Berengario's Drill: Origin and Inspiration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Headlok® and Spiderdrive® Are Registered Trademarks of OMG, Inc

® HeadLok PRODUCT DATA SPECIFICATIONS PRODUCT DESCRIPTION COATING The OMG HeadLok is a specialized, flat head OMG CR-10 corrosion resistant coating fastener engineered for a wide range of passes the corrosion requirements of FM panel applications including Structural Insu- Approval Standard 4470 and ETAG 006. lated Panels, Prefabricated Wall Panels, and APPLICATION USE Nailboard, and can also be used in wood, WITH structural concrete*, purlins*, corrugated Install the OMG HeadLok using a high torque, and structural steel substrates. low RPM screw gun. Bring underside of P the washer head flat to the surface. Do not FEATURES & BENEFITS overdrive. For steel substrates, proper point S • Three point and thread styles available style must be determined depending on the for fast installation. steel gauge thickness. W • Spade Point for use in in steel *For structural concrete, use the OMG SC HeadLok with spade points only. The fastener (18 - 22 ga.), structural concrete and DECK wood; must penetrate structural concrete decks a TYPES • Gimlet Point for use in dimensional minimum of 1-inch. Pre-drill using a 3/16-in. lumber; pilot hole at least 1/2-in. (13 mm) deeper than fastener embedment. • Drill Point for use in steel purlins PHYSICAL DATA** up to 3/16-in. thick. The 1/2-in. *For purlin attachment, use OMG HeadLok The data below is constant for each OMG HeadLok. with drill point only. drill point allows the fastener to be HEAD POINT STYLES SHANK drilled through the purlin before the *Prior to job-start, contact OMG to perform a .625" (15.87 mm) • Gimlet .190" (4.82 mm) threads engage. -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

Powers-Tapper.Pdf

NEW CONCRETE SCREW TECHNOLOGY Tapper ®+ INSTALLATION PROCEDURES Using the proper diameter bit, drill a hole into the base material to a depth of at least 1/2” deeper than the embedment The required. A TAPPER+ drill bit Tapper+ is a must be used. Blow the hole clean of dust and other material. one-piece self-tapping concrete screw for use in a Select the TAPPER+ installation tool and drive socket to be used. variety of light to medium duty Insert the head of the TAPPER+ into the hex head socket or applications in base materials including Phillips head driver. Set the drill concrete, masonry and wood. It features motor to the “rotation only” a corrosion resistant Perma-Seal ® coating mode to install. and an optimized thread design for lower Place the point of the TAPPER+ through the fixture into the pre- installation torque. The screw also incorporates drilled hole and drive the anchor a gimlet drill point for wood base materials in one steady continuous motion until it is fully seated at the (no pre-drilling required). Tapper+ is available proper embedment. The driver in a variety of head styles and colors to match will automatically disengage from the head of the TAPPER+. the application. Note: Do not select a length that will result in an embedment into the base material which is greater than 2". Most concrete screw anchors cannot be Top Performance of properly driven to a depth of more than 2", especially the Tapper ®+ Sets a in denser base materials. New Standard for Concrete Screws Powers TAPPER ®+ ITW TAPCON ® VS. -

Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256

NONRESIDENT TRAINING COURSE June 1992 Tools and Their Uses NAVEDTRA 14256 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Although the words “he,” “him,” and “his” are used sparingly in this course to enhance communication, they are not intended to be gender driven or to affront or discriminate against anyone. DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A : Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. NAVAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING PROGRAM MANAGEMENT SUPPORT ACTIVITY PENSACOLA, FLORIDA 32559-5000 ERRATA NO. 1 May 1993 Specific Instructions and Errata for Nonresident Training Course TOOLS AND THEIR USES 1. TO OBTAIN CREDIT FOR DELETED QUESTIONS, SHOW THIS ERRATA TO YOUR LOCAL-COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER). THE LOCAL COURSE ADMINISTRATOR (ESO/SCORER) IS DIRECTED TO CORRECT THE ANSWER KEY FOR THIS COURSE BY INDICATING THE QUESTIONS DELETED. 2. No attempt has been made to issue corrections for errors in typing, punctuation, etc., which will not affect your ability to answer the question. 3. Assignment Booklet Delete the following questions and write "Deleted" across all four of the boxes for that question: Question Question 2-7 5-43 2-54 5-46 PREFACE By enrolling in this self-study course, you have demonstrated a desire to improve yourself and the Navy. Remember, however, this self-study course is only one part of the total Navy training program. Practical experience, schools, selected reading, and your desire to succeed are also necessary to successfully round out a fully meaningful training program. THE COURSE: This self-study course is organized into subject matter areas, each containing learning objectives to help you determine what you should learn along with text and illustrations to help you understand the information. -

