsible behavior. Culture K.1 DHVFULEHIDPLOLDUSHRSOHSODFHVWKLQJVDQGHYHQWVZLWKFODULI\LQJGHWDLODERXWDVWXGHQW¶V home, school, and community. K.2 Summarize people and places referenced in picture books, stories, and real-life situations with supporting detail. K.3 Compare family traditions and customs among different cultures. K.4 Use diagrams to show similarities and differences in food, clothes, homes, games, and families in different cultures. Economics K.5 Distinguish between wants and needs. K.6 Identify and explain how the basic human needs of food, clothing, shelter and transportation are met. -

Lex Mastermap Handout

ELDORADO PARKWAY M A MM *ZONED FUTURE O TH LIGHT RETAIL C A VE LANE MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY M A J E MAMMOTH CAVE LANE S T T IN I C O P P L I R A I N R E C N E O C D I R C L ORB DRIVE E A R I S T MACBETH AVENUE I D E S D R I V E M SPOKANE WAY D ANUEL STRE ARK S G I A C T O AR LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 M O E L T A N E 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDS FUN N T Y CIDE ONE THUNDER GULCH WAY M C ANOR OU BROKERS TIP LANE R T M ANUEL STRE E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A E T DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND VIEW LEON PONDER LANE A TUS LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTE R GREEN DRIVE C OIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD C OUNT R O TURF DRIVE AD S AMENITY M A CENTER R T Y JONES STRE STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD E T L 5 2 UC K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 1 A Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE V FLYING EBONY STREET A LIGHT RETAIL L C Park ADE DRIVE AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE C L ONQUIS UC O XBOW K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 4 T A ADOR V A A VENUE L C ADE DRIVE WHIRLAWAY DRIVE C OU R 9T IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER C W A AR EMBLEM PL N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R A O R CE I AD V E DUST COMMANDER COURT FO DETERMINE DRIVE R W ARD P 14 ASS CI SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUI R CLE E T R TIM TAM CIRCLE D . -

Military History Digest #323

H-War Military History Digest #323 Blog Post published by David Silbey on Sunday, December 30, 2018 Ancient: •Ultra-Precise Ice Core Sampling and the Explosive Cause of the Dark Ages https://kottke.org/18/12/ultra-precise-ice-core-sampling-and-the-explosive-cause-of-the-da... Medieval: •Cawdor Castle Highland, Scotland - Atlas Obscura https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/cawdor-castle •The Nature of War and Its Impact on Society During the Barons' War, 1264-67 - Medievalists.net http://www.medievalists.net/2018/12/the-nature-of-war-and-its-impact-on-society-during-the... 18th Century (to 1815): •A Hot Dinner and a Bloody Supper: St. Helenas Christmas Rebellions of 1783 and 1811 Age of Revolutions https://ageofrevolutions.com/2018/12/17/a-hot-dinner-and-a-bloody-supper-st-helenas-christ... •Global Maritime History Book Review: Lincoln: "Trading in War" - Global Maritime History https://globalmaritimehistory.com/book-review-lincoln-trading-in-war/ •Historical Firearms - Patrick Ferguson and His Rifle - Journal of The... http://www.historicalfirearms.info/post/181140457294/patrick-ferguson-and-his-rifle-journa... •Life and Death at Valley Forge - 10 Surprising Facts About the Revolutionary War's Darkest Winter - MilitaryHistoryNow.com https://militaryhistorynow.com/2018/12/02/six-months-at-valley-forge-10-astonishing-facts-... •What's Wrong With This Picture? - Seven Strange Facts About One of America's Most Iconic Paintings - MilitaryHistoryNow.com https://militaryhistorynow.com/2018/12/22/whats-wrong-with-this-picture-seven-strange-fact... 1815-1861: •Remembering West Points Eggnog Riot of 1826 | Mental Floss http://mentalfloss.com/article/72776/west-points-eggnog-riot-1826?fbclid=IwAR3PbfMMlQkyKTX.. -

