Old Stereotypes, New Myths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nixon, in France,11

SEE STORY BELOW Becoming Clear FINAL Clearing this afternoon. Fair and cold tonight. Sunny., mild- Red Bulk, Freehold EIMTION er tomorrow. I Long Branch . <S« SeUdlf, Pass 3} Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 173 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 1969 26 PAGES 10 CENTS ge Law Amendments Are Urged TRENTON - A legislative lative commission investigat- inate the requirement that where for some of die ser- the Monmouth Shore Refuse lection and disposal costs in Leader J. Edward CrabieJ, D- committee investigating the ing the garbage industry. there be unanimous consent vices tiie authority offers if Disposal Committee' hasn't its member municipalities, Middlesex, said some of the garbage industry yester- Mr. Gagliano called for among the participating the town wants to and the au- done any appreciable work referring the inquiry to the suggested changes were left day heard a request for amendments to the 1968 Solid municipalttes in the selection thority doesn't object. on the problems of garbage Monmouth County Planning out of the law specifically amendments to a 1968 law Waste Management Authority of a disposal site. He said the The prohibition on any par- collection "because we feel Board. last year because it was the permitting 21 Monmouth Saw, which permits the 21 committee might never ticipating municipality con- the disposal problem is funda- The Monmouth Shore Ref- only way to get the bill ap- County municipalities to form Monmouth County municipal- achieve unanimity on a site. tracting outside the authority mental, and we will get the use Disposal Committee will proved by both houses of the a regional garbage authority. -

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

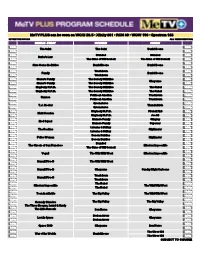

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

Bill Dana Collection

Thousand Oaks Library American Radio Archives Bill Dana Collection Bill Dana (1924- ), a comedian and actor, may be best known as "José Jiménez" a popular character he created on The Steve Allen Show in the 1950s and continued to perform throughout his career, but he is also a successful screenwriter, author, cartoonist, producer, director, recording artist, inventor and stand-up comedian. While Dana's own papers are at the American Comedy Archives at Emerson College (Boston, MA), a collection of TV scripts from the Aaron Spelling production company and a smaller number of radio scripts were transferred to the American Radio Archives. TV The Bill Dana Show No. Air Date Title Notes 1-01 09-22-1963 You Gotta Have Heart 1-02 09-29-1963 The Hypnotist 1-03 10-06-1963 Jose the Playboy 1-04 10-13-1963 Jose the Opera Singer (The Opera Singer) 1-05 10-27-1963 Jose the Stockholder 1-06 11-03-1963 The Bank Hold-up 1-07 11-10-1963 Honeymoon Suite 1-08 11-17-1963 Jose, the Agent 1-09 11-24-1963 The Poker Game 1-10 12-01-1963 Jose, the Astronaut (The Astronaut) 1-11 12-08-1963 Mr. Phillips' Watch 2 copies 1-12 12-29-1963 Beauty and the Baby (The Beauty and the Baby) 1-13 01-05-1964 Jose and the Brat (The Brat) 2 copies 1-14 01-12-1964 Jose's Dream Girl 1-16 01-26-1964 The Masquerade Party (Masquerade Party) 1-17 02-02-1964 Jose's Four Amigos 1-21 03-01-1964 Party in Suite 15 (The Party in Suite 15) 1-22 03-15-1964 Jose, the Matchmaker 1-23 03-22-1964 Jose's Hot Dog Caper (The Hot Dog Caper) 1-24 04-05-1964 The Hiring of Jose 1-25 04-19-1964 Master -

Monmouth County?S Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL 91, NO

Marlboro Denies Burnt Fly Dumping Variance \ SEE STORY BELOW Cloudy, Warm THEMILY FINAL Cloudy and warm today. Cloudy with showers likely to- Red Bank, Freehold EDITTGN night and again tomorrow. 7 Long Branch (See Details. Page S) Monmouth County?s Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL 91, NO. 208 RED BANK, N.J., FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 1969 28 PAGES 10 CENTS •••••••a Quiz Nixon on Plane WASHINGTON (AP) - naissance plane over the Sea ation the United States might contained fewer bristling deal to play down the epi- President Nixon faced his of Japan last Tuesday. make and how future recon- words than in past incidents. sode. first public questioning today The protest, delivered at a naissance flights would be When the USS Pueblo was The timing of the U.S. pro- over the loss of an American 42-minute meeting at the protected.. captured 15 months ago, the test at Panmunjom was Navy plane to North Korean Panmunjom truce site earlier Until today's news confer- Johnson administration called pushed on the administration jets with many points about today, was the first official ence, broadcast live by ra- the seizure a "heinous crime" when North Korea called for his policy still hidden behind U.S. reaction since the plane dio and television, Nixon him- committed by "North Ko- a meeting of the military ar- a curtain of official silence. was downed and the 31 crew- self had not spoken publicly rean gangsters." mistice commission, the Prior to his 11:30 a.m. men apparently lost. about the incident Administration sources sug- group which has met there news conference -

432 up 3.22 Home Front 1 Pm Dow-Jones, Helpful Hints Stocks Page 9A BOCA RATON NEWS Page IB Vol

200 23432 Up 3.22 Home Front 1 pm Dow-Jones, Helpful Hints Stocks page 9A BOCA RATON NEWS page IB Vol. 15, No. 128 Thursday, June 4, 1970 20 Pages 10 Cents Quiet bitterness growing among blacks WASHINGTON (UPI) — "Black Americans today are more bitter and The ghetto mood as summer approaches frustrated than ever before. The situation is very dangerous. The right levels, in all parts of the nation. From intentions, bitterly critical of the Nixon black rage is at an even higher pitch spark could set off racial violence in Harlem in the East to Watts in the administration, determined to gain now than it was in 1965"—the year in any city in the country." West, from Detroit in the North to equality by whatever means which the Watts section of Los Angeles Augusta in the South, I found them necessary. erupted in a week-long riot that cost 34 Those words were spoken by angry, resentful, cynical about white lives and more than $50 million in Thomas Bradley, a Negro city coun- The vast majority of blacks whom I property damage. interviewed oppose any repetition of cilman in Los Angeles. They sum- "There's a greater sense of bit- marize expressions of anxiety and the rioting that brought many U.S. cities to the brink of chaos during the terness now," said Lewis Robinson, despair that are widespread in the who helps manage a development black communities of the United 1960s. They don't see any future in LEWIS ROBINSON . burning down their neighborhoods. program in the Hough area of L.A. -

MF-V.00 Plus Pogtage. HC Not Available from EDRS

DOCUMENT, RESUME BD 126 850 IR 003 727 AUTHOR Heller, Melvin S.; Polsky, Samuel TITLE - Studies in 'Violence and Television. INSTITUTION American Broadcasting Co., New York, N.Y. REPORT NO LC-76-13572 PUB DATE 76 -*/ NOTE 529p.; fbir related documents, see IR 003 725 -727 EDRS PRICE MF-V.00 Plus Pogtage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adolescentsp Aggression; Anti Social Behavior; Broadcast Industry; *Children; Delinquents; Emotionally Disturbed-Children; Exceptional Children; Males; Media Research; Programing (Broadcast); Pro'social Behavior; *Research Reviews (Publications); Television Research; *Television Viewing; *Violence ABSTRACT The cd1plete reports of the research efforts on the effects of televised violence on children sponsored by the American Broadcasting Company in the past five years are presented. Ten research projects on aggression and violence are described which examined primarily the effect of television on children who were P emotionally disturbed, cane from broken homes,' or were juvenile offenders. In addition to complete documentation on each of the studies,'guAdelines for viewing and programing of televised violence are given. General implications for the broadcastingindustry in light of the findings of The studies are also included. Data collection instruments are appended. (HAB) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublish d *' * materials ndt available from other sources. ERIC makes everyof rt *. * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of margi 1 * *-reproducibility are often encountered and,this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERICImakes.avAilable *. * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * A * responsible for the quality of the original document.Reproductiops * * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from theoriginal. -

Television and Social Behavior; Reports and Papers, Volume I: Media Content and Control

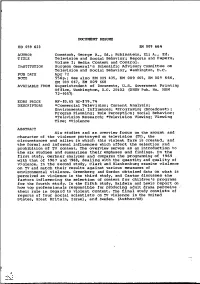

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 059 623 EM 009 664 AUTHOR Comstock, George A., Ed.; Rubinstein, Eli A., Ed. TITLE Television and Social Behavior; Reports and Papers, Volume I: Media Content and Control. INSTITUTION Surgeon General's Scientific Advisory Committee on Television and Social Behavior,Washington, D..C. PUB DATE Apr 72 NOTE 556p.; See also EM 009 435, EM009 665,EM009 666, EM 009 667, EM 009 668 AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Of fice, Washington, D.C. 20402(DHEW Pub. No. HSM 72-9057) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$19.74 DESCRIPTORS *Commercial Television; Content Analysis; Environmental Influences; *Programing (Broadcast) ; Program Planning; Role Perception; Social Behavior; *Television Research; *Television Viewing; Viewing Time; *Violence ABSTRACT Six studies and an overview focus on the amount and character of the violence portrayed on television (TV), the circumstances and milieu in which this violent fare is created, and the formal and informal influences which affect the selection and prohibition of TV content. The overview serves as an introduction to the six studies and summarizes their emphases and findings. In the first study, Gerbner analyzes and compares the programming of 1969 with that of 1967 and 1968, dealing with the quantity and quality of v3olence. In the second study, Clark and Blankenburg examine violence on TV and match their results against various measures of environmental violence. Greenberg and Gordon obtained data on what is perceived as violence in the third study, and Cantor discusses the factors influencing the selection of content for children's programs for the fourth study. In the fifth study, Baldwin and Lewis report on how top professionals responsible for producing adult drama perceive their role in regard to violent content. -

FJ4.1 Mingant

MINGANT FILM JOURNAL 4 (2017) Escaping Hollywood’s Arab acting ghetto: An Examination of the Career Patterns and Strategies of American Actors of Middle-Eastern Origin* Nolwenn MINGANT Université de Nantes The mid-2000s have been an ambiguous period for American actors of Middle-Eastern origins. Contradictory reports have appeared in the press, from the enthusiastic assertion that ‘‘It’s a good time to be an actor from the Middle East’’1 due to the growing number of American films dealing with the Middle East, to the description of the continued plight of actors ‘‘relegated to playing terrorists, the new Arab acting ghetto.’’2 One issue recurring in the few trade paper articles on the topic was indeed the difficulties encountered by these actors in a Hollywood context, where, in the words of Jack Shaheen, ‘‘There’s no escaping the Arab stereotype.’’3 The aim of this paper is to provide a specific case study on the career of these specific minority actors, thus participating to the larger debate on the place of minority personnel in Hollywood. Concurring with Ella Shohat, and Robert Stam’s remark that ‘‘(that) films are only representations does not prevent them from having real effects in the world,’’4 this paper will not call into question the idea of stereotypes but rather examine the very concrete consequences that these race-based stereotypes, bred both by the Hollywood industrial culture and by Mainstream America’s social imagination, have on employment opportunities for actors, and on the strategies available to escape these constraints. The basis of the article is the quantitative and qualitative analysis of a database mapping out the careers of 22 Arab-American and Iranian-American actors. -

Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. in Re

Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 12/29/2017 03:41:40 PM EST Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF THE MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS 2010-2013 SATELLITE ROYALTY YEARS VOLUME I OF II WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS Gregory O. Olaniran D.C. Bar No. 455784 Lucy Holmes Plovnick D.C. Bar No. 488752 Alesha M. Dominique D.C. Bar No. 990311 Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1818 N Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 355-7917 (Telephone) (202) 355-7887 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for MPAA-Represented Program Suppliers December 29, 2017 Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS FOR 2010-2013 SATELLITE ROYALTY YEARS The Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (“MPAA”), its member companies and other producers and/or distributors of syndicated series, movies, specials, and non-team sports broadcast by television stations who have agreed to representation by MPAA (“MPAA-represented Program Suppliers”),1 in accordance with the procedural schedule set forth in Appendix A to the December 22, 2017 Order Consolidating Proceedings And Reinstating Case Schedule issued by the Copyright Royalty Judges (“Judges”), hereby submit its Written Direct Statement Regarding Distribution Methodologies (“WDS-D”) for the 2010-2013 satellite royalty years2 in the consolidated 1 Lists of MPAA-represented Program Suppliers for each of the satellite royalty years at issue in this consolidated proceeding are included as Appendix A to the Written Direct Testimony of Jane Saunders. -

The Inventory of the Aaron Spelling Collection #1759

The Inventory of the Aaron Spelling Collection #1759 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Spelling, Aaron #1759 10/13/09 Preliminary Listing I. Manuscripts. Box 1 A. Teleplays. 1. “Sunset Beach.” a. Episode 0001, final taping draft, 69 p.,10/16/96. [F. 1] b. Episode 0002, final taping draft, 77 p., 10/16/96. c. Episode 0003, final taping draft, 76 p., 10/18/96. [F. 2] d. Episode 0004, final taping draft, 86 p., 10/21/96. e. Episode 0005, final taping draft, 94 p., 10/23/96. [F. 3] f. Episode 0006, revised, 85 p., 11/7/96. g. Episode 0007, 88 p., air date 1/14/97. [F. 4] h. Episode 0008, 84 p., air date 1/15/97. i. Episode 0009, 91 p., air date 1/16/96. [F. 5] j. Episode 0010, 88 p., air date 1/17/96. k. Episode 0011, 77 p., air date 1/20/96. [F. 6] l. Episode 0012, 88 p., air date 1/21/96. m. Episode 0013, 83 p., air date 1/22/97. [F. 7] n. Episode 0014, 81 p., air date 1/23/97. o. Episode 0015, 82 p., air date 1/24/97. [F. 8] p. Episode 0016, revised, 12/5/96. q. Episode 0017, 75 p.; tape date 12/17/96; air date 1/19/97. [F. 9] r. Episode 0018, 75 p.; tape date 12/18/96; air date 1/30/97. s. Episode 0019, 81 p.,; tape date 12/19/96; air date 1/31/97. [F. 10] t. Episode 0020, revised taping draft, 72 p., 12/16/96. -

Unforgiven. 070903

Ditte Friedman. Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. 070903. 1 Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. Ditte Friedman -- -- Draft for Lic.Theol. Seminar Draft 2007 September 21 Ditte Friedman. Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. 070903. 2 Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Background 1.2 Purpose and Problem 1.3 Material 1.4 Theory and Method 2. The Western 2.1 The Western as Idea 2.2 A New World Genre Begins 2.3 The Western as Genre 2.4 A Genre Finds a Voice 2.5 The New Western: the Development of Character 3 Background and Synopsis 4 Reading Unforgiven 4.1 The Critics 4.2 Deeper Readings and Thematic Analysis 4.2.1 Socio-Cultural Inquiry The American West as Nomos The Western as Nomos Law Justice 4.2.2 Historical Frame Evolving Democratic Polity Community Nation Building The American West as History An Inquiry into How We Understand History 4.2.3 Social Issues Gender Relations Property Rights Feminism Violence 4.2.4 Film-specific Commentary Western Movies Revisionism in Western Movies Genre Reconstruction, Transformation, and Revival The General Nature of Film Ditte Friedman. Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. 070903. 3 4.2.5 Nomothetic Issues Myth and Iconography Transcendence Motion The Land 5 Analysis: Reflections on Unforgiven 6 Conclusion 7 Films Cited 8 Television Shows Cited 9 References Ditte Friedman. Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. 070903. 4 2. The Western A voice of one calling: “In the desert prepare the way for the LORD; make straight in the wilderness a highway for our God. Every valley shall be raised up, every mountain and hill made low; the rough ground shall become level, the rugged places a plain.