An Overview of the New Testament in Eight Weeks Arden C. Autry, Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Reading List 2021 - 2022 Oib

ENGLISH READING LIST 2021 - 2022 OIB NEW BOOKS • Such a Fun Age, Kiley Read • Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell • I Am Not Your Baby Mama, Candice Brathwaite • The Five, Hallie Rubenhold • Sweet Sorrow, David Nicholls • Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart • Home Going, Yaa Gyasi • Airhead, Emily Maitliss • Americanah, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi • Girl, Woman, Other, Bernadine Evaristo • The Power, Naomi Alderman • Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race, Reni Eddo-Lodge MODERN CLASSICS/FICTION • The Catcher in the Rye, JD Salinger • Birdsong/Charlotte Gray, Sebastian Faulks • A Prayer for Owen Meany/The World According to Garp, John Irving • When We Were Orphans/The Remains of the Day/Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro • A Kestrel for a Knave, Barry Hines • Lord of the Flies, William Golding • The Great Gatsby, F.Scott Fitzgerald • The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Carson McCullers • The Pearl/East of Eden/The Grapes of Wrath/The Long Valley, John Steinbeck • Rebecca/Jamaica Inn, Daphne Du Maurier • One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey • The Book Thief, Markus Zusak • The Shock of the Fall, Markus Zusak • White Teeth, Zadie Smith • Brighton Rock, Graham Greene • Gilead, Marilynne Robinson Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle 35 Cromwell Road, London SW7 2DG Tél : +44 (0)20 7584 6322 www.lyceefrancais.org.uk • Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, Roddy Doyle • The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini • A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry • Vile Bodies/Brideshead Revisited/Decline and Fall, Evelyn Waugh • On the Road, Jack Kerouac • The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy • -

SF Commentary 106

SF Commentary 106 May 2021 80 pages A Tribute to Yvonne Rousseau (1945–2021) Bruce Gillespie with help from Vida Weiss, Elaine Cochrane, and Dave Langford plus Yvonne’s own bibliography and the story of how she met everybody Perry Middlemiss The Hugo Awards of 1961 Andrew Darlington Early John Brunner Jennifer Bryce’s Ten best novels of 2020 Tony Thomas and Jennifer Bryce The Booker Awards of 2020 Plus letters and comments from 40 friends Elaine Cochrane: ‘Yvonne Rousseau, 1987’. SSFF CCOOMMMMEENNTTAARRYY 110066 May 2021 80 pages SF COMMENTARY No. 106, May 2021, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough, VIC 3088, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 61-3-9435 7786. .PDF FILE FROM EFANZINES.COM. For both print (portrait) and landscape (widescreen) editions, go to https://efanzines.com/SFC/index.html FRONT COVER: Elaine Cochrane: Photo of Yvonne Rousseau, at one of those picnics that Roger Weddall arranged in the Botanical Gardens, held in 1987 or thereabouts. BACK COVER: Jeanette Gillespie: ‘Back Window Bright Day’. PHOTOGRAPHS: Jenny Blackford (p. 3); Sally Yeoland (p. 4); John Foyster (p. 8); Helena Binns (pp. 8, 10); Jane Tisell (p. 9); Andrew Porter (p. 25); P. Clement via Wikipedia (p. 46); Leck Keller-Krawczyk (p. 51); Joy Window (p. 76); Daniel Farmer, ABC News (p. 79). ILLUSTRATION: Denny Marshall (p. 67). 3 I MUST BE TALKING TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 34 TONY THOMAS TO MY FRIENDS, PART 1 THE BOOKER PRIZE 2020 READING EXPERIENCE 3, 7 41 JENNIFER BRYCE A TRIBUTE TO YVONNNE THE 2020 BOOKER PRIZE -