An Overview of the New Testament in Eight Weeks Arden C. Autry, Phd

An Overview of the New Testament in Eight Weeks Arden C. Autry, PhD Introduction An eight-week overview cannot cover everything in the New Testament. Instead we will focus on some of the key events and some of the most important contributions by individual NT writers. With that as our aim we hope to gain a sense of the New Testament’s unity, diversity, and theological development. The approach of this series will be partly chronological, but only in a general way. Obviously the events of the Gospels precede the events of Acts, and the events in Acts partially overlap with the historical contexts for some of Paul’s Epistles. But the earliest Epistle of Paul was almost certainly written before the first Gospel was written, and the Book of James was probably written before Paul’s earliest. With a strict chronological order being out of the question for such a series, the approach taken will be somewhat canonical (taking the books in the order found in the Bible). So, for example, we will treat Matthew before Mark, even though most NT scholars (including the author of this series) believe Mark was written before Matthew. When we get to the Epistles of Paul in Lessons 5-6, the canonical approach will not serve as well. The canonical order of Paul’s Epistles goes generally from longest to shortest, not from earliest to latest (e.g., the Thessalonian letters were written years before Romans). To attempt a chronological approach, however, would involve too much repetition and historical arguments for the chosen order. -

Southeastern Ohio's Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil

They Fought the War Together: Southeastern Ohio’s Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil War A Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Gregory R. Jones December, 2013 Dissertation written by Gregory R. Jones B.A., Geneva College, 2005 M.A., Western Carolina University, 2007 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Dr. Leonne M. Hudson, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Bradley Keefer, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Members Dr. John Jameson Dr. David Purcell Dr. Willie Harrell Accepted by Dr. Kenneth Bindas, Chair, Department of History Dr. Raymond A. Craig, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................iv Introduction..........................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1: War Fever is On: The Fight to Define Patriotism............................................26 Chapter 2: “Wars and Rumors of War:” Southeastern Ohio’s Correspondence on Combat...............................................................................................................................60 Chapter 3: The “Thunderbolt” Strikes Southeastern Ohio: Hardships and Morgan’s Raid....................................................................................................................................95 Chapter 4: “Traitors at Home”: -

Kentucky Derby Winners Vs. Kentucky Derby Winners

KENTUCKY DERBY WINNERS VS. KENTUCKY DERBY WINNERS Winners of the Kentucky Derby have faced each other 43 times. The races have occurred 17 times in New York, nine in California, nine in Maryland, six in Kentucky, one in Illinois and one in Canada. Derby winners have run 1-2 on 12 occasions. The older Derby winner has prevailed 24 times. Three Kentucky Derby winners have been pitted against one another twice, including a 1-2-3 finish in the 1918 Bowie Handicap at Pimlico by George Smith, Omar Khayyam and Exterminator. Exterminator raced against Derby winners 15 times and finished ahead of his rose-bearing rivals nine times. His chief competitor was Paul Jones, who he beat in seven of 10 races while carrying more weight in each affair. Date Track Race Distance Derby Winner (Age, Weight) Finish Derby Winner (Age, Weight) Finish Nov. 2, 1991 Churchill Downs Breeders’ Cup Classic 1 ¼ M Unbridled (4, 126) 3rd Strike the Gold (3, 122) 5th June 26, 1988 Hollywood Park Hollywood Gold Cup H. 1 ¼ M Alysheba (4,126) 2nd Ferdinand (5, 125) 3rd April 17, 1988 Santa Anita San Bernardino H. 1 1/8 M Alysheba (4, 127) 1st Ferdinand (5, 127) 2nd March 6, 1988 Santa Anita Santa Anita H. 1 ¼ M Alysheba (4, 126) 1st Ferdinand (5, 127) 2nd Nov. 21, 1987 Hollywood Park Breeders’ Cup Classic 1 ¼ M Ferdinand (4, 126) 1st Alysheba (3, 122) 2nd Oct. 6, 1979 Belmont Park Jockey Club Gold Cup 1 ½ M Affirmed (4, 126) 1st Spectacular Bid (3, 121) 2nd Oct. 14, 1978 Belmont Park Jockey Club Gold Cup 1 ½ M Seattle Slew (4, 126) 2nd Affirmed (3, 121) 5th Sept. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins .