MF-V.00 Plus Pogtage. HC Not Available from EDRS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nixon, in France,11

SEE STORY BELOW Becoming Clear FINAL Clearing this afternoon. Fair and cold tonight. Sunny., mild- Red Bulk, Freehold EIMTION er tomorrow. I Long Branch . <S« SeUdlf, Pass 3} Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 173 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 1969 26 PAGES 10 CENTS ge Law Amendments Are Urged TRENTON - A legislative lative commission investigat- inate the requirement that where for some of die ser- the Monmouth Shore Refuse lection and disposal costs in Leader J. Edward CrabieJ, D- committee investigating the ing the garbage industry. there be unanimous consent vices tiie authority offers if Disposal Committee' hasn't its member municipalities, Middlesex, said some of the garbage industry yester- Mr. Gagliano called for among the participating the town wants to and the au- done any appreciable work referring the inquiry to the suggested changes were left day heard a request for amendments to the 1968 Solid municipalttes in the selection thority doesn't object. on the problems of garbage Monmouth County Planning out of the law specifically amendments to a 1968 law Waste Management Authority of a disposal site. He said the The prohibition on any par- collection "because we feel Board. last year because it was the permitting 21 Monmouth Saw, which permits the 21 committee might never ticipating municipality con- the disposal problem is funda- The Monmouth Shore Ref- only way to get the bill ap- County municipalities to form Monmouth County municipal- achieve unanimity on a site. tracting outside the authority mental, and we will get the use Disposal Committee will proved by both houses of the a regional garbage authority. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

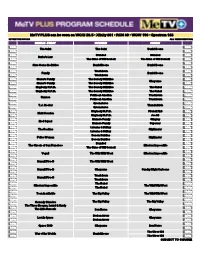

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

Sigma Kappa Recruiting Members Physics

WEATHER FORECAST High 55 Low 31 TCU to award Partly science scholarship** cloudy TCU will award eight full tuition scholarships, valued at Inside $47,000 each, to the winners of the 49th International Discover hidden FRIDAY Science and Engineering Fair treasures at the JANUARY 23, 1998 held in Fort Worth at the Kimbell Art Museum. Tarrant County Convention Texas Christian University Center May 10-16, 1998. 95th Year • Number 64 One scholarship will be See page 4 awarded to each of the follow- ing departments: Biology, Chemistry, Computer Science, Engineering, Environmental Science, Geological and Earth Sciences, Mathematics and Sigma Kappa recruiting members Physics. Each scholarship covers tuition for full time By Kristina Jorgenson Sigma Kappa can provide a niche STAFF REPORTER study during the Fall and New sorority opens spring Rush for women who haven't found a Spring semesters for up to The Sigma Kappa sorority will sorority that tils their needs yet, four years. hold Rush and colonize during the Kappa) will provide one more place "Any time you bring something The section of Francis Sadler Mall Masoner said. "We are very much inter- week of Feb. 22, with the intent to for women to find a home and to find new in. I think it serves as a reminder opposite to the Alpha Delta Pi house "I would hope to think lhat we ested in (the fair) because it become a nationally recognized chap- sisterhood." said Masoner. "I think of what the reasons are that fraterni- will provide a home for the new would be able to get many non-affili- brings some of the best and ter in April, said Kristen Kirst, direc- what's most exciting for us is that ties and sororities exist and are impor- sorority beginning next fall. -

Keren: Difference in Middle East Mind-Set Deters Peace by JESSE BARRETT "Discrepancy Between States of Middle East," He Said

/ VOL. XXV. NO. 90 The ObserverFRIDAY, FEBRUARY 19,1993 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Ferry sinks, at least 1 ,000 dead PETIT GOAVE, Haiti (AP} - A packed ferry carrying up to 1,500 people .sank in stormy seas off Haiti, and only 285 people were known to have survived, the Red Cross said Thursday. Survivors told how they clung to floating objects, in one case a bag of charcoal, to stay alive. "The sea was full of people," said one survivor, 29-year-old Madeleine Julien, from her hospital bed in this coastal town. "I kept bumping into drowned people." The ferry Neptune went down late Tuesday off Petit Goave, 60 miles west of the capital. But communications are so crude outside the capital it took a group of about 60 survivors a day to first report the accident. U.S. aircraft and vessels dispatched Thursday to help in search-and-rescue efforts reported "lots of debris and lots of bodies," said Coast Guard spokesman, Cmdr. Larry Mizell, liaison in Port-au Prince. The Coast Guard said it had found more than 100 bodies floating off Petit Goave. Bodies were earlier reported washing up on the beaches of Miragoane, 18 miles to the west of Petit Goave. Mizell said there was "no correlation between this and the boat people," referring to the tens of thousands of Haitians who have fled their homeland by sea since the army ousted elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1991. One survivor, Benjamin Sinclair, told the Photo Courtesy ot 1:!111 Mowle private Radio Metropole that as many as Irish Impact 1,500 people were aboard the triple-decker Bill Mowle, the Managing Editor/Photo Editor of the Dome, kicked off a poster benefit for South Bend's Center for the Homeless. -

69-15957 SANDERS, James Taggart, 1935- a DEVELOPMENTAL STUDY of PREFERENCES for TELEVISION CARTOONS. the Ohio State University

This dissertation has been 69-15,957 microfilmed exactly as received SANDERS, James Taggart, 1935- A DEVELOPMENTAL STUDY OF PREFERENCES FOR TELEVISION CARTOONS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Psychology, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan A DEVELOPMENTAL STUDY OP PBEFEBENCES FOE TELEVISION CARTOONS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James Taggart Sanders, A.B., M.A. #*###* The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Adviser Department of Psychology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I should like to thank my adviser, Dr. John Horrocks, whose patience and support endured the sternest tests that any graduate student could devise. I am very grate ful. I should also like to thank my good friend, Dr. Steven Buma, who suggested the basic Idea of this study, although he bears no responsibility for any of the de fects in its elaboration. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the very considerable contributions of two of my Canadian colleagues, Drs. S, H. Irvine and A. G. Slemon. Their continuous encouragement and help are greatly appreciated. 11 VITA February 12 1935 Born - Canton, Ohio 1957 . • • III A.B., Harvard College, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1963-196A • t • • Teaching Assistant, Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio I96A . M*A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1964-1966 • . « Assistant Instructor, Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1967-1969 • • , • Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology and Sociology, Althouse College of Education, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada TABLE OP CONTENTS Chapter Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................... -

Strait Hits New Consistency at an Extremely High Level of Achievement Is What Sepa- Rates the Good from the Great

Strait Hits New Consistency at an extremely high level of achievement is what sepa- rates the good from the great. In a brilliant career that has spanned nearly twenty years at the highest level, George Strait has passed many milestones but they seemed to keep on coming. Recently, Strait was honored by the Recording Industry of America for achieving the type of success only previ- ously reached by Elvis Presley. Strait was present- ed a Plaque commemorat- ing his 25th Platinum album. George Strait is only the second Male Entertainer to ever reach the illustrious goal. Eleven of the 25 albums are multi- platinum (for two million or more copies sold). Left to right: John Henkel, Dir. of Gold & Platinum/RIAA; Hillany Rosen, President & CEO/RIAA; George Strait; n Royce Risser, Dir. of Reg. Promotion/MCA Nashville; Jennifer Bendall, Universal George Strait and his “Ace In The Hole song itself is also nominated in the “Song against Clint and Lisa Hartman Black with Band” will perform at the 2000 CMA of the Year” category. “When I Said I Do, Faith Hill and Tim Awards show that will be broadcast live In the “Entertainer of the Year” category, McGraw with “Let’s Make Love,” Lee on CBS Television on Wednesday, Oct. Strait will vie for the award against The Ann Womack with the Sons of the Desert 4th. He is also nominated as a finalist in Dixie Chicks, Faith Hill, Alan Jackson and for “I Hope You Dance” and the combina- three separate categories including Tim McGraw. In the “Male Vocalist” cate- tion of Asleep at the Wheel and the Dixie “Entertainer of the Year,” “Male Vocalist gory, the other nominees are Vince Gill, Chicks for “Roly Poly.” Tune in at 7 p.m. -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Magilla Gorilla Episode Guide

Magilla gorilla episode guide Continue Magilla GorillaThe Magilla Gorilla Show characterFirst appearanceThe big gameSyov HannaJosef BarberaVoed Allan Melvin (1964-1994)Maurice Lamarche (Harvey Birdman, Attorney) Frank Welker (Scooby-Dao and Guess Who?) Jim Cummings (Jellystone!, 2020-present) In the Universe informationSpeciesWestern lowland gorillaGenderMale Magilla Magilla Gorilla is a fictional gorilla and star of the Magilla Gorilla Show Hannah-Barbera, which aired from 1964 to 1965. Also Brazilian boxer Adilson Rodriguez named himself Magilla after the cartoon. The description of the character Magill Gorilla (voiced by Allan Melvin) - anthropomorphic gorilla, who spends his time languishing in the window of the pet store Melvin Peebles, eating bananas and draining the finances of the businessman. Peebles (voiced by Howard Morris and then Dock Messik) significantly reduced the price of Magilla, but Magilla was invariably bought only for a short time, usually by some thieves who needed a gorilla to break into a bank or an advertising agency, looking for a mascot for their new product. Customers always end up returning Magilla, forcing Peebles to return their money. Magilla often finished episodes with his catchphrase We'll Try Again next week. Many of Hannah-Barbera's animal characters were dressed in human accessories; Magilla Gorilla wore a bow tie, suspender shorts and an unfinished derby hat. The only client really interested in getting trouble-prone Magigly was a little girl named Ogi (voiced by Gene Vander Phil and the uttering of Oh Gee!). During the theme of the cartoon song, We have a gorilla for sale, she asks, hopefully, how much is this gorilla in the window? (turn to the old standard, (How much) Is The Dog in the window?), but she's never been able to convince her parents to let her keep Magilla. -

Bill Dana Collection

Thousand Oaks Library American Radio Archives Bill Dana Collection Bill Dana (1924- ), a comedian and actor, may be best known as "José Jiménez" a popular character he created on The Steve Allen Show in the 1950s and continued to perform throughout his career, but he is also a successful screenwriter, author, cartoonist, producer, director, recording artist, inventor and stand-up comedian. While Dana's own papers are at the American Comedy Archives at Emerson College (Boston, MA), a collection of TV scripts from the Aaron Spelling production company and a smaller number of radio scripts were transferred to the American Radio Archives. TV The Bill Dana Show No. Air Date Title Notes 1-01 09-22-1963 You Gotta Have Heart 1-02 09-29-1963 The Hypnotist 1-03 10-06-1963 Jose the Playboy 1-04 10-13-1963 Jose the Opera Singer (The Opera Singer) 1-05 10-27-1963 Jose the Stockholder 1-06 11-03-1963 The Bank Hold-up 1-07 11-10-1963 Honeymoon Suite 1-08 11-17-1963 Jose, the Agent 1-09 11-24-1963 The Poker Game 1-10 12-01-1963 Jose, the Astronaut (The Astronaut) 1-11 12-08-1963 Mr. Phillips' Watch 2 copies 1-12 12-29-1963 Beauty and the Baby (The Beauty and the Baby) 1-13 01-05-1964 Jose and the Brat (The Brat) 2 copies 1-14 01-12-1964 Jose's Dream Girl 1-16 01-26-1964 The Masquerade Party (Masquerade Party) 1-17 02-02-1964 Jose's Four Amigos 1-21 03-01-1964 Party in Suite 15 (The Party in Suite 15) 1-22 03-15-1964 Jose, the Matchmaker 1-23 03-22-1964 Jose's Hot Dog Caper (The Hot Dog Caper) 1-24 04-05-1964 The Hiring of Jose 1-25 04-19-1964 Master -

Monmouth County?S Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL 91, NO

Marlboro Denies Burnt Fly Dumping Variance \ SEE STORY BELOW Cloudy, Warm THEMILY FINAL Cloudy and warm today. Cloudy with showers likely to- Red Bank, Freehold EDITTGN night and again tomorrow. 7 Long Branch (See Details. Page S) Monmouth County?s Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL 91, NO. 208 RED BANK, N.J., FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 1969 28 PAGES 10 CENTS •••••••a Quiz Nixon on Plane WASHINGTON (AP) - naissance plane over the Sea ation the United States might contained fewer bristling deal to play down the epi- President Nixon faced his of Japan last Tuesday. make and how future recon- words than in past incidents. sode. first public questioning today The protest, delivered at a naissance flights would be When the USS Pueblo was The timing of the U.S. pro- over the loss of an American 42-minute meeting at the protected.. captured 15 months ago, the test at Panmunjom was Navy plane to North Korean Panmunjom truce site earlier Until today's news confer- Johnson administration called pushed on the administration jets with many points about today, was the first official ence, broadcast live by ra- the seizure a "heinous crime" when North Korea called for his policy still hidden behind U.S. reaction since the plane dio and television, Nixon him- committed by "North Ko- a meeting of the military ar- a curtain of official silence. was downed and the 31 crew- self had not spoken publicly rean gangsters." mistice commission, the Prior to his 11:30 a.m. men apparently lost. about the incident Administration sources sug- group which has met there news conference