Stewart Lloyd Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

0.5 Km 2 Km 82 Km 91 Km RICE RIVER ROAD 132 Km 16 Km 285 Km 222

-97° -96° Lake -95° ot -94° rr l Walker Ca il H Brown Lake Cross Lake Lake r Wanless e Windy Rat k First Nation Lake Gods Lake c Cross Lake Lake Lake u ne . S pi R 199 km cu Gods Lake or Munro Lake 49 km P Opiminegoka God's Lake Narrows Lake n Narrows Laidlaw Cole Max Lakes First Nation Knife Lake 374 Lake Touchwood Lawford Lake 31 km s Pipestone Lake Aswapiswanan od Webber Lake Butterfly G L. Logan Lake Lake Lake 41 km Murray Sharpe Ec Lake Lake himamish Lake 0.5 km R. Joint Hayes Lake Kanuchuan Robinson Lake . Hairy Lake Rapids 74 km R Goose Lake Portage green er Hill Beav Rochon L. d eca olie e Lake Bolton Kalli ho Lake Lake R L. Lake Red Sucker L Cr. Molson Lake Little Bolton irst Nation Red F usk 373 Paim Sucker Lake Red Sucker Lak Lake Kennedy Lake . n R o s l k e or N Norway 11 km Y House Chapin Cree Nation Fairy Rock Bay Hilton Lake 54° orway House Lake M n Hill 54° o Garde Ridge l McGowan s Krolman Rossville o First Nation L. n Lake y Lake Willow e Ba Wabisi Lake ran R. 222 km Beach Waasagomach och York Angling Stevenson C Lake Lake . Washahigan Lake R Wasagamack L. Lake L. Pakatawacun First Nation Garden Hill Lake Island Lake ke McL Mercer Ponask Begg au d ghl Costes Lake Pelican n in Lake Lone a Lake St. Theresa Point l ewan R Lake n Island Sagawitch L. -

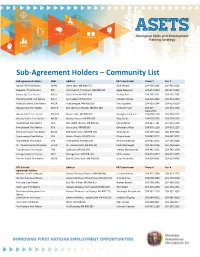

Sub-‐Agreement Holders – Community List

Sub-Agreement Holders – Community List Sub-Agreement Holders Abbr. Address E&T Coordinator Phone # Fax # Garden Hill First Nation GHFN Island Lake, MB R0B 0T0 Elsie Monias 204-456-2085 204-456-9315 Keewatin Tribal Council KTC 23 Nickel Rd, Thompson, MB R8N 0Y4 Aggie Weenusk 204-677-0399 204-677-0257 Manto Sipi Cree Nation MSCN God's River, MB R0B 0N0 Bradley Ross 204-366-2011 204-366-2282 Marcel Colomb First Nation MCFN Lynn Lake, MB R0B 0W0 Noreena Dumas 204-356-2439 204-356-2330 Mathias Colomb Cree Nation MCCN Pukatawagon, MB R0B 1G0 Flora Bighetty 204-533-2244 204-553-2029 Misipawistik Cree Nation MCN'G Box 500 Grand Rapids, MB R0C 1E0 Melina Ferland 204-639- 204-639-2503 2491/2535 Mosakahiken Cree Nation MCN'M Moose Lake, MB R0B 0Y0 Georgina Sanderson 204-678-2169 204-678-2210 Norway House Cree Nation NHCN Norway House, MB R0B 1B0 Tony Scribe 204-359-6296 204-359-6262 Opaskwayak Cree Nation OCN Box 10880 The Pas, MB R0B 2J0 Joshua Brown 204-627-7181 204-623-5316 Pimicikamak Cree Nation PCN Cross Lake, MB R0B 0J0 Christopher Ross 204-676-2218 204-676-2117 Red Sucker Lake First Nation RSLFN Red Sucker Lake, MB R0B 1H0 Hilda Harper 204-469-5042 204-469-5966 Sapotaweyak Cree Nation SCN Pelican Rapids, MB R0B 1L0 Clayton Audy 204-587-2012 204-587-2072 Shamattawa First Nation SFN Shamattawa, MB R0B 1K0 Jemima Anderson 204-565-2041 204-565-2606 St. Theresa Point First Nation STPFN St. Theresa Point, MB R0B 1J0 Curtis McDougall 204-462-2106 204-462-2646 Tataskweyak Cree Nation TCN Split Lake, MB R0B 1P0 Yvonne Wastasecoot 204-342-2951 204-342-2664 -

COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing

CANADIANCCPA CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES MANITOBA COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing “Wash hands frequently” and “Self-isolate” Akin to “Let them eat cake” in First Nations with Overcrowded Homes Lacking Piped Water By Shirley Thompson, Marleny Bonnycastle and Stewart Hill MAY 2020 COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing: About the Authors “Wash hands frequently” and “Self-isolate” Marleny M. Bonnycastle is an Associate Professor at Akin to “Let them eat cake” in First Nations with the University of Manitoba, Faculty of Social Work in Overcrowded Homes Lacking Piped Water Winnipeg and worked for five years at the Northern isbn 978-1-77125-505-9 Social Work Program. During that time, Marleny developed relationships with northern communities May 2020 that contributed to the development of her research. Currently, Marleny is a co-researcher of the Mino Bimaadiziwin partnership. She is also a research This report is available free of charge from the CCPA associate with the Canadian Centre for Policy website at www.policyalternatives.ca. Printed Alternatives – Manitoba. copies may be ordered through the Manitoba Office for a $10 fee. Stewart Hill is a PhD Candidate at the Natural Resources Institute who is also working as a Senior Research and Policy Analyst at the Manitoba Help us continue to offer our publications free online. Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO), the Manitoba We make most of our publications available free northern Chiefs organization. Mr. Hill is from the on our website. Making a donation or taking out a God’s Lake First Nation, and was born and raised membership will help us continue to provide people in northern Manitoba at God’s Lake, and is able to with access to our ideas and research free of charge. -

Project 6 - All-Season Road Linking Manto Sipi Cree Nation, Bunibonibee Cree Nation & God’S Lake First Nation

PROJECT 6 - ALL-SEASON ROAD LINKING MANTO SIPI CREE NATION, BUNIBONIBEE CREE NATION & GOD’S LAKE FIRST NATION ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT SCOPING DOCUMENT PREPARED FOR: ENVIRONMENTAL APPROVALS BRANCH MANITOBA SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT MAY 2017 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of Scoping Document ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Regulatory Framework .................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Scope of Project and Assessment ................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Scope of Project ............................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Scope of Assessment ....................................................................................................................................... 2 3 Engagement .................................................................................................................................................. 3 3.1 Objectives ....................................................................................................................................................... -

![The I]Niversity of Manitoba Rubidiiim-Strontiim I^Ihole-Rock Ages Sha-Pak Cheung Submitted to the Faciilty of Graduate Studies I](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0708/the-i-niversity-of-manitoba-rubidiiim-strontiim-i-ihole-rock-ages-sha-pak-cheung-submitted-to-the-faciilty-of-graduate-studies-i-2200708.webp)

The I]Niversity of Manitoba Rubidiiim-Strontiim I^Ihole-Rock Ages Sha-Pak Cheung Submitted to the Faciilty of Graduate Studies I

THE I]NIVERSITY OF MANITOBA RUBIDIIIM-STRONTIIM I^IHOLE-ROCK AGES FROM THE OXFORD LAKE _ KNEE LAKE GRNENSTONE BELT, NORTHERN I'IANITOBA BY SHA-PAK CHEUNG A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACIILTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PART]AL FULFILMENT OF TIIE REQUIREMENTS FOR TTIE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES I^IINNIPEG, MANITOBA oCTOBER, 1g7B RUBIDIUM-STRONTIUM I.IHOLE-ROCK AGES FROM THE OXFORD LAKE - KNEE LAKE GREENSTONE BELT, NORTHER.N PIAN ITOBA BY SHA-PAK CHEUNG A dissertution submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies <¡f ttre University of Manitobu in purtial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCT @ r-t 978 Per¡¡¡ission hus becn grantcd to the LIBRARY OF THtj UNIVUR. SITY OF MANITOIIA tt¡ lcnd or scll copies of this dissertation, to the NATIONAL LIBRARY Ot¡ CANADA to nricrotilm this dissertution and to lend or sell copics of the filnr, and UNtVERStTy N{lCROFl¡-MS to publish an ubstract of this dissertation. Thc autlrt¡r reserves other publicutit¡n rights, and neitl¡cr the dissertation nor extcnsivc cxtructs from it uray be printed or other- wise reproducecl without tlrr: i¡utl¡or's writtcu pcnnission. ABSTRACT Rubidium-strontium whole rock ages have been determined on rock units from the Oxford Lake-Knee Lake greenstone belt within the Superior Province in norËheastern Manitoba. The Magíll Lake PluËon, a post-oxford Lake Group granitic intru- 87*b sion gave an age of 2455+ 35 Ma (À = L.42 x 10-11 yr.-l¡ "rrd 9,7 9, an ínitial "'sr/""sr ratio of 0.lo7ï+ 0.0043. -

