(Part 1): Management of Male Urethral Stricture Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urological Trauma

Guidelines on Urological Trauma D. Lynch, L. Martinez-Piñeiro, E. Plas, E. Serafetinidis, L. Turkeri, R. Santucci, M. Hohenfellner © European Association of Urology 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. RENAL TRAUMA 5 1.1 Background 5 1.2 Mode of injury 5 1.2.1 Injury classification 5 1.3 Diagnosis: initial emergency assessment 6 1.3.1 History and physical examination 6 1.3.1.1 Guidelines on history and physical examination 7 1.3.2 Laboratory evaluation 7 1.3.2.1 Guidelines on laboratory evaluation 7 1.3.3 Imaging: criteria for radiographic assessment in adults 7 1.3.3.1 Ultrasonography 7 1.3.3.2 Standard intravenous pyelography (IVP) 8 1.3.3.3 One shot intraoperative intravenous pyelography (IVP) 8 1.3.3.4 Computed tomography (CT) 8 1.3.3.5 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 9 1.3.3.6 Angiography 9 1.3.3.7 Radionuclide scans 9 1.3.3.8 Guidelines on radiographic assessment 9 1.4 Treatment 10 1.4.1 Indications for renal exploration 10 1.4.2 Operative findings and reconstruction 10 1.4.3 Non-operative management of renal injuries 11 1.4.4 Guidelines on management of renal trauma 11 1.4.5 Post-operative care and follow-up 11 1.4.5.1 Guidelines on post-operative management and follow-up 12 1.4.6 Complications 12 1.4.6.1 Guidelines on management of complications 12 1.4.7 Paediatric renal trauma 12 1.4.7.1 Guidelines on management of paediatric trauma 13 1.4.8 Renal injury in the polytrauma patient 13 1.4.8.1 Guidelines on management of polytrauma with associated renal injury 14 1.5 Suggestions for future research studies 14 1.6 Algorithms 14 1.7 References 17 2. -

Urology Services in the ASC

Urology Services in the ASC Brad D. Lerner, MD, FACS, CASC Medical Director Summit ASC President of Chesapeake Urology Associates Chief of Urology Union Memorial Hospital Urologic Consultant NFL Baltimore Ravens Learning Objectives: Describe the numerous basic and advanced urology cases/lines of service that can be provided in an ASC setting Discuss various opportunities regarding clinical, operational and financial aspects of urology lines of service in an ASC setting Why Offer Urology Services in Your ASC? Majority of urologic surgical services are already outpatient Many urologic procedures are high volume, short duration and low cost Increasing emphasis on movement of site of service for surgical cases from hospitals and insurance carriers to ASCs There are still some case types where patients are traditionally admitted or placed in extended recovery status that can be converted to strictly outpatient status and would be suitable for an ASC Potential core of fee-for-service case types (microsurgery, aesthetics, prosthetics, etc.) Increasing Population of Those Aged 65 and Over As of 2018, it was estimated that there were 51 million persons aged 65 and over (15.63% of total population) By 2030, it is expected that there will be 72.1 million persons aged 65 and over National ASC Statistics - 2017 Urology cases represented 6% of total case mix for ASCs Urology cases were 4th in median net revenue per case (approximately $2,400) – behind Orthopedics, ENT and Podiatry Urology comprised 3% of single specialty ASCs (5th behind -

Clinical Significance of Cystoscopic Urethral Stricture

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title Clinical significance of cystoscopic urethral stricture recurrence after anterior urethroplasty: a multi-institution analysis from Trauma and Urologic Reconstructive Network of Surgeons (TURNS). Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3f57n621 Journal World journal of urology, 37(12) ISSN 0724-4983 Authors Baradaran, Nima Fergus, Kirkpatrick B Moses, Rachel A et al. Publication Date 2019-12-01 DOI 10.1007/s00345-019-02653-6 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California World Journal of Urology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-019-02653-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Clinical signifcance of cystoscopic urethral stricture recurrence after anterior urethroplasty: a multi‑institution analysis from Trauma and Urologic Reconstructive Network of Surgeons (TURNS) Nima Baradaran1 · Kirkpatrick B. Fergus2 · Rachel A. Moses3 · Darshan P. Patel3 · Thomas W. Gaither2 · Bryan B. Voelzke4 · Thomas G. Smith III5 · Bradley A. Erickson6 · Sean P. Elliott7 · Nejd F. Alsikaf8 · Alex J. Vanni9 · Jill Buckley10 · Lee C. Zhao11 · Jeremy B. Myers3 · Benjamin N. Breyer2 Received: 13 December 2018 / Accepted: 24 January 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose To assess the functional Queryoutcome of patients with cystoscopic recurrence of stricture post-urethroplasty and to evaluate the role of cystoscopy as initial screening tool to predict future failure. Methods Cases with cystoscopy data after anterior urethroplasty in a multi-institutional database were retrospectively studied. Based on cystoscopic evaluation, performed within 3-months post-urethroplasty, patients were categorized as small-caliber (SC) stricture recurrence: stricture unable to be passed by standard cystoscope, large-caliber (LC) stricture accommodating a cystoscope, and no recurrence. -

Surgical Treatment of Urinary Incontinence in Men

Committee 13 Surgical Treatment of Urinary Incontinence in Men Chairman S. HERSCHORN (Canada) Members H. BRUSCHINI (Brazil), C.COMITER (USA), P.G RISE (France), T. HANUS (Czech Republic), R. KIRSCHNER-HERMANNS (Germany) 1121 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION VIII. TRAUMATIC INJURIES OF THE URETHRA AND PELVIC FLOOR II. EVALUATION PRIOR TO SURGICAL THERAPY IX. CONTINUING PEDIATRIC III. INCONTINENCE AFTER RADICAL PROBLEMS INTO ADULTHOOD: THE PROSTATECTOMY FOR PROSTATE EXSTROPHY-EPISPADIAS COMPLEX CANCER X. DETRUSOR OVERACTIVITY AND IV. INCONTINENCE AFTER REDUCED BLADDER CAPACITY PROSTATECTOMY FOR BENIGN DISEASE XI. URETHROCUTANEOUS AND V. SURGERY FOR INCONTINENCE IN RECTOURETHRAL FISTULAE ELDERLY MEN VI. INCONTINENCE AFTER XII. THE ARTIFICIAL URINARY EXTERNAL BEAM RADIOTHERAPY SPHINCTER (AUS) ALONE AND IN COMBINATION WITH SURGERY FOR PROSTATE CANCER XIII. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS VII. INCONTINENCE AFTER OTHER TREATMENT FOR PROSTATE CANCER REFERENCES 1122 Surgical Treatment of Urinary Incontinence in Men S. HERSCHORN, H. BRUSCHINI, C. COMITER, P. GRISE, T. HANUS, R. KIRSCHNER-HERMANNS high-intensity focused ultrasound, other pelvic I. INTRODUCTION operations and trauma is a particularly challenging problem because of tissue damage outside the lower Surgery for male incontinence is an important aspect urinary tract. The artificial sphincter implant is the of treatment with the changing demographics of society most widely used surgical procedure but complications and the continuing large numbers of men undergoing may be more likely than in other areas and other surgery and other treatments for prostate cancer. surgical approaches may be necessary. Unresolved problems from pediatric age and patients with Basic evaluation of the patient is similar to other areas refractory incontinence from overactive bladders may of incontinence and includes primarily a clinical demand a variety of complex reconstructive surgical approach with history, frequency-volume chart or procedures. -

Thromboprophylaxis in Urological Surgery

EAU Guidelines on Thromboprophylaxis in Urological Surgery K.A.O. Tikkinen (Chair), R. Cartwright, M.K. Gould, R. Naspro, G. Novara, P.M. Sandset, P. D . Violette, G.H. Guyatt © European Association of Urology 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Aims and objectives 3 1.2 Panel composition 3 1.3 Available publications 3 1.4 Publication history 3 2. METHODS 3 2.1 Guideline methodology 3 3. GUIDELINE 4 3.1 Thromboprophylaxis post-surgery 4 3.1.1 Introduction 4 3.1.2 Outcomes and definitions 4 3.1.3 Timing and duration of thromboprophylaxis 4 3.1.4 Basic principles for recommending (or not recommending) post-surgery thromboprophylaxis 5 3.1.4.1 Effect of prophylaxis on key outcomes 5 3.1.4.2 Baseline risk of key outcomes 5 3.1.4.3 Patient-related risk (and protective) factors 5 3.1.4.4 From evidence to recommendations 6 3.1.5 General statements for all procedure-specific recommendations 7 3.1.6 Recommendations 7 3.2 Peri-operative management of antithrombotic agents in urology 14 3.2.1 Introduction 14 3.2.2 Evidence summary 14 3.2.3 Recommendations 14 4. RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS 16 5. REFERENCES 16 6. CONFLICT OF INTEREST 18 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 18 8. CITATION INFORMATION 18 2 THROMBOPROPHYLAXIS - MARCH 2017 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Aims and objectives Due to the hypercoagulable state induced by surgery, serious complications of urological surgery include deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) - together referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE) - and major bleeding [1-4]. -

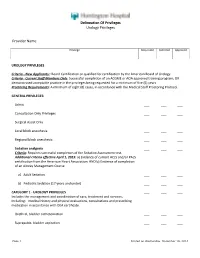

Delineation of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name

Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider Name: Privilege Requested Deferred Approved UROLOGY PRIVILEGES Criteria - New Applicants:: Board Certification or qualified for certification by the American Board of Urology. Criteria - Current Staff Members Only: Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA approved training program; OR demonstrated acceptable practice in the privileges being requested for a minimum of five (5) years. Proctoring Requirements: A minimum of eight (8) cases, in accordance with the Medical Staff Proctoring Protocol. GENERAL PRIVILEGES: Admit ___ ___ ___ Consultation Only Privileges ___ ___ ___ Surgical Assist Only ___ ___ ___ Local block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Regional block anesthesia ___ ___ ___ Sedation analgesia ___ ___ ___ Criteria: Requires successful completion of the Sedation Assessment test. Additional criteria effective April 1, 2015: a) Evidence of current ACLS and/or PALS certification from the American Heart Association; AND b) Evidence of completion of an Airway Management Course a) Adult Sedation ___ ___ ___ b) Pediatric Sedation (17 years and under) ___ ___ ___ CATEGORY 1 - UROLOGY PRIVILEGES ___ ___ ___ Includes the management and coordination of care, treatment and services, including: medical history and physical evaluations, consultations and prescribing medication in accordance with DEA certificate. Urethral, bladder catheterization ___ ___ ___ Suprapubic, bladder aspiration ___ ___ ___ Page 1 Printed on Wednesday, December 10, 2014 Delineation Of Privileges Urology Privileges Provider -

Effective Endoscopic Holmium Laser Lithotripsy in the Treatment of a Large

Cases and Techniques Library (CTL) E485 The patient was discharged after 15 days with complete resolution of the occlusive Effective endoscopic holmium laser lithotripsy symptoms, and her scheduled chole- in the treatment of a large impacted gallstone cystectomy was canceled. in the duodenum Endoscopy_UCTN_Code_CCL_1AZ_2AD Competing interests: None Fig. 1 Computed tomographic scan shows a large calcified Vincenzo Mirante, Helga Bertani, ring (stone) in the Giuseppe Grande, Mauro Manno, duodenum of an Angelo Caruso, Santi Mangiafico, 87-year-old woman Rita Conigliaro presenting with ab- U.O.C. Gastroenterology and Digestive dominal pain and vomiting of 3 days’ Endoscopy Unit, Nuovo Ospedale Civile duration. Sant'Agostino Estense, Modena, Italy References 1 Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a re- view of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg 1994; 60: 441–446 2 Rodriguez H, Codina C, Girones V et al. Gall- stone ileus: results of analysis of a series of Gallstone ileus is caused by the passage To fragment the stone, we performed an- 40 patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; – of one or more large gallstones (at least other endoscopic procedure. A holmium 24: 489 494 3 Rigler LG, Borman CN, Noble JF. Gallstone ob- 2.5 cm in size) in the gastrointestinal tract laser (HLS30W Holmium:YAG 30W Laser; struction: pathogenesis and roentgen mani- through a bilioenteric fistula. It accounts Olympus America, Center Valley, Penn- festations. JAMA 1941; 117: 1753 –1759 for 1 % to 4% of all cases of mechanical sylvania, USA) was applied for a total of 4 Goldstein EB, Savel RH, Pachter HL et al. Suc- small-bowel obstruction [1,2]. -