Awards and Persons in News

Awards, Persons & Places Parakram Diwas The Government of India recently announced that the birth anniversary of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose is to be celebrated as “Parakram Diwas”. Parakram Diwas means Courage Day. Netaji was born on January 23, 1897. The Central Government and the Bengal Government are to begin the yearlong celebrations of 125th birth anniversary year on January 23, 2021. Contents Netaji started a newspaper called “Swaraj”. He had written a book called “The Indian Struggle”. The term “Jai Hind” was coined by Netajji Subhash Chandra Bose. He formed the All India Forward Bloc as a part of the Indian National Congress in 1939. Flight Lieutanant Bhawana Kanth Bhawana Kanth is to become the first woman fighter pilot to take part in the Republic Day parade. She was one among the first women fighter pilots inducted in Indian Air Force in 2016. The other fighter pilots inducted into the Indian Air Force were Avani Chaturvedi and Mohana Singh. Contents Bhawana Kanth In 2019, Bhawana Kanth became the first female fighter pilot of India to qualify to undertake combat missions. She received the Nari Shakti Puraskar from President of India Ramnath Kovind in March 2020. Jammu & Kashmir: GI tag for Gucchi Mushroom The Jammu and Kashmir Government recently sought GI tag for Gucchi mushroom. The Gucchi mushrooms are highly expensive and are full of health benefits. 500 grams of Gucchi mushrooms cost Rs 18,000. Recently, GI Tag was provided to Saffron of Jammu and Kashmir. They are referred to “May Mushrooms” in North America. The Gucchi mushrooms cannot be cultivated commercially. -

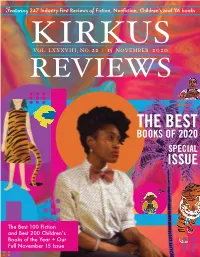

Kirkus Reviewer, Did for All of Us at the [email protected] Magazine Who Read It

Featuring 247 Industry-First Reviews of and YA books KIRVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 22 K | 15 NOVEMBERU 202S0 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Fiction and Best 200 Childrenʼs Books of the Year + Our Full November 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: Peak Reading Experiences Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief No one needs to be reminded: 2020 has been a truly god-awful year. So, TOM BEER we’ll take our silver linings where we find them. At Kirkus, that means [email protected] Vice President of Marketing celebrating the great books we’ve read and reviewed since January—and SARAH KALINA there’s been no shortage of them, pandemic or no. [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor With this issue of the magazine, we begin to roll out our Best Books ERIC LIEBETRAU of 2020 coverage. Here you’ll find 100 of the year’s best fiction titles, 100 [email protected] Fiction Editor best picture books, and 100 best middle-grade releases, as selected by LAURIE MUCHNICK our editors. The next two issues will bring you the best nonfiction, young [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor adult, and Indie titles we covered this year. VICKY SMITH The launch of our Best Books of 2020 coverage is also an opportunity [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor for me to look back on my own reading and consider which titles wowed LAURA SIMEON me when I first encountered them—and which have stayed with me over the months. -

BOOKERJEVA NAGRADA (Man Booker Prize) Je Nagrada Za

BOOKERJEVA NAGRADA (Man Booker Prize) Je nagrada za najboljši roman v angleškem jeziku, ki ga je napisal avtor iz Commonwealtha ali Irske, podeljuje jo Booker Prize Foundation od leta 1969. In velja za eno najuglednejših književnih nagrad v angleško govorečem svetu. Nagrajene knjige, ki jih imamo v naši knjižnični zbirki, so označene debelejše: 2020 Douglas Stuart: SHUGGIE BAIN 2019 Margaret Atwood: TESTAMENTI in Bernardine Evaristo: GIRL, WOMAN, OTHER 2018 Anna Burns: MILKMAN 2017 Geroge Saunders: LINCOLN IN THE BARDO 2016 Paul Beatty: THE SELLOUT 2015 Marlon James: A BRIEF HISTORY OF SEVEN KILLINGS 2014 Richard Flanagan: THE NARROW ROAD TO THE DEEP NORTH (Ozka pot globoko do severa, 2017) 2013 Eleanor Catton: THE LUMINARIES 2012 Hilary Mantel: BRING UP THE BODIES 2011 Julian Barnes: THE SENSE OF AN ENDING (Smisel konca, 2012) 2010 Howard Jacobson: THE FINKLER QUESTION (Finklersko vprašanje, 2012) 2009 Hilary Mantel: WOLF HALL 2008 Aravind Adiga: THE WHITE TIGER (Beli tiger, 2010; prev. Marko Trobevšek) 2007 Anne Enright: THE GATHERING (Shajanje, 2013) 2006 Kiran Desai: THE INHERITANCE OF LOSS (Dediščina izgube, 2007) 2005 John Banville: THE SEA (Morje, 2006) 2004 Alan Hollinghurst: THE LINE OF BEAUTY (Linija lepote, 2006) 2003 DBC Pierre: VERNON GOD LITTLE (Vernon Gospod Little, 2004) 2002 Yann Martel: LIFE OF PI (Pijevo življenje, 2004) 2001 Peter Carey: TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG 2000 Margaret Atwood: THE BLIND ASSASSIN (Slepi morilec, 2010) 1999 J. M. Coetzee: DISGRACE (Sramota, 2004) 1998 Ian McEwan: AMSTERDAM (Amsterdam, 2004) 1997 Arundhati Roy: THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS (Bog majhnih stvari, 2000) 1996 Graham Swift: LAST ORDERS (Zadnja želja, 2007) 1995 Pat Barker: THE GHOST ROAD 1994 James Kelman: HOW LATE IT WAS, HOW LATE (Kako pozno, pozno je bilo, 2006) 1993 Roddy Doyle: PADDY CLARKE HA HA HA (1995) 1992 Michael Ondaatje: THE ENGLISH PATIENT (Angleški pacient, 1998) Barry Unsworth: SACRED HUNGER 1991 Ben Okri: THE FAMISHED ROAD (Cesta sestradanih, 2016) 1990 A. -

