Fundamentals of RF Propagation in Electronic Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art and Science of Forecasting Morning Temperature Inversions by Anthony J

Air Quality Forecasting Excl usive Con tent The Art and Science of Forecasting Morning Temperature Inversions by Anthony J. Sadar Anthony J. Sadar is a Certified Consulting Meteorologist and Air Pollution Administrator with the Allegheny County Health Department, Air Quality Program in Pittsburgh, PA. E-mail: [email protected]. The author provides an overview of the key resources and variables used to produce morning surface air inversion forecasts in Pittsburgh, PA. Although the focus is southwestern Pennsylvania, the forecasting approach can be applied to similar locations across the globe. Air quality in southwestern Pennsylvania, as in most other areas of the Accurate forecasting of the onset of an inversion would benefit areas world, is very much influenced by surface-based temperature inver - prone to strong and/or persistent inversions. Advanced notice of im - sions. An atmospheric temperature inversion occurs when air temper - pending stagnant air conditions would give government regulators, ature increases with increasing height. In the layer of air nearest the industry operators, and the public time to mitigate emissions, and earth’s surface—the troposphere—this situation is the inverse of the hence, pollutant concentrations, as well as reduce exposure to “normal” condition where a warm ground keeps low-lying air warmer elevated pollution levels. than air higher up. Normally then, the warm surface air can rise and the cool air aloft can descend, causing the atmosphere to mix. Detecting Inversions To collect temperature, wind, and other data with height, the National A surface-based (or ground-level) temperature inversion forms Weather Service (NWS) releases a balloon-borne measurement trans - when air close to the ground cools faster than air at a higher altitude. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Anticyclones

Anticyclones Background Information for Teachers “High and Dry” A high pressure system, also known as an anticyclone, occurs when the weather is dominated by stable conditions. Under an anticyclone air is descending, maybe linked to the large scale pattern of ascent and descent associated with the Global Atmospheric Circulation, or because of a more localized pattern of ascent and descent. As shown in the diagram below, when air is sinking, more air is drawn in at the top of the troposphere to take its place and the sinking air diverges at the surface. The diverging air is slowed down by friction, but the air converging at the top isn’t – so the total amount of air in the area increases and the pressure rises. More for Teachers – Anticyclones Sinking air gets warmer as it sinks, the rate of evaporation increases and cloud formation is inhibited, so the weather is usually clear with only small amounts of cloud cover. In winter the clear, settled conditions and light winds associated with anticyclones can lead to frost. The clear skies allow heat to be lost from the surface of the Earth by radiation, allowing temperatures to fall steadily overnight, leading to air or ground frosts. In 2013, persistent High pressure led to cold temperatures which caused particular problems for hill sheep farmers, with sheep lambing into snow. In summer the clear settled conditions associated with anticyclones can bring long sunny days and warm temperatures. The weather is normally dry, although occasionally, localized patches of very hot ground temperatures can trigger thunderstorms. An anticyclone situated over the UK or near continent usually brings warm, fine weather. -

Synoptic Meteorology

Lecture Notes on Synoptic Meteorology For Integrated Meteorological Training Course By Dr. Prakash Khare Scientist E India Meteorological Department Meteorological Training Institute Pashan,Pune-8 186 IMTC SYLLABUS OF SYNOPTIC METEOROLOGY (FOR DIRECT RECRUITED S.A’S OF IMD) Theory (25 Periods) ❖ Scales of weather systems; Network of Observatories; Surface, upper air; special observations (satellite, radar, aircraft etc.); analysis of fields of meteorological elements on synoptic charts; Vertical time / cross sections and their analysis. ❖ Wind and pressure analysis: Isobars on level surface and contours on constant pressure surface. Isotherms, thickness field; examples of geostrophic, gradient and thermal winds: slope of pressure system, streamline and Isotachs analysis. ❖ Western disturbance and its structure and associated weather, Waves in mid-latitude westerlies. ❖ Thunderstorm and severe local storm, synoptic conditions favourable for thunderstorm, concepts of triggering mechanism, conditional instability; Norwesters, dust storm, hail storm. Squall, tornado, microburst/cloudburst, landslide. ❖ Indian summer monsoon; S.W. Monsoon onset: semi permanent systems, Active and break monsoon, Monsoon depressions: MTC; Offshore troughs/vortices. Influence of extra tropical troughs and typhoons in northwest Pacific; withdrawal of S.W. Monsoon, Northeast monsoon, ❖ Tropical Cyclone: Life cycle, vertical and horizontal structure of TC, Its movement and intensification. Weather associated with TC. Easterly wave and its structure and associated weather. ❖ Jet Streams – WMO definition of Jet stream, different jet streams around the globe, Jet streams and weather ❖ Meso-scale meteorology, sea and land breezes, mountain/valley winds, mountain wave. ❖ Short range weather forecasting (Elementary ideas only); persistence, climatology and steering methods, movement and development of synoptic scale systems; Analogue techniques- prediction of individual weather elements, visibility, surface and upper level winds, convective phenomena. -

Thermal Inversion and Particulate Matter Concentration in Wrocław in Winter Season

atmosphere Article Thermal Inversion and Particulate Matter Concentration in Wrocław in Winter Season Jadwiga Nidzgorska-Lencewicz * and Małgorzata Czarnecka Department of Environmental Management, West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin, ul. Papie˙zaPawła VI, 71-459 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 7 December 2020; Published: 12 December 2020 Abstract: Studies on air quality frequently adopt clustering, in particular the k-means technique, owing to its simplicity, ease of implementation and efficiency. The aim of the present paper was the assessment of air quality in a winter season (December–February) in the conditions of temperature inversion using the k-means method, representing a non-hierarchical algorithm of cluster analysis. The air quality was assessed on the basis of the concentrations of particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5). The studies were conducted in four winter seasons (2015/16, 2016/17, 2017/18, 2019/20) in Wrocław (Poland). As a result of the application of the v-fold cross test, six clusters for each fraction of PM were identified. Even though the analysis covers only four winter seasons, the applied method has unequivocally revealed that the characteristics of surface-based (SBI) and elevated inversions (ELI) affect the concentration level of both fractions of particulate matter. In the case of PM10, the average lowest daily concentration (15.5 µg m 3) was recorded in the conditions of approx. 205 m in thickness, · − 0.5 ◦C intensity of the SBI and at the height of the base of the ELI at approx. 1700 m a.g.l., a thickness of 148 m and an intensity of 1.2 C. -

Temperature Inversions.Pdf

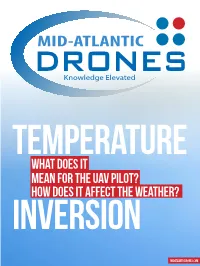

MID-ATLANTIC dronesKnowledge Elevated TEMPERATURE WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR THE UAV PILOT? HOW DOES IT AFFECT THE WEATHER? INVERSION midatlanticdrones.com #TEMPERATUREINVERSION Temperature inversion: a layer of cool air at the surface is overlain by a layer of warmer air NORMAL CONDITIONS TEMPERATURE INVERSION COLD AIR COLD AIR COLD AIR COLD AIR WARMER AIR WARMER AIR COOLER AIR COOLER AIR WARMER AIR WARMER AIR COOLER AIR COOLER AIR On the left, arrows show normal conditions: Warm air rises and normal convective patterns persist. During temperature inversion, shown on the right, the warm air acts like a cap, shutting down convection and trapping smog over the city. #TEMPERATUREINVERSION warm air on top of cold air Expect fog and haze temp/dew point spread is low little convection – A temperature inversion means some warm air on top of some cold air. – The cold air underneath on the ground, along with a high relative humidity, means you are expecting fog in the cooler area. – If you check the METARS for the airports in the area as you will most likely have a temperature/dewpoint spread that is low. – The air will be smooth because there is little convection. #TEMPERATUREINVERSION 3 what does this mean for you, the drone pilot? Temperature inversions can represent an important element of air pollution, especially in places that are inhabitted, and in valleys. The warmer air layer acts as a natural lid that keeps pollution and dirt trapped. This trapped layer of dirty air stays in there unable to escape. The main issue for UAVs is visibility. -

