Gwendolyn Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

Improving the Technical Knowledge and Background Level in Engineering Training by the Education Digitalization Process

E3S Web of Conferences 273, 12099 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127312099 INTERAGROMASH 2021 Improving the technical knowledge and background level in engineering training by the education digitalization process Konstantin Kryukov, Svetlana Manzhilevskaya*, Konstantin Tsapko, and Irina Belikova Don State University, 344000, Rostov-on-Don, Russia Abstract. The modern technical education digitalization implies an increase in the role of the information component in the training of students. At the same time there is a certain gap between the modern technologies training and the understanding of the fact that construction industry is the mixture of historically formed features and the current state of the industry. Nowadays construction industry is under continuous technical development. The main danger of an insufficient attention to the special aspects of the construction development is the neglect of the preservation of cultural background and architectural heritage, which can be observed in the modern life. The article deals with the issues of improving the effectiveness of the educational process of students by introducing into the educational training process not only modern methods of designing building structures, but also the issues of understanding the history of the emergence of individual construction objects. The construction object can't appear out of nothing. All constructive solution is preceded by a historical situation the situation of cultural and architectural heritage. However, there is no discernible connection between technical education and the humanities and social sciences. The authors use historical examples to justify the need for the use of elements of the humanities by a teacher of a higher technical educational institution with the introduction of the capabilities of modern digital information modeling technologies. -

Would You Believe L.A.? (Revisited)

WOULD YOU BELIEVE L.A.? (REVISITED) Downtown Walking Tours 35th Anniversary sponsored by: Major funding for the Los Angeles Conservancy’s programs is provided by the LaFetra Foundation and the Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation. Media Partners: Photos by Annie Laskey/L. A. Conservancy except as noted: Bradbury Building by Anthony Rubano, Orpheum Theatre and El Dorado Lofts by Adrian Scott Fine/L.A. Conservancy, Ace Hotel Downtown Los Angeles by Spencer Lowell, 433 Spring and Spring Arcade Building by Larry Underhill, Exchange Los Angeles from L.A. Conservancy archives. 523 West Sixth Street, Suite 826 © 2015 Los Angeles Conservancy Los Angeles, CA 90014 Based on Would You Believe L.A.? written by Paul Gleye, with assistance from John Miller, 213.623.2489 . laconservancy.org Roger Hatheway, Margaret Bach, and Lois Grillo, 1978. ince 1980, the Los Angeles Conservancy’s walking tours have introduced over 175,000 Angelenos and visitors alike to the rich history and culture of Sdowntown’s architecture. In celebration of the thirty-fifth anniversary of our walking tours, the Los Angeles Conservancy is revisiting our first-ever offering: a self-guided tour from 1978 called Would You Believe L.A.? The tour map included fifty-nine different sites in the historic core of downtown, providing the basis for the Conservancy’s first three docent-led tours. These three tours still take place regularly: Pershing Square Landmarks (now Historic Downtown), Broadway Historic Theatre District (now Broadway Theatre and Commercial District), and Palaces of Finance (now Downtown Renaissance). In the years since Would You Believe L.A.? was created and the first walking tours began, downtown Los Angeles has undergone many changes. -

WEST STREET BUILDING, 90 West Street and 140 Cedar Street (Aka 87-95 West Street, 21-25 Albany Street, and 136-140 Cedar Street), Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission May 19, 1998, Designation List 293 LP-1984 WEST STREET BUILDING, 90 West Street and 140 Cedar Street (aka 87-95 West Street, 21-25 Albany Street, and 136-140 Cedar Street), Borough of Manhattan. Built 1905-07; architect, Cass Gilbert. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 56, Lot 4. On March 10, 1998, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the West Street Building, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No . 1) . The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Five persons, including a representative of the owner and representatives of the New York Landmarks Conservancy and the Municipal Art Society, spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. A statement supporting designation has been received from Council Member Kathryn Freed. Summary The West Street Building, one of three major Downtown office buildings designed by Cass Gilbert, was built in 1905-07 for the West Street Improvement Corporation, a partnership headed by Howard Carroll. Carroll was president of two asphalt companies and vice-president of his father-in-law's Starin Transportation Company, which had major river shipping interests. Although today separated from the Hudson River by the landfill supporting Battery Park City, the site of the West Street Building originally had a highly visible location facing the waterfront along West Street. Carroll conceived of his project as a first-class skyscraper office building for the shipping and railroad industries. In addition to Carroll's companies, the building soon filled up with tenants including major companies in the transportation industry. -