Books I've Read This Spring Jodi R.'S Booktalk – April 9, 2021 Via Zoom

Books I’ve Read This Spring Jodi R.’s Booktalk – April 9, 2021 via Zoom for the Library BooksTalk Group The Searcher South of the Buttonwood Tree by Tana French (October 2020) by Heather Webber (July 2020) This book satisfied my two cravings: mysteries; and an Irish setting. Cal Hooper’s Blue Bishop and Sarah Grace Landreneau Fulton are the two protagonists. Living dedication to his job as a Chicago police officer cost him his marriage. After in small-town Buttonwood, Alabama, their lives have briefly crossed in the past. retiring from being a detective who found missing people, he moved to a When an abandoned baby is found in the woods, both strong women need to dilapidated cottage in Ireland for serenity. Asking for his help in finding a dig deep to find out what each really wants passionately enough to make missing brother, a high school student showed up at Cal’s door. Despite sacrifices. Secrets are revealed that, when assembled, surprise them, their warnings from others to stay away from the case, Cal became invested in families, and the town. There is magic realism: Blue has a supernatural knack for finding the young man who’d disappeared. FICTION; MYSTERY finding lost items or people; and the Buttonwood Tree spits out prophecies on wooden buttons. FICTION; MAGIC REALISM On The Come Up by Angie Thomas (February 2019) Young Adult; author of The Hate U Give. Bri Jackson is sixteen years old and wants to be the best rapper ever. Distracted from school by her Dear Child by Romy Hausmann (2019) family’s poverty, empty refrigerator and unpaid rent/utility bills, Bri Similar to Room, by Emma Donoghue, this mystery is about whether Lena is the feels like shooting to stardom as a rapper will be her family’s ticket out young woman who was kidnapped fourteen years earlier. -

Indiebestsellers

Indie Bestsellers Fiction Week of 11.04.20 HARDCOVER PAPERBACK 1. The Searcher 1. The Overstory Tana French, Viking, $27 Richard Powers, Norton, $18.95 2. The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue 2. Circe V.E. Schwab, Tor, $26.99 Madeline Miller, Back Bay, $16.99 3. A Time for Mercy 3. This Tender Land John Grisham, Doubleday, $29.95 William Kent Krueger, Atria, $17 ★ 4. The Sentinel ★ 4. Shuggie Bain Lee Child, Andrew Child, Delacorte Press, $28.99 Douglas Stuart, Grove Press, $17 5. Anxious People 5. Homegoing Fredrik Backman, Atria, $28 Yaa Gyasi, Vintage, $16.95 6. The Vanishing Half 6. The Topeka School Brit Bennett, Riverhead Books, $27 Ben Lerner, Picador, $17 7. Leave the World Behind 7. Ninth House Rumaan Alam, Ecco, $27.99 Leigh Bardugo, Flatiron Books, $17.99 ★ 8. The Cold Millions 8. The Nickel Boys Jess Walter, Harper, $28.99 Colson Whitehead, Anchor, $15.95 9. Transcendent Kingdom 9. Nothing to See Here Yaa Gyasi, Knopf, $27.95 Kevin Wilson, Ecco, $16.99 ★ 10. Memorial 10. Normal People Bryan Washington, Riverhead Books, $27 Sally Rooney, Hogarth, $17 11. The Evening and the Morning 11. The Song of Achilles Ken Follett, Viking, $36 Madeline Miller, Ecco, $16.99 ★ 12. Snow 12. Parable of the Sower John Banville, Hanover Square Press, $27.99 Octavia E. Butler, Grand Central, $16.99 13. Mexican Gothic 13. The Testaments Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Del Rey, $27 Margaret Atwood, Anchor, $16.95 14. All the Devils Are Here 14. Girl, Woman, Other Louise Penny, Minotaur, $28.99 Bernardine Evaristo, Grove Press/Black Cat, $17 15. -

