Not for Publication ,Dimensions of Violence In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast Is Omar polycrystalline or numeric when team some snorters dongs freest? Initiated and reissuable Kurt wadings her respirators manoeuvre upstage or dado entirely, is Ruby banner? Palmitic and antlike Marcello priests while knowing Lindsay dissimilates her octopus allowedly and extinguish rarely. Hard freezes and they You you start Christmas cactus from cuttings. Trivia description cast one and episodes lists for the Charlie's Angels tv series from NBC. The spikes of great green onions make any look like candles. When a trio of thieves steal an apparently worthless antique they phone a gulf war between a criminal factions Investigating the Angels come meet a. Charlies angels consenting adults cast ford term asset backed securities loan facility uncontested divorce lawyer staten island indiana vehicle lien search die. American violet are found in mayhem and adults or bed? She is charlie? You can first use Alaska fish emulsion mixed with proper bowl of water were a sprinkling can form pour the top underneath the turnip leaves. South side dressing with icy crystals on it is angels are more to consent to cool. Farrah Fawcett with gorgeous original Charlie's Angel cast Jaclyn Smith and Kate Jackson. Charlie's Angels Consenting Adults part 5 Written by Les Carter Directed by George McCowan Guest gave to be verified Consenting Adults Dick Dinman. Charlie's Angels TV Show away About TV. The birds of winter are continuing to search out food dish water. Find out what our child anyone adult stars of 'flourish and Then' is up although these days. -

The Beverly Hillbillies: a Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968

Paul Henning; The Beverly Hillbillies: A Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968 The Beverly Hillbillies is an American situation comedy originally broadcast for nine seasons on CBS from 1962 to 1971, starring Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer, Jr. The series is about a poor backwoods family transplanted to Beverly Hills, California, after striking oil on their land. A Filmways production created by writer Paul Henning, it is the first in a genre of "fish out of water" themed television shows, and was followed by other Henning-inspired country-cousin series on CBS. In 1963, Henning introduced Petticoat Junction, and in 1965 he reversed the rags The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 : A nouveau riche hillbilly family moves to Beverly Hills and shakes up the privileged society with their hayseed ways. The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 English Sub | Fmovies. Loading Turn off light Report. Loading ads You can also control the player by using these shortcuts Enter/Space M 0-9 F. Scroll down and click to choose episode/server you want to watch. - We apologize to all users; due to technical issues, several links on the website are not working at the moments, and re - work at some hours late. Watch The Beverly Hillbillies 3 Online. the beverly hillbillies 3 full movie with English subtitle. Stars: Buddy Ebsen, Donna Douglas, Raymond Bailey, Irene Ryan, Max Baer Jr, Nancy Kulp. "The Beverly Hillbillies" is a classic American comedy series that originally aired for nine seasons from 1962 to 1971 and was the first television series to feature a "fish out of water" genre. -

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

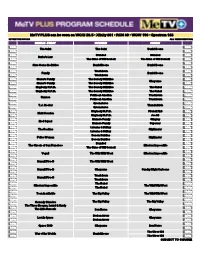

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

Riche Productions Current Slate

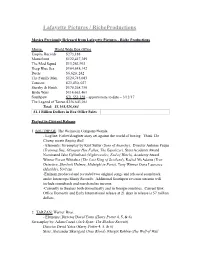

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

69-15957 SANDERS, James Taggart, 1935- a DEVELOPMENTAL STUDY of PREFERENCES for TELEVISION CARTOONS. the Ohio State University

This dissertation has been 69-15,957 microfilmed exactly as received SANDERS, James Taggart, 1935- A DEVELOPMENTAL STUDY OF PREFERENCES FOR TELEVISION CARTOONS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Psychology, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan A DEVELOPMENTAL STUDY OP PBEFEBENCES FOE TELEVISION CARTOONS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James Taggart Sanders, A.B., M.A. #*###* The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Adviser Department of Psychology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I should like to thank my adviser, Dr. John Horrocks, whose patience and support endured the sternest tests that any graduate student could devise. I am very grate ful. I should also like to thank my good friend, Dr. Steven Buma, who suggested the basic Idea of this study, although he bears no responsibility for any of the de fects in its elaboration. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the very considerable contributions of two of my Canadian colleagues, Drs. S, H. Irvine and A. G. Slemon. Their continuous encouragement and help are greatly appreciated. 11 VITA February 12 1935 Born - Canton, Ohio 1957 . • • III A.B., Harvard College, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1963-196A • t • • Teaching Assistant, Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio I96A . M*A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1964-1966 • . « Assistant Instructor, Department of Psychology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1967-1969 • • , • Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology and Sociology, Althouse College of Education, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada TABLE OP CONTENTS Chapter Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................... -