Woodworking in Estonia

WOODWORKING IN ESTONIA HISTORICAL SURVEY By Ants Viires Translated from Estonian by Mart Aru Published by Lost Art Press LLC in 2016 26 Greenbriar Ave., Fort Mitchell, KY 41017, USA Web: http://lostartpress.com Title: Woodworking in Estonia: Historical Survey Author: Ants Viires (1918-2015) Translator: Mart Aru Publisher: Christopher Schwarz Editor: Peter Follansbee Copy Editor: Megan Fitzpatrick Designer: Meghan Bates Index: Suzanne Ellison Distribution: John Hoffman Text and images are copyright © 2016 by Ants Viires (and his estate) ISBN: 978-0-9906230-9-0 First printing of this translated edition. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. This book was printed and bound in the United States. CONTENTS Introduction to the English Language Edition vii The Twisting Translation Tale ix Foreword to the Second Edition 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Literature, Materials & Methods 2 2. The Role Played by Woodwork in the Peasants’ Life 5 WOODWORK TECHNOLOGY 1. Timber 10 2. The Principal Tools 19 3. Processing Logs. Hollowing Work and Sealed Containers 81 4. Board Containers 96 5. Objects Made by Bending 127 6. Other Bending Work. Building Vehicles 148 7. The Production of Shingles and Other Small Objects 175 8. Turnery 186 9. Furniture Making and Other Carpentry Work 201 DIVISION OF LABOR IN THE VILLAGE 1. The Village Craftsman 215 2. Home Industry 234 FINAL CONCLUSIONS 283 Index 287 INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION feel like Captain Pike. -

SIP Fasteners for Structural Insulated Panel & Nail Base Construction

SIP Fasteners For Structural Insulated Panel & Nail Base Construction APPLICATION TRUFAST® SIP Fasteners are specifically engineered for attaching offers three fastener styles for use in wood, corrugated steel and steel structural insulated panels (SIPs) and nail base panels to wood and members without pre-drilling! Contact your panel manufacturer or metal framing. Featuring a large, pancake head style with a 6-lobe distributor to ask for a test drive of a TRUFAST SIP Fastener and see why drive, TRUFAST SIP Fasteners drive quickly and smoothly , and draw they’re the #1 fastener in the SIP industry. panels securely without the need of a washer. And only TRUFAST PRODUCT FEATURES • Case-hardened and tempered for easy installation and long-term durability • Large diameter, low profile pancake head provides excellent pull-through resistance without the need for a washer while eliminating “telegraphing” on shingles, metal panels, and other roof surface materials • 6-lobe internal drive offers excellent bit engagement during installation, especially in high torque applications • Widest selection of fastener lengths in the industry for proper sizing to panel thickness • Choice of 3 thread/point styles for job-matched performance in wood, steel, or concrete/CMU substrates CODE APPROVALS & LISTINGS FM Global Miami-Dade County DrJ Certification CE European Technical State of Florida Technical Evaluation Report Approval ETA 19/0616 FL# 4500-R4 TER 1909-04 MATERIAL SPECIFICATIONS Material: Case-hardened & tempered carbon steel Manufacturing Location: Bryan, OH USA Coating: TRU-KOTE™ Epoxy E-coat (black) LEED® Eligible Recycled Content: 20% SIPTP Thread Point for Wood, Timber, and Concrete/CMU Applications SIPLD Light-Duty Drill Point for Corrugated Steel Deck, Wood, & Concrete/CMU Applications SIPHD Heavy-Duty Drill Point for Thick Steel Member Applications ALTENLOH, BRINCK & CO. -

