Applying Density and Hotspot Analysis for Indigenous Traditional Land Use: Counter-Mapping with Wasagamack First Nation, Manitoba, Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous-Led, Land-Based Programming Facilitating Connection to the Land and Within the Community

Indigenous-Led, Land-Based Programming Facilitating Connection to the Land and within the Community By Danielle R. Cherpako Social Connectedness Fellow 2019 Samuel Centre for Social Connectedness www.socialconnectedness.org August 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary Section 1: Introduction --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 1.1 Research and outreach methodology Section 2: Misipawistik Cree Nation: History & Disruptions to the Land ----------------------------- 5 2.1 Misipawistik Cree Nation 2.2 Settler-colonialism as a disruption to the connection to the land 2.3 The Grand Rapids Generating Station construction and damage to the land 2.4 The settlement of Hydro workers and significant social problems 2.5 The climate crisis as a disruption to the connection to the land 2.6 Testimonies from two local Elders, Alice Cook and Melinda Robinson Section 3: Reconnecting to the Land using Land-Based Programming ------------------------------ 16 3.1 Misipawistik Pimatisiméskanaw land-based learning program 3.1 (a) Providing culturally relevant education and improving retention of students, 3.1 (b) Revitalizing Cree culture, discovering identity and reconnecting to the land, 3.1 (c) Addressing the climate crisis and creating stewards of the land, 3.1 (d) Building community connectedness (Including input from Elders and youth). 3.2 Misipawistik’s kanawenihcikew Guardians program Section 4: Land-Based Programming in Urban School Divisions -------------------------------------- 25 4.1 -

Indicators of Northern Health: a Resource for Northern Manitobans and the Bayline Regional Round Table

INDICATORS OF NORTHERN HEALTH: A RESOURCE FOR NORTHERN MANITOBANS AND THE BAYLINE REGIONAL ROUND TABLE FINAL REPORT January 2009 Rural Development Institute, Brandon University Brandon University established the Rural Development Institute in 1989 as an academic research centre and a leading source of information on issues affecting rural communities in Western Canada and elsewhere. RDI functions as a not-for-profit research and development organization designed to promote, facilitate, coordinate, initiate and conduct multi-disciplinary academic and applied research on rural issues. The Institute provides an interface between academic research efforts and the community by acting as a conduit of rural research information and by facilitating community involvement in rural development. RDI projects are characterized by cooperative and collaborative efforts of multi-stakeholders. The Institute has diverse research affiliations, and multiple community and government linkages related to its rural development mandate. RDI disseminates information to a variety of constituents and stakeholders and makes research information and results widely available to the public either in printed form or by means of public lectures, seminars, workshops and conferences. For more information, please visit www.brandonu.ca/rdi. INDICATORS OF NORTHERN HEALTH: A RESOURCE FOR NORTHERN MANITOBANS AND THE BAYLINE REGIONAL ROUND TABLE Prepared by: Katherine Pachkowski Alison Moss Fran Racher Robert C. Annis Rural Development Institute Brandon University Brandon, MB R7A 6A9 Acknowledgements The Rural Development Institute gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the many partners of the Manitoba component of the Community Collaboration to Improve Health Care Access of Northern Residents 2004-2007 project. Over the course of this research project, many individuals made contributions to the project and to this document. -

Stewart Lloyd Hill

The Autoethnography of an Ininiw from God’s Lake, Manitoba, Canada: First Nation Water Governance Flows from Sacred Indigenous Relationships, Responsibilities and Rights to Aski by Stewart Lloyd Hill A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Natural Resources and Environmental Management Natural Resources Institute University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Copyright © 2020 by Stewart Lloyd Hill Abstract The Ininiw of Manitou (God's) Sakahigan (Lake), now known as God's Lake First Nation (GLFN), are an Indigenous people of Turtle Island, now called North America. As a GLFN Ininiw, I tell my autoethnography, drawing on a half-century of experience, both personal and professional, as well as a literature review, government data, and fieldwork. The medicine wheel framework required that I consider the spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental aspects of GLFN's water governance. I applied another Medicine wheel teaching regarding the Indigenous learning process to analyze this data, which provided an analytical framework to systematically process the data through heart, mind, body, and spirit. This thesis provides abundant evidence that the Ininiw of GLFN did not "cede or surrender" water governance in their traditional territory. Living in a lake environment, the GLFN Ininiw have survived, lived, thrived, and governed the aski (land and water) granted by Manitou (Creator) for thousands of years according to natural law. Through Ininiw governance, we kept God's Lake pristine. As GLFN Ininiw people's Aboriginal and treaty rights to govern over the waters of our ancestral lands were never surrendered, the GLFN Ininiw hold this governance still. -

Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview

PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview PROJECT 6 – ALL-SEASON ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ......................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 The Proponent – Manitoba Infrastructure ...................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Contact Information ........................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.2 Legal Entity .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.3 Corporate and Management Structures ............................................................. 1-1 1.1.4 Corporate Policy Implementation ...................................................................... 1-2 1.1.5 Document Preparation ....................................................................................... 1-2 1.2 Project Overview .............................................................................................................. 1-3 1.2.1 Project Components ......................................................................................... 1-11 1.2.2 Project Phases and Scheduling ......................................................................... 1-11 1.2.3 The East Side Transportation Initiative ............................................................. 1-14 1.3 Project Location ............................................................................................................ -

Treaty 5 Treaty 2

Bennett Wasahowakow Lake Cantin Lake Lake Sucker Makwa Lake Lake ! Okeskimunisew . Lake Cantin Lake Bélanger R Bélanger River Ragged Basin Lake Ontario Lake Winnipeg Nanowin River Study Area Legend Hudwin Language Divisi ons Cobham R Lake Cree Mukutawa R. Ojibway Manitoba Ojibway-Cree .! Chachasee R Lake Big Black River Manitoba Brandon Winnipeg Dryden !. !. Kenora !. Lily Pad !.Lake Gorman Lake Mukutawa R. .! Poplar River 16 Wakus .! North Poplar River Lake Mukwa Narrowa Negginan.! .! Slemon Poplarville Lake Poplar Point Poplar River Elliot Lake Marchand Marchand Crk Wendigo Point Poplar River Poplar River Gilchrist Palsen River Lake Lake Many Bays Lake Big Stone Point !. Weaver Lake Charron Opekamank McPhail Crk. Lake Poplar River Bull Lake Wrong Lake Harrop Lake M a n i t o b a Mosey Point M a n i t o b a O n t a r i o O n t a r i o Shallow Leaf R iver Lewis Lake Leaf River South Leaf R Lake McKay Point Eardley Lake Poplar River Lake Winnipeg North Etomami R Morfee Berens River Lake Berens River P a u i n g a s s i Berens River 13 ! Carr-Harris . Lake Etomami R Treaty 5 Berens Berens R Island Pigeon Pawn Bay Serpent Lake Pigeon River 13A !. Lake Asinkaanumevatt Pigeon Point .! Kacheposit Horseshoe !. Berens R Kamaskawak Lake Pigeon R !. !. Pauingassi Commissioner Assineweetasataypawin Island First Nation .! Bradburn R. Catfish Point .! Ridley White Beaver R Berens River Catfish .! .! Lake Kettle Falls Fishing .! Lake Windigo Wadhope Flour Point Little Grand Lake Rapids Who opee .! Douglas Harb our Round Lake Lake Moar .! Lake Kanikopak Point Little Grand Pigeon River Little Grand Rapids 14 Bradbury R Dogskin River .! Jackhead R a p i d s Viking St. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