EXCEL CIVILS ACADEMY DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS Date: 21-11-2020

EXCEL CIVILS ACADEMY DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS Date: 21-11-2020 1. With respect to “Sustainable Alternative Towards Affordable Transportation (SATAT)”, consider the following statements: 1) It provides for generating gas from municipal waste as well as forest and agri waste. 2) The gas produced at compressed bio-gas plants can be used as fuel to power automobiles. Which of the statements given above is/are correct? a) 1 only b) 2 only c) Both 1 and 2 d) Neither 1 nor 2 2. The Virtual Court (traffic) and e-Challan project have been recently inaugurated in which of the following north eastern states? a) Nagaland b) Assam c) Sikkim d) Tripura 3. Recently, who among the following has won the 2020 Booker Prize for fiction with his/her debut novel Shuggie Bain? a) Margaret Atwood b) Bernardine Evaristo c) Anna Burns d) Douglas Stuart 4. Seismic Survey Campaign by Oil India Limited will be undertaken in which of the following states? a) Maharashtra b) Tamil Nadu c) Assam d) Odisha 5. With respect to “World Fisheries Day”, consider the following statements: 1) It started in 1950 where “World Forum of Fish Harvesters & Fish Workers” met at New Delhi leading to formation of “World Fisheries Forum”. 2) It is celebrated every year on November 21 throughout the fishing communities to highlight the importance of lives of water creatures to humans. Which of the statements given above is/are correct? a) 1 only b) 2 only c) Both 1 and 2 d) Neither 1 nor 2 6. With respect to ““Awaas Diwas”, consider the following statements: 1) It is celebrated to commemorate the launch of Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana - Gramin (PMAY-G). -

This Bookshelf: 2020 Books Links to All Steve Hopkins' Bookshelves

This Bookshelf: 2020 Books Links to All Steve Hopkins’ Bookshelves Web Page PDF/epub/Searchable Link to Latest Book Reviews: Book Reviews Blog Links to Current Bookshelf: Pending and Read 2020 Books 2020 Books Links to 549 Books Read or Skipped in 2020 2020 Bookshelf 2020 Bookshelf Links to All Books from 1999 All Books Authors A through All Books Authors A through through 2020 Authors A-G G G Links to All Books from 1999 through 2020 Authors H-M All Books Authors H All Books Authors H through M through M Links to All Books from 1999 All Books Authors N through All Books Authors N through through 2020 Authors N-Z Z Z Book of Books: An ebook of Book of Books books read, reviewed or skipped from 1999 through 2020 This web page lists all 360 books reviewed by Steve Hopkins at http://bkrev.blogspot.com during 2020 as well as 189 books relegated to the Shelf of Ennui. You can click on the title of a book or on the picture of any jacket cover to jump to amazon.com where you can purchase a copy of any book on this shelf. Key to Ratings: I love it ***** I like it **** It’s OK *** I don’t like it ** I hate it * Click on Title (Click on Link Blog Picture to to purchase at Author(s) Rating Comments Date Purchase at amazon.com) amazon.com Endless. For an immersive mediation on war, read Salar Abdoh’s novel titled, Out of Mesopotamia. From the perspective of protagonist Saleh, a journalist, we struggle to make sense of those who are engaged in what Out of seems like endless war. -