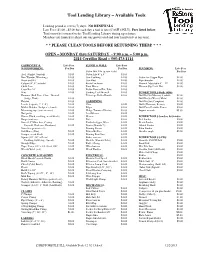

Tool Lending Library – Available Tools

Tool Lending Library – Available Tools Lending period is seven (7) days. NO RENEWALS Late Fees: $1.00 - $5.00 for each day a tool is late (CASH ONLY). Fees listed below . Tools must be returned to the Tool Lending Library during open hours. Members are limited to check out one power tool and four hand tools at one time. * * PLEASE CLEAN TOOLS BEFORE RETURNING THEM! * * * OPEN – MONDAY thru SATURDAY - 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 2414 Cerrillos Road – 505-473-1114 CARPENTRY & Late Fees FLOOR & WALL Late Fees WOODWORKING Per Day Per Day PLUMBING Late Fees Cutter Wet Tile (power tools) Per Day Awl, (Gimlet, Scratch) $1.00 Cutter Tile 4" x 6" $1.00 Bar (Wonder, Wrecking) $1.00 Gun Caulking $1.00 Cutter for Copper Pipe $1.00 Brace and Bit $1.00 Gun Heat $1.00 Pipe threader $1.00 Caliper (4", 6” outside) $1.00 Knife Linoleum $1.00 Wrench Adjustable 6” – 12” $1.00 Chalk Line $1.00 Paint Mixer $1.00 Wrench Slip Lock-Nut $1.00 Crow Bar 24" $1.00 Roller Paint w/Ext. Pole $1.00 Files $1.00 Sanding Tool Drywall $1.00 POWER TOOLS Drills &Bits Hammer (Ball Peen, Claw, Drywall, Telescope Roller Handle $1.00 Drill Bit Set Masonry Carbide $1.00 Sedge, Tack) $1.00 Drill Bit Set Wood / Metal $1.00 Hatchet $1.00 GARDENING Drill Bit Set (Complete) $1.00 Levels (torpedo, 2’ 3’ 4’) $1.00 Claw $1.00 Drills (Hammer, Rotary) $5.00 Mallet (Rubber, Sculptor’s, hand) $1.00 Edger $1.00 Drill Press Portable Power $5.00 Measuring tape (various sizes) $1.00 Hedge Trimmer Electric $3.00 Impact wrench $5.00 Nail puller $1.00 Leaf Blower $5.00 Planes (Hand, molding, wood block) -

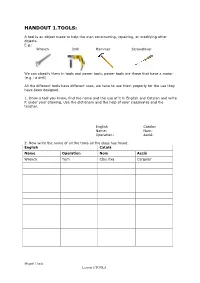

Handout 1.Tools

HANDOUT 1.TOOLS: A tool is an object made to help the man constructing, repairing, or modifying other objects. E.g.: Wrench Drill Hammer Screwdriver L We can classify them in tools and power tools, power tools are those that have a motor (e.g.: a drill) All the different tools have different uses, we have to use them properly for the use they have been designed. 1. Draw a tool you know, find the name and the use of it in English and Catalan and write it under your drawing. Use the dictionary and the help of your classmates and the teacher. English Catalan Name: Nom: Operation: Acció: 2. Now write the name of all the tools all the class has found: English Català Name Operation Nom Acció Wrench Turn Clau fixa Cargolar Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 2.TOOLS TABLE: Here’s a list of the most common tools in the workshop of the school: Rasp hacksaw Coping saw handsaw gimlet clamp C-clamp pliers Needle-nose pliers Round nose pliers Wire stripping pliers shears Hammer Ball-peen hammer Nilon mallet Riveting tool Rubber mallet Wrench (spanner) Flat head screwdriver Hot glue gun Torx screwdriver Flat Round file Bench vice file k Drill allen key Adjustable spanner Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 3. EMPTY TABLE: 3. Now hide the page you have been using before and in groups try to write all the names Miquel Llaràs Lesson 1-TOOLS HANDOUT 4.OPERATIONS: 1. These are different operations we can do with the tools in the workshop. -

General Workshop

CARPENTRY INTRODUCTION Wood is an important engineering material that is extensively used in the buildings and industries. ‘Timber’ is another name for wood, which is obtained from exogeneous trees. “Wood Working” means processing of wood by hand and machines for making articles of different shapes and sizes. It is further divided into two groups; (1) Carpentry (2) Pattern making. Carpentry is the common term used with any class of work with wood. Pattern making deals with the type and construction of wooden patterns. Steel Rule Four fold rule Flexible tape Blade Try square Stock List of Tools I. Marking and Measuring tools 1. Pencil 9. Combination square 2. Steel rule 10. Marking Knife (Scriber) 3. Four fold rule 11 Marking Gauge 4. Flexible tape 12 Mortise Gauge 5. Straight Edge 13. Wing compass 6. Try square 14. Trammel (beam compass) 7. Mitre Square 15 Calipers (Outside and Inside) 8. Bevel Square 16. Spirit level and plumb bob II. Cutting tools A. Saws B. Chisels C. Axes (a). Saws (b). Chisels 1. Hand Saw a. Firmer Chisel (Cross cut saw) 2. Rip Saw b. Bevel edged 3. Tenon saw (Back saw) c. Pairing Chisel 4. Panel Saw d. Mortise chisel 5. Dovetail Saw e. Gouges (Inside & outside) (c). Axes a. Side Axe b. Adze III. Planinng Tools a. Jack plane (wooden & Metal) b. Smoothing plane c. Rebate plane d. Spoke shave e. Trying plane f. Plough plane g. Router plane Bevel Square Marking knife Mortise gauge Marking gauge Marking pin IV. Boring Tools a. Gimlet b. Bradawl c. Brace (Ratchet & Wheel brace) d. -

Catalog 116 Power Drain Cleaner Comparison Chart

Catalog 116 Power Drain Cleaner Comparison Chart For Use in Maximum Typical Following Maximum Operating Recommended Motor Applications Pipe Sizes Capacity Weight Distance Horsepower Super-Vee 16 lbs. with Power-Vee 25 ft. x 3/8" Handylectric Sinks, 35 ft. x 3/8" or Pages 4 – 8 7 kg Bathtubs, 1-1/4" – 3" 50 ft. x 1/4” or 5/16" 50 ft. 3.2 amp 30 mm x 75 mm 10.5 m x 9.5 mm 15 m Drain-Rooter PH Roofstacks 34 lbs./15 kg Page 9 or 15 m x 7.9 mm DRZ 30 lbs./13 kg 1/5 hp Page 10 2" – 3" Small Drains, 62 lbs. Mini-Rooter Pro and most 4" 75 ft. x 1/2" or 3/8" 75 ft. Inside Work, With 75 ft. x 3/8" 1/3 hp Pages 12 – 13 30 mm – 100 mm 22.5 m x 12.7 mm 22.5 m On Roofs 28 kg (Not For Roots) 2" – 3" Small Drains, 92 lbs. Mini-Rooter XP and most 4" 75 ft. x 1/2" or 3/8" 75 ft. Inside Work, With 75 ft. x 3/8" 1/3 hp Pages 14 – 15 30 mm – 100 mm 22.5 m x 12.7 mm 22.5 m On Roofs 42 kg (Not For Roots) Small Drains, 2" – 3" Sewerooter T-3 Inside Work, 100 ft. x 1/2" 115 lbs. 100 ft. and most 4" 1/3 hp Pages 16 – 17 On Roofs 50 mm – 100 mm 30 m x 12.7 mm 52 kg 30 m (Not For Roots) 50 ft. -

21.4.2010 Who Was Benjamin Forstner

21.03 2010 Who was Benjamin Forstner? Do you know the history of the traditional Forstner Bit? Who invented this tool? Before introducing the winner of the Forstner drill test by American woodworkers most trusted magazine “Fine Woodworking”, we would like to present you Benjamin Forstner, the responsible for this fantastic invention. _______________________________________________________________________ Do you know the history of the traditional Forstner Bit? Who invented this tool? Before introducing the winner of the Forstner drill test by American woodworkers most trusted magazine “Fine Woodworking”, we would like to present you Benjamin Forstner, the responsible for this fantastic invention. THE HISTORY: Benjamin Forstner (25.03.1834 - † 27.02.1897) was born in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. He was an American gunsmith, inventor and a dry goods merchant. His ingenious invention of the Forstner drill bit, patented on Sept. 22, 1874, was to make him a rich man. Back in those days a brace was traditionally used as a drill machine. It was powered by muscular strength. Therefore the drill had a gimlet point generating automatically a feed at a peripheral rotation. This was perfect for through bore-holes but not very appropriate for stud holes, like those found in old firearms. Hence, the invention of Mr. Forster came in the nick of time. The Forstner bit was unsurpassed in drilling an extremely smooth-sided, flat-bottomed bore hole. Without the conventional wood screw-drill, it would prove especially useful to gunsmiths. Through lucrative royalty payments Benjamin Forstner became a wealthy citizen of Salem (Oregon). Even today, the traditional Forstner drill continues to be manufactured. -

Study Guide: Hand Tools

STUDY GUIDE: HAND TOOLS Learning Objectives: • The features and benefits of the products you sell. • How to answer your customers’ product-related questions. • How to help your customer choose the right products. • How to increase transaction sizes by learning more about add-on sales and upselling techniques. Chapter 1: Fastening Tools Module 1: Hammers Product Knowledge: Claw Hammer • Use for general carpentry, household chores and nail pulling. • Curved claw offers leverage in removing nails. • Use only with non-hardened, common or finishing nails. • You can choose 16 or 20 oz. weights for general carpentry. For fine cabinetry or light- duty driving, choose 7, 10 and 13 oz. nail weights. • Available with a smooth face for finishing jobs, or a waffled face for more control when hammering large nails into lumber. Framing (Rip) Hammer • Use for ripping apart wooden components and demolition work. • Use only with non-hardened, common or finishing nails. • Choose weights from 20 to 32 oz. for framing and ripping. • Available with milled or waffled faces to grip the nail head and reduce the effect of glancing blows and flying nails. Ball Peen (Ball Pein) Hammer • Use with cold chisels for riveting, center punching and forming unhardened metal work. • Striking face diameter should be about 3/8” larger than the diameter of the head of the object being struck. • Popular sizes are 12 and 16 oz. • Variations include a cross-peen hammer (with a horizontal wedge-shaped face) and a straight-peen hammer (with a vertical wedge-shaped face). Sledgehammer • Use for jobs that require great force, such as breaking up concrete or driving heavy spikes.