Allaback National Historic Landmark Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

How Did Frank Lloyd Wright Establish a New Canon of American

“ The mother art is architecture. Without an architecture of our own we have no soul of our own civilization.” -Frank Lloyd Wright How did Frank Lloyd Wright establish a new canon of American architecture? Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) •Considered an architectural/artistic genius and THE best architect of last 125 years •Designed over 800 buildings •Known for ‘Prairie Style’ (really a movement!) architecture that influenced an entire group of architects •Believed in “architecture of democracy” •Created an “organic form of architecture” Prairie School The term "Prairie School" was coined by H. Allen Brooks, one of the first architectural historians to write extensively about these architects and their work. The Prairie school shared an embrace of handcrafting and craftsmanship as a reaction against the new assembly line, mass production manufacturing techniques, which they felt created inferior products and dehumanized workers. However, Wright believed that the use of the machine would help to create innovative architecture for all. From your architectural samples, what may we deduce about the elements of Wright’s work? Prairie School • Use of horizontal lines (thought to evoke native prairie landscape) • Based on geometric forms . Flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves . “Environmentally” set: elevations, overhangs oriented for ventilation . Windows grouped in horizontal bands called ribbon fenestration that used shifting light . Window to wall ratio affected exterior & interior . Overhangs & bays reach out to embrace . Integration with the landscape…Wright designed inside going out . Solid construction & indigenous materials (brick, wood, terracotta, stucco…natural materials) . Open continuous plan & spaces; use of dissolving walls, but connected spaces Prairie School •Designed & used “glass screens” that echoed natural forms •Created Usonian homes for the “masses” Frank Lloyd Wright, Darwin D. -

Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston the Story of How One of the Oldest American Cities Became the Epicenter of Concrete Modernist Architecture

Media Contact: Dan Scheffey Ellen Rubin [email protected] [email protected] (212) 979-0058 (212) 909-2625 HEROIC: CONCRETE ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEW BOSTON THE STORY OF HOW ONE OF THE OLDEST AMERICAN CITIES BECAME THE EPICENTER OF CONCRETE MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE As a worldwide phenomenon, concrete modernism represents one of the major architectural movements of the postwar years, but in Boston it was more transformative across civic, cultural, and academic projects than in any other major city in the United States. Concrete provided an important set of architectural opportunities and challenges for the design community, which fully explored the material’s structural and sculptural qualities. From 1960 to 1976, concrete was used by some of the world's most influential architects in the transformation of Boston including Marcel Breuer, Eduardo Catalano, Henry N. Cobb, Araldo Cossutta, Kallmann and McKinnell, Le Corbusier, I. M. Pei, Paul Rudolph, Josep Lluís Sert, and The Architects Collaborative—creating a vision for the city’s widespread revitalization under the banner of the “New Boston.” Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston presents the historical context and new critical profiles of the buildings that defined Boston during this remarkable period, showing the city as a laboratory for refined experiments in concrete and new strategies in urban planning. Heroic further adds to our understanding of the movement’s broader implications through essays by noted historians and interviews with several key practitioners of HEROIC: Concrete Architecture the time: Peter Chermayeff, Henry N. Cobb, Araldo Cossutta, Michael and the New Boston McKinnell, Tician Papachristou, Tad Stahl, and Mary Otis Stevens. -

