Television and Social Behavior; Reports and Papers, Volume I: Media Content and Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nixon, in France,11

SEE STORY BELOW Becoming Clear FINAL Clearing this afternoon. Fair and cold tonight. Sunny., mild- Red Bulk, Freehold EIMTION er tomorrow. I Long Branch . <S« SeUdlf, Pass 3} Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 173 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 1969 26 PAGES 10 CENTS ge Law Amendments Are Urged TRENTON - A legislative lative commission investigat- inate the requirement that where for some of die ser- the Monmouth Shore Refuse lection and disposal costs in Leader J. Edward CrabieJ, D- committee investigating the ing the garbage industry. there be unanimous consent vices tiie authority offers if Disposal Committee' hasn't its member municipalities, Middlesex, said some of the garbage industry yester- Mr. Gagliano called for among the participating the town wants to and the au- done any appreciable work referring the inquiry to the suggested changes were left day heard a request for amendments to the 1968 Solid municipalttes in the selection thority doesn't object. on the problems of garbage Monmouth County Planning out of the law specifically amendments to a 1968 law Waste Management Authority of a disposal site. He said the The prohibition on any par- collection "because we feel Board. last year because it was the permitting 21 Monmouth Saw, which permits the 21 committee might never ticipating municipality con- the disposal problem is funda- The Monmouth Shore Ref- only way to get the bill ap- County municipalities to form Monmouth County municipal- achieve unanimity on a site. tracting outside the authority mental, and we will get the use Disposal Committee will proved by both houses of the a regional garbage authority. -

The Philippines: Dismantling Rebel Groups

The Philippines: Dismantling Rebel Groups Asia Report N°248 | 19 June 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Rethinking Assistance to Former Rebels ......................................................................... 4 A. The Cautionary Tale of the MNLF ............................................................................. 4 B. The Dubious Legacy of Buybacks .............................................................................. 5 III. The Cordillera: Trial and Error ........................................................................................ 8 A. The History of the Conflict ........................................................................................ 8 B. The July 2011 Closure Agreement ............................................................................. 11 1. The many faces of the CPLA ................................................................................. 11 2. Terms ................................................................................................................... -

Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6h4nc876 No online items Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090 Processed by Timothy Holland and Joshua Amberg in the Center For Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Laurel McPhee, Fall 2005; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala, Caroline Cubé, Laurel McPhee and Amy Shung-Gee Wong. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 December 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase LSC.1090 1 Papers LSC.1090 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Stanley Chase papers Creator: Chase, Stanley Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1090 Physical Description: 157.2 Linear Feet(105 boxes, 12 oversize boxes, 27 map folders) Date (inclusive): circa 1925-2001 Date (bulk): 1955-1989 Abstract: Stanley Chase (1928-) was a theater, film, and television producer. The collection consists of production and business files, original production drawings, posters, press clippings, sound recordings, and scripts from his major projects. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisual materials. -

Guide to Women's History Resources at the American Heritage Center

GUIDE TO WOMEN'S HISTORY RESOURCES AT THE AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER "'You know out in Wyoming we have had woman suffrage for fifty years and there is no such thing as an anti-suffrage man in our state -- much less a woman.'" Grace Raymond Hebard, quoted in the New York Tribune, May 2, 1920. Compiled By Jennifer King, Mark L. Shelstad, Carol Bowers, and D. C. Thompson 2006 Edited By Robyn Goforth (2009), Tyler Eastman (2012) PREFACE The American Heritage Center holdings include a wealth of material on women's issues as well as numerous collections from women who gained prominence in national and regional affairs. The AHC, part of the University of Wyoming (the only university in the "Equality State") continues a long tradition of collecting significant materials in these areas. The first great collector of materials at the University, Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard, was herself an important figure in the national suffrage movement, as materials in her collection indicate. Hebard's successors continued such accessions, even at times when many other repositories were focusing their attentions on "the great men." For instance, they collected diaries of Oregon Trail travelers and accounts of life when Wyoming was even more of a frontier than it is today. Another woman, Lola Homsher, was the first formally designated University archivist and her efforts to gain materials from and about women accelerated during the service of Dean Krakel, Dr. Gene Gressley, and present director Dr. Michael Devine. As a result of this work, the AHC collections now contain the papers of pioneering women in the fields of journalism, film, environmental activism, literature, and politics, among other endeavors. -

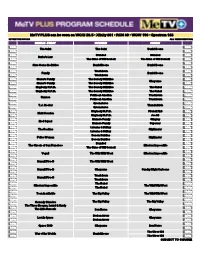

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

<Urutrnl Slaiur · .S Llrr Kly N Rm.S .Tlagaziur

<Urutrnl Slaiur ·.s llrr kly Nrm.s .tlagaziur Vol. 6, No . 34 Thursday, August 24, 1967 Ten Cents Cathy Dean, Dover; Susan Chaloux, Dover; Andy raQc~ '· Youngsters had a good time last weekend at the Jet' Festival. Milo; Lynn McDonald , Brownville Jet.; Rhonda Larabee, Dov- er; .Jane Jardine, Brownville J:ct. and their leader Mrs. Be hoto Sherry Harmon ancl Cathy Purdue made corn bread in are- Bigycles took on a strange appearance for the parade. flector oven. Cont'd on Page 12 . Cont'd on Page 12 I page 2 THE TOWN CRIER is published each Thursday qf[ilo· :e ·bH1ntUI1,ity evening by the TOWN CRIER PUBLICATIONS. We hope to be of help to the citizens of the·towns . ,. in our coverage through NEWS, INFORMATION, ~ocpit .~L ~~w,~ AND LOWER PRICED ADVERTISING. We accept no financial responsibility for errors A gHtoLi·t?-ference books for the Hospital Libr'1\r~ ~~ls been · re- in advertising but will gladly print corrections .. ceived fr'om -Roche Laboratories. · · · . C'opies of-most ph.otos appearing in THE TOWN " Rec,eptionists~\re: Friday, Hilda Brown:_S::!turclay ; Myra'!Vtul GRIER mav be obtained through our office. lenancl Susi\risturtevant; Sunday; Stephtfi'iie'Hc;\\ia rct .and 'Ev:\ j~e> • · ri· y~n1 have news or available photos of any sort gacy; Monday, Stephanie Sturt~vnnt; Tu(~sthy, Jun0 D;•·sh:•: ~\/(• ·. ! ~ we urge you to call an editor or drop in. _.Pead ne.sday, _Lottie Do en~: Thursday, Mu riel Ciui mb.v. · line will be Monday Noon but we would appreciate ADMISSIONS . -

Blackest Night / Brightest Day Jumpchain What Is Death in a World

Blackest Night / Brightest Day Jumpchain What is death in a world like this one? Great heroes and villains alike have tasted the sweet kiss of oblivion, both deserving and not. Yet death has also been defied, and many more have returned to life through circumstance or miracle. Two heroes in particular – Hal Jordan, a Green Lantern of Earth, and Barry Allen, The Flash, both ponder this together as they talk over the gravestone of Bruce Wayne. Both had died and returned to life before. And soon, many more will return as well...but not in a way they or anyone else would expect. Recently, the Green Lantern Corps, a peacekeeping organization created by the self-touted Guardians of the Universe, have been at war with the Sinestro Corps founded by its namesake rogue who fell from grace in the past. As this conflict raged on, other Lantern Corps were discovered or created as all seven colors on the Emotional Spectrum were revealed to the galaxy. But as this conflict and chaos rages on, a prophecy is fulfilled and as the various colors come into battle with each other, a darker force awakens. The Entity of Death, Nekron, acting through the villain Death’s Hand, has prepared to unleash a plague on the entire universe. One that will see the billions of dead across all of creation rise and seek to ravage the living, before extinguishing all life entirely within the Blackest Night. Just as this conversation began, you appear. You are a new or veteran member of one of the existing Lantern Corps...unless you are a Black Lantern, in which you rise from death not long after as the crisis of the Blackest Night begins. -

Hughes Denies Mafia Link

\ew Jersey Finally Starts War on Pollution STOKY PAGE 15 Sunny and Cold THEBAEY FINAL Partly sunny and cold today. Cloudy and colder again Red Bulk, Freehold tomorrow. I Long Branch 7 EDITION (Bit DetUIl, Put 3) Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 02 Years POL. 93, NO. 135 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JANUARY 8, 1970 26 PAGES 10 CENTS Hughes Denies Mafia Link By LEW HEAD Richard J. Hughes said in a four-year period, tell of ing received $10,000 per year —Former Essex County NEWARK (AP) - An an- wrathful reaction to a De- payoffs to public officials, in mob payoffs, said his on- Democratic leader Dennis gry denial of any association Carlo statement that "if loanSharking and gambling ly involvement with Mafia Carey, mentioned as a re- wiitih a reputed Mafia figure Hughes gets in (elected), operations, and name many figures has been on an "of- cipient of Mafia funds, was has been made by New Jer- we're all right." prominent personalities. ficial basis." He also as- reached in Florida for com- sey's governor — one of a "The unfortunate thing The transcripts .include serted that he successfully ment. He said he "never number of reactions yester- about tapes," the governor cautionary footnotes by the prosecuted Russo on perjury took a quarter." day by public officials to the said, "is that there is no FBI to the effect that those charges in 1963. Russo is ap- —Atlantic City Police Sgt. release of taped conversa- protection for innocent peo- bugged may be embellishing pealing. Anthony Pasquale, men- tion of underworld figures. -

