Thromboprophylaxis in Urological Surgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bris Or Brit Milah (Ritual Circumcision) According to Jewish Law, a Healthy Baby Boy Is Circumcised on the Eighth Day After His Birth

Bris or Brit milah (ritual circumcision) According to Jewish law, a healthy baby boy is circumcised on the eighth day after his birth. The brit milah, the ritual ceremony of removing the foreskin which covers the glans of the penis, is a simple surgical procedure that can take place in the home or synagogue and marks the identification of a baby boy as a Jew. The ceremony is traditionally conducted by a mohel, a highly trained and skilled individual, although a rabbi in conjunction with a physician may perform the brit milah. The brit milah is a joyous occasion for the parents, relatives and friends who celebrate in this momentous event. At the brit milah, it is customary to appoint a kvater (a man) and a kvaterin (a woman), the equivalent of Jewish godparents, whose ritual role is to bring the child into the room for the circumcision. Another honor bestowed on a family member is the sandak, who is most often the baby’s paternal grandfather or great-grandfather. This individual traditionally holds the baby during the circumcision ceremony. The service involves a kiddush (prayer over wine), the circumcision, blessings, a dvar torah (a small teaching of the Torah) and the presentation of the Jewish name selected for the baby. During the brit milah, a chair is set aside for Elijah the prophet. Following the ceremony, a seudat mitzvah (celebratory meal) is available for the guests. Please take note: Formal invitations for a bris are not sent out. Typically, guests are notified by phone or email. The baby’s name is not given before the bris. -

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S

Guidelines on Paediatric Urology S. Tekgül (Chair), H.S. Dogan, E. Erdem (Guidelines Associate), P. Hoebeke, R. Ko˘cvara, J.M. Nijman (Vice-chair), C. Radmayr, M.S. Silay (Guidelines Associate), R. Stein, S. Undre (Guidelines Associate) European Society for Paediatric Urology © European Association of Urology 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Aim 7 1.2 Publication history 7 2. METHODS 8 3. THE GUIDELINE 8 3A PHIMOSIS 8 3A.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 8 3A.2 Classification systems 8 3A.3 Diagnostic evaluation 8 3A.4 Disease management 8 3A.5 Follow-up 9 3A.6 Conclusions and recommendations on phimosis 9 3B CRYPTORCHIDISM 9 3B.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 9 3B.2 Classification systems 9 3B.3 Diagnostic evaluation 10 3B.4 Disease management 10 3B.4.1 Medical therapy 10 3B.4.2 Surgery 10 3B.5 Follow-up 11 3B.6 Recommendations for cryptorchidism 11 3C HYDROCELE 12 3C.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 12 3C.2 Diagnostic evaluation 12 3C.3 Disease management 12 3C.4 Recommendations for the management of hydrocele 12 3D ACUTE SCROTUM IN CHILDREN 13 3D.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology 13 3D.2 Diagnostic evaluation 13 3D.3 Disease management 14 3D.3.1 Epididymitis 14 3D.3.2 Testicular torsion 14 3D.3.3 Surgical treatment 14 3D.4 Follow-up 14 3D.4.1 Fertility 14 3D.4.2 Subfertility 14 3D.4.3 Androgen levels 15 3D.4.4 Testicular cancer 15 3D.5 Recommendations for the treatment of acute scrotum in children 15 3E HYPOSPADIAS 15 3E.1 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology -

IS CIRCUMCISION a FRAUD? FRAUD? a IS CIRCUMCISION Peter W

cjp_30-1_42664 Sheet No. 27 Side A 11/12/2020 09:05:36 \\jciprod01\productn\C\CJP\30-1\CJP102.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-NOV-20 14:50 IS CIRCUMCISION A FRAUD? Peter W. Adler, Robert Van Howe, Travis Wisdom & Felix Daase* This Article suggests that non-therapeutic male circumcision or male genital cutting (MGC), the irreversible removal of the foreskin from the penises of healthy boys, is not only unlawful in the United States but also fraudulent. As a German court held in 2012 before its ruling was effectively overturned by a special statute under political pressure, cir- cumcision for religious or non-medical reasons is harmful, violates the child’s rights to bodily integrity and self-determination (which super- sedes competing parental rights), and constitutes criminal assault. MGC also violates the child’s rights under U.S. law, and it constitutes a bat- tery, a tort and a crime, and statutory child abuse. Building upon a 2016 case in the United Kingdom, we make the novel suggestion that when performed by a physician, MGC is a breach of trust or fiduciary duty, and hence constructive fraud, where courts impute fraud even if intent to defraud is absent. We reprise and build upon the argument that it is unlawful and Medicaid fraud for physicians and hospitals to bill Medi- caid for unnecessary genital surgery. Finally, we suggest that MGC con- stitutes intentional fraud by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and most physicians who perform circumcisions in the United States. They have long portrayed MGC as medicine when it is violence, and as a parental right when males have the right to keep their penile foreskin, and physicians are not allowed to take orders from parents to perform cjp_30-1_42664 Sheet No. -