Northern Health Region Community Health Assessment 2019

Northern Health Region Community Health Assessment 2019 Chief Executive Officer 84 Church Street Flin Flon, MB R8A 1L8 Telephone: (204) 687-3010 Fax: (204) 687-6405 Email: [email protected] A Message to the Residents of the Northern Health Region from Helga Bryant, Chief Executive Officer The Northern Health Region’s 2019 Community Health Assessment (CHA) is the product of an intensive year of work by our Community Health Assessment Working Group, staff, physicians, community partners, and residents. This CHA for the Northern Health Region builds on the previous assessment and depicts a true picture of the health of those living in the Northern Region. The health of our communities continues to emerge and we are excited about the direction we are heading; the information gained from the CHA enables our planning for those we serve as we strive for Healthy People, Healthy North. While we still have many health challenges facing our Region, there are some very good closer look stories submitted by our team showing the great strides we have made toward the priorities set out in our latest Strategic Plan. A backdrop to the 2019 CHA and our planning is the system transformation underway in the province. The Provincial Clinical and Preventive Services Plan was recently released and we look forward to working with Shared Health and the Manitoba Government to determine what this plan means for health care in the North. Numerous representatives from our Region participated in the development of this plan and we remain hopeful that the unique challenges for health care in the Northern Health Region are reflected. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Education A COMPARATIVE SOCIO-HISTORICAL CONTENT ANALYSIS OF TREATIES AND CURRENT AMERICAN INDIAN EDUCATION LEGISLATION WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR THE STATE OF MICHIGAN A Thesis in Educational Leadership by Martin J. Reinhardt ©2004 Martin J. Reinhardt Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December, 2004 ii The thesis of Martin J. Reinhardt has been reviewed and approved by the following: John W. Tippeconnic III Professor of Education Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee William L. Boyd Batschelet Chair Professor of Education Susan C. Faircloth Assistant Professor of Education Edgar I. Farmer Professor of Education Nona A. Prestine Professor of Education In Charge of Graduate Programs in Educational Leadership *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT This study is focused on the relationship between two historical policy era of American Indian education--the Constitutional/Treaty Provisions Era and the Self- Determination/Revitalization Era. The primary purpose of this study is the clarification of what extent treaty educational obligations may be met by current federal K-12 American Indian education legislation. An historical overview of American Indian education policy is provided to inform the subsequent discussion of the results of a content analysis of sixteen treaties entered into between the United States and the Anishinaabe Three Fires Confederacy, and three pieces of federal Indian education legislation-the Indian Education Act (IEA), the Indian Self-Determination & Education Assistance Act (ISDEA), and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures …………………………………………………………………...... vii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………… ......... -

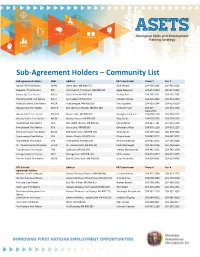

Sub-‐Agreement Holders – Community List

Sub-Agreement Holders – Community List Sub-Agreement Holders Abbr. Address E&T Coordinator Phone # Fax # Garden Hill First Nation GHFN Island Lake, MB R0B 0T0 Elsie Monias 204-456-2085 204-456-9315 Keewatin Tribal Council KTC 23 Nickel Rd, Thompson, MB R8N 0Y4 Aggie Weenusk 204-677-0399 204-677-0257 Manto Sipi Cree Nation MSCN God's River, MB R0B 0N0 Bradley Ross 204-366-2011 204-366-2282 Marcel Colomb First Nation MCFN Lynn Lake, MB R0B 0W0 Noreena Dumas 204-356-2439 204-356-2330 Mathias Colomb Cree Nation MCCN Pukatawagon, MB R0B 1G0 Flora Bighetty 204-533-2244 204-553-2029 Misipawistik Cree Nation MCN'G Box 500 Grand Rapids, MB R0C 1E0 Melina Ferland 204-639- 204-639-2503 2491/2535 Mosakahiken Cree Nation MCN'M Moose Lake, MB R0B 0Y0 Georgina Sanderson 204-678-2169 204-678-2210 Norway House Cree Nation NHCN Norway House, MB R0B 1B0 Tony Scribe 204-359-6296 204-359-6262 Opaskwayak Cree Nation OCN Box 10880 The Pas, MB R0B 2J0 Joshua Brown 204-627-7181 204-623-5316 Pimicikamak Cree Nation PCN Cross Lake, MB R0B 0J0 Christopher Ross 204-676-2218 204-676-2117 Red Sucker Lake First Nation RSLFN Red Sucker Lake, MB R0B 1H0 Hilda Harper 204-469-5042 204-469-5966 Sapotaweyak Cree Nation SCN Pelican Rapids, MB R0B 1L0 Clayton Audy 204-587-2012 204-587-2072 Shamattawa First Nation SFN Shamattawa, MB R0B 1K0 Jemima Anderson 204-565-2041 204-565-2606 St. Theresa Point First Nation STPFN St. Theresa Point, MB R0B 1J0 Curtis McDougall 204-462-2106 204-462-2646 Tataskweyak Cree Nation TCN Split Lake, MB R0B 1P0 Yvonne Wastasecoot 204-342-2951 204-342-2664