Doing Business Search - People

Doing Business Search - People MOCS PEOPLE ID ORGANIZATION NAME 50136 CASTLE SOFTWARE INC 158890 J2 147-07 94TH AVENUE LI LLC 160281 SDF67 SPRINGFIELD BLVD OWNER LLC 129906 E-J ELECTRIC INSTALLATION CO. 63414 NEOPOST USA INC 56283 MAKE THE ROAD NEW YORK 53828 BOSTON TRUST & INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT COMPANY 89181 FALCON BUILDER INC 105272 STERLING INFOSYSTEMS INC 107736 SIEGEL & STOCKMAN 160919 UTECH PRODUCTS INC 49631 LIRO GIS INC. 12881 THE GORDIAN GROUP INC. 64818 ZUCKER'S GIFTS INC 52185 JAMAICA CENTER FOR ARTS & LEARNING INC 146694 GOOD SHEPHERD SERVICES 156009 ATOMS INC. 116226 THE MENTAL HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK CITY INC. 150172 SOSA USA LLC Page 1 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People PERSON FIRST NAME PERSON MIDDLE NAME SCOTT FRANK C NATALIE DEBORAH L LUCIA B MEHMET ANDREW PHILIPPE J JAMES J MICHAEL HARRY H MARVIN CATHY HUIYING RACHEL SIDRA SUSAN UZI B Page 2 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People PERSON LAST NAME PERSON_NAME_SUFFIX FISCHER PRG NATIONAL URBAN FUNDS LLC SULLIVAN DEBT FUND HLDINGS LLC LAMBRAIA ADAIR AXT SANTINI PALAOGLU REIBEN DALLACORTE COSTANZO BAILEY MELLON STERNBERG HUNG KITAY QASIM SHANKLIN SCHEFFER Page 3 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People RELATIONSHIP TYPE CODE MCT EWN EWN MCT MCT CFO OWN CFO CFO CEO MCT MCT MCT CEO CEO MCT COO COO CEO Page 4 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People DOING BUSINESS START DATE 09/21/0016 11/20/0019 01/14/0020 03/10/0016 08/08/0008 04/03/0021 11/19/0008 06/02/0014 09/02/0016 03/03/0013 04/03/0021 06/02/0018 08/02/0008 12/05/0008 04/14/0015 02/22/0018 06/05/0019 03/08/0014 01/03/0020 Page 5 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People DOING BUSINESS END DATE Page 6 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People 65572 RUSSELL TRUST COMPANY 53596 MOHAWK LTD 68208 ST ANN'S ABH OWNER LLC 136274 NEW YORK CITY CENTER INC. -

AIA 0001 Guidebook.Indd

CELEBRATE 100: AN ARCHITECTURAL GUIDE TO CENTRAL OKLAHOMA is published with the generous support of: Kirkpatrick Foundation, Inc. National Trust for Historic Preservation Oklahoma Centennial Commission Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Offi ce Oklahoma City Foundation for Architecture American Institute of Architects, Central Oklahoma Chapter ISBN 978-1-60402-339-9 ©Copyright 2007 by Oklahoma City Foundation for Architecture and the American Institute of Architects Central Oklahoma Chapter. CREDITS Co-Chairs: Leslie Goode, AssociateAIA, TAParchitecture Melissa Hunt, Executive Director, AIA Central Oklahoma Editor: Rod Lott Writing & Research: Kenny Dennis, AIA, TAParchitecture Jim Gabbert, State Historic Preservation Offi ce Tom Gunning, AIA, Benham Companies Dennis Hairston, AIA, Beck Design Catherine Montgomery, AIA, State Historic Preservation Offi ce Thomas Small, AIA, The Small Group Map Design: Geoffrey Parks, AIA, Studio Architecture CELEBRATE 100: AN Ryan Fogle, AssociateAIA, Studio Architecture ARCHITECTURAL GUIDE Cover Design & Book Layout: TO CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Third Degree Advertising represents architecture of the past 100 years in central Oklahoma Other Contributing Committee Members: and coincides with the Oklahoma Bryan Durbin, AssociateAIA, Centennial celebration commencing C.H. Guernsey & Company in November 2007 and the 150th Rick Johnson, AIA, Frankfurt-Short- Bruza Associates Anniversary of the American Institute of Architects which took place in April Contributing Photographers: of 2007. The Benham Companies Frankfurt-Short-Bruza -

Frank Lloyd Wright

'SBOL-MPZE8SJHIU )JTUPSJD"NFSJDBO #VJMEJOHT4VSWFZ '$#PHL)PVTF $PNQJMFECZ.BSD3PDILJOE Frank Lloyd Wright Historic American Buildings Survey Sample: F. C. Bogk House Compiled by Marc Rochkind Frank Lloyd Wright: Historic American Buildings Survey, Sample Compiled by Marc Rochkind ©2012,2015 by Marc Rochkind. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form or by any means (including electronic) without permission in writing from the copyright holder. Copyright does not apply to HABS materials downloaded from the Library of Congress website, although it does apply to the arrangement and formatting of those materials in this book. For information about other works by Marc Rochkind, including books and apps based on Library of Congress materials, please go to basepath.com. Introduction The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) was started in 1933 as one of the New Deal make-work programs, to employ jobless architects, draftspeople, and photographers. Its purpose is to document the nation’s architectural heritage, especially those buildings that are in danger of ruin or deliberate destruction. Today, the HABS is part of the National Park Service and its repository is in the Library of Congress, much of which is available online at loc.gov. Of the tens of thousands HABS buildings, I found 44 Frank Lloyd Wright designs that have been digitized. Each HABS survey includes photographs and/or drawings and/or a report. I’ve included here what the Library of Congress had–sometimes all three, sometimes two of the three, and sometimes just one. There might be a single photo or drawing, or, such as in the case of Florida Southern College (in volume two), over a hundred. -

SCOREBOARD Basketball

20—MANCHESTER HERALD. Monday. March 4.1991 SCOREBOARD TUESDAY Royd 1-2, Wood 52), Los Angslaa 2-10 (DIvac 24, Alabama 30) dki not play. NExt: vs. (Instigator, fighting), 13:53; Nolan, Qua, rnidor 1-1, Wbrthy 16, EJohnaon 51, ParMna 51, Florida at Naahvll, j, Tsnn, Friday. (fightaig), 13:53; Sokic, Qua (hooking), 1536; Tstiola 51, Scott 06). Foulad out-Nons. 25. Virginia (2310) did not play. NExt va. Hockey Gmis, QuE (charging), 1 6 3 8 Coif Basketball Rabounda—Houston 62 (1-Smith 22), Los An- Wbka ForEst at Chartotts, N C.. Frkfoy. Third PEriod—8 QuEbEc, Hough 10 (Hikoc, galas S3 (Worthy 10). AaaUts—Houaton 13 Sakic), 1362 (pp). 6, QuEbEc, M lEr 4 (Sakic, LOCAL NEWS INSIDE How women’s Top 25 fared Hough), 19:34. PEnaltiEs—JEnnings, Har (Maxwal. tCSmito. F l^ 13), Los AngoIss 24 Doral Open scores NBA standings (EJohnaon 8). Total touls-Houaton 23. Los How IhE AssociatEd PrEss' Top 25 womEn's NHL standings (rougNng), 136; Raglan, QuE, doubla minor Angaiss 20. Tachnicals—Houaton illogal Mam s farEd Sunday: W ALES CO N FER EN CE (rougNng), 136; Brown, Hor (unaportsmaNIkE MIAMI (AP) — Full and partial acor^ Sunday i A m i M C O N FE R E N C E dsfonaa 3, Los Angalaa Bagal datartas. Wordy. P a trick D iv isio n condiict), 239; Qillip QuE (unaportamaNHw during thE lightning-suspEndEd ktorth round of ■ Parkade subdivision approved. AtlMUeDIvtaton 1. Virginia (27-2) lost to dam son 65-62. A— 17,506. 2. Pann StatE (231) did not play. -

