FJ4.1 Mingant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Best Bets

Sunday SUNDAY PRIME TIME APRIL 8 S1 – DISH S2 - DIRECTV Best Bets 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 S1 S2 WSAZ WSAZ NBC News Dateline NBC Harry's Law "The Celebrity Apprentice "Ad Hawk" A celebrity WSAZ :35 Storm 3 3 NBC News Lying Game" (N) goes on a tirade against a teammate. (N) News Stories WLPX 5:30 < Space Cowboys ('00) Tommy Lee Jones, Clint < The Visitor ('07) Haaz Sleiman, Richard Jenkins. A < Rebound ('05) ION Eastwood. NASA recruits hotshot pilots to repair a satellite. professor finds a couple living in his NY apartment. Martin Lawrence. 29 - 5:00 < Out of Bounds World's Funniest Masters of Illusion < Freeway ('96) Reese Witherspoon. A Crook and Music TV10 - - ('03) Sophia Myles. Moments troubled young girl flees the foster-care system. Chase Row WCHS Eyewit- World America's Funniest Once Upon a Time GCB "Turn the Other GCB "Sex Is Divine" Eyewit- :35 Ent. ABC ness News News Home Videos "7:15 a.m." Cheek" (N) (N) ness News Tonight 8 8 WVAH Big Bang Two and a The Cleveland The B.Burger Family American Eyewitness News at Wrestling Ring of FOX Theory Half Men Simpsons Show Simpsons "Torpedo" Guy Dad 10 p.m. Honor 11 11 WOWK 2:00 Golf Masters 60 Minutes The Amazing Race (N) The Good Wife "The CSI: Miami "Habeas 13 News Cold Case CBS Tournament (L) Death Zone" Corpse" (SF) (N) Weekend 13 13 WKYT 2:00 Golf Masters 60 Minutes The Amazing Race (N) The Good Wife "The CSI: Miami "Habeas 27 :35 CBS Tournament (L) Death Zone" Corpse" (SF) (N) NewsFirst Courtesy - - WHCP < The Addams Family A greedy lawyer < Addams Family Values The family must Met Your Met Your The King The King CW tries to plunder the family's fortune. -

Nixon, in France,11

SEE STORY BELOW Becoming Clear FINAL Clearing this afternoon. Fair and cold tonight. Sunny., mild- Red Bulk, Freehold EIMTION er tomorrow. I Long Branch . <S« SeUdlf, Pass 3} Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 173 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 1969 26 PAGES 10 CENTS ge Law Amendments Are Urged TRENTON - A legislative lative commission investigat- inate the requirement that where for some of die ser- the Monmouth Shore Refuse lection and disposal costs in Leader J. Edward CrabieJ, D- committee investigating the ing the garbage industry. there be unanimous consent vices tiie authority offers if Disposal Committee' hasn't its member municipalities, Middlesex, said some of the garbage industry yester- Mr. Gagliano called for among the participating the town wants to and the au- done any appreciable work referring the inquiry to the suggested changes were left day heard a request for amendments to the 1968 Solid municipalttes in the selection thority doesn't object. on the problems of garbage Monmouth County Planning out of the law specifically amendments to a 1968 law Waste Management Authority of a disposal site. He said the The prohibition on any par- collection "because we feel Board. last year because it was the permitting 21 Monmouth Saw, which permits the 21 committee might never ticipating municipality con- the disposal problem is funda- The Monmouth Shore Ref- only way to get the bill ap- County municipalities to form Monmouth County municipal- achieve unanimity on a site. tracting outside the authority mental, and we will get the use Disposal Committee will proved by both houses of the a regional garbage authority. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

To December 31, 2021 the Los Angeles Acting Conservatory

*Catalog effective: March 1, 2020 (TBD by approval) to December 31, 2021 The Los Angeles Acting Conservatory (LAAC) is a private institution and is seeking approval for operation by the Bureau of Private Postsecondary Education (BPPE). Approval to operate means the institution is compliant with the minimum standards contained in the California Private Postsecondary Education Act of 2009 (as amended) and Division 7.5 of Title 5 of the California Code of Regulations. www.bppe.ca.gov This catalog is reviewed and updated each school year. As a prospective student, you are encouraged to review this catalog prior to signing an enrollment agreement. You are also encouraged to review the School Performance Fact Sheet, which must be provided to you prior to signing an enrollment agreement. You may request a copy of the catalog and SPFS by emailing [email protected] 1 Location & Contact Info 3 History 4 Purpose 4 Mission 4 Objectives 4 Educational Programs 5 Associate Degree in Acting 5 Associate Degree in Filmmaking 16 Admission Requirements 22 Financial Aid Policy 25 Return & Cancellation Policies 26 Notice Concerning Transferability of Units Earned at Our School 28 Attendance & Scheduling Policy 29 Student Services 31 Academic & Grading Policy 33 Licensing & Approvals 37 Facility & Equipment 39 Library Resources 40 Disciplinary Policy 43 Code of Conduct 47 International Student Information 53 Faculty 57 Academic Calendar 65 2 Location & Contact Info Nestled between a café, salon, retail shops, and a popular restaurant, Edgemar Center for the Arts is the anchor of the Edgemar complex on Main Street in Santa Monica. A couple blocks away from the beach, near the 10 freeway, the Los Angeles Acting Conservatory (LAAC) is housed in its own state-of-the-art building design by renowned architect Frank Gehry, which includes two theater spaces and an art gallery. -

Crisis Spurs Vast Change in Jobs Trump,Speaking in the White Faces a Reckoning

P2JW090000-4-A00100-17FFFF5178F ADVERTISEMENT Breaking news:your old 401k could be costing you. Getthe scoop on page R14. **** MONDAY,MARCH 30,2020~VOL. CCLXXV NO.74 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 Last week: DJIA 21636.78 À 2462.80 12.8% NASDAQ 7502.38 À 9.1% STOXX 600 310.90 À 6.1% 10-YR. TREASURY À 1 26/32 , yield 0.744% OIL $21.51 g $1.12 EURO $1.1139 YEN 107.94 In Central Park, a Field Hospital Is Built for Virus Patients Trump What’s News Extends Distance Business&Finance Rules to edical-supplies makers Mand distributors are raising redflagsabout what April 30 they sayisalack of govern- ment guidanceonwhereto send products, as hospitals As U.S. death toll passes competefor scarce gear amid 2,000, experts call for the coronavirus pandemic. A1 GES staying apart amid Washingtonisrelying on IMA the Fed, to an unprecedented need formoretesting degree in peacetime,topre- GETTY servebusinessbalancesheets SE/ President Trump said he was as Congressreloads the cen- extending the administration’s tral bank’sability to lend. A4 ANCE-PRES social-distancing guidelines Manyactivist investorsare FR through the end of April as the walking away from campaigns U.S. death toll from the new GENCE or settling with firms early as /A coronavirus surgedpast 2,000 some demands seem less over the weekend. pertinent in altered times. B1 ANCUR BET Thestock market’s unri- By Rebecca Ballhaus, valed swingsthis month have KENA Andrew Restuccia OPEN ARMS: The Samaritan’s Purse charity set up an emergency field hospital in Central Park on Sunday near Mount Sinai Hospital, ignited even more interest and Jennifer Calfas which it said would be used to care for coronavirus patients. -

Feminist Art, the Women's Movement, and History

Working Women’s Menu, Women in Their Workplaces Conference, Los Angeles, CA. Pictured l to r: Anne Mavor, Jerri Allyn, Chutney Gunderson, Arlene Raven; photo credit: The Waitresses 70 THE WAITRESSES UNPEELED In the Name of Love: Feminist Art, the Women’s Movement and History By Michelle Moravec This linking of past and future, through the mediation of an artist/historian striving for change in the name of love, is one sort of “radical limit” for history. 1 The above quote comes from an exchange between the documentary videomaker, film producer, and professor Alexandra Juhasz and the critic Antoinette Burton. This incredibly poignant article, itself a collaboration in the form of a conversation about the idea of women’s collaborative art, neatly joins the strands I want to braid together in this piece about The Waitresses. Juhasz and Burton’s conversation is at once a meditation of the function of political art, the role of history in documenting, sustaining and perhaps transforming those movements, and the influence gender has on these constructions. Both women are acutely aware of the limitations of a socially engaged history, particularly one that seeks to create change both in the writing of history, but also in society itself. In the case of Juhasz’s work on communities around AIDS, the limitation she references in the above quote is that the movement cannot forestall the inevitable death of many of its members. In this piece, I want to explore the “radical limit” that exists within the historiography of the women’s movement, although in its case it is a moribund narrative that threatens to trap the women’s movement, fixed forever like an insect under amber. -

Following Is a List of All 2019 Festival Jurors and Their Respective Categories

Following is a list of all 2019 Festival jurors and their respective categories: Feature Film Competition Categories The jurors for the 2019 U.S. Narrative Feature Competition section are: Jonathan Ames – Jonathan Ames is the author of nine books and the creator of two television shows, Bored to Death and Blunt Talk His novella, You Were Never Really Here, was recently adapted as a film, directed by Lynne Ramsay and starring Joaquin Phoenix. Cory Hardrict– Cory Hardrict has an impressive film career spanning over 10 years. He currently stars on the series The Oath for Crackle and will next be seen in the film The Outpostwith Scott Eastwood. He will star and produce the film. Dana Harris – Dana Harris is the editor-in-chief of IndieWire. Jenny Lumet – Jenny Lumet is the author of Rachel Getting Married for which she received the 2008 New York Film Critics Circle Award, 2008 Toronto Film Critics Association Award, and 2008 Washington D.C. Film Critics Association Award and NAACP Image Award. The jurors for the 2019 International Narrative Feature Competition section are: Angela Bassett – Actress (What’s Love Got to Do With It, Black Panther), director (Whitney,American Horror Story), executive producer (9-1-1 and Otherhood). Famke Janssen – Famke Janssen is an award-winning Dutch actress, director, screenwriter, and former fashion model, internationally known for her successful career in both feature films and on television. Baltasar Kormákur – Baltasar Kormákur is an Icelandic director and producer. His 2012 filmThe Deep was selected as the Icelandic entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 85th Academy Awards. -