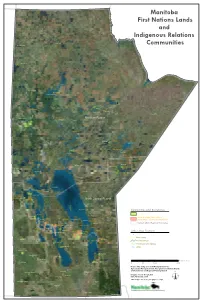

Manitoba First Nations Lands and Indigenous Relations Communities

60N Manitoba First Nations Lands and 59N Indigenous Relations Sayisi Dene Northlands Dene Communities 89W 58N Barren Lands Brochet 57N Marcel Colomb South Indian Lake O-Pipon-Na-Piwin 90W Gillam Tataskweyak Granville Lake Ilford War Lake York Factory 56N Fox Lake Shamattawa Nelson House Mathias Colomb Northern Region Nisichawayasihk !Thompson Pikwitonei Thicket Portage Sherridon 55N Oxford House Wabowden Bunibonibee Manto Sipi Flin !Flon 102W Herb Lake Landing Gods Lake Narrows 93W 92W 91W Cross Lake 96W 95W 94W 97W 99W 98W 101W 100W God's Lake Cross Lake Red Sucker Lake Cormorant Red Sucker Lake Garden Hill Norway House 54N Wasagamack Opaskwayak Norway House Island Lake The Pas Mosakahiken St. Theresa Point Moose Lake Misipawistik Easterville Chemawawin 53N Dawson Bay Poplar River Red Deer Lake Barrows Sapotaweyak Powell National Mills Baden Pelican Rapids North Central Region Wuskwi Sipihk Berens River Berens River Communities and Boundaries Pauingassi Duck Bay First Nations Lands Pine Creek Little Grand Rapids 52N Little Grand Rapids Northern Affairs Communities Skownan Mallard Camperville Dauphin River Dauphin River Jackhead (Indigenous Relations Communities) Rock Ridge Princess Harbour Waterhen Bloodvein Northern Affairs Regional Boundaries Salt Point Homebrook - Peonan Point Lake St. Martin Matheson Island Little Saskatchewan Pine Dock Meadow Portage Spence Lake Pinaymootang Loon Straits Dallas / Red Rose Fisher Bay Crane River O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi Other Map Features Fisher River ! Harwill Cities Peguis Aghaming Expressway Valley -

Winter Roads in Manitoba

CGU HS Committee on River Ice Processes and the Environment 12th Workshop on the Hydraulics of Ice Covered Rivers Edmonton, AB, June 19-20, 2003 Winter Roads in Manitoba Don Kuryk Department of Transportation & Government Services 16th Floor – 215 Garry Street Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3C 3Z1 [email protected] Winter roads have connected isolated northern communities for over 50 years. Originally, winter roads were constructed by private contractors. Since 1979, the Department of Transportation has been overseeing the construction and maintenance of winter roads through contracts with Indian Bands and other local groups. The winter road network in Manitoba spans a length of 2178 km and services 30 communities (approximately 29000 people). It is extremely important for the shipment of goods, employment of locals and travel between communities. With the certainty of climate change and expected temperature increases of 4-6°C by the end of this century, there is a real threat to the seasonal operation of winter roads. The inevitable climate change from greenhouse gas emissions will result in later freeze-ups, earlier spring melts and more frost-free days. The implications of this climate change would be detrimental to the winter road network. An example of these implications was the airlifts required in 1998 to transport essential supplies to several communities as a result of drastic changes in the climate predominately due to El Nino. This shortened the winter road season and didn’t allow some of the routes to be constructed at all. 1. Introduction Winter roads originated over 50 years ago as a private operation until the government took over the network in 1971. -

Local and Regional Identity Action Plan

LLOCALOCAL AANDND RREGIONALEGIONAL IIDENTITYDENTITY AACTIONCTION PPLANLAN TTHEHE TTHOMPSONHOMPSON EECONOMICCONOMIC DDIVERSIFICATIONIVERSIFICATION WWORKINGORKING GGROUPROUP CCONSULTATIONONSULTATION SUMMARYSUMMARY REPORTREPORT JanuaryJanuary 20132013 THE THOMPSON ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION WORKING GROUP 2 | The City of Thompson | Keewatin Tribal Council | The Manitoba Metis Federation | Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak | Thompson Unlimited ACTION PLAN #4: LOCAL AND REGIONAL IDENTITY - CONSULTATION SUMMARY REPORT LLOCALOCAL AANDND RREGIONALEGIONAL IIDENTITYDENTITY AACTIONCTION PPLANLAN | 3 TTHEHE TTHOMPSONHOMPSON EECONOMICCONOMIC DDIVERSIFICATIONIVERSIFICATION WWORKINGORKING GGROUPROUP CCONSULTATIONONSULTATION SUMMARYSUMMARY REPORTREPORT JanuaryJanuary 20132013 AActionProvincection of ManitobaPPlanlan ##4: |4 Northern: LLocaloc aAssociationl aandnd RRegionalof eCommunitygional Councils IIdentityden t| i tNisichawayasihky - CConsultationonsu Creelta tNationion |SSummary Thompsonumma Chamberry RReporte ofp oCommerrt ce | Vale Supported by: CITY THOMPSON (CHAIR) UNLIMITED PROVINCE of MANITOBA THOMPSON CHAMBER OF COMMERCE FEDERAL THOMPSON GOVERNMENT VALE ECONOMIC MKO UNITED DIVERSIFICATION STEEL WORKERS LOCAL 6166 WORKING GROUP KTC rePLAN MMF NCN Working Group Members NACC Invited Stakeholders THE THOMPSON ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION WORKING GROUP The City of Thompson | Keewatin Tribal Council | The Manitoba Metis Federation | Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak | Thompson Unlimited ACTION PLAN #4: LOCAL AND REGIONAL IDENTITY - CONSULTATION SUMMARY REPORT -

