Richard Wilson Slipstream.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative : a Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative: A Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand Soldier David Guerin 94114985 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand (Cover) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). (Above) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 2/1498, New Zealand Field Artillery, First New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 1915, left, & 1917, right. 2 Dedication Dedicated to: Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 1893 ̶ 1962, 2/1498, NZFA, 1NZEF; Alexander John McKay Manson, 11/1642, MC, MiD, 1895 ̶ 1975; John Guerin, 1889 ̶ 1918, 57069, Canterbury Regiment; and Christopher Michael Guerin, 1957 ̶ 2006; And all they stood for. Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). 3 Acknowledgements Distinguished Professor Sally J. Morgan and Professor Kingsley Baird, thesis supervisors, for their perseverance and perspicacity, their vigilance and, most of all, their patience. With gratitude and untold thanks. All my fellow PhD candidates and staff at Whiti o Rehua/School of Arts, and Toi Rauwhārangi/ College of Creative Arts, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa o Pukeahu Whanganui-a- Tara/Massey University, Wellington, especially Jess Richards. -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally. -

Ecological Consequences Artificial Night Lighting

Rich Longcore ECOLOGY Advance praise for Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting E c Ecological Consequences “As a kid, I spent many a night under streetlamps looking for toads and bugs, or o l simply watching the bats. The two dozen experts who wrote this text still do. This o of isis aa definitive,definitive, readable,readable, comprehensivecomprehensive reviewreview ofof howhow artificialartificial nightnight lightinglighting affectsaffects g animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of i animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of c Artificial Night Lighting photopollution, illustrated with important examples of how to mitigate these effects a on species ranging from sea turtles to moths. Each section is introduced by a l delightful vignette that sends you rushing back to your own nighttime adventures, C be they chasing fireflies or grabbing frogs.” o n —JOHN M. MARZLUFF,, DenmanDenman ProfessorProfessor ofof SustainableSustainable ResourceResource Sciences,Sciences, s College of Forest Resources, University of Washington e q “This book is that rare phenomenon, one that provides us with a unique, relevant, and u seminal contribution to our knowledge, examining the physiological, behavioral, e n reproductive, community,community, and other ecological effectseffects of light pollution. It will c enhance our ability to mitigate this ominous envirenvironmentalonmental alteration thrthroughough mormoree e conscious and effective design of the built environment.” -

Venturing in the Slipstream

VENTURING IN THE SLIPSTREAM THE PLACES OF VAN MORRISON’S SONGWRITING Geoff Munns BA, MLitt, MEd (hons), PhD (University of New England) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Western Sydney University, October 2019. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................. Geoff Munns ii Abstract This thesis explores the use of place in Van Morrison’s songwriting. The central argument is that he employs place in many of his songs at lyrical and musical levels, and that this use of place as a poetic and aural device both defines and distinguishes his work. This argument is widely supported by Van Morrison scholars and critics. The main research question is: What are the ways that Van Morrison employs the concept of place to explore the wider themes of his writing across his career from 1965 onwards? This question was reached from a critical analysis of Van Morrison’s songs and recordings. A position was taken up in the study that the songwriter’s lyrics might be closely read and appreciated as song texts, and this reading could offer important insights into the scope of his life and work as a songwriter. The analysis is best described as an analytical and interpretive approach, involving a simultaneous reading and listening to each song and examining them as speech acts. -

FURTHEST from I Anthony S

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 2009 FURTHEST FROM I Anthony S. Gurriero Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Gurriero, Anthony S., "FURTHEST FROM I" (2009). All NMU Master's Theses. 400. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/400 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. FURTHEST FROM I By Anthony S. Guerriero THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Graduate Studies Office 2009 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM This thesis by Anthony S. Guerriero is recommended for approval by the student’s Thesis Committee and Department Head in the Department of English and by the Associate Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies. ____________________________________________________________ Committee Chair: Dr. Ronald Johnson Date ____________________________________________________________ First Reader: Dr. Carol Bays Date ____________________________________________________________ Second Reader: Dr. John Smolens Date ____________________________________________________________ Department Head: Dr. Raymond J. Ventre Date ____________________________________________________________ Associate Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies: Date Dr. Cynthia Prosen OLSON LIBRARY NORTHERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY THESIS DATA FORM In order to catalog your thesis properly and enter a record in the OCLC international bibliographic data base, Olson Library must have the following requested information to distinguish you from other with the same or similar names and to provide appropriate subject access for other researchers. -

JETHRO TULL Aqualung

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] JETHRO TULL Aqualung The 45th Anniversary Edition Repack Das vierte JETHRO TULL-Album in der überarbeiteten Jubiläumsedition auf 2 CDs/2DVDs mit zusätzlichen Songs, der EP Life Is A Long Song, einem Promo- Video von 1971 und allen Tracks in mehreren audiophilen Formaten! VÖ: 22. April! Ein geifernder alter Mann mit langen Haaren und in einem verdreckten Mantel steht an einer Straßenecke und sieht JETHRO TULL-Frontmann Ian Anderson erstaunlich ähnlich. Auf ihrem vierten Album bewiesen JETHRO TULL nicht nur einen kritischen Blick auf die Menschen, die Religion und andere fundamentale Themen, sie ließen mit dem legendären Cover durchaus auch ihren Sinn für Humor und Ironie durchblicken. Im März 1971 erschien Aqualung, eines der besten und legendärsten Alben der TULL, das sich über 7 Millionen Mal verkaufte und in Deutschland seinerzeit Platz 5 der Albumcharts erreichte. Neben dem Titelsong findet man auf dem Album auch die Single Hymn 43 und den Track Locomotive Breath, der zu den größten Erfolgen der Band zählt. Oftmals als „Konzeptalbum“ eingeschätzt (dem die Band selbst stets widersprach) bildete Aqualung den Übergang vom Song-orientierten Benefit zu den Prog-Rockigen Alben Thick as A Brick (1972) und A Passion Play (1973). Tatsächlich besitzen die Songs auf Aqualung einen thematischen Zusammenhang und weisen diverse interreferenzielle Bezüge auf. Es ist das erste Album mit Bassist Jeffrey Hammond und Keyboarder John Evan als festes Mitglied sowie das letzte JETHRO TULL- Album mit Drummer Clive Bunker. Produziert wurde es von Sänger und Flötist Ian Anderson und Terry Ellis. -

Note Where Company Not Shown Separately, There

Note Where company not shown separately, there are identified against the 'item' Where a value is not shown, this is due to the nature of the item e.g. 'event' Date Post Company Item Value Status 27/01/2010 Director General Finance & Corproate Services Cardiff Council & Welsh Assembly Government Invitation to attend Holocaust Memorial Day declined 08/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Welsh Assembly Government Retirement Seminar - Reception Below 20 accepted 12/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Clwb Cinio Cymraeg Caerdydd Dinner Below 20 accepted 14/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Clwb Cymrodorion Caerdydd Reception Below 20 accepted Sir Christopher Jenkins - ex Parliamentary 19/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Lunch at the Bear Hotel, Crickhowell Below 20 accepted Counsel 21/04/2010 Acting Deputy Director, Lifelong Learners & Providers Division CIPFA At Cardiff castle to recognise 125 years of CIPFA and opening of new office in Cardiff £50.00 Accepted 29/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel University of Glamorgan Buffet lunch - followed by Chair of the afternoon session Below 20 accepted 07/05/2010 Deputy Director, Engagement & Student Finance Division Student Finance Officers Wales Lunch provided during meeting £10.00 Accepted 13/05/2010 First Legislative Counsel Swiss Ambassador Reception at Mansion House, Cardiff Below 20 accepted 14/05/2010 First Legislative Counsel Ysgol y Gyfraith, Coleg Prifysgol Caerdydd Cinio canol dydd Below 20 accepted 20/05/2010 First Legislative Counsel Pwyllgor Cyfreithiol Eglwys yng Nghymru Te a bisgedi -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

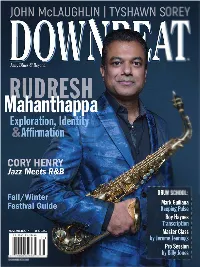

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

4539-Arcadegamelist.Pdf

1 005 80 3D_Tekken (WORLD) Ver. B 157 Alien Storm (Japan, 2 Players) 2 1 on 1 Government (Japan) 81 3D_Tekken <World ver.c> 158 Alien Storm (US,3 Players) 3 10 Yard Fight <Japan> 82 3D_Tekken 2 (JP) Ver. B 159 Alien Storm (World, 2 Players) 4 1000 Miglia:Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 83 3D_Tekken 2 (World) Ver. A 160 Alien Syndrome 5 10-Yard Fight ‘85 (US, Taito license) 84 3D_Tekken 2 <World ver.b> 161 Alien Syndrome (set 6, Japan, new) 6 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 85 3D_Tekken 3 (JP) Ver. A 162 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520 Phoenix Edition) 7 1941: Counter Attack (USA 900227) 86 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 163 Alien vs. Predator (Euro 940520) 8 1941:Counter Attack (World 900227) 87 3D_Tondemo Crisis 164 Alien vs. Predator (Hispanic 940520) 9 1942 (Revision B) 88 3D_Toshinden 2 165 Alien vs. Predator (Japan 940520) 10 1942 (Tecfri PCB, bootleg?) 89 3D_Xevious 3D/G (JP) Ver. A 166 Alien vs. Predator (USA 940520) 11 1943 Kai:Midway Kaisen (Japan) 90 3X3 Maze (Enterprise) 167 Alien3: The Gun (World) 12 1943: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 91 3X3 Maze (Normal) 168 Aliens <Japan> 13 1943:The Battle of Midway (Euro) 92 4 En Raya 169 Aliens <US> 14 1944: The Loop Master (USA Phoenix Edition) 93 4 Fun in 1 170 Aliens <World set 1> 15 1944:The Loop Master (USA 000620) 94 4-D Warriors 171 Aliens <World set 2> 16 1945 Part-2 (Chinese hack of Battle Garegga) 95 600 172 All American Football (rev D, 2 Players) 17 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) 96 64th. -

From Crop Duster to Airline; the Origins of Delta Air Lines to World War II

Roots: From Crop Duster to Airline; The Origins of Delta Air Lines to World War II by James John Hoogerwerf A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 13, 2010 Keywords: Delta Laboratory, Huff Daland, Delta Air Lines, B. R. Coad, Harold R. Harris, C.E. Woolman Copyright 2010 by James John Hoogerwerf Approved by William F. Trimble, Chair, Professor of History James R. Hansen, Professor of History Alan D. Meyer, Assistant Professor of History Tiffany A. Thomas, Assistant Professor of History Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of Dr. W. David Lewis Distinguished University Professor of History Auburn University (1931-2007) ii Abstract Delta Air Lines (Delta) is one of the great surviving legacy airlines of the first century of flight. In the annals of American aviation history its origins are unique. Delta’s beginning can be traced to the arrival of the boll weevil from Mexico into Texas in 1892. Unlike other national airlines that were nurtured on mail subsidies, Delta evolved from experiments using airplanes to counter the cotton weevil scourge from the air. The iconic book on the subject is Delta: The History of an Airline authored by two eminent Auburn University history professors, W. David Lewis and Wesley Phillips Newton. This dissertation explores more closely the circumstances and people involved in Delta’s early years up to World War II. It is chronologically organized and written in a narrative style. It argues Delta’s development was the result of a decades-long incremental and evolutionary process and not the calculated result of a grand design or the special insight of any one person. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least.