Winter Roads in Manitoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stewart Lloyd Hill

The Autoethnography of an Ininiw from God’s Lake, Manitoba, Canada: First Nation Water Governance Flows from Sacred Indigenous Relationships, Responsibilities and Rights to Aski by Stewart Lloyd Hill A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Natural Resources and Environmental Management Natural Resources Institute University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Copyright © 2020 by Stewart Lloyd Hill Abstract The Ininiw of Manitou (God's) Sakahigan (Lake), now known as God's Lake First Nation (GLFN), are an Indigenous people of Turtle Island, now called North America. As a GLFN Ininiw, I tell my autoethnography, drawing on a half-century of experience, both personal and professional, as well as a literature review, government data, and fieldwork. The medicine wheel framework required that I consider the spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental aspects of GLFN's water governance. I applied another Medicine wheel teaching regarding the Indigenous learning process to analyze this data, which provided an analytical framework to systematically process the data through heart, mind, body, and spirit. This thesis provides abundant evidence that the Ininiw of GLFN did not "cede or surrender" water governance in their traditional territory. Living in a lake environment, the GLFN Ininiw have survived, lived, thrived, and governed the aski (land and water) granted by Manitou (Creator) for thousands of years according to natural law. Through Ininiw governance, we kept God's Lake pristine. As GLFN Ininiw people's Aboriginal and treaty rights to govern over the waters of our ancestral lands were never surrendered, the GLFN Ininiw hold this governance still. -

Northeast Wollaston Lake Project: Quaternary Investigations of The

Northeast Wollaston Lake Project: Quaternary Investigations of the Cochrane River (NTS map sheets 64L-10, -11, -14, and -15) and Charcoal Lake (NTS map sheets 64L-9 and -16) Areas J.S. Smith Smith, J.S. (2006): Northeast Wollaston Lake Project: Quaternary investigations of the Cochrane River (NTS map sheets 64L- 10, -11, -14, and -15) and Charcoal Lake (NTS map sheets 64L-9 and -16) areas; in Summary of Investigations 2006, Volume 2, Saskatchewan Geological Survey, Sask. Industry Resources, Misc. Rep. 2006-4.2, CD-ROM, Paper A-6, 15p. Abstract Quaternary geological investigations were initiated in the Cochrane River–Charcoal Lake area (NTS map sheets 64L-9 -10, -11, -14, -15, and -16) as part of the multidisciplinary, multi-year Wollaston Lake Project. The Quaternary component involves 1:50 000-scale surficial geological mapping, collection of ice-flow indicators, and a regional till sampling program. Drift cover is extensive and includes till, organics, and glaciofluvial terrains as the main surficial units. Glacial landforms include hummocky stagnant ice-contact drift, thick blankets and plains, streamlined forms, and boulder fields. Large esker systems extend over the entire map area. These features are attributed to a slowly retreating ice margin, at which there was an abundance of meltwater that flowed both in channels and occasionally as turbulent sheet flows. Multiple ice-flow directions were documented; however, the ice-flow history remains preliminary as age relationships were only identified at five sites. The main regional ice flow was towards the south-southwest (207º). Initial flow ranged between the west-southwest to southwest (258º to 235º), and was followed by a southward (190º) flow before the main flow was established. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a Foundation in Northern Manitoba

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba Karla Zubrycki Dimple Roy Hisham Osman Kimberly Lewtas Geoffrey Gunn Richard Grosshans © 2014 The International Institute for Sustainable Development © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development | IISD.org November 2016 Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development International Institute for Sustainable Development The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is one Head Office of the world’s leading centres of research and innovation. The Institute provides practical solutions to the growing challenges and opportunities of 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 integrating environmental and social priorities with economic development. Winnipeg, Manitoba We report on international negotiations and share knowledge gained Canada R3B 0T4 through collaborative projects, resulting in more rigorous research, stronger global networks, and better engagement among researchers, citizens, Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 businesses and policy-makers. Website: www.iisd.org Twitter: @IISD_news IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and from the Province -

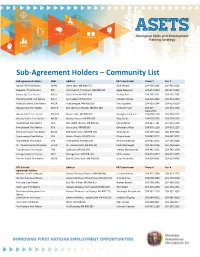

Sub-‐Agreement Holders – Community List

Sub-Agreement Holders – Community List Sub-Agreement Holders Abbr. Address E&T Coordinator Phone # Fax # Garden Hill First Nation GHFN Island Lake, MB R0B 0T0 Elsie Monias 204-456-2085 204-456-9315 Keewatin Tribal Council KTC 23 Nickel Rd, Thompson, MB R8N 0Y4 Aggie Weenusk 204-677-0399 204-677-0257 Manto Sipi Cree Nation MSCN God's River, MB R0B 0N0 Bradley Ross 204-366-2011 204-366-2282 Marcel Colomb First Nation MCFN Lynn Lake, MB R0B 0W0 Noreena Dumas 204-356-2439 204-356-2330 Mathias Colomb Cree Nation MCCN Pukatawagon, MB R0B 1G0 Flora Bighetty 204-533-2244 204-553-2029 Misipawistik Cree Nation MCN'G Box 500 Grand Rapids, MB R0C 1E0 Melina Ferland 204-639- 204-639-2503 2491/2535 Mosakahiken Cree Nation MCN'M Moose Lake, MB R0B 0Y0 Georgina Sanderson 204-678-2169 204-678-2210 Norway House Cree Nation NHCN Norway House, MB R0B 1B0 Tony Scribe 204-359-6296 204-359-6262 Opaskwayak Cree Nation OCN Box 10880 The Pas, MB R0B 2J0 Joshua Brown 204-627-7181 204-623-5316 Pimicikamak Cree Nation PCN Cross Lake, MB R0B 0J0 Christopher Ross 204-676-2218 204-676-2117 Red Sucker Lake First Nation RSLFN Red Sucker Lake, MB R0B 1H0 Hilda Harper 204-469-5042 204-469-5966 Sapotaweyak Cree Nation SCN Pelican Rapids, MB R0B 1L0 Clayton Audy 204-587-2012 204-587-2072 Shamattawa First Nation SFN Shamattawa, MB R0B 1K0 Jemima Anderson 204-565-2041 204-565-2606 St. Theresa Point First Nation STPFN St. Theresa Point, MB R0B 1J0 Curtis McDougall 204-462-2106 204-462-2646 Tataskweyak Cree Nation TCN Split Lake, MB R0B 1P0 Yvonne Wastasecoot 204-342-2951 204-342-2664 -

Recording the Reindeer Lake

CONTEXTUALIZING THE REINDEER LAKE ROCK ART A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Perry Blomquist © Copyright Perry Blomquist, April 2011. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5B1 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i ABSTRACT The rock art that is found in the region of Reindeer Lake, Saskatchewan is part of a larger category of rock art known as the Shield Rock Art Tradition. -

