The Blackest Night for Aristotle's Account of Emotions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Green Lantern Corps: Reckoning Volume 6 Free

FREE GREEN LANTERN CORPS: RECKONING VOLUME 6 PDF Bernard Chang,Van Jensen | 144 pages | 28 Jul 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401254759 | English | United States Green Lantern Corps: Reckoning (Volume) - Comic Vine Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Green Lantern Corps, Vol. Green Lantern Corps, Vol. The Green Lantern Corps is one of the strongest forces in the universe-they have to be in order to keep the peace across thousands of space sectors. But there are powers beyond this universe, and beyond anything the Corps has ever encountered. The Green Lanterns have taken on tyrants and monsters before…but even they are no match for gods. The New Gods of New Genesis are l The Green Lantern Corps is one of the strongest forces in the universe-they have to be in order to keep the peace across thousands of space sectors. Now, to rally his Corps to victory, John Stewart will have to become something more than just a Green Lantern. Collects issues Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Green Lantern Corps: Reckoning Volume 6 Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Green Lantern Corps, Vol. Be the first to ask a question about Green Lantern Corps, Vol. Lists with This Book. -

741.5 Batman..The Joker

Darwyn Cooke Timm Paul Dini OF..THE FLASH..SUPERBOY Kaley BATMAN..THE JOKER 741.5 GREEN LANTERN..AND THE JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA! MARCH 2021 - NO. 52 PLUS...KITTENPLUS...DC TV VS. ON CONAN DVD Cuoco Bruce TImm MEANWHILE Marv Wolfman Steve Englehart Marv Wolfman Englehart Wolfman Marshall Rogers. Jim Aparo Dave Cockrum Matt Wagner The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of In celebration of its eighty- queror to the Justice League plus year history, DC has of Detroit to the grim’n’gritty released a slew of compila- throwdowns of the last two tions covering their iconic decades, the Justice League characters in all their mani- has been through it. So has festations. 80 Years of the the Green Lantern, whether Fastest Man Alive focuses in the guise of Alan Scott, The company’s name was Na- on the career of that Flash Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner or the futuristic Legion of Super- tional Periodical Publications, whose 1958 debut began any of the thousands of other heroes and the contemporary but the readers knew it as DC. the Silver Age of Comics. members of the Green Lan- Teen Titans. There’s not one But it also includes stories tern Corps. Space opera, badly drawn story in this Cele- Named after its breakout title featuring his Golden Age streetwise relevance, emo- Detective Comics, DC created predecessor, whose appear- tional epics—all these and bration of 75 Years. Not many the American comics industry ance in “The Flash of Two more fill the pages of 80 villains become as iconic as when it introduced Superman Worlds” (right) initiated the Years of the Emerald Knight. -

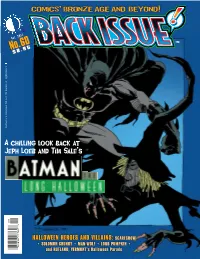

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

GREEN LANTERN the ANIMATED SERIES by - Manyfist in 2011 There Was a CGI Series That Aired on Cartoon Network

GREEN LANTERN THE ANIMATED SERIES By - Manyfist In 2011 there was a CGI series that aired on Cartoon Network. It was part their DC Nation block. You arrive when a certain human pilot is on Oa, about to skip half way across the universe in the experimental ship. While the storyline lasts only a year, there is still much untold stories to be told. As such your benefactor, had given you +1000cp (Choice Points) to help you on your journey to the frontier of the universe. LOCATION Unfortunately space is a vast place, and your choice of rings depend on where you start out at. Green On board the Interceptor sleeping as Hal & Kilowog steal it. Aya's scanners did not realize you were aboard until it was too late to turn around. Blue You're seeking hope on the planet called Mogo. This planet you're on, is a living planet who traps dangerous aliens and provides them with care. You were drawn in by accident really as your arrival was misinterpreted as a hostile force, however you'll find your brother lantern, Blue Lantern Saint Walker, here as well. Mogo has complete control over its bio dome, and as an apology Mogo will do anything in its power to help. Red Listening to a sermon of Rage onboard, the Shard. The Shard is the only piece of Atrocitus' home world which was destroyed by the Manhunters. Here he has built a religion around the incident and intends to wipe off the Guardians of the Universe from the cosmos in revenge. -