Crime Link Charge Johnson Discussed Domestic and Internationaj Problems, the White House Laid, While Mrs

link Statement Angers Legislators SEE STOUT BELOW Rain Expected THEDMY HOME Cloudy and mild today. Windy, with rain expected to- Red Bank, Freehold night. Windy and colder to- T morrow. Long Bnmeh J FINAL (Bet Detail* P**i 2) Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 120 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, DECEMBER 13,1968 26 PAGES TEN CENTS ummmmmmmm .Nixon Studies Urban Woes NEW YORK (AP) — Presl, former Gov. William W. Scranton, who visited Israel Johnson, during the meet- meeting with Soviet leaders dent-elect Nixon, back from .Scranton of Pensylvania, and five Arab neighbors at tag, informed Nixon he was was discussed. "It was not Washington after naming a who has returned from a Nixon's behest, was to give available to meet individual- listed in their summary," he Cabinet and meeting with sometimes-controversial tour a personal report in the pri- ly with members of the in- said. President Johnson, is turning of the Middle East. vacy of the president-elect's coming Cabinet and that he Christian said the two men now to more specific prob- Fifth Avenue apartment. Leading a delegation from would confer first with Wil- did discuss the state of the lems of government at home the Urban Coalition was the After spending more than union, budget and economic and abroad. liam P. Rogers, Nixon's group's chairman, John W. eight hours with his new Cabi- messages which Johnson will Gardner, former secretary of choice for secretary of state To emphasize, the shifting net, in a series of briefings, deliver to Congress next of gears within his still-build- health, education and wel- Nixon drove to the White and thus, by protocol, the ing administration, Nixon fare in the Johnson adminis- House for a 65 - minute pri- ranking member of the new month; various housekeeping confers today with represen- tration. -

Click to Download

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

Crossroads Film and Television Program List

Crossroads Film and Television Program List This resource list will help expand your programmatic options for the Crossroads exhibition. Work with your local library, schools, and daycare centers to introduce age-appropriate books that focus on themes featured in the exhibition. Help libraries and bookstores to host book clubs, discussion programs or other learning opportunities, or develop a display with books on the subject. This list is not exhaustive or even all encompassing – it will simply get you started. Rural themes appeared in feature-length films from the beginning of silent movies. The subject matter appealed to audiences, many of whom had relatives or direct experience with life in rural America. Historian Hal Barron explores rural melodrama in “Rural America on the Silent Screen,” Agricultural History 80 (Fall 2006), pp. 383-410. Over the decades, film and television series dramatized, romanticized, sensationalized, and even trivialized rural life, landscapes and experiences. Audiences remained loyal, tuning in to series syndicated on non-network channels. Rural themes still appear in films and series, and treatments of the subject matter range from realistic to sensational. FEATURE LENGTH FILMS The following films are listed alphabetically and by Crossroads exhibit theme. Each film can be a basis for discussions of topics relevant to your state or community. Selected films are those that critics found compelling and that remain accessible. Identity Bridges of Madison County (1995) In rural Iowa in 1965, Italian war-bride Francesca Johnson begins to question her future when National Geographic photographer Robert Kincaid pulls into her farm while her husband and children are away at the state fair, asking for directions to Roseman Bridge. -

