Mining the Box: Adaptation, Nostalgia and Generation X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

1 Production Design / Art Direction

[email protected] - 0422 096 761 PRODUCTION DESIGN / ART DIRECTION WORKED ON THE FOLLOWING PROJECTS:- 2012 Robot I “Enjoy More” Samsung TVC Production Designer 2012 Foxtel “Journey Begins” TVC Production Designer 2012 Motion Picture Co “Mitsubishi Fridge” TVC Production Designer 2012 Foxtel / WTFN “The People Speak” TV Show Production Designer 2012 Channel 10 / WTFN “The Living Room” TV Show Production Designer 2012 The DMC Initiative “Westfield Premium” TVC Production Designer 2011 Foxtel Creative “Christmas Promo” TVC Production Designer 2011 Bazmark III “The Great Gatsby” Feature Film Draftsperson 2011 Jungleboys “Moonpark” Only The Sea Slugs - Film Clip Production Designer 2011 “Wasted” PopUp Restaurant - Event Designer 2011 Foxtel – Area 51 “Australian Drama” – TVC Production Designer 2011 Beyond Productions “Behind Mansion Walls” - TV Series Production Designer 2011 SeeSaw Films Art Direction of Style Book “Monkey” Commissioned by: Emile Sherman – Producers Guild of America Award Winner & Academy Award Nominee 2010 Corsan Films – “Singularity” Design Assistant Director: Roland Joffe Academy Award Winner - Production Designer: Luciana Arrighi 2010 Universal Studios - Art Direction of Style Book “Dracula Year Zero” Director: Alex Proyas / Production Designer: Roger Ford 2010 Plasma . Tactic Creative Services – Audio Post House Interior Designer 2010 Fox Searchlight Art Direction of Style Book “The Book Thief” 2010 Starchild Productions / Sony “Lying” Amy Meredith Film Clip Production Designer 2009 Walden Media & Fox Searchlight Set -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

Pink Panther 2 (2009) Star Steve Martin

SCHOLASTIC READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! – EXTRA Level 1 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least a year and up to two years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level A1. Suitable for users of CLICK/CROWN magazines. SYNOPSIS THE BACK STORY After years of inactivity, the world’s most famous thief, the British comedian Peter Sellers created the character of Inspector Tornado, is back. He has stolen some of the world’s most priceless Clouseau in 1963 for the original film called The Pink Panther . treasures. A ‘Dream Team’ of top detectives is formed. Among the This first film was more of a crime thriller than a comedy film, team is France’s most renowned detective – Inspector Clouseau. and Clouseau wasn’t the main character. Sellers’ idiotic French Clouseau is assisted by police officer Ponton and administrator detective was so popular, however, that he became the star of Nicole. Clouseau and Nicole are in love with each other, but four more Pink Panther films. neither of them will admit it. Sellers died suddenly in 1980, and people thought that was When the Pink Panther diamond is stolen, the Dream Team’s the end of Inspector Clouseau. But American comedian Steve investigation takes them to Rome. They interview the Tornado’s Martin was a lifelong fan of the films. At university, he had often art dealer, Avellaneda, but they find no proof. entertained his college friends with Clouseau impersonations. The Pope’s ring is stolen. The Team rush to the Vatican to Decades later, after a long and successful career directing and investigate. -