Effects of Anomalous Propagation Conditions on Weather Radar Observations

13 Effects of Anomalous Propagation Conditions on Weather Radar Observations Joan Bech1, Adolfo Magaldi2, Bernat Codina1 and Jeroni Lorente1 1Dep. Astronomy and Meteorology, University of Barcelona 2Institute of Space Sciences, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Bellatera Spain 1. Introduction The effect of atmospheric propagation on radar observations is an important topic both for radar application developers and end-users of radar products, particularly of weather radar systems. An excellent review of this subject is given by Patterson (2008), and most general books about weather radars have a chapter on the topic –see for example Battan (1973), Collier (1996), Doviak and Zrnic (2006), Rinehart (2001) or Sauvageot (1991). In this chapter our objective is to provide an overview of the effects of anomalous propagation conditions on weather radar observations, based mostly on studies performed by the authors during the last decade, summarizing results from recent publications, presentations, or unpublished material. We believe this chapter may be useful as an introductory text for graduate students, or researchers and practitioners dealing with this topic. Throughout the text a spherical symmetric atmosphere is assumed and the focus is on the occurrence of ground and sea clutter and subsequent problems for weather radar applications. Other related topics such as long-path, over-the-horizon propagation and detection of radar targets (either clutter or weather systems) at long ranges is not considered here; however readers should be aware of the potential problems these phenomena may have as range aliasing may cause these echoes appear nearer than they are – for more details see the discussion about second trip echoes by Zrnic, this volume. -

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms -A- Anvil The flat, spreading top of a cloud, often shaped like an anvil. Thunderstorm anvils may spread hundreds of miles downwind from the thunderstorm itself, and sometimes may spread upwind. Anvil Dome A large overshooting top or penetrating top. -B- Back-building Thunderstorm A thunderstorm in which new development takes place on the upwind side (usually the west or southwest side), such that the storm seems to remain stationary or propagate in a backward direction. Back-sheared Anvil [Slang], a thunderstorm anvil which spreads upwind, against the flow aloft. A back-sheared anvil often implies a very strong updraft and a high severe weather potential. Beaver ('s) Tail [Slang], a particular type of inflow band with a relatively broad, flat appearance suggestive of a beaver's tail. It is attached to a supercell's general updraft and is oriented roughly parallel to the pseudo-warm front, i.e., usually east to west or southeast to northwest. As with any inflow band, cloud elements move toward the updraft, i.e., toward the west or northwest. Its size and shape change as the strength of the inflow changes. Spotters should note the distinction between a beaver tail and a tail cloud. A "true" tail cloud typically is attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same level as the wall cloud itself. A beaver tail, on the other hand, is not attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same height as the updraft base (which by definition is higher than the wall cloud). -

Elevated Cold-Sector Severe Thunderstorms: a Preliminary Study

ELEVATED COLD-SECTOR SEVERE THUNDERSTORMS: A PRELIMINARY STUDY Bradford N. Grant* National Weather Service National Severe Storms Forecast Center Kansas City, Missouri Abstract sector. However, these elevated storms can still produce a sig A preliminary study of atmospheric conditions in the vicinity nificant amount of severe weather and are more numerous than of severe thunderstorms that occurred in the cold sector, north one might expect. of east-west frontal boundaries, is presented. Upper-air sound Colman (1990) found that nearly all cool season (Nov-Feb) ings, suiface data and PCGRIDDS data were collected and thunderstorms east of the Rockies, with the exception of those analyzed from a total of eleven cases from April 1992 through over Florida, were of the elevated type. The environment that April 1994. The selection criteria necessitated that a report produced these thunderstorms displayed significantly different occur at least fifty statute miles north of a well-defined frontal thermodynamic characteristics from environments whose thun boundary. A brief climatology showed that the vast majority derstorms were rooted in the boundary layer. In addition, he of reports noted large hail (diameter: 1.00-1.75 in.) and that found a bimodal variation in the seasonal distribution of ele the first report of severe thunderstorms occurred on an average vated thunderstorms with a primary maximum in April and a of 150 miles north of the frontal boundary. Data from 22 secondary maximum in September. The location of the primary proximity soundings from these cases revealed a strong baro maximum of occurrence in April was over the lower Mississippi clinic environment with strong vertical wind shear and warm Valley. -