Selznick, Brian Boy of a Thousand Faces Juv

GRAPHIC NOVELS- PRESCHOOL, ELEMENTARY& MIDDLE SCHOOL compiled by Sheila Kirven HYBRID Preschool Alborough, Jez Yes Juv.A3397y Cordell, Matthew Wolf in the snow Juv.C7946w Haughton, Chris Shh! We have a plan Juv. H3717s McDonald, Ross Bad Baby Juv.M13575b (Jack has a new baby sister) Reynolds, Aaron Creepy Carrots Juv.R462c Rex, Adam Pssst! Juv.R4552p Rocco, John Blackout Juv.R6715b Willems, Mo That is not a good idea! Juv.W699t Vere, Ed Getaway Juv.V4893g Elementary Buzzeo, Toni One cool friend Juv. B9928o Chin, Jason Island: A Story of the Galapagos Juv.508.86.C539i Craft, Jerry Big Picture: Juv.C8856m What you need to succeed! Dauvillier, Loie hidden Juv.D2448 (A young French girl is hidden away during the Holocaust in France) DiCamilio, Kate Flora & Ulysses: Juv. D545f The Illuminated Adventures (Rescuing a squirrel after an accident involving a vacuum cleaner, comic-reading cynic Flora Belle Buckman is astonished when the squirrel, Ulysses, demonstrates astonishing powers of strength and flight after being revived.) Gaiman, Neil The day I swapped my Dad for two Juv.G141di goldfish Holub, Joan Little Red Writing Juv.H7589L (A brave little pencil attempting to write a story with a basket of parts of speech outwits the Wolf 3000 pencil sharpener and saves Principal Granny.) Lane, Adam J.B. Stop Thief Juv. L2652s Law, Felicia & Castaway Code: Sequencing in Action Juv.L4152c Way, Steve Law, Felicia & Crocodile teeth: Geometric Shapes Juv.L4152ct Way, Steve in Action Law, Felicia & Mirage in the Mist: Measurement Juv.L4152ct Way, Steve in Action Law, Felicia & Mystery of Nine: Number Place Juv.L4152mn Way, Steve and Value in Action Law, Felicia & Storm at Sea: Sorting, Mapping and Juv.L4152ct Way, Steve Grids in Action sdk 6/08 rev. -

1 the Flashes Collection

1 THE FLASHES COLLECTION 2 3 From the Risale-i Nur Collection The Flashes Collection Bediuzzaman Said Nursi 4 Translated from the Turkish ‘Lem’alar’ by Şükran Vahide 2009 Edition. Copyright © 2009 by Sözler Neşriyat A.Ş. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced by any means in whole or in part without prior written permission. For information, address: Sözler Neşriyat A.Ş., Nuruosmaniye Cad., Sorkun Han, No: 28/2, Cağaloğlu, Istanbul, Turkey. Tel: 0212 527 10 10; Fax: 0212 520 82 31 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.sozler.com.tr 5 Contents THE FIRST FLASH: An instructive explanation of the verse, “But he cried through the depths of the darkness…” the famous supplication of the Prophet Jonah (UWP), showing its relevance for everyone. 17 THE SECOND FLASH: The famous supplication of the Prophet Job (UWP), “When he called upon his Sustainer saying: ‘Verily harm has afflicted me…’” is expounded in five points, providing a true remedy for the disaster-struck. 21 THE THIRD FLASH: Three points expounding with the phrases “The Eternal One, He is the Eternal One!” two important truths contained in the verse, “Everything shall perish save His countenance…” 30 THE FOURTH FLASH: The Highway of the Practices of the Prophet (UWBP). This solves and elucidates with complete clarity one of the major points of conflict between the Sunnis and the Shi‘a, the question of the Imamate, and expounds two important verses in four points. 35 THE FIFTH FLASH is included in the Twenty-Ninth Flash. THE SIXTH FLASH is also included in the Twenty-Ninth Flash. -

Blackest Night / Brightest Day Jumpchain What Is Death in a World

Blackest Night / Brightest Day Jumpchain What is death in a world like this one? Great heroes and villains alike have tasted the sweet kiss of oblivion, both deserving and not. Yet death has also been defied, and many more have returned to life through circumstance or miracle. Two heroes in particular – Hal Jordan, a Green Lantern of Earth, and Barry Allen, The Flash, both ponder this together as they talk over the gravestone of Bruce Wayne. Both had died and returned to life before. And soon, many more will return as well...but not in a way they or anyone else would expect. Recently, the Green Lantern Corps, a peacekeeping organization created by the self-touted Guardians of the Universe, have been at war with the Sinestro Corps founded by its namesake rogue who fell from grace in the past. As this conflict raged on, other Lantern Corps were discovered or created as all seven colors on the Emotional Spectrum were revealed to the galaxy. But as this conflict and chaos rages on, a prophecy is fulfilled and as the various colors come into battle with each other, a darker force awakens. The Entity of Death, Nekron, acting through the villain Death’s Hand, has prepared to unleash a plague on the entire universe. One that will see the billions of dead across all of creation rise and seek to ravage the living, before extinguishing all life entirely within the Blackest Night. Just as this conversation began, you appear. You are a new or veteran member of one of the existing Lantern Corps...unless you are a Black Lantern, in which you rise from death not long after as the crisis of the Blackest Night begins. -