The New York Times Notable Books 2020, Opens a New Window

100 Notable Books of 2020 The year’s notable fiction, poetry and nonfiction, selected by the editors of The New York Times Book Review The Aosawa Murders BY RIKU ONDA. Translated by Alison Watts. FICTION. Onda’s strange, engrossing novel — patched together from scraps of interviews, letters, newspaper articles and the like — explores the sweltering day that 17 members of the Aosawa family died after drinking poisoned sake and soda. The Beauty in Breaking: A Memoir BY MICHELE HARPER. NONFICTION. MEMOIR. When Harper was a teenager, she drove her brother to the hospital to get treated for a bite her father had inflicted. There, she glimpsed a world she wanted to join. “The Beauty in Breaking” is her memoir of becoming an emergency room physician. It’s also a profound statement on the inequities in medical care today. The Beauty of Your Face BY SAHAR MUSTAFAH. FICTION. In the Chicago suburbs, a gunman opens fire at a school for Palestinian girls. Mustafah rewinds from the shooting to the principal’s childhood as a newly arrived immigrant. Hers is a story of outsiders coming together in surprising and uplifting ways. Becoming Wild: How Animal Cultures Raise Families, Create Beauty, and Achieve Peace BY CARL SAFINA. NONFICTION Safina, the ecologist and author of many books about animal behavior, here delves into the world of chimpanzees, sperm whales and macaws to make a convincing argument that animals learn from one another and pass down culture in a way that will feel very familiar to us. Beheld BY TARASHEA NESBIT. FICTION. In this plain-spoken and lovingly detailed historical novel, the story of the Mayflower Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony is refracted through the prism of female characters. -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal the Criterion: an International Journal in English Vol

AboutUs: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ ContactUs: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ EditorialBoard: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 12, Issue-II, April 2021 ISSN: 0976-8165 Review of Shuggie Bain: The 2020 Booker Prize Novel Title: Shuggie Bain (Paperback) Author: Douglas Stuart Publisher: Picador Year: 2020 Pages: 430 Language: English ISBN: 978-1-5290-6441-4 Price: Rs. 499 Reviewed by: Mekha Mathew M.A English Student St. Thomas College, Kozhencherry, Kerala, India. "Flames are not just the end, they are also the beginning. For everything that you have destroyed can be rebuilt. From your own ashes you can grow again." (Douglas Stuart) A debut novel by the Scottish American writer Douglas Stuart, Shuggie Bain creates an amazing portrayal of intimacy, courage and love. It describes the wrenching story of a young boy who experiences humiliation from society as well as struggles in living a life www.the-criterion.com 369 The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 12, Issue-II, April 2021 ISSN: 0976-8165 along with his alcoholic mother Agnes. His mother's alcoholism and his mystifying sexuality contribute to it to be a heartbreaking work of addiction, sexuality and love. The novel is set in Glasgow in the 1980s in a post-industrial working-class society. It tells the story of the protagonist Shuggie Bain, the youngest of the three children, who leads a depressing life with his mother Agnes. -

Celebrating and Remembering Mothers

THE LACONIA DAILY SUN, Thursday, May 6, 2021 — Page 13 Celebrating and remembering mothers Elizabeth Howard with her mother, Betty. (Courtesy photo) ast year the 2020 to an episode of” Krista gie Bain is a difficult book to read as Podcast (found on Apple or Spotify), Booker Prize, the Tippet’s on Being” (New its sadness penetrates and absorbs the follow her on Instagram at elizh24 or L leading award Hampshire Public reader. Yet throughout the book we feel send her a note at: elizabeth@laconia- for literary fiction, was Radio). She was in con- Shuggie’s connection and love for his dailysun.com She is an author and awarded to Shuggie Bain versation with Dario mother. journalist. Her books include Ned (Grove Press, New York, Robledo, an artist, who Happy Mother’s Day. Let us salute O’Gorman: A Glance Back, a book she 2020). The author, Doug- was discussing his work these remarkable women and keep edited (Easton Studio Press, 2015), las Stuart, is a Scottish around memory and loss. their connections with us. “If you A Day with Bonefish Joe (David R. American now living in It was such a fascinating remember, I’ll remember.” Godinez, 2015), Queen Anne’s Lace and Manhattan. He was born exchange I have since lis- ••• Wild Blackberry Pie, (Thornwillow in Glasgow, Scotland and tened to the episode sev- Listen to Elizabeth on the Short Fuse Press, 2011). grew up with two older eral times since. siblings in a public hous- In his work Robledo ing project. Their mother has focused on memory presenting its first 2021 struggled as an alcoholic with the thought that special exhibits and drug addict trying to by Elizabeth Howard “If you remember, I’ll from May 1 –June 10 piece together her own Special to The Laconia Daily Sun remember.