The Human Foreskin the Foreskin Is Not an Optional Extra for a Man’S Body, Or an Accident

The Human Foreskin The foreskin is not an optional extra for a man’s body, or an accident. It is an integral, functioning, important component of a man’s penis. An eye does not function properly without an eyelid – and nor does a penis without its foreskin. Among other things, the foreskin provides: Protection The foreskin fully covers the glans (head) of the flaccid penis, thereby protecting it from damage and harsh rubbing against abrasive agents (underwear, etc.) and maintaining its sensitivity Sexual Sensitivity The foreskin provides direct sexual pleasure in its own right, as it contains the highest concentration of nerve endings on the penis Lubrication The foreskin, with its unique mucous membrane, permanently lubricates the glans, thus improving sensitivity and aiding smoother intercourse Skin-Gliding During Erection The foreskin facilitates the gliding movement of the skin of the penis up and down the penile shaft and over the glans during erection and sexual activity Varied Sexual Sensation The foreskin facilitates direct stimulation of the glans during sexual activity by its interactive contact with the sensitive glans Immunological Defense The foreskin helps clean and protect the glans via the secretion of anti-bacterial agents What circumcision takes away The foreskin is at the heart of male sexuality. Circumcision almost always results in a diminution of sexual sensitivity; largely because removing the foreskin cuts away the most nerve-rich part of the penis (up to 80% of the penis’s nerve endings reside in the foreskin) [1]. The following anatomy is amputated with circumcision: The Taylor “ridged band” (sometimes called the “frenar band”), the primary erogenous zone of the male body. -

Effective Endoscopic Holmium Laser Lithotripsy in the Treatment of a Large

Cases and Techniques Library (CTL) E485 The patient was discharged after 15 days with complete resolution of the occlusive Effective endoscopic holmium laser lithotripsy symptoms, and her scheduled chole- in the treatment of a large impacted gallstone cystectomy was canceled. in the duodenum Endoscopy_UCTN_Code_CCL_1AZ_2AD Competing interests: None Fig. 1 Computed tomographic scan shows a large calcified Vincenzo Mirante, Helga Bertani, ring (stone) in the Giuseppe Grande, Mauro Manno, duodenum of an Angelo Caruso, Santi Mangiafico, 87-year-old woman Rita Conigliaro presenting with ab- U.O.C. Gastroenterology and Digestive dominal pain and vomiting of 3 days’ Endoscopy Unit, Nuovo Ospedale Civile duration. Sant'Agostino Estense, Modena, Italy References 1 Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a re- view of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg 1994; 60: 441–446 2 Rodriguez H, Codina C, Girones V et al. Gall- stone ileus: results of analysis of a series of Gallstone ileus is caused by the passage To fragment the stone, we performed an- 40 patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; – of one or more large gallstones (at least other endoscopic procedure. A holmium 24: 489 494 3 Rigler LG, Borman CN, Noble JF. Gallstone ob- 2.5 cm in size) in the gastrointestinal tract laser (HLS30W Holmium:YAG 30W Laser; struction: pathogenesis and roentgen mani- through a bilioenteric fistula. It accounts Olympus America, Center Valley, Penn- festations. JAMA 1941; 117: 1753 –1759 for 1 % to 4% of all cases of mechanical sylvania, USA) was applied for a total of 4 Goldstein EB, Savel RH, Pachter HL et al. Suc- small-bowel obstruction [1,2]. -

The Circumcision Decision

The Circumcision Decision Circumcision is a surgical procedure in which the skin covering the end of the penis is removed. Scientific studies show a number of medical benefits to circumcision. Parents may also want their son circumcised for religious, social or cultural reasons. Because circumcision is not essential to a child’s health, parents should choose what is best for their child by looking at the benefits, the risks and discussing it with their pediatrician. The following are answers to common questions about circumcision. What Is Circumcision? What Should I Expect For My Son After Circumcision? At birth, boys have skin that covers the end of the penis, called the foreskin. After the circumcision, the tip of the penis Circumcision surgically removes the may seem raw or yellowish. The diaper foreskin, exposing the tip of the penis. should be applied loosely and changed Circumcision is usually performed by a frequently for the first few days. This doctor in the first few days of life. An will help prevent possible infection and infant must be stable and healthy to safely keep the penis from becoming irritated. be circumcised. Petroleum jelly may be used to keep the healing penis from sticking to the Because circumcision may be more risky diaper. Surgical gauze is often applied if done later in life, parents should decide after completion of the circumcision to before or soon after their son is born if prevent bleeding. The gauze will fall off they want it done. on its own in a few days. The penis should be fully healed in about 7-10 days after Is Circumcision Painful? circumcision. -

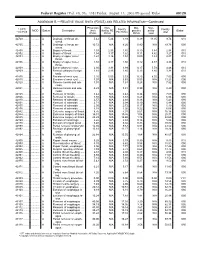

RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) and RELATED INFORMATION—Continued

Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 158 / Friday, August 15, 2003 / Proposed Rules 49129 ADDENDUM B.—RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND RELATED INFORMATION—Continued Physician Non- Mal- Non- 1 CPT/ Facility Facility 2 MOD Status Description work facility PE practice acility Global HCPCS RVUs RVUs PE RVUs RVUs total total 42720 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 5.42 5.24 3.93 0.39 11.05 9.74 010 scess. 42725 ....... ........... A Drainage of throat ab- 10.72 N/A 8.26 0.80 N/A 19.78 090 scess. 42800 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.39 2.35 1.45 0.10 3.84 2.94 010 42802 ....... ........... A Biopsy of throat ................ 1.54 3.17 1.62 0.11 4.82 3.27 010 42804 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.24 3.16 1.54 0.09 4.49 2.87 010 throat. 42806 ....... ........... A Biopsy of upper nose/ 1.58 3.17 1.66 0.12 4.87 3.36 010 throat. 42808 ....... ........... A Excise pharynx lesion ...... 2.30 3.31 1.99 0.17 5.78 4.46 010 42809 ....... ........... A Remove pharynx foreign 1.81 2.46 1.40 0.13 4.40 3.34 010 body. 42810 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 3.25 5.05 3.53 0.25 8.55 7.03 090 42815 ....... ........... A Excision of neck cyst ........ 7.07 N/A 5.63 0.53 N/A 13.23 090 42820 ....... ........... A Remove tonsils and ade- 3.91 N/A 3.63 0.28 N/A 7.82 090 noids. -

Cystectomy and Neo Bladder Surgery

Form: D-5379 Cystectomy and Neo Bladder Surgery A guide for patients and families Reading this booklet can help you prepare for your surgery, hospital stay and recovery after surgery. We encourage you to take an active role in your care. If you have any questions, please ask a member of your health care team. Inside this booklet page Learning about your surgery ...................................................3 Preparing for surgery ...............................................................5 Your hospital stay ......................................................................9 Getting ready to leave the hospital .........................................17 Your recovery after surgery .....................................................19 Who to call if you have questions ............................................29 When to get medical help ........................................................30 2 Learning about your surgery What is a Cystectomy? Cystectomy is surgery to remove your bladder. This is usually done to control bladder cancer. Depending on the extent of the cancer, the bladder and some surrounding organs may need to be removed. • The prostate gland, seminal vesicles and nerve bundles may also be removed. • The ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and part of the vagina may also be removed. What is a Neo Bladder? Words to know A neo bladder is a pouch made from a Neo means new. piece of your bowel that is placed where A neo bladder is a new bladder. your bladder was removed. A neo bladder is commonly called a pouch, because a piece The pouch acts like a bladder, collecting of your bowel is made into a urine that comes down the ureters from pouch that can store urine. the kidneys. When you pass urine, it The medical name for this is a leaves the pouch through your urethra. -

Comparison of Postoperative Renal Function Between Non-Steroidal

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Comparison of Postoperative Renal Function between Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug and Opioids for Patient-Controlled Analgesia after Laparoscopic Nephrectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study Jiwon Han 1 , Young-Tae Jeon 1,2, Ah-Young Oh 1,2 , Chang-Hoon Koo 1, Yu Kyung Bae 1 and Jung-Hee Ryu 1,2,* 1 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, 82, Gumi-ro, Bundang-gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do 13620, Korea; [email protected] (J.H.); [email protected] (Y.-T.J.); [email protected] (A.-Y.O.); [email protected] (C.-H.K.); [email protected] (Y.K.B.) 2 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 103, Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-31-787-7497 Received: 7 August 2020; Accepted: 9 September 2020; Published: 13 September 2020 Abstract: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used as opioid alternatives for patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). However, their use after nephrectomy has raised concerns regarding possible nephrotoxicity. This study compared postoperative renal function and postoperative outcomes between patients using NSAID and patients using opioids for PCA in nephrectomy. In this retrospective observational study, records were reviewed for 913 patients who underwent laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy from 2015 to 2017. After propensity score matching, 247 patients per group were analyzed. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) percentages (postoperative value divided by preoperative value), blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/creatinine ratios, and serum creatinine percentages were compared at 2 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year after surgery between users of NSAID and users of opioids for PCA. -