PHAK Chapter 12 Weather Theory

Chapter 12 Weather Theory Introduction Weather is an important factor that influences aircraft performance and flying safety. It is the state of the atmosphere at a given time and place with respect to variables, such as temperature (heat or cold), moisture (wetness or dryness), wind velocity (calm or storm), visibility (clearness or cloudiness), and barometric pressure (high or low). The term “weather” can also apply to adverse or destructive atmospheric conditions, such as high winds. This chapter explains basic weather theory and offers pilots background knowledge of weather principles. It is designed to help them gain a good understanding of how weather affects daily flying activities. Understanding the theories behind weather helps a pilot make sound weather decisions based on the reports and forecasts obtained from a Flight Service Station (FSS) weather specialist and other aviation weather services. Be it a local flight or a long cross-country flight, decisions based on weather can dramatically affect the safety of the flight. 12-1 Atmosphere The atmosphere is a blanket of air made up of a mixture of 1% gases that surrounds the Earth and reaches almost 350 miles from the surface of the Earth. This mixture is in constant motion. If the atmosphere were visible, it might look like 2211%% an ocean with swirls and eddies, rising and falling air, and Oxygen waves that travel for great distances. Life on Earth is supported by the atmosphere, solar energy, 77 and the planet’s magnetic fields. The atmosphere absorbs 88%% energy from the sun, recycles water and other chemicals, and Nitrogen works with the electrical and magnetic forces to provide a moderate climate. -

A Bayesian Methodology for Detecting Anomalous Propagation in Radar Reflectivity Observations

The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research A partnership between the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO A Bayesian methodology for detecting anomalous propagation in radar reflectivity observations Justin R. Peter, Alan Seed, Peter Steinle, Susan Rennie and Mark Curtis CAWCR Technical Report No. 077 December 2014 A Bayesian methodology for detecting anomalous propagation in radar reflectivity observations Justin R. Peter, Alan Seed, Peter Steinle, Susan Rennie and Mark Curtis. The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research – a partnership between CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology CAWCR Technical Report No. 077 December 2014 ISSN: 1835-9884 Authors: Peter, J.R., Seed, A., Steinle, P., Rennie, S. and Curtis, M. Title: A Bayesian methodology for detecting anomalous propagation in radar reflectivity observations. ISBN: 978-1-4863-0473-8 (Electronic Resource PDF) Series: CAWCR technical report. Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Contact details Enquiries should be addressed to: Dr Justin R. Peter Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research GPO Box 1289K Melbourne Vic 3001 Australia [email protected] Phone: +61 3 9669 4838 Copyright and disclaimer © 2014 CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology. CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. -

Trade Wind Inversion

Trade Wind Inversion Introduction The trade wind inversion is one of the most prominent manifestations of temperature inversions within the troposphere. Trade wind inversions are commonly found in association with the subtropical anticyclones connected to the descending branch of the time-averaged Hadley cell circulation. The trade wind inversion has impacts upon the sensible weather of the boundary layer across the subtropics and northern reaches of the tropics, particularly manifest in stability, cloud cover, and precipitation. In the following, we first describe the basic characteristics of the trade wind inversion and its impacts upon sensible weather in the tropics and subtropics. In so doing, we focus specifically upon its structure and impacts in the eastern North Pacific Ocean during Northern Hemisphere summer, although this can easily be generalized to any of the other ocean basins (e.g., eastern South Pacific Ocean, eastern North and South Atlantic Ocean, etc.) in which a trade wind inversion is present. We then develop lapse rate tendency equations to help us understand the factors influencing trade wind inversion formation and intensity. Key Concepts • What are the climatological structure and intensity of subtropical anticyclones? • How and why do vertical profiles of temperature and moisture vary with increasing distance from the center of a subtropical ridge? • What physical processes contribute to inversion formation and intensity? Trade Wind Inversion Structure and Impacts Trade wind inversions are commonly found in the eastern regions of the subtropical oceans and the western coastal regions of adjacent continents. The trade wind inversion is characterized by a layer in which temperature increases with increasing height above the surface layer, in which temperature decreases with increasing height.