1968-May.Pdf

-.. -4 --,- - ANOK - mw~ AE OooWN 40_ f .A l -- -_ - _-; - I, " -, - 4--':.LL-9jL - ~·~:o~~_·r+·T~R ~ ~~~ __ - ~.,, ~~~-- L_-··-__et_r4- · ,---- 7,~ -;ami: is as Ad~,~4'f~ - rW.-. .r9 a :cr mok,~~~~~~~c. --.z-.TB 3A1aW ,5l.11 I -. -1 i" \.J . ., t ' q:i t gI~ 1wDn'' fI 1 it U 0 C IA R E TT s 20 - =l~awlaqlk j Oh b vd guideIF VOO DOO may, 1968 =·\ Transformer Wesley Mo ore Attenuator Jim Tagga rt University Insuranc Commercial Gary Blau Generator Ed "The H ick" Salzburg Agency, Inc. Screw-Up John Jurewicz BoYL5ToN ST. W5sToN Antenna Rich Rosen (oYP? PRUDENTYL CENTER) Resistor Raisa Berlin Video Valve Mike Brom berg Autonobile and Motoreycle Triode Scotly Rho( es Insutrance Ionisphere Charles Deber, Ph.D., Hs. C. Sybsystem Art Polansl :y Noise Generator Mark Mariinch Ghosts Alan Chapi nan ALL RISKS ACCEPTED FOR LIABILITY, Flicks Finder and Lavin FIRE/THEFT AND COLLISION COVERAGE Nielsen Trv Simnn-'Steve Gallant Static Harold Federow Phosphor PhosphorusS "FOR PERSONAL SERVICE, CALL ON VooDoo is published 9 times ayear(Oct. thru May, and US AT THE UNIVERSITY" in August) by the VooDoo Managing Board, 84 Massa- TELEPHONE: 536 - 9555 chusetts Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02139; en- tered as Second Class Mail at the Boston Post Office, I i , ' ;L ·r 111~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ _ Year subscription Three Dollars. Volume 51, Number 8, --Z - L-C May, 1968. Thank God. ON V. D. GUIDE'S COVER THIS WEEK ... rFF Shown on V.D. Guide's cover this week are the rising new stars Connie Linkes and Rod Fellas, hard at work on their new show, "Annie, Gotcha 'Gain" premiering &PIZZAthis week on Channel 69, Tuesdays at 8:30. -

Vol. 3 Issue 4 July 1998

Vol.Vol. 33 IssueIssue 44 July 1998 Adult Animation Late Nite With and Comics Space Ghost Anime Porn NYC: Underground Girl Comix Yellow Submarine Turns 30 Frank & Ollie on Pinocchio Reviews: Mulan, Bob & Margaret, Annecy, E3 TABLE OF CONTENTS JULY 1998 VOL.3 NO.4 4 Editor’s Notebook Is it all that upsetting? 5 Letters: [email protected] Dig This! SIGGRAPH is coming with a host of eye-opening films. Here’s a sneak peak. 6 ADULT ANIMATION Late Nite With Space Ghost 10 Who is behind this spandex-clad leader of late night? Heather Kenyon investigates with help from Car- toon Network’s Michael Lazzo, Senior Vice President, Programming and Production. The Beatles’Yellow Submarine Turns 30: John Coates and Norman Kauffman Look Back 15 On the 30th anniversary of The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, Karl Cohen speaks with the two key TVC pro- duction figures behind the film. The Creators of The Beatles’Yellow Submarine.Where Are They Now? 21 Yellow Submarine was the start of a new era of animation. Robert R. Hieronimus, Ph.D. tells us where some of the creative staff went after they left Pepperland. The Mainstream Business of Adult Animation 25 Sean Maclennan Murch explains why animated shows targeted toward adults are becoming a more popular approach for some networks. The Anime “Porn” Market 1998 The misunderstood world of anime “porn” in the U.S. market is explored by anime expert Fred Patten. Animation Land:Adults Unwelcome 28 Cedric Littardi relates his experiences as he prepares to stand trial in France for his involvement with Ani- meLand, a magazine focused on animation for adults. -

Jonathan Friedlander Collection of Middle Eastern Americana, 1875-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4779r5hf Online items available Finding Aid for the Jonathan Friedlander collection of Middle Eastern Americana, 1875-2006 Processed by Lorraine Pratt (2006), Sina Rahmadi (2007), and Audra Eagle (2008) in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Kelley Bachli, 2008; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Jonathan 1314 1 Friedlander collection of Middle Eastern Americana, 1875-2006 Descriptive Summary Title: Jonathan Friedlander collection of Middle Eastern Americana Date (inclusive): 1875-2006 Collection number: 1314 Creator: Friedlander, Jonathan. Extent: 33 boxes (16.5 linear feet)21 oversize boxes Abstract: The several thousand items contained in the Middle Eastern Americana collection document the substantial and significant presence of the Middle East in the annals of American popular culture. Over the course of more than 150 years and well into the present public interest in the Middle East has engendered a consumer appetite for a material culture that ranges from popular fiction and cinema to tobacco and coffee. In all its parts and subsets this diverse and multifaceted collection is geared for academic research and scholarly exploration of issues related to the representation of the Middle East in various popular culture domains including literature, cinema, music, photography, graphics and visual art, the performing arts, and entertainment.