CIUR-FM Winnipeg – Licence Renewals

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2015-261 PDF version Reference: 2015-52 Ottawa, 18 June 2015 Native Communication Inc. Thompson and Winnipeg, Manitoba Applications 2014-0923-5 and 2014-0928-5, received 10 and 11 September 2014 CINC-FM Thompson and its transmitters; CIUR-FM Winnipeg – Licence renewals The Commission renews the broadcasting licences for the Type B Native radio stations CINC-FM Thompson and its transmitters, and CIUR-FM Winnipeg, from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2022. Introduction 1. Native Communication Inc. filed applications to renew the broadcasting licences for the following Type B Native radio stations, which expire 31 August 2015. Application Call sign and location number 2014-0923-5 CINC-FM Thompson, Manitoba, and its transmitters CICP-FM Cranberry Portage CIFF-FM Flin Flon CINR-FM Norway House CISI-FM South Indian Lake CIST-FM St. Theresa Point CISV-FM Swan River CITP-FM The Pas Indian Reserve CIWM-FM Brandon CIWR-FM Waterhen VF2106 Lac Brochet VF2107 Poplar River VF2108 Red Sucker Lake VF2109 Tadoule Lake VF2167 Pukatawagan VF2168 Wabowden VF2174 Gods Lake Narrows VF2175 God’s River VF2195 Cross Lake VF2196 Berens River VF2198 Garden Hill VF2199 Shamattawa VF2220 Brochet VF2222 Nelson House VF2261 Cormorant VF2262 Duck Bay VF2263 Grand Rapids VF2264 Pikwitonei VF2265 Split Lake VF2312 Churchill VF2313 Moose Lake VF2314 Oxford House VF2333 Gillam VF2334 Fox Lake, Alberta VF2335 Lake Manitoba VF2336 Griswold VF2337 Easterville VF2338 Thicket Portage VF2339 Bloodvein VF2340 Hollow Water First Nations VF2342 Sherridon VF2382 Long Plain VF2404 Jackhead VF2405 Pauingassi First Nation VF2406 Leaf Rapids VF2407 Little Grand Rapids VF2420 Camperville VF2421 Dauphin River VF2422 Ilford VF2423 Lynn Lake VF2462 Snow Lake VF2503 Fisher River VF2504 Paint Lake 2014-0928-5 CIUR-FM Winnipeg, Manitoba 2. -

Aqhaliat-2018-EN-Full-Report.Pdf

POLAR KNOWLEDGE Aqhaliat Table of Contents ECOSYSTEM SCIENCE .....................................................................................................1 Lichens in High Arctic ecosystems: Recommended research directions for assessing diversity and function near the Canadian High Arctic Research Station, Cambridge Bay, Nunavut ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Vascular synphenology of plant communities around Cambridge Bay, Victoria Island, Nunavut, during the growing season of 2015 .............................................................................. 9 The distribution and abundance of parasites in harvested wildlife from the Canadian North: A review .......................................................................................................................... 20 Fire in the Arctic: The effect of wildfire across diverse aquatic ecosystems of the Northwest Territories ................................................................................................................. 31 Arctic marine ecology benchmarking program: Monitoring biodiversity using scuba ............... 39 For more information about Polar Knowledge Canada, or for additional copies of this report, contact: Stratification in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago’s Kitikmeot Sea: Biological and geochemical consequences ........................................................................................................ 46 Polar Knowledge -

Phase 1 Geoscientific Desktop Preliminary Assessment, Terrain and Remote Sensing Study

Phase 1 Geoscientific Desktop Preliminary Assessment, Terrain and Remote Sensing Study NORTHERN VILLAGE OF PINEHOUSE, SASKATCHEWAN APM-REP-06144-0060 NOVEMBER 2013 This report has been prepared under contract to the NWMO. The report has been reviewed by the NWMO, but the views and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the NWMO. All copyright and intellectual property rights belong to the NWMO. For more information, please contact: Nuclear Waste Management Organization 22 St. Clair Avenue East, Sixth Floor Toronto, Ontario M4T 2S3 Canada Tel 416.934.9814 Toll Free 1.866.249.6966 Email [email protected] www.nwmo.ca PHASE 1 DESKTOP GEOSCIENTIFIC PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT TERRAIN AND REMOTE SENSING STUDY NORTHERN VILLAGE OF PINEHOUSE, SASKATCHEWAN November 2013 Prepared for: G.W. Schneider, M.Sc., P.Geo. Golder Associates Ltd. 6925 Century Ave, Suite 100 Mississauga, Ontario Canada L5N 7K2 Nuclear Waste Management Organization 22 St. Clair Avenue East 6th Floor Toronto, Ontario Canada M4T 2S3 NWMO Report Number: APM-REP-06144-0060 Prepared by: D.P. van Zeyl, M.Sc. L.A. Penner, M.Sc., P.Eng., P.Geo. J.D. Mollard and Associates (2010) Limited 810 Avord Tower, 2002 Victoria Avenue Regina, Saskatchewan Canada S4P 0R7 Terrain Report, Pinehouse, Saskatchewan November 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In March 2012, the Northern Village of Pinehouse, Saskatchewan, expressed interest in continuing to learn more about the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) nine-step site selection process, and requested that a preliminary assessment be conducted to assess the potential suitability of the Pinehouse area for safely hosting a deep geological repository (Step 3). -