Norman Liebmann Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8h99bfn No online items Norman Liebmann Papers Finding aid created by Writers Guild Foundation Archive staff using RecordEXPRESS Writers Guild Foundation Archive 7000 West Third Street Los Angeles, California 90048 (323) 782-4680 [email protected] https://www.wgfoundation.org/archive/ 2019 Norman Liebmann Papers WGF-MS-066 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Norman Liebmann Papers Dates: 1958-1996 Collection Number: WGF-MS-066 Creator/Collector: Liebmann, Norman, 1928-2010 Extent: 28.5 linear feet, 21 record boxes and 2 archival boxes Repository: Writers Guild Foundation Archive Los Angeles, California 90048 Abstract: The Norman Liebmann Collection consists of produced and unproduced television scripts, feature films, book manuscripts, short stories, and plays written by Liebmann. The highlight of the collection relates to development materials, drawings, notes, correspondence, contracts, synopses, outlines, scripts and press clippings for the television series The Munsters, which Liebman co-developed. In addition, the collection contains jokes, sketches and scripts for late-night and variety luminaries Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Gene Rayburn, Gene Kelly and Johnny Carson and scripts for popular shows like Chico and the Man and Good Times. Additional materials include pitch documents, outlines and scripts for unproduced TV series and films. Additionally, this collection includes unpublished book manuscripts, short stories, and plays. Language of Material: English Access Available by appointment only. Most materials stored offsite. One week advance notice required for retrieval. Publication Rights The responsibility to secure copyright and publication permission rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation Norman Liebmann Papers. Writers Guild Foundation Archive Acquisition Information Donated by wife Shirley Liebmann on January 29, 2016. -

Nixon Assures Israel of Peace Talks Safety

Black Leaders Rap Inaction by City SEE STORY BELOW Hot and Humid Warn' and humid, showers possible today and tonight. FINAL Hot and humid tomorrow, Red Bank, Freehold (Be* Eefalll. Pa.j. « Long Branch J EDITION Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years VOL'. 93, NO. 25 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, JULY 31, 1970 20 PAGES TEN CENTS Nixon Assures Israel Of Peace Talks Safety LOS ANGELES (AP)' — President Nixon has to have forced policy in this area," he said. "Our' unrest, "it is a problem which college adminis- given the Israel government his-personal assur- policy is one of cooperation rather than coercion." trators and college faculties must face up to." ance that entering Middle East talks, as he pro- ; SEES ECONOMIC UPSWING He. said he thought it "very short-sighted" for uni- posed, would not endanger Israel's military posi- , • —The economy will be "moving upward in the versity presidents and professors "to put the last half of 1970" with inflation being cooled. blame for all the problems of the universities on tion. • ••'.' the government." Nixon told a television-radio news conference However, he said, he may have to veto some popular bills if'Congress appropriates more than Nixon also was asked about statements by at the Century Plaza Hotel last night that he hopes his campus advisers that government should Israel will join Egypt and Jordan in accepting his he wants and a request for higher taxes would be used as a last resort to keep the federal budget recognize the reality of fears of repression among proposal for a 90-day cease-fire while negotiations under control. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

The Blackest Night for Aristotle's Account of Emotions

PART ON E WILL AND EMOTION: THE PHILOSOPHICAL SPECTRUM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CCH001.inddH001.indd 5 33/14/11/14/11 88:42:24:42:24 AAMM CCH001.inddH001.indd 6 33/14/11/14/11 88:42:24:42:24 AAMM THE BLACKEST NIGHT FOR ARISTOTLE’S ACCOUNT OF EMOTIONS Jason Southworth Since 2005’s Green Lantern: Rebirth, writer Geoff Johns has told a series of stories leading up to Blackest Night, introducing to the DC Universe a series of six previously unknown color corps in addition to the classic green: red (rage), orange (avarice), yellow (fear), blue (hope), indigo (compassion), and violet (love).1 The members of each corps see the emotion they represent as the most important one and believe that acting out of that emotion is the only appropriate way to behave. The Green Lanterns, on the other hand, represent the triumph of willpower or reason over emotion and seek to overcome and stifl e these emotional states.2 The confl ict between the various lantern corps, while provid- ing an interesting series of stories, also sets the stage for thinking about one of the most long-standing questions in ethics: What role should emotion play in moral reasoning? 7 CCH001.inddH001.indd 7 33/14/11/14/11 88:42:24:42:24 AAMM 8 JASON SOUTHWORTH Color-Coded Morality With the exception of the Indigo Lanterns (who don’t speak a language that can be translated by a Green Lantern power ring, much less your average comics reader), the representa- tives of the new color corps all make the case that acting out their sections of the emotional spectrum is the only way to achieve justice.