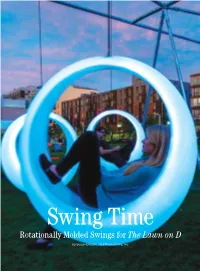

Rotationally Molded Swings for the Lawn on D

Swing Time Rotationally Molded Swings for The Lawn on D by Susan Gibson, JSJ Productions, Inc. 44 ROTOWORLD® | AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2017 Swing Time is a rotationally molded, interactive, and light- tear. The designers conferred with MCCA about manufacturing enabled swing that is uniquely tailored to the user. The hugely them with rotational molding and received their full approval. successful project, commissioned by the Massachusetts They then contacted Jim Leitz, Vice President of Marketing for Convention Center Authority (MCCA), was designed by award- Gregstrom Corporation. “This was a fun project because it was a winning Höweler + Yoon Architecture of Boston, MA and big deal in Boston and important to the success of The Lawn on rotomolded by Gregstrom Corporation of Woburn, MA. D,” said Leitz. The challenge was to create an interactive space for residents Gregstrom quoted the job in February and in March a in an urban setting and reflect the playful nature and purpose of purchase order was issued for the production and delivery of the The Lawn on D — a contemporary sculpture park bordering on swings in just 8 weeks. The swings would need to be installed at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center and D Street on The Lawn on D in time for the 2016 Memorial Day holiday. the city’s southern waterfront. “The swing’s responsive play Gregstrom contacted Sandy Saccia of Norstar Aluminum elements invite users to interact with the swings and with each Molds because they knew Norstar could deliver the required other, activating the urban park and creating a community tooling on time, which would allow them to deliver the swings laboratory in the Innovation District and South Boston by the required date. -

Free Executive Summary

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/573.html We ship printed books within 1 business day; personal PDFs are available immediately. Biographical Memoirs V.50 Office of the Home Secretary, National Academy of Sciences ISBN: 0-309-59898-2, 416 pages, 6 x 9, (1979) This PDF is available from the National Academies Press at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/573.html Visit the National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council: • Download hundreds of free books in PDF • Read thousands of books online for free • Explore our innovative research tools – try the “Research Dashboard” now! • Sign up to be notified when new books are published • Purchase printed books and selected PDF files Thank you for downloading this PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may contact our customer service department toll- free at 888-624-8373, visit us online, or send an email to [email protected]. This book plus thousands more are available at http://www.nap.edu. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF File are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Distribution, posting, or copying is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Request reprint permission for this book. i e h t be ion. om r ibut f r t cannot r at not Biographical Memoirs o f NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES however, version ng, i t paper book, at ive at rm o riginal horit ic f o e h t he aut t om r as ing-specif t ion ed f peset y http://www.nap.edu/catalog/573.html Biographical MemoirsV.50 publicat her t iles creat is h t L f M of and ot X om yles, r f st version print posed e h heading Copyright © National Academy ofSciences. -

Chapter 7: Urban Design and Visual Resources

Chapter 7: Urban Design and Visual Resources 7.1 Introduction This chapter assesses the Proposed Action’s potential effects on urban design and visual resources. Per the 2014 City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) Technical Manual, the urban design and visual resources assessment is undertaken to determine whether and how a project or action may change the visual experience of a pedestrian, focusing on the components of the project or action that may have the potential to affect the arrangement, appearance, and functionality of the built and natural environment. According to the CEQR Technical Manual, urban design is defined as the totality of components—including streets, buildings, open spaces, wind, natural resources, and visual resources—that may affect a pedestrian’s experience of public space. A visual resource is defined as the connection from the public realm to significant natural or built features, including views of the waterfront, public parks, landmark structures or districts, otherwise distinct buildings or groups of buildings, and natural resources. As described in Chapter 1, “Project Description,” the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) is proposing zoning map and zoning text amendments that would collectively affect approximately 78 blocks in Greater East Midtown, in Manhattan Community Districts 5 and 6 (collectively, the “Proposed Action”). The Proposed Action is intended to reinforce the area’s standing as a one of the City’s premiere business districts, support the preservation of landmarks, and provide for above- and below-grade public realm improvements as contained in the Public Realm Improvement Concept Plan (the “Concept Plan”) described in Chapter 1, “Project Description.” Many aspects of urban design are controlled by zoning, and because the Proposed Action would entail changes to zoning and related development-control mechanisms, the Proposed Action therefore may have the potential to result in changes to urban design.