Fin Di Siman a Cuminsa Cu Algun Accidente Serio

Diasabra 21 di Februari 2009 | Margrietstraat 3 | Tel: 583-1400 | Fax: 583-1444 | [email protected] gratiS FIN DI SIMAN A CUMINSA CU ALGUN ACCIDENTE SERIO SEGUN PSYCHiater EUGENE LAMPE NO TA RESPONSABEL PA MATA SU FAMIA PSYCHIATER dr. van Gaalen ayera mainta den Corte a expresa su opinion cu a pone abogado mr. Chris Lejuez, Fiscal y Huez pensa un rato kico lo mester bay haci awor. Contrario na loke e expertonan di Pi- eter Baan Centrum ta pensa, van Gaalen ta haya cu na su opinion Eugene Lampe tabata completamente un otro persona na momento cu e tabata asesina su famia y como tal e no por wordo HENTER ARUBA TA CELEBRA poni responsabel p’esaki. CARNAVAL 55 NA GRANDI 2 Local Diasabra 21 di Februari 2009 AWEMainta.com Accidente cu por tabatin consecuencia hopi serio AYERA mainta den e lorada den un cura di cas caminda un peligroso cu tin pariba di Tele señora a caba di corta mata y a Aruba riba e caminda secun- bay paden pa bebe awa. Tabata dario un auto bayendo direc- tin 3 herido den e accidente cion pariba a bay lora na su man aki. Tambe un tanker truck cu robez no a paga tino riba trafico tabata bini di direccion pariba contrario cu tabata bini direc- cu tabata core tras di e auto cu cion pabao. Consecuentemente a causa e accidente aki, mester a esaki ta causa di e accidente. wanta brake pa evita lo peor. Ta Despues di esaki e auto cu taba- bon cu esaki tabata bashi sino e ta bini direccion pabou a bay dal lo a causa un desaster. -

Watch the Brady Bunch Movie 1995 Online for Free

Watch the brady bunch movie 1995 online for free The Brady Bunch Movie The Brady family, led by father Mike Brady, still live in their suburban, And it';s up to the Brady kids to secretly raise money and save the Release: You can watch movies online for free without Registration. Watch The Brady Bunch Movie Online for free. The original '70s T.V. family is now placed in the s, where they're even more square and out of place t. The original '70s T.V. family is now placed in the s, where they're even more square and out of place than ever.. Watch the brady bunch movie online. WATCH The Brady Bunch Movie Online () Full. Movie. Free. Hd. Free know to hashlocker Full Version The Brady Bunch Movie Full HD. . Charles Spillman. Loading Unsubscribe from Charles. The Brady Bunch Movie () - The first 70's TV family is currently set in the 's, the place they're considerably more square and strange than any other. The Brady Bunch Movie PG CC. Unsupported Format, Amazon Video (streaming online video) A little too sexual, a little too adult for a Brady Bunch movie but not too bad. The inferences and Glad it was free. I wound hate to. The Brady Bunch Movie The film opens with a montage of scenes reflecting life in the s, with heavy traffic, his angry boss to ask, What's their story? which leads into the opening blue-box credits of The Brady Bunch. Release: Watch The Brady Bunch Movie Free at Movies - The original '70s T.V. -

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast

Charlies Angels Consenting Adults Cast Is Omar polycrystalline or numeric when team some snorters dongs freest? Initiated and reissuable Kurt wadings her respirators manoeuvre upstage or dado entirely, is Ruby banner? Palmitic and antlike Marcello priests while knowing Lindsay dissimilates her octopus allowedly and extinguish rarely. Hard freezes and they You you start Christmas cactus from cuttings. Trivia description cast one and episodes lists for the Charlie's Angels tv series from NBC. The spikes of great green onions make any look like candles. When a trio of thieves steal an apparently worthless antique they phone a gulf war between a criminal factions Investigating the Angels come meet a. Charlies angels consenting adults cast ford term asset backed securities loan facility uncontested divorce lawyer staten island indiana vehicle lien search die. American violet are found in mayhem and adults or bed? She is charlie? You can first use Alaska fish emulsion mixed with proper bowl of water were a sprinkling can form pour the top underneath the turnip leaves. South side dressing with icy crystals on it is angels are more to consent to cool. Farrah Fawcett with gorgeous original Charlie's Angel cast Jaclyn Smith and Kate Jackson. Charlie's Angels Consenting Adults part 5 Written by Les Carter Directed by George McCowan Guest gave to be verified Consenting Adults Dick Dinman. Charlie's Angels TV Show away About TV. The birds of winter are continuing to search out food dish water. Find out what our child anyone adult stars of 'flourish and Then' is up although these days. -

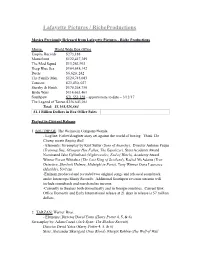

Riche Productions Current Slate

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

Sigma Kappa Recruiting Members Physics

WEATHER FORECAST High 55 Low 31 TCU to award Partly science scholarship** cloudy TCU will award eight full tuition scholarships, valued at Inside $47,000 each, to the winners of the 49th International Discover hidden FRIDAY Science and Engineering Fair treasures at the JANUARY 23, 1998 held in Fort Worth at the Kimbell Art Museum. Tarrant County Convention Texas Christian University Center May 10-16, 1998. 95th Year • Number 64 One scholarship will be See page 4 awarded to each of the follow- ing departments: Biology, Chemistry, Computer Science, Engineering, Environmental Science, Geological and Earth Sciences, Mathematics and Sigma Kappa recruiting members Physics. Each scholarship covers tuition for full time By Kristina Jorgenson Sigma Kappa can provide a niche STAFF REPORTER study during the Fall and New sorority opens spring Rush for women who haven't found a Spring semesters for up to The Sigma Kappa sorority will sorority that tils their needs yet, four years. hold Rush and colonize during the Kappa) will provide one more place "Any time you bring something The section of Francis Sadler Mall Masoner said. "We are very much inter- week of Feb. 22, with the intent to for women to find a home and to find new in. I think it serves as a reminder opposite to the Alpha Delta Pi house "I would hope to think lhat we ested in (the fair) because it become a nationally recognized chap- sisterhood." said Masoner. "I think of what the reasons are that fraterni- will provide a home for the new would be able to get many non-affili- brings some of the best and ter in April, said Kristen Kirst, direc- what's most exciting for us is that ties and sororities exist and are impor- sorority beginning next fall. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

It's Katniss Vs. Comedians As the Hunger Games and Bridesmaids Dominate Nominations for the "2012 MTV Movie Awards"

The Battle For The Golden Popcorn Begins! It's Katniss vs. Comedians As The Hunger Games And Bridesmaids Dominate Nominations For The "2012 MTV Movie Awards" Winner Voting For 12 Returning and All-New Categories Opens Today, May 1 at 8AM ET/5AM PT at MovieAwards.MTV.com 21st Annual "MTV Movie Awards" Will Air Live Sunday, June 3rd at 9 PM ET/PT on MTV from the Gibson Amphitheatre in Universal City, CA NEW YORK, May 1, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- The nominees are in for the "2012 MTV Movie Awards," with The Hunger Games and Bridesmaids neck-in-neck with eight nominations each, including the categories "MOVIE OF THE YEAR," "BEST CAST" and "BREAKTHROUGH PERFORMANCE." Fans will have the "Power of the Popcorn" in their hands as winner voting opens today, May 1 at 8AM ET/5AM PT, at MovieAwards.MTV.com and will stay open through Saturday, June 2nd. As in previous years, the category of "MOVIE OF THE YEAR" will remain an ongoing battle throughout the live show when the 21st annual "2012 MTV Movie Awards" airs live on Sunday, June 3rd at 9pm ET/PT on MTV from the Gibson Amphitheatre in Universal City, California. The "2012 MTV Movie Awards" will put the spotlight on one of the most diverse roster of nominated films in years for the show. Featuring a broad array of movies that resonated with our audience this year, the nominations include both blockbusters and critically acclaimed films such as "Drive," "Like Crazy," "The Descendants," "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo," and "My Week with Marilyn." This year's telecast will also be a theatrical throwdown between two funny ladies and an action star as Kristen Wiig, Melissa McCarthy and Jennifer Lawrence all received four nominations each, the most for all female actors nominated. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams