RACHMANINOFF Piano Concerto No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folleto VRS 2139

Il Clarinetto Piccolo all’Opera Música italiana del siglo XIX para clarinete piccolo y piano Davide Bandieri clarinete piccolo Duncan Gifford piano Javier Balaguer Doménech clarinete en sib Il Clarinetto Piccolo all’Opera 1 Giacomo Panizza 1803-1860 / Ernesto Cavallini 1807-1874 Passo a due eseguito nel ballo “I figli di Eduardo IV” del sig. Cortesi [10:45] 2 Ernesto Cavallini Il Carnevale di Venezia [7:18] Ai miei genitori, 3 Giuseppe Cappelli SIGLO XIX Ruy Blas di F. Marchetti - Fantasia [5:40] Roberto e Lidia. 4 Ernesto Cavallini Grazie Canzone napolitana con tarantella [8:08] 5 Giuseppe Cappelli Piccolo mosaico sull’Opera “Faust” di C. Gounod [5:56] 6 Giacomo Panizza Ballabile con Variazioni nel Ballo “Ettore Fieramosca” [6:21] 7 Luigi bassi 1833-1871 Gran duetto concertato sopra motivi dell’Opera “La Sonnambula” [14:16] (para clarinete piccolo, clarinete en Sib y piano) ESPAÑOL ESPAÑOL IL CLARINETTO PICCOLO ALL’OPERA Crussel (1775-1838), Johann Simon Hernstedt comienzan a integrarse en las formaciones intérprete, sino también como compositor; ade - Música italiana del siglo XIX (1778-1846) y Heinrich Baermann (1784- orquestales y a ser empleados como instru - más de sus famosas composiciones para clari - para clarinete piccolo y piano 1847), cuyos conciertos para clarinete y fan - mentos solistas. En los conservatorios es habi - nete, Adagio y tarantella , Adagio sentimental , tasías operísticas llegaron a ser imprescindi - tual que también se estudie la técnica de estos fantasías, y sus treinta caprichos, Cavallini El mundo operístico en general, y el italiano en bles en los programas para clarinete durante instrumentos, y por tanto surge la necesidad de también compuso obras para clarinete requin - particular, ha sido fuente inagotable de inspi - la primera mitad del XIX. -

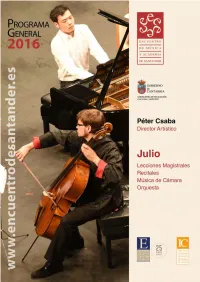

Programa2016.Pdf

l Encuentro de Música y Academia cumple un año más el reto de superarse a sí mismo. La programación de 2016 combina a la perfección la academia, la experiencia y el virtuosismo de los más grandes, como el maestro Krzysztof Penderecki, con la frescura, las ganas y el entusiasmo de los jóvenes músicos Eparticipantes en esta cita ineludible cada verano en Cantabria. Más de 50 conciertos en los escenarios del Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, en el Palacio de La Magdalena y en otras 22 localidades acercarán la Música con mayúsculas a todos los rincones de la Comunidad Autónoma para satisfacer a un público exigente y siempre ávido de manifestaciones culturales. Para esta tierra, es un privilegio la oportunidad de engrandecer su calendario cultural con un evento de tanta relevancia nacional e internacional. Así pues, animo a todos los cántabros y a quienes nos visitan en estas fechas estivales a disfrutar al máximo de los grandes de la música y a aportar con su presencia la excelente programación que, un verano más, nos ofrece el Encuentro de Música y Academia. Miguel Ángel Revilla Presidente del Gobierno de Cantabria esde hace ya 16 años, el Encuentro de Música y Academia de Santander sigue fielmente las líneas maestras que lo han convertido en un elemento muy prestigioso del verano musical europeo. En Santander —que es una delicia en el mes de julio— se reúnen jóvenes músicos seleccionados uno a uno mediante audición en las escuelas de mayor prestigio Dde Europa, incluida, naturalmente, la Reina Sofía de Madrid. Comparten clases magistrales, ensayos y conciertos con una serie igualmente extraordinaria de profesores, los más destacados de cada instrumento en el panorama internacional. -

GEOFFREY TOZER in CONCERT Osaka 1994

GEOFFREY TOZER IN CONCERT Osaka 1994 Mozart Concerto K 467 • Liszt Raussian Folk Song + Rigoletto + Nighingale Geoffrey Tozer in Concert | Osaka 1994 Osaka Symphony Orchestra Wolfgang Amedeus Mozart (1756-1791) Concerto for Piano and Orchestra no. 21 in C, K 467 1 Allegro 13’34” 2 Romance 6’40” 3 Rondo. Allegro assai 7’14” Franz Liszt (1811-1886) 4 Russian Folk Song 2’55” 5 Rigoletto 6’44” 6 Nightingale 4’04” Go to move.com.au for program notes for this CD, and more information about Geoffrey Tozer There are more concert recordings by Geoffrey Tozer … for details see: move.com.au P 2014 Move Records eoffrey Tozer was an artist of Churchill Fellowship (twice, Australia), MBS radio archives in Melbourne and the first rank, a consummate the Australian Creative Artists Fellowship Sydney, the BBC archives in London and musician, a concert pianist (twice, Australia), the Rubinstein Medal in archives in Israel, China, Hungary, and recitalist with few peers, (twice, Israel), the Alex de Vries Prize Germany, Finland, Italy, Russia, Mexico, Gpossessing perfect pitch, a boundless (Belgium), the Royal Overseas League New Zealand, Japan and the United musical memory, the ability to improvise, (United Kingdom), the Diapason d’Or States, form an important part of Tozer’s to transpose instantly into any key or (France), the Liszt Centenary Medallion musical legacy; a gift of national and to create on the piano a richly textured (Hungary) and a Grammy Nomination international importance in music. reduction of an orchestral score at sight. for Best Classical Performance (USA), Throughout his career Tozer resisted He was a superb accompanist and a becoming the only Australian pianist to the frequent calls that he permanently generous collaborator in chamber music. -

Astearte Musikalak 2017 /2018 Denboraldia

noviembre 2017 diciembre 2017 enero 2018 marzo 2018 Día 7 Mikhailova´s Stars Chamber Orchestra Día 5 Amparo Lacruz y Andreu Riera Día 9 Udasoinu Barroco Día 6 Bay Trío Orquesta Misco, 9 componentes Amparo Lacruz, violonchelo 250 años del fallecimiento de G. Ph. Telemann Catalín Bucataru, violín Elena Mikhailova, directora y violín solista Andreu Riera, piano Alberto Itoiz, flauta travesera Joanna Garwacka, trompa Victoria MIkhailova, piano solista Obras de: Bridge, Röntgen y Franck Pilar Azagra, violín María José BaranDíarán, piano Nikola Takov, violín Obras de: Guinovart y Brahms Obras de: Bach, Tchaikovsky, Massenet, Bazzini Carlos Seco, viola y Sarasate Nuria Nieto, violonchelo Día 13 Dúo Guliei - Lavrynenko Elena Muñoz, contrabajo Olena Guliei, violonchelo Astearte Día 14 Jianing Kong, piano Pedro Rodríguez, clavecín Volodymir Lavrynenko, piano Concurso Internacional de Piano de Santander Obras de: Telemann y Bach Obras de: Beethoven, Britten y Paloma O´Shea Musikalak Brahms Obras de: Beethoven y Chopin Día 16 Jorge Nava, piano Obras de: Beethoven y Scarlatti Día 20 Alumnos del Conservatorio de Música Día 12 Cuarteto Ibérico ‘Jesús Guridi’ Día 23 Ensemble Zaïre Beatriz Gutiérrez, violín Artistas y obras serán dados a conocer oportunamente Saaya Ikenoya, violín Oleg Sort, violín Sergio Suárez, violín Díana Ognevskaya, viola Día 27 Le Muse Italiane 2017/18 Natalia Duarte, viola Svetlana Tovstukha, violonchelo Las ocho estaciones, de Vivaldi a Piazzolla 2017ko azaroak 7 / 2018ko martxoak 27 Alessandra Giovannoli, Le Muse Italiane, orquesta Obras de: Arriaga, Mozart, Beethoven, Dvořák y Granados violonchelo Joaquín Páll Palomares, violín solista Joan Serinyá, bajo Joaquín Palomares, violín solista Obras de: Vivaldi, Bach y Mozart Obras de: Vivaldi y Piazzolla. -

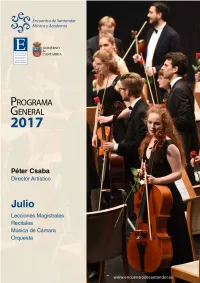

Programa2017.Pdf

l mes de julio trae cada año a Cantabria un nuevo Encuentro de Música y Academia. Son ya 17 las ediciones que cumple una iniciativa que ha convertido la excelencia en su sello Ede garantía al servicio de la formación y la difusión musical. Del 1 al 27 de julio, las aulas del Conservatorio Jesús de Monasterio volverán a acoger a los grandes maestros del panorama internacional para ofrecer un intercambio único a los jóvenes talentos de las doce escuelas europeas más prestigiosas. Un encuentro entre la experiencia de grandísimos artistas consagrados y el entusiasmo y el potencial de las nuevas figuras llamadas a triunfar en los escenarios del futuro. Y junto a la academia, la difusión musical más allá de las aulas para acercar a los cántabros momentos inolvidables en medio centenar de conciertos que llegarán al Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, al Palacio de La Magdalena y la iglesia de Santa Lucía, en Santander, pero también a otra veintena de localidades cántabras, como Torrelavega, Comillas, Santillana del Mar o Laredo. Tenemos por delante un mes para disfrutar de la Música con mayúsculas, desde el concierto inaugural a cargo de la Orquesta Sinfónica Freixenet, dirigida por el maestro Csaba, a los homenajes al pianista Bashkirov y al maestro Rostropovich, pasando por el concierto extraordinario para familias, que acercará la música de Stravinsky al público de todas las edades. Sobran razones y argumentos para sumarse un año más al Encuentro y estoy seguro de que los cántabros y los muchos visitantes que se encuentran entre nosotros en estas fechas estivales sabrán disfrutarlo y valorarlo como merece. -

XX Encuentro De Música Y Academia De Santander Programa General

GOBIERNO de CANTABRIA VICEPRESIDENCIA CONSEJERÍA DE UNIVERSIDADES, IGUALDAD, CULTURA Y DEPORTE / GENERAL PROGRAMME ENCUENTRO DE MÚSICA Y ACADEMIA DE SANTANDER PROGRAMA PROGRAMA GENERAL PROGRAMA GENERAL Tel: +34 942 311 451 / +34 913 511 060 Calle Luis Martínez, 21 2-29 julio 39005 Santander, Cantabria Teléfono: + 34 942 311 451* *Válido del 22 de junio al 25 de julio de 2021 2021 CANTABRIA 2021 CANTABRIA c/ Requena, 1 CANTABRIA 28013 Madrid Teléfono: + 34 913 511 060 Péter Csaba Director artístico [email protected] www.encuentrodesantander.es ENCUENTRO DE MÚSICA Y ACADEMIA DE SANTANDER Y ACADEMIA ENCUENTRO DE MÚSICA www.encuentrodesantander.es ÍNDICE CONTENTS Bienvenida 5 Welcome La Academia 11 The Academy Profesores y participantes 16 Teachers and participants El Escenario 19 The Stage Calendario general 22 General Programme Programas de conciertos 24 Concerts’ Programmes Compositores y obras 89 Composers and Works Biografías 99 Biographies Información práctica 127 Practical Information Agradecimientos 128 Acknowledgements Equipo de gestión 129 Management Team 5 El Encuentro The Music and Academy Encounter returns de Música in July faithful to its appointment, with y Academia a programme that once again perfectly vuelve fiel a combines the academy, the experience and Academy The su cita este virtuosity of the greatest with the freshness, mes de julio, desire and enthusiasm of the young con una musicians participating in this long-awaited programación event in Cantabria. que combina More than 50 concerts will fill with magic de nuevo a / La Academia and sensitivity the stages of the Palace of la perfección Festivals and the Palace of La Magdalena in la academia, Santander and a good number of venues la experiencia y el virtuosismo de los spread over 20 other Cantabrian towns, so más grandes con la frescura, las ganas that Music with capital letters resounds in all y el entusiasmo de los jóvenes músicos corners of our Autonomous Community. -

301278 Vol1.Pdf

INTERPRETATIVE ISSUE PERFO CONTEMPORARY PIANO MUSIC J by\ Philip Thomas (Volume I) Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Performance Practice Department of Music University of Sheffield April 1999 SUMMARY This thesis explores practical and theoretical issues in interpreting contemporary notated piano music. Interpretative problems and approaches are discussed with a practical bias, using a varied selection of musical sources mostly from the last fifty years. The diversity of compositional styles and methods over this period is reflected in the diversity of interpretative approaches discussed throughout this thesis. A feature of the thesis is that no single interpretative method is championed; instead, different approaches are evaluated to highlight their benefits to interpretation, as well as their limitations. It is demonstrated how each piece demands its own approach to interpretation, drawing from different methodologies to varying degrees in order to create a convincing interpretation which reflects the concerns of that piece and its composer. The thesis is divided into four chapters: the first discusses the implications and ambiguities of notation in contemporary music; the second evaluates the importance of analysis and its application to performance and includes a discussion of the existing performance practice literature as well as short performer-based analyses of three pieces (Saxton's Piano Sonata, Tippett's Second Piano Sonata, and Feldman's Triadic Memories); the third chapter considers notions of style and performing traditions, illustrating the factors other than analysis that can 'inform' interpretation; and the fourth chapter draws together the processes demonstrated in the previous chapters in a discussion of the interpretative issues raised by Berio's Seguenza IV. -

A Feldman Chronology by Sebastian Claren

A Feldman Chronology by Sebastian Claren This chronology was originally published in German in, Sebastian Claren, Neither. Die Musik Morton Feldmans (Hofheim: Wolke Verlag, 2000) pp521-544. The English translation by Christine Shuttleworth was first published in, Morton Feldman Says: Selected Interviews and Lectures 1964-1987 (London: Hyphen Press, 2006) pp255-275. The text is made available here by kind permission of Sebastian Claren and Robin Kinross (Hyphen Press). 1926 Morton Feldman is born in Manhattan, New York, on 12 January 1926, the second son of Irving Feldman (1892-1982) and his wife Francis (1898-1985); his brother Harold is nine years older. Both parents are from Jewish families and were sent at the respective ages of eleven and three from Kiev in Russia, via Warsaw, to relatives in New York. Feldman’s father works as a foreman in a clothing company in Manhattan owned by his elder brother. Later, in the early 1940s he succeeds in making himself independent, with a company making children’s coats in Woodside, Queens (5202 39th Avenue), where Feldman grows up. Feldman later related that he had grown up in a wonderful middle- class environment in the suburbs of New York, in a very conventional apartment with conventional furniture.1 1935 At the age of nine, Feldman begins to compose; he takes piano lessons at the Third Street Settlement School on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. 1938 Aged twelve, Feldman is taught piano by Vera Maurina Press, the daughter of a well-off Russian attorney, who had been a friend of the wife of Alexander Scriabin, had studied in Germany with Ferruccio Busoni, Emil von Sauer and Ignaz Friedman, and founded the Russian Trio with her husband Michael Press and his brother David. -

November 2020

OCTOBER - NOVEMBER 2020 คณะกรรมการบริหารสถานีวิทยุจุฬาฯ ประวัติรายการดนตรีคลาสสิก ทีปรึกษา ดร.สุพจน์ เธียรวุฒิ รายการดนตรีคลาสสิกของสถานีวิทยุจุฬาฯ ดําเนินการมา อาจารย์สุภาพร โพธิแก้ว อย่างต่อเนืองเป็นเวลาเกือบ 50 ปี โดยเริมออกอากาศ หลังจากสถานีวิทยุจุฬาฯก่อตงไั ด้ไม่นาน (เมือ พ.ศ. 2508) ประธาน ศาสตราจารย์ นายแพทย์ ดร.นรินทร์ หิรัญสุทธิกุล ผู้จัดทํารายการในระยะแรก คือ คณาจารย์จุฬาฯ และ รองอธิการบดี อาจารย์ดนตรีทีมีใจรักดนตรีคลาสสิก อาทิ ศาสตราจารย์ กรรมการ ดร.กําธร สนิทวงศ์ ณ อยุธยา ศาสตราจารย์ ไขแสง ศุขะ- ศาสตราจารย์ ดร.ปาริชาต สถาปิตานนท์ วัฒนะ ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ สมัยสารท สนิทวงศ์ ณ ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ดร.ณัฐชานนท์ โกมุทพฒิพงศุ ์ อยุธยา และอาจารย์ ปิยะพันธ์ สนิทวงศ์ เป็นต้น อาจารย์ ดร.อลงกรณ์ ปริวุฒิพงศ์ ตังแต่ปี พ.ศ.2511 อาจารย์ ชัชวาลย์ ทาสุคนธ์ และ อาจารย์ สรายุทธ ทรัพย์สุข อาจารย์ สมโภช รอดบุญ ซึงเป็นเจ้าหน้าทีประจําของ นางสาวอรนุช อนุศักดิเสถียร สถานีรับช่วงดําเนินรายการต่อมา อาจารย์ สมโภช ถึงแก่ นายณรงค์ สุทธิรักษ์ กรรมในปี พ.ศ.2531 และทางสถานีได้ดําเนินงานต่อมา รักษาการ กรรมการผ้อูํานวยการสถานี โดยได้ รับความร่วมมือจากบุคลากรผู้ทรงคุณวุฒิหลาย อาจารย์ สุภาพร โพธิแก้ว ท่านของจุฬาฯ ตังแต่ปี พ.ศ. 2533 สีส้ ม เอียมสรรพางค์ และ สดับพิณ รัตนเรือง รับช่วงดําเนินงานต่อมาจนถึงปัจจุบัน รายการ จุลสารรายสองเดือน Music of the Masters เป็นของ ดนตรีคลาสสิกออก อากาศทุกคืน ระหว่างเวลา 22:00 - สถานีวิทยุแห่งจุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย บทความที 24:00 น. ตีพิมพ์ในจุลสารและบทวิทยุของรายการดนตรีคลาสสิก เป็นลิขสิทธิของผู้ จัดทํา ห้ ามผู้ใดนําไปตีพิมพ์หรื อ สถานีวิทยุจุฬาฯได้ ปิ ดรับสมัครสมาชิกรายการดนตรี เผยแพร่ซาในํ ทุกๆ ส่วน คลาสสิกและการจัดส่งจุลสาร Music -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers Q-Z PRIAULX RAINIER (1903-1986) Born in Howick, Natal, South Africa. She sudied violin at the South African College of Music in Capetown and later in London at the Royal Academy of Music. At the latter school she also studied composition with John McEwen and subsequently joined its staff as a professor of composition. In Paris she was also taught by Nadia Boulanger. Among her other orchestral works are a Sinfonia da Camera, Violin Concerto and a Dance Concerto "Phala-Phala." Cello Concerto (1963-4) Jacqueline du Pré (cello)/Norman del Mar/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1964) ( + Elgar: Cello Concerto and Rubbra: Cello Sonata) BBC LEGENDS BBCL 42442 (2008) THOMAS RAJNA (b. 1928) Born in Budapest. He studied at the Franz Liszt Academy under Zoltan Kódaly, Sándor Veress and Leó Weiner. He went to London in 1947 where he studied at the Royal College of Music with Herbert Howells and later on had teaching position at the Guildhall School of Music and the University of Surrey. In 1970 he relocated to South Africa to accept a position at the University of Cape Town. He became a well- known concert pianist and composed for orchestra, chamber groups and voice. For orchestra there is also a Clarinet Rhapsody and a Suite for Strings. Piano Concerto No. 1 (1960-2) Thomas Rajna (piano)/Edgar Cree/South African Broadcasting Corporation Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1974) ( + 11 Preludes and Capriccio) AMARANTHA RECORDS 014 (2001) (original LP release: CLAREMONT GSE 602) (1985) Piano Concerto No. -

Toru Takemitsu” Held in Tokyo (August)