A Systematic Review of Graft Augmentation Urethroplasty Techniques for the Treatment of Anterior Urethral Strictures

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 59 (2011) 797–814 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.europeanurology.com Review – Reconstructive Urology A Systematic Review of Graft Augmentation Urethroplasty Techniques for the Treatment of Anterior Urethral Strictures Altaf Mangera *, Jacob M. Patterson, Christopher R. Chapple Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, United Kingdom Article info Abstract Article history: Context: Reconstructive surgeons who perform urethroplasty have a variety of Accepted February 2, 2011 techniques in their armamentarium that may be used according to factors such as Published online ahead of aetiology, stricture position, and length. No one technique is recommended. print on February 11, 2011 Objective: Our aim was to assess the reported outcomes of the various techniques for graft augmentation urethroplasty according to site of surgery. Keywords: Evidence acquisition: We performed an updated systematic review of the Medline Augmentation urethroplasty literature from 1985 to date and classified the data according to the site of surgery Anterior urethral stricture and technique used. Data are also presented on the type of graft used and the Bulbar urethroplasty follow-up methodology used by each centre. Dorsal onlay bulbar Evidence synthesis: More than 2000 anterior urethroplasty procedures have been urethroplasty describedinthe literature.Whenconsidering the bulbar urethra there isnosignificant Ventral onlay bulbar difference between the average success rates of the dorsal and the ventral onlay urethroplasty procedures, 88.4% and 88.8% at42.2 and 34.4 moin 934 and 563 patients,respectively. Penile urethroplasty The lateral onlay technique has only been described in six patients and has a reported success rate of 83% at 77 mo. The Asopa and Palminteri techniques have been described in 89 and 53 patients with a success rate of 86.7% and 90.1% at 28.9 and 21.9 mo, respectively. -

Efficacy of Revision Urethroplasty in the Treatment Of

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Bali Medical Journal (Bali Med J) 2020, Volume 9, Number 1: 67-76 P-ISSN.2089-1180, E-ISSN.2302-2914 Efficacy of revision urethroplasty in the treatment of ORIGINAL ARTICLE recurrent urethral strictures at a tertiary hospital (Kenyatta National Hospital–KNH), in Nairobi Kenya: Published by DiscoverSys CrossMark Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15562/bmj.v9i1.1675 2015-2018 Willy H. Otele,* Sammy Miima, Francis Owilla, Simeon Monda Volume No.: 9 ABSTRACT Issue: 1 Background: Urethral strictures cause malfunction of the urethra. while Subsidiary outcome measures were associated complications. Urethroplasty is a cost-effective treatment option. Its success rate Outcomes were compared using statistical package SPSS version 23.0. is greater than 90% where excision and primary anastomosis(EPA) Result: 235 patients who met inclusion criteria underwent is performed and 80-85% following substitution urethroplasty. urethroplasty, 71.5% (n=168) had a successful outcome, while28.5% First page No.: 67 Definitive treatment for recurrent urethral strictures after (n=67) failed and were subjected to revision urethroplasty. Another urethroplasty is not defined. Repeat urethroplasty is a viable option 58% were successful upon revision but experienced significant with unknown efficacy. morbidity. Majority of urethral strictures were bulbomembranous. P-ISSN.2089-1180 Method: Retrospective analysis of patients who underwent revision Trauma was the leading cause of urethral strictures followed by urethroplasty for unsuccessful urethroplasty at KNH from 2015 to idiopathic strictures. EPA was the commonest surgery while Tissue 2018 was performed. Patients’ age, demographic data, stricture transfer featured prominently in revision urethroplasty. A significant length, location, aetiology, comorbidities and type of urethroplasty correlation was evident between stricture length, prior surgery, and E-ISSN.2302-2914 was evaluated from records with complete data. -