The Effect of Circumcision on the Mental Health of Children: a Review •

Turkish Journal of Psychiatry 2012 Th e Eff ect of Circumcision on the Mental Health of Children: A Review • Mesut YAVUZ1, Türkay DEMİR2, Burak DOĞANGÜN2 SUMMARY Circumcision is one of the oldest and most frequently performed surgical procedures in the world. It is thought that the beginning of the male circumcision dates back to the earliest times of history. Approximately 13.3 million boys and 2 million girls undergo circumcision each year. In western societies, circumcision is usually performed in infancy while in other parts of the world, it is performed at different developmental stages. Each year in Turkey, especially during the summer months, thousands of children undergo circumcision. The motivations for circumcision include medical-therapeutic, preventive-hygienic and cultural reasons. Numerous publications have suggested that circumcision has serious traumatic ef- fects on children’s mental health. Studies conducted in Turkey draw attention to the positive meanings attributed to the circumcision in the com- munity and emphasize that social effects limit the negative effects of circumcision. Although there are many publications in foreign literature about the mental effects of the circumcision on children’s mental health, there are only a few studies in Turkey about the mental effects of the one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures in our country. The aim of this study is to review this issue. The articles related to circumcision were searched by keywords in Pubmed, Medline, EBSCHOHost, PsycINFO, Turkish Medline, Cukurova Index Database and in Google Scholar and those appropriate for this review were used by authors. Key Words: Circumcision, child, mental health, psychology, trauma INTRODUCTION the Pacific (WHO 2006). -

(Part 1): Management of Male Urethral Stricture Disease

EURURO-9412; No. of Pages 11 E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y X X X ( 2 0 2 1 ) X X X – X X X ava ilable at www.sciencedirect.com journa l homepage: www.europeanurology.com Review – Reconstructive Urology European Association of Urology Guidelines on Urethral Stricture Disease (Part 1): Management of Male Urethral Stricture Disease a, b c d Nicolaas Lumen *, Felix Campos-Juanatey , Tamsin Greenwell , Francisco E. Martins , e f a c g Nadir I. Osman , Silke Riechardt , Marjan Waterloos , Rachel Barratt , Garson Chan , h i a j Francesco Esperto , Achilles Ploumidis , Wesley Verla , Konstantinos Dimitropoulos a b Division of Urology, Gent University Hospital, Gent, Belgium; Urology Department, Marques de Valdecilla University Hospital, Santander, Spain; c d Department of Urology, University College London Hospital, London, UK; Department of Urology, Santa Maria University Hospital, University of Lisbon, e f Lisbon, Portugal; Department of Urology, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK; Department of Urology, University Medical Center Hamburg- g h Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany; Division of Urology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada; Department of Urology, Campus Biomedico i j University of Rome, Rome, Italy; Department of Urology, Athens Medical Centre, Athens, Greece; Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, UK Article info Abstract Article history: Objective: To present a summary of the 2021 version of the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on management of male urethral stricture disease. Accepted May 15, 2021 Evidence acquisition: The panel performed a literature review on these topics covering a time frame between 2008 and 2018, and used predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria Associate Editor: for the literature to be selected. -

Infectious and Inflammatory Complications (IIC) in Patients

e3640 European Urology Supplements 18 (12), (2019), e3621–e3646 pediatric patients; moreover, we did not find literature with the results GUA-46 Choice of the method of draining the urinary tract of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) use. in residual stones after percutaneous Materials and methods: From January 2015 to November 2018 ESWL nephrolithomy in children was performed on an emergency basis to 124 children with renal colic which could not be treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory Y. S. Nadjimitdinov, Sh. T. Mukhtarov, Sh. Abbosov drugs or recurred repeatedly during 24 hours. Mean age was 9.5 ± 1.6, – Tashkent Medical Academy, Department of Urology, Tashkent, 83 were boys and 41 girls. Intravenous urography was done only in Uzbekistan the cases when there were doubts in stone size and level of its situation according to the plain urography. Before ESWL children’s parents were informed about the method and its complications and possible Background: To date, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNLT) is the manipulations in the urinary tract if necessary (ureteral stenting, method of choice in patients with urolithiasis. This method has proven endoscopic removal of stone fragments) or repeated lithotripsy. to be completely safe and effective in treating children with Results: Ambulant help was rendered to 21 patients; 103 patients nephrolithiasis. However, in some cases, for various reasons, it is not were hospitalized for 1 day. Stone size more than 10 mm (mean size possible using the endoscopic method to completely rid the patient of 14.2 ± 0.8 mm) was revealed in 48 patients. In 76 cases maximum calculi located in the kidney cavities.