GREEN LANTERN the ANIMATED SERIES by - Manyfist in 2011 There Was a CGI Series That Aired on Cartoon Network

GREEN LANTERN THE ANIMATED SERIES By - Manyfist In 2011 there was a CGI series that aired on Cartoon Network. It was part their DC Nation block. You arrive when a certain human pilot is on Oa, about to skip half way across the universe in the experimental ship. While the storyline lasts only a year, there is still much untold stories to be told. As such your benefactor, had given you +1000cp (Choice Points) to help you on your journey to the frontier of the universe. LOCATION Unfortunately space is a vast place, and your choice of rings depend on where you start out at. Green On board the Interceptor sleeping as Hal & Kilowog steal it. Aya's scanners did not realize you were aboard until it was too late to turn around. Blue You're seeking hope on the planet called Mogo. This planet you're on, is a living planet who traps dangerous aliens and provides them with care. You were drawn in by accident really as your arrival was misinterpreted as a hostile force, however you'll find your brother lantern, Blue Lantern Saint Walker, here as well. Mogo has complete control over its bio dome, and as an apology Mogo will do anything in its power to help. Red Listening to a sermon of Rage onboard, the Shard. The Shard is the only piece of Atrocitus' home world which was destroyed by the Manhunters. Here he has built a religion around the incident and intends to wipe off the Guardians of the Universe from the cosmos in revenge. -

Green Lantern a Guide to Jordan Family Members and Their Appearances Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GREEN LANTERN A GUIDE TO JORDAN FAMILY MEMBERS AND THEIR APPEARANCES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Deborah Eker | 60 pages | 01 Jan 2018 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781983486579 | English | none Green Lantern A Guide to Jordan Family Members and Their Appearances PDF Book He was one of the first characters introduced during the company-wide relaunch when he appeared in the pages of the teaser comic The New 52 Free Comic Book Day Special Edition. Though after spending weeks in it, I'm ready to turn on the lights and scare the nightmares away. Three years after his father's death, Hal started dating a girl named Jennifer. Working together, the Lanterns drove Mongul into the local moon, where a major battle ensued. Upon arrival, the escort team is ambushed by the Sinestro Corps , and again later by the Red Lantern Corps. As Hal attempts to leave Parallax, Sinestro tells him it's his destiny to be the host and not Hal. Jordan and Kent would remain acquaintances. Enraged that the Guardians would ignore the personal loss he had suffered in the name of their Corps, Hal became insane with grief and decided to meat them head on and defeat the men who destroyed his life. So they decide to wait until the time is right. Showcase 22, Emerald Dawn 1 Hal would later learn that another man, Guy Gardner , was deemed equally worthy. A few nights later, Jordan's life was jeopardized by his lack of fear. While they're talking, the Shark leaps through the window intent on killing Hal Jordan. -

DC Comics Jumpchain CYOA

DC Comics Jumpchain CYOA CYOA written by [text removed] [text removed] [text removed] cause I didn’t lol The lists of superpowers and weaknesses are taken from the DC Wiki, and have been reproduced here for ease of access. Some entries have been removed, added, or modified to better fit this format. The DC universe is long and storied one, in more ways than one. It’s a universe filled with adventure around every corner, not least among them on Earth, an unassuming but cosmically significant planet out of the way of most space territories. Heroes and villains, from the bottom of the Dark Multiverse to the top of the Monitor Sphere, endlessly struggle for justice, for power, and for control over the fate of the very multiverse itself. You start with 1000 Cape Points (CP). Discounted options are 50% off. Discounts only apply once per purchase. Free options are not mandatory. Continuity === === === === === Continuity doesn't change during your time here, since each continuity has a past and a future unconnected to the Crises. If you're in Post-Crisis you'll blow right through 2011 instead of seeing Flashpoint. This changes if you take the relevant scenarios. You can choose your starting date. Early Golden Age (eGA) Default Start Date: 1939 The original timeline, the one where it all began. Superman can leap tall buildings in a single bound, while other characters like Batman, Dr. Occult, and Sandman have just debuted in their respective cities. This continuity occurred in the late 1930s, and takes place in a single universe.