EB Awarded Seawolf Contract Inside Today

16— MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday, May 3.1991 1. 88 TAG SALES aiCARSFORaJUJfl S2 TRUCKS ft VANS 94 MOTORCYCLES ft MOPBDS FORD-1978 Galaxy. (^11 FOR SALK after 1pm, 645-1218. DODGE-1982 Van. HONDA-1978 CX500 Very good condition. Cargo, 8 passenger, Road bfta. Shaft drive, f i t ! HUGE Asking $500. slant 6. Automatic, 59K water cooled, well 10 FAMILY SALE! IMPALA-1980. Power miles, good tires, reese maintained. 7500 miles. Furniture, antiques, books, Steering, power brakes hitch. m X ) . 643-1653. $850. Paul, 243-7855 toys, china, glass, beauti power windows, air or 646-3383.___________ ful clothes, giflware, box conditioning. Runs MOTORCYLE.-lnsurance. LAWN CARE PAINTING/ CARPENTRY/ HEATING/ lo tsA M O iS I PAPERING REMODELING PLUMBING good. Body in good SSCAMFERSft Friendly service, com Rain or Shine shape. High mileage. petitive raes, same day FrI., Sat. and Sun. TRAILERS H anrhpH tFr M pralb YARDMASTERS WEXaLFSPAtmNGCO. KITCHBIA BATH REMODELING hs&lBHon and Reolaoenient Asking $450 or best coverage. Crockett Spring Clean-Up VIsI our beaudM Showroom or call lor 9am-4pm offer. Cash or bank 1984-YELLOWSTONE Agency, 643-1577. QuaMy w oikata olOI,Gas&Beciric check. 649-4379. Lawns, Bushss, Trees Cut reasonable ptfce! your tree estimate. 68 Blgdow Street PARK MODEL. 38 X H ER ITA G E •Vyiater Heaters Yards, gutters, garages Interior & Exterior ■Warm Air Funaces Manchester PLYMOUTH-VOYAGER 12. Winter package. 25 KITCHEN a BATH CENTER S E 1987 59K, air, AM/ Foot Awning (9 X 26). Looking for an daaned. U w n FerWzing. App«- Free Estimates 254 Broad Street ■Bciers FM, luggage rifok. -

Arts, Culture and Media 2010 a Creative Change Report Acknowledgments

Immigration: Arts, Culture and Media 2010 A Creative Change Report Acknowledgments This report was made possible in part by a grant from Unbound Philanthropy. Additional funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Ford Foundation, Four Freedoms Fund, and the Open Society Foundations supports The Opportunity Agenda’s Immigrant Opportunity initiative. Starry Night Fund at Tides Foundation also provides general support for The Opportunity Agenda and our Creative Change initiative. Liz Manne directed the research, and the report was co-authored by Liz Manne and Ruthie Ackerman. Additional assistance was provided by Anike Tourse, Jason P. Drucker, Frances Pollitzer, and Adrian Hopkins. The report’s authors greatly benefited from conversations with Taryn Higashi, executive director of Unbound Philanthropy, and members of the Immigration, Arts, and Culture Working Group. Editing was done by Margo Harris with layout by Element Group, New York. This project was coordinated by Jason P. Drucker for The Opportunity Agenda. We are very grateful to the interviewees for their time and willingness to share their views and opinions. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works closely with social justice organizations, leaders, and movements to advocate for solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and promising solutions; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

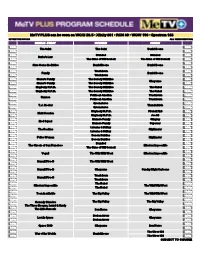

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

Move Over, Amateurs

Web Video: Move Over, Amateurs As more professionally produced content finds a home online, user- generated video becomes less alluring to viewers—and advertisers by Catherine Holahan November 20, 2007 Amateur filmmakers hoping to win fame for amusing moments captured on camcorder ought to stick to TV's long-running America's Funniest Home Videos. These days they're not getting much love on the Web. One after another, online video sites that have long showcased such fare as skateboarding dogs and beer-drenched parties are scaling back their focus on user- generated clips, often in favor of professionally produced programming. "People would rather watch content that has production value than watch their neighbors in the garage," says Matt Sanchez, co-founder and chief executive of VideoEgg, a company that provides Web video tools, ads, and advertising features for online video providers and Web application developers. On Nov. 13 social networking site Bebo said it would open its pages to top media companies in hopes of luring and engaging viewers. "As more and more interesting content from major media brands becomes available, [online viewers] are going to share that more and more because those are the brands they identify with," says Bebo President Joanna Shields. Another site, ManiaTV, recently canceled its user-generated channels altogether (BusinessWeek.com, 10/22/07). The 3,000 user-generated channels simply didn't pull in enough viewers, ManiaTV CEO Peter Hoskins says. Roughly 80% of people were watching the professional content produced by celebrities such as musician Dave Navarro and comedian Tom Green. "What we found out is, we don't need the classical user-generated talent when we have the Hollywood talent that wants to Coverage secured by Kel & Partners www.kelandpartners.com work with us," Hoskins says.