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 T#ru Takemitsu: The Roots of His Creation Haruyo Sakamoto Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLOR IDA STATE UN IV ERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC TRU TAKEMITSU: THE ROOTS OF HIS CREATION By HARUYO SAKAMOTO A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Haruyo Sakamoto defended on December 10, 2002. __________________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo Professor Directing Treatise __________________________________ Victoria McArthur Outside Committee Member __________________________________ Carolyn Bridger Committee Member __________________________________ James Streem Committee Member Approved: _______________________________________________________________________ Seth Beckman, Assistant Dean, School of Music The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above-named committee members. In memory of my mother whose love and support made it possible for me to complete my studies With all my love and appreciation iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deepest appreciation to Professor Leonard Mastrogiacomo for his encouragement, support, and insightful advice for the completion of this treatise. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, Dr. Carolyn Bridger, Dr. Victoria McArthur, and Professor James Streem for their generous help, cooperation, and guidance. Dr. and Mrs. Stephen Van Camerik have been kind enough to offer assistance as editors. Lastly, but not least, I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my family and friends, who stood by me with love and understanding. -

December 2017

DECEMBER 2017 คณะกรรมการบริหารสถานีวิทยุแห่ง ประวัติรายการดนตรีคลาสสิก จุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย ทีป รึกษา รายการดนตรีคลาสสิกของสถานีวิทยุจุฬาฯ ดําเนินการมา อย่างต่อเนืองเป็นเวลาเกือบ 50 ปี โดยเริมออกอากาศ ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ขวัญเรือน กิติวัฒน์ หลังจากสถานีวิทยุจุฬาฯก่อตงไั ด้ไม่นาน ประธาน (สถานีวิทยุจุฬาฯ ก่อตังเมือปี พ.ศ. 2508) ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ดร.พิรงรอง รามสูต รองอธิการบดี ผู้จัดทํารายการในระยะแรก คือ คณาจารย์จุฬาฯ และ อาจารย์ดนตรีทีมีใจรักดนตรีคลาสสิก อาทิ ศาสตราจารย์ กรรมการ ดร.กําธร สนิทวงศ์ ณ อยุธยา ศาสตราจารย์ ไขแสง ศุขะ- ศาสตราจารย์ ดร.ปาริชาต สถาปิตานนท์ วัฒนะ ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ สมัยสารท สนิทวงศ์ ณ อาจารย์สุภาพร โพธิแก้ว อยุธยา และอาจารย์ ปิยะพันธ์ สนิทวงศ์ เป็นต้น ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ดร.ณัฐชานนท์ โกมุทพุฒิพงศ์ อาจารย์ ดร.อลงกรณ์ ปริวุฒิพงศ์ ตังแต่ปี พ.ศ.2511 อาจารย์ ชัชวาลย์ ทาสุคนธ์ และ นางสาวอรนุช อนุศักดิเสถียร อาจารย์ สมโภช รอดบุญ ซึงเป็นเจ้าหน้าทีประจําของ นายณรงค์ สุทธิรักษ์ สถานีรับช่วงดําเนินรายการต่อมา อาจารย์ สมโภช ถึงแก่ กรรมในปี พ.ศ.2531 และทางสถานีได้ดําเนินงานต่อมา โดยได้ รับความร่วมมือจากบุคลากรผู้ทรงคุณวุฒิหลาย ท่านของจุฬาฯ จุลสารรายสองเดือน Music of the Masters เป็นของ สถานีวิทยุแห่งจุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย (FM 101.5 ตังแต่ปี พ.ศ. 2533 สีส้ ม เอียมสรรพางค์ และ สดับพิณ MHz) บทความทีตีพิมพ์ในจุลสารและบทวิทยุของ รัตนเรือง รับช่วงดําเนินงานต่อมาจนถึงปัจจุบัน และตังแต่ รายการดนตรีคลาสสิกเป็นลิขสิทธิของผู้ จัดทํา ห้ามผใดู้ ปี พ.ศ.2536 เป็ นต้นมา รายการดนตรีคลาสสิกออก นําไปตีพิมพ์หรือเผยแพร่ซาในํ ทุกๆ ส่วน อากาศทุกคืน ระหว่างเวลา 21:35-23:55 น. ผ้จู ัดทํา : สดับพิณ รัตนเรือง ปลายปี พ.ศ.2538 ทางรายการเปิดรับสมัครสมาชิกราย