Cystectomy and Neo Bladder Surgery

Form: D-5379 Cystectomy and Neo Bladder Surgery A guide for patients and families Reading this booklet can help you prepare for your surgery, hospital stay and recovery after surgery. We encourage you to take an active role in your care. If you have any questions, please ask a member of your health care team. Inside this booklet page Learning about your surgery ...................................................3 Preparing for surgery ...............................................................5 Your hospital stay ......................................................................9 Getting ready to leave the hospital .........................................17 Your recovery after surgery .....................................................19 Who to call if you have questions ............................................29 When to get medical help ........................................................30 2 Learning about your surgery What is a Cystectomy? Cystectomy is surgery to remove your bladder. This is usually done to control bladder cancer. Depending on the extent of the cancer, the bladder and some surrounding organs may need to be removed. • The prostate gland, seminal vesicles and nerve bundles may also be removed. • The ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and part of the vagina may also be removed. What is a Neo Bladder? Words to know A neo bladder is a pouch made from a Neo means new. piece of your bowel that is placed where A neo bladder is a new bladder. your bladder was removed. A neo bladder is commonly called a pouch, because a piece The pouch acts like a bladder, collecting of your bowel is made into a urine that comes down the ureters from pouch that can store urine. the kidneys. When you pass urine, it The medical name for this is a leaves the pouch through your urethra. -

Comparison of Postoperative Renal Function Between Non-Steroidal

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Comparison of Postoperative Renal Function between Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug and Opioids for Patient-Controlled Analgesia after Laparoscopic Nephrectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study Jiwon Han 1 , Young-Tae Jeon 1,2, Ah-Young Oh 1,2 , Chang-Hoon Koo 1, Yu Kyung Bae 1 and Jung-Hee Ryu 1,2,* 1 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, 82, Gumi-ro, Bundang-gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do 13620, Korea; [email protected] (J.H.); [email protected] (Y.-T.J.); [email protected] (A.-Y.O.); [email protected] (C.-H.K.); [email protected] (Y.K.B.) 2 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 103, Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-31-787-7497 Received: 7 August 2020; Accepted: 9 September 2020; Published: 13 September 2020 Abstract: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used as opioid alternatives for patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). However, their use after nephrectomy has raised concerns regarding possible nephrotoxicity. This study compared postoperative renal function and postoperative outcomes between patients using NSAID and patients using opioids for PCA in nephrectomy. In this retrospective observational study, records were reviewed for 913 patients who underwent laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy from 2015 to 2017. After propensity score matching, 247 patients per group were analyzed. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) percentages (postoperative value divided by preoperative value), blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/creatinine ratios, and serum creatinine percentages were compared at 2 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year after surgery between users of NSAID and users of opioids for PCA. -

And Ventral Buccal Mucosal Onlay (7 Days) Urethroplasty

Clinical Urology EARLY CATHETER REMOVAL AFTER URETHROPLASTY International Braz J Urol Vol. 31 (5): 459-464, September - October, 2005 Official Journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology EARLY CATHETER REMOVAL AFTER ANTERIOR ANASTOMOTIC (3 DAYS) AND VENTRAL BUCCAL MUCOSAL ONLAY (7 DAYS) URETHROPLASTY HOSAM S. AL-QUDAH, ANDRE G. CAVALCANTI, RICHARD A. SANTUCCI Department of Urology (HSAQ, RAS), Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan, USA, and Section of Urology (AGC), Souza Aguiar Municipal Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil ABSTRACT Introduction: Physicians who perform urethroplasty have varying opinions about when the urinary catheter should be removed post-operatively, but research on this subject has not yet appeared in the literature. We performed voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) on our anterior urethroplasty pa- tients on days 3 (anastomotic) and 7 (buccal) in an effort to determine the earliest day for removal of the urethral catheter. Materials and Methods: Retrospective chart review of 29 urethroplasty patients from Octo- ber 2002 - August 2004 was performed at two reconstructive urology centers. 17 patients had early catheter removal (12 anastomotic and 5 ventral buccal onlay urethroplasty) and were compared to 12 who had late removal (7 anastomotic and 5 buccal). Results: Of those with early catheter removal, 2/12 (17%) of anastomotic urethroplasty pa- tients had extravasation, which resolved by the following week and 0/5 (0%) of the buccal mucosal urethroplasty patients had extravasation. Patients with late catheter removal underwent VCUG 6-14 days (mean 8 days) after anastomotic urethroplasty and 9-14 days (mean 12 days) after buccal mu- cosal urethroplasty. 0% of the anastomotic urethroplasty had leakage after the late VCUG and 1/5 (20%) of the buccal patients had extravasation after the VCUG.