Ideology As Dystopia: an Interpretation of "Blade Runner" Author(S): Douglas E

Ideology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of "Blade Runner" Author(s): Douglas E. Williams Source: International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique, Vol. 9, No. 4, (Oct., 1988), pp. 381-394 Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1600763 Accessed: 25/04/2008 20:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sageltd. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org InternationalPolitical ScienceReview (1988), Vol. 9, No. 4, 381-394 Ideology as Dystopia: An Interpretation of Blade Runner DOUGLASE. -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

“500 Days in Downtown L.A.” Walking Tour

“500 DAYS IN DOWNTOWN L.A.” WALKING TOUR Selected historic locations from the 2009 Fox Searchlight film “(500) Days of Summer” For much more information about the rich history of this area, including these and other landmarks, take the Los Angeles Conservancy’s walking tour, Downtown Renaissance: Spring & Main. For details, visit laconservancy.org/tours [Suggested route] Start at: SAN FERNANDO BUILDING 400 South Main Street (at Fourth Street) Original Building: John F. Blee, 1907 Addition (top two stories): R. B. Young, 1911 Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #728 Listed in the National Register of Historic Places In the film, Old Bank DVD serves as the video & record store. • Designed in the Renaissance Revival style • Commissioned by James B. Lankershim, one of the largest landholders in California (his father Isaac helped develop the San Fernando Valley for farming) • Originally had a café, billiard room, and Turkish bath in the basement for tenants • Achieved local attention in 1910, when a series of police raids occurred on the sixth floor due to illegal gambling in the rooms • Redeveloped by Gilmore Associates; reopened in 2000 as seventy loft- style apartments—one of the early projects that sparked downtown’s current renaissance Look diagonally across Main Street (northwest corner of Fourth & Main): “500 Days in Downtown L.A.” Walking Tour Page 1 of 6 VAN NUYS HOTEL (Barclay Hotel) 103 West Fourth Street Morgan and Walls, 1896 Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #288 In the film, the Barclay lobby serves as the hangout for -

FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT, Borough of Manhattan

FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION REPORT 1978 City of New York Edward I . Koch, Mayor Landmarks Preservation Commission Kent L. Barwick, Chairman Morris Ketchum, Jr., Vice Chairman Commissioners R. Michael Brown Thomas J. Evans Elisabeth Coit James Marston Fitch George R. Collins Marie V. McGovern William J. Conklin Beverly Moss Spatt FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT 66 - c 22 Water DESIGNATED NOV. 14, 1978 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION., COMMISSION FTB-HD Landmarks Preservation Commission November 14, 1978, Designation List 120 LP-0994 FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT, Borough of Manhattan BOUNDARIES The property bounded by the southern curb line of Pearl Street, the western curb line of Coenties Slip, the northern curb line of Water Street, and the eastern curb line of Broad Street, Manhattan. TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on this area which is now proposed as an Historic District (Item No. 14). Three persons spoke in favor of the proposed designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. -1 FTB-HD Introduction The Fre.unces Tavern Block Historic District, bounded by Fearl, Broad, and Water Streets, and Coenties Slip, stands today as a vivid reminder of the early history and development of this section of Manhattan. Now a single block of low-rise commercial buildings dating from the 19th century--with the exception of the 18th-century Fraunces Tavern--it contrasts greatly with the modern office towers surrounding it. The block, which was created entirely on landfill, was the first extension of the Manhattan shoreline for commercial purposes, and its development involved some of New York's most prominent families. -

Bradbury Building

AN IRREPLACEABLE COMBINATION BRADBURY OF HISTORIC ELEGANCE & BUILDING MODERN CLASS 300-310 S. BROADWAY BUILDING HISTORY The Bradbury, an antique architectural treasure of Los Angeles, was built in 1893 by mining millionaire Lewis Bradbury. The architect, George Wyman, was inspired by a 1880s science fiction novel on a utopian civilization in the year 2000. Costing an enormous $500,000 to construct ($325,000 over the original budget), Lewis Bradbury successfully accomplished his goal of creating a building that would perpetuate his name. BUILDING HIGHLIGHTS • The oldest commercial office building in downtown Los Angeles • Across the street from the world-renowned Grand Central Market, offering a vast array of eateries • Abundant month-to-month public parking with 10 structures and lots all within a two-block radius • Top-of-the-line ownership, attentive on-site property management, and 24/7 security Grand Central Market BUILDING FEATURES • Five stories of impeccable office suites immersed within ornate cast iron, polished wood, rich marble, and glazed brick, and crowned with an extraordinary skylight atrium illuminating the entire building with natural light • Beautiful creative spec suites available consisting of modern glass offices and conference rooms, hardwood flooring, and high-end kitchen finishes along with historic 125-year-old red brick walls, operable windows, and exposed wood ceilings. • Balconies surrounding the court that provide access to the suites • Two distinct open cage elevators in free-standing grillwork shafts • Symmetric -

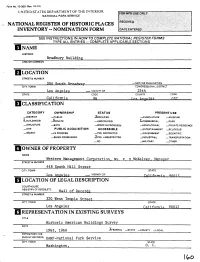

Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74> UNITEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Bradbury Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 3Q4 South Broadway _NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles — VICINITY OF 25th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 T.0<5 Angles 037 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC JfecCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BuiLDiNG(S) PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED K.COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED J^YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Western Management Mr n McKelveyf Manager STREET & NUMBER 448 South Hill Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles VICINITY OF Califnrrn a QfiHI LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 520. West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California 90012 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1965, 1968 -^FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS QAHP-National Park Service CITY. TOWN STATE Washington, D. C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED J£uNALTERED JiORIGINALSITE -

Ramsey County History Published by the RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Editor: Virginia Brainard Kunz

RAMSEY Ramsey County Historical Society COUNTY “History close to home” Landmark Center, 75 W. 5th St. St. Paul, MN 55102 HISTORY Ramsey County History Published by the RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Editor: Virginia Brainard Kunz Contents Beer Capital of the State St. Paul’s Historic Family Breweries by Gary J. Brueggmann................................. Page 3 Volum e 16 Num ber 2 Montgomery Schuyler Takes on ‘the West’ By Patricia M u rp h y .................................... Page 16 1910’s ‘One-horse’ Gladstone Recalled By Lucile A r n o ld ............ ............................ Page 21 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY is published semi annually and copyrighted 1981 by the Ramsey County Historical Society, Landmark Center, 75 West Fifth Street, St. Paul, Minnesota 55102. Membership in the Society carries with it a subscription to Ramsey County Cover Photo: This photograph o f the Yoerg Brewery, History. Single issues sell for $3 Correspondence nestling up against the bluffs o f St. Paul’s West Side, was concerning contributions should be addressed to the taken in 1933. The brewery was located at Ohio and Ethel editor. The Society assumes no responsibility for statements made by contributors. Manuscripts and other streets. Photos with the story on St. Paul'sfamily brewer editorial material are welcomed but no payment can be ies are from the collections o f the Minnesota Historical made for contributions. All articles and other editorial Society. Sketches for the Montgomery Schuyler story are material submitted will be carefully read and published, if reproducedfrom Vol. LXXXHI, Number 497, o f Harper's accepted as space permits. New Monthly Magazine for 1891 (pages 736-755).