Far North Geomapping Initiative: Bedrock Geology of the Snyder Lake Area, Northwestern Manitoba (Part of NTS 64N5) by P.D

GS-1 Far North Geomapping Initiative: bedrock geology of the Snyder Lake area, northwestern Manitoba (part of NTS 64N5) by P.D. Kremer, C.O. Böhm and N. Rayner1 Kremer, P.D., Böhm, C.O. and Rayner, N. 2011: Far North Geomapping Initiative: bedrock geology of the Snyder Lake area, northwestern Manitoba (part of NTS 64N5); in Report of Activities 2011, Manitoba Innovation, Energy and Mines, Manitoba Geological Survey, p. 6–17. Summary The Wollaston Domain, The Manitoba Geological Survey’s Far North Geo- which forms part of the base- mapping Initiative continued in the summer of 2011 with ment sequence to the Proterozoic bedrock and surfi cial geological mapping in the Snyder Athabasca Basin in northeastern Lake area, in the northwestern corner of the province. Saskatchewan, locally contains basement-hosted uncon- The Snyder Lake area is largely underlain by medium- formity-related world-class uranium deposits (e.g., Mil- to upper-amphibolite–grade metasedimentary rocks of lennium deposit). A number of uranium occurrences in the Wollaston Supergroup, including psammitic, semi- Saskatchewan are associated with particular strata of the pelitic, pelitic, and lesser amounts of calcsilicate gneiss Wollaston Supergroup (e.g., graphitic pelite of the Daly and marble. Southeast and northwest of Snyder Lake, the Lake Group, calcsilicate and calcareous arkose of the sedimentary succession is fl anked by intrusive rocks of Geikie River Group, Yeo and Delaney, 2007). As a result, potential Archean age that were metamorphosed at upper the Wollaston Domain in northwestern Manitoba has seen a recent increase in exploration activity. Regional map- amphibolite- to granulite-facies conditions. -

COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing

CANADIANCCPA CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES MANITOBA COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing “Wash hands frequently” and “Self-isolate” Akin to “Let them eat cake” in First Nations with Overcrowded Homes Lacking Piped Water By Shirley Thompson, Marleny Bonnycastle and Stewart Hill MAY 2020 COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing: About the Authors “Wash hands frequently” and “Self-isolate” Marleny M. Bonnycastle is an Associate Professor at Akin to “Let them eat cake” in First Nations with the University of Manitoba, Faculty of Social Work in Overcrowded Homes Lacking Piped Water Winnipeg and worked for five years at the Northern isbn 978-1-77125-505-9 Social Work Program. During that time, Marleny developed relationships with northern communities May 2020 that contributed to the development of her research. Currently, Marleny is a co-researcher of the Mino Bimaadiziwin partnership. She is also a research This report is available free of charge from the CCPA associate with the Canadian Centre for Policy website at www.policyalternatives.ca. Printed Alternatives – Manitoba. copies may be ordered through the Manitoba Office for a $10 fee. Stewart Hill is a PhD Candidate at the Natural Resources Institute who is also working as a Senior Research and Policy Analyst at the Manitoba Help us continue to offer our publications free online. Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO), the Manitoba We make most of our publications available free northern Chiefs organization. Mr. Hill is from the on our website. Making a donation or taking out a God’s Lake First Nation, and was born and raised membership will help us continue to provide people in northern Manitoba at God’s Lake, and is able to with access to our ideas and research free of charge.