First Nations "! Lake Wasagamack P the Pas ! (# 297) Wasagamack First Nationp! ! ! Mosakahiken Cree Nation P! (# 299) Moose Lake St

102° W 99° W 96° W 93° W 90° W Tatinnai Lake FFiirrsstt NNaattiioonnss N NUNAVUT MMaanniittoobbaa N ° ° 0 0 6 6 Baralzon Lake Nueltin Kasmere Lake Lake Shannon Lake Nejanilini Lake Egenolf Munroe Lake Bain Lake Lake SASKATCHEWAN Northlands Denesuline First Nation (# 317) Shethanei Lake ! ! Sayisi Dene ! Churchill Lac Lac Brochet First Nation Brochet Tadoule (# 303) Lake Hudson Bay r e iv Barren Lands R (# 308) North ! Brochet Knife Lake l Big Sand il Etawney h Lake rc u Lake h C Buckland MANITOBA Lake Northern Southern Indian Lake Indian Lake N N ° ° 7 7 5 Barrington 5 Lake Gauer Lake Lynn Lake er ! Riv ! South Indian Lake n Marcel Colomb First Nation ! o O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation ls (# 328) e (# 318) N Waskaiowaka Lake r Fox Lake e Granville Baldock v ! (# 305) i Lake Lake ! R s Leaf Rapids e Gillam y Tataskweyak Cree Nation a P! H (# 306) Rat P! War Lake Lake Split Lake First Nation (# 323) Shamattawa ! ! York Factory ! First Nation Mathias Colomb Ilford First Nation (# 304) York (# 307) (# 311) Landing ! P! Pukatawagan Shamattawa Nelson House P!" Thompson Nisichawayasihk " Cree Nation Partridge Crop (# 313) Lake Burntwood Lake Landing Lake Kississing Lake Atik Lake Setting Sipiwesk Semmens Lake Lake Lake Bunibonibee Cree Nation Snow Lake (# 301) Flin Flon ! P! Manto Sipi Cree Nation P! Oxford Oxford House (# 302) Reed Lake ! Lake Wekisko Lake Walker Lake ! God's ! Cross Lake Band of Indians God's Lake First Nation Lake (# 276) (# 296) !P Lawford Gods Lake Cormorant Hargrave Lake Lake Lake Narrows Molson Lake Red Sucker Lake N N (# 300) ° ° 4 ! Red Sucker Lake ! 4 Beaver 5 Hill Lake 5 Opaskwayak Cree Nation Norway House Cree Nation (# 315) Norway House P!! (# 278) Stevenson Garden Hill First Nations "! Lake Wasagamack P The Pas ! (# 297) Wasagamack First NationP! ! ! Mosakahiken Cree Nation P! (# 299) Moose Lake St. -

Northern Healthy Foods Initiative Introduction This Report Describes the Northern Healthy Foods Initiative (NHFI) and Its Accomplishments to Date

Northern Healthy Foods Initiative Introduction This report describes the Northern Healthy Foods Initiative (NHFI) and its accomplishments to date. The NHFI provides funding for local and regional food system projects in northern Manitoba. The projects are developed and operated by local governments, community and youth groups, First Nation communities, private sector and community based organizations. History In 2003, the Healthy Child Committee of Cabinet mandated a study on the high costs of northern food prices. In August 2004, the Northern Food Prices Report was publicly distributed (www.gov.mb.ca/ana/food_ prices/2003_northern_food_prices_report.pdf ). The report identified seven options for addressing the high cost of food in northern Manitoba. With a primary focus on community-based projects in remote northern communities lacking all-weather road access, NHFI concentrates on food self-sufficiency projects like community foods programs, greenhouse pilot projects, northern gardens and food business development. In the lead up to permanent operations, grants were given to three regional organizations: Northern Association of Community Councils Inc., Bayline Regional Roundtable Inc. and Four Arrows Regional Health Authority Inc. Given that these three organizations serve a good number of small and large, road access and remote on and off reserve communities, they became the primary service/project delivery vehicles for the NHFI. On April 1, 2010 Food Matters Manitoba (formerly the Manitoba Food Charter) was added as a partner to serve