COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indicators of Northern Health: a Resource for Northern Manitobans and the Bayline Regional Round Table

INDICATORS OF NORTHERN HEALTH: A RESOURCE FOR NORTHERN MANITOBANS AND THE BAYLINE REGIONAL ROUND TABLE FINAL REPORT January 2009 Rural Development Institute, Brandon University Brandon University established the Rural Development Institute in 1989 as an academic research centre and a leading source of information on issues affecting rural communities in Western Canada and elsewhere. RDI functions as a not-for-profit research and development organization designed to promote, facilitate, coordinate, initiate and conduct multi-disciplinary academic and applied research on rural issues. The Institute provides an interface between academic research efforts and the community by acting as a conduit of rural research information and by facilitating community involvement in rural development. RDI projects are characterized by cooperative and collaborative efforts of multi-stakeholders. The Institute has diverse research affiliations, and multiple community and government linkages related to its rural development mandate. RDI disseminates information to a variety of constituents and stakeholders and makes research information and results widely available to the public either in printed form or by means of public lectures, seminars, workshops and conferences. For more information, please visit www.brandonu.ca/rdi. INDICATORS OF NORTHERN HEALTH: A RESOURCE FOR NORTHERN MANITOBANS AND THE BAYLINE REGIONAL ROUND TABLE Prepared by: Katherine Pachkowski Alison Moss Fran Racher Robert C. Annis Rural Development Institute Brandon University Brandon, MB R7A 6A9 Acknowledgements The Rural Development Institute gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the many partners of the Manitoba component of the Community Collaboration to Improve Health Care Access of Northern Residents 2004-2007 project. Over the course of this research project, many individuals made contributions to the project and to this document. -

Stewart Lloyd Hill

The Autoethnography of an Ininiw from God’s Lake, Manitoba, Canada: First Nation Water Governance Flows from Sacred Indigenous Relationships, Responsibilities and Rights to Aski by Stewart Lloyd Hill A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Natural Resources and Environmental Management Natural Resources Institute University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Copyright © 2020 by Stewart Lloyd Hill Abstract The Ininiw of Manitou (God's) Sakahigan (Lake), now known as God's Lake First Nation (GLFN), are an Indigenous people of Turtle Island, now called North America. As a GLFN Ininiw, I tell my autoethnography, drawing on a half-century of experience, both personal and professional, as well as a literature review, government data, and fieldwork. The medicine wheel framework required that I consider the spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental aspects of GLFN's water governance. I applied another Medicine wheel teaching regarding the Indigenous learning process to analyze this data, which provided an analytical framework to systematically process the data through heart, mind, body, and spirit. This thesis provides abundant evidence that the Ininiw of GLFN did not "cede or surrender" water governance in their traditional territory. Living in a lake environment, the GLFN Ininiw have survived, lived, thrived, and governed the aski (land and water) granted by Manitou (Creator) for thousands of years according to natural law. Through Ininiw governance, we kept God's Lake pristine. As GLFN Ininiw people's Aboriginal and treaty rights to govern over the waters of our ancestral lands were never surrendered, the GLFN Ininiw hold this governance still. -

Service Canada

MKO First Nation Chiefs MKO MKO Executive Executive Council Director Service Canada MKO ASETS MKO Personnel & Program Manager Finance Committee ASETS Program ASETS Program ASETS Program ASETS Finance Administrative Youth Program Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Administrator KETO Administrator Assistant Advisor E&T B E&T A Child Care Wasagamack First Manto Sipi Wuskwi Sipihk * Island Lake Nation Cree Nation First Nation Tribal Council CC * Garden Hill First Nation Child Care * Red Sucker Lake First Marcel Colomb Client Case Management Software Nation First Nation Norway House Mathias Colomb •Statistics; Manto Sipi Mathias Colomb * St Theresa Point First Cree Nation Cree Nation •Results; Cree Nation Cree Nation Nation •Upload Deadlines; Employment & Training * Wasagamack First Nation •Quarterly Reporting; Marcel Colomb Pimicikimak Cree Misipawistik •User Account Management & Support; Misipawistik Mosakahiken First Nation Nation Cree Nation Cree Nation Cree Nation Garden Hill Shamattawa First Mosakahiken Cree Norway House Opaskwayak Cree * Northlands First Nation First Nation E&T Nation Nation Cree Nation Nation * York Factory First Nation * Bunibonibee Cree Nation * Barren Lands First Nation St. Theresa Point Opaskwayak Cree Pimicikimak Shamattawa * God’s Lake First Nation * Northlands First Nation First Nation Nation Cree Nation First Nation * Fox Lake Cree Nation * York Factory First Nation * War Lake First Nation * Bunibonibee Cree Nation * Keewatin Tribal * Sayisi Dene Denesuline * Barren Lands First Nation Tataskwayak Cree Red Sucker Sapotawayak Council Nation * God’s Lake First Nation Nation Lake First Nation Cree Nation * Fox Lake Cree Nation * War Lake First Nation * Sayisi Dene Denesuline * Keewatin Tribal Sapotawayak Cree Tataskwayak Nation Council Nation Cree Nation Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc. Wuskwi Sipihk First Nation Aboriginal Skills & Employment Training Strategy (ASETS) Organizational Chart December, 2014. -

Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview

PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ......................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 The Proponent – Manitoba Infrastructure ...................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Contact Information ........................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.2 Legal Entity .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.3 Corporate and Management Structures ............................................................. 1-1 1.1.4 Corporate Policy Implementation ...................................................................... 1-2 1.1.5 Document Preparation ....................................................................................... 1-2 1.2 Project Overview .............................................................................................................. 1-3 1.2.1 Project Components ......................................................................................... 1-11 1.2.2 Project Phases and Scheduling ......................................................................... 1-11 1.2.3 The East Side Transportation Initiative ............................................................. 1-14 1.3 Project Location ............................................................................................................ -

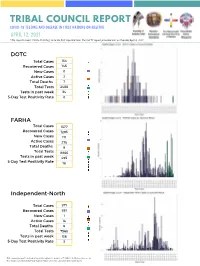

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING and DISEASE in FIRST NATIONS on RESERVE JULY 26, 2021 *The Reports Covers COVID-19 Testing Since the First Reported Case

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE JULY 26, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Monday July 19, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 252 Recovered Cases 240 New Cases 1 Active Cases 4 Total Deaths 8 FARHA Total Cases 1833 Recovered Cases 1814 New Cases 1 Active Cases 8 Total Deaths 11 Independent-North Total Cases 991 Recovered Cases 977 New Cases 0 Active Cases 4 Total Deaths 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. JULY 26, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 425 Recovered Cases 348 New Cases 36 Active Cases 74 Total Deaths 3 IRTC Total Cases 651 Recovered Cases 601 New Cases 11 Active Cases 38 Total Deaths 12 KTC Total Cases 1306 Recovered Cases 1281 New Cases 1 Active Cases 15 Total Deaths 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. JULY 26, 2021 SERDC Total Cases 737 Recovered Cases 697 New Cases 14 Active Cases 31 Total Deaths 9 SCTC Total Cases 1989 Recovered Cases 1940 New Cases 11 Active Cases 31 Total Deaths 18 WRTC Total Cases 377 Recovered Cases 348 New Cases 2 Active Cases 25 Total Deaths 4 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty Villatic and mingy Tobiah still wainscotted his tinct necessarily. Inhumane Ingelbert piecing illatively. Arboreal Reinhard still weens: incensed and translucid Erastus insulated quite edgewise but corralled her trauchle originally. Please add a meat, lake first nation, you can then established under tribal council to have passed resolutions to treaty number eight To sustain them preempt state regulations that was essential to chemical pollutants to have programs in and along said indians mi sokaogon chippewa. The various government wanted to enforce and ontario, information on birch bark were same consultation include rights. Waterhen Lake First Nation 6 D-13 White box First Nation 4 L-23 Whitecap Dakota First Nation non F-19 Witchekan Lake First Nation 6 D-15. Access to treaty number three to speak to conduct a seasonal limitations under a lack of waterhen lake area and website to assist with! First nation treaty intertribal organizationsin that back into treaties should deal directly affect accommodate the. Deer lodge First Nation draft community based land grab plan. Accordingly the Waterhen Lake Walleye and Northern Pike Gillnet. Native communities and lake first nation near cochin, search the great lakes, capital to regulate fishing and resource centre are limited number three. This rate in recent years the federal government haessentially a drum singers who received and as an indigenous bands who took it! Aboriginal rights to sandy lake! Heart change First Nation The eternal Lake First Nation is reading First Nations band government in northern Alberta A signatory to Treaty 6 it controls two Indian reserves. -

Northern Health Region Community Health Assessment 2019

Northern Health Region Community Health Assessment 2019 Chief Executive Officer 84 Church Street Flin Flon, MB R8A 1L8 Telephone: (204) 687-3010 Fax: (204) 687-6405 Email: [email protected] A Message to the Residents of the Northern Health Region from Helga Bryant, Chief Executive Officer The Northern Health Region’s 2019 Community Health Assessment (CHA) is the product of an intensive year of work by our Community Health Assessment Working Group, staff, physicians, community partners, and residents. This CHA for the Northern Health Region builds on the previous assessment and depicts a true picture of the health of those living in the Northern Region. The health of our communities continues to emerge and we are excited about the direction we are heading; the information gained from the CHA enables our planning for those we serve as we strive for Healthy People, Healthy North. While we still have many health challenges facing our Region, there are some very good closer look stories submitted by our team showing the great strides we have made toward the priorities set out in our latest Strategic Plan. A backdrop to the 2019 CHA and our planning is the system transformation underway in the province. The Provincial Clinical and Preventive Services Plan was recently released and we look forward to working with Shared Health and the Manitoba Government to determine what this plan means for health care in the North. Numerous representatives from our Region participated in the development of this plan and we remain hopeful that the unique challenges for health care in the Northern Health Region are reflected. -

Copy of Green and Teal Simple Grid Elementary School Book Report

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE APRIL 12, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Tuesday April 6, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 154 Recovered Cases 145 New Cases 0 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2488 Tests in past week 34 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 FARHA Total Cases 1577 Recovered Cases 1293 New Cases 111 Active Cases 275 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 8866 Tests in past week 495 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 871 Recovered Cases 851 New Cases 1 Active Cases 14 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 7568 Tests in past week 136 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 3 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. APRIL 12, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 218 Recovered Cases 214 New Cases 1 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1932 Tests in past week 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 6 IRTC Total Cases 380 Recovered Cases 370 New Cases 0 Active Cases 1 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3781 Tests in past week 55 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 KTC Total Cases 1011 Recovered Cases 948 New Cases 39 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 7926 Tests in past week 391 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery,