Repeated Elevational Transitions in Hemoglobin Function During the Evolution of Andean Hummingbirds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basilinna Genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an Evaluation Based on Molecular Evidence and Implications for the Genus Hylocharis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 797-807, 2014 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.35769 The Basilinna genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an evaluation based on molecular evidence and implications for the genus Hylocharis El género Basilinna (Aves: Trochilidae): una evaluación basada en evidencia molecular e implicaciones para el género Hylocharis Blanca Estela Hernández-Baños1 , Luz Estela Zamudio-Beltrán1, Luis Enrique Eguiarte-Fruns2, John Klicka3 and Jaime García-Moreno4 1Museo de Zoología, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70- 399, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 2Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70-275, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 3Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Box 353010, Seattle, WA, USA. 4Amphibian Survival Alliance, PO Box 20164, 1000 HD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [email protected] Abstract. Hummingbirds are one of the most diverse families of birds and the phylogenetic relationships within the group have recently begun to be studied with molecular data. Most of these studies have focused on the higher level classification within the family, and now it is necessary to study the relationships between and within genera using a similar approach. Here, we investigated the taxonomic status of the genus Hylocharis, a member of the Emeralds complex, whose relationships with other genera are unclear; we also investigated the existence of the Basilinna genus. We obtained sequences of mitochondrial (ND2: 537 bp) and nuclear genes (AK-5 intron: 535 bp, and c-mos: 572 bp) for 6 of the 8 currently recognized species and outgroups. -

Identifying and Mapping Cell-Type-Specific Chromatin PNAS PLUS Programming of Gene Expression

Identifying and mapping cell-type-specific chromatin PNAS PLUS programming of gene expression Troels T. Marstranda and John D. Storeya,b,1 aLewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, and bDepartment of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 Edited by Wing Hung Wong, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved January 2, 2014 (received for review July 2, 2013) A problem of substantial interest is to systematically map variation Relating DHS to gene-expression levels across multiple cell in chromatin structure to gene-expression regulation across con- types is challenging because the DHS represents a continuous ditions, environments, or differentiated cell types. We developed variable along the genome not bound to any specific region, and and applied a quantitative framework for determining the exis- the relationship between DHS and gene expression is largely tence, strength, and type of relationship between high-resolution uncharacterized. To exploit variation across cell types and test chromatin structure in terms of DNaseI hypersensitivity and genome- for cell-type-specific relationships between DHS and gene expres- wide gene-expression levels in 20 diverse human cell types. We sion, the measurement units must be placed on a common scale, show that ∼25% of genes show cell-type-specific expression ex- the continuous DHS measure associated to each gene in a well- plained by alterations in chromatin structure. We find that distal defined manner, and all measurements considered simultaneously. regions of chromatin structure (e.g., ±200 kb) capture more genes Moreover, the chromatin and gene-expression relationship may with this relationship than local regions (e.g., ±2.5 kb), yet the local only manifest in a single cell type, making standard measures of regions show a more pronounced effect. -

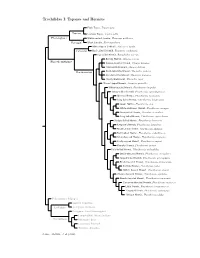

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Nesting Behavior of Reddish Hermits (Phaethornis Ruber) and Occurrence of Wasp Cells in Nests

NESTING BEHAVIOR OF REDDISH HERMITS (PHAETHORNIS RUBER) AND OCCURRENCE OF WASP CELLS IN NESTS YOSHIKA ONIKI REDraSHHermits (Phaethornisruber) are small hummingbirdsof the forested tropical lowlands east of the Andes and south of the Orinoco (Meyer de Schauensee,1966: 161). Five birds mist-nettedat Belem (1 ø 28' S, 48ø 27' W, altitude 13 m) weighed2.0 to 2.5 g (average2.24 g). I studiedtheir nestingfrom 14 October1966 to October1967 at Belem, Brazil, in the Area de PesquisasEco16gicas do Guam•t (APEG) and MocamboForest reserves,in the Instituto de Pesquisase Experimentaqfio Agropecu•triasdo Norte (IPEAN). Names of forest types used and the Portugueseequivalents are: tidal swamp forest (vdrze'a), mature upland forest (terra-/irme) and secondgrowth (capoeira). In all casescapo.eira has been in mature upland situations. At Belem Phaethornisruber is commonall year in the lower levels of secondgrowth (capoeira) where thin branchesare plentiful. Isolated males call frequently from thin horizontal branches,never higher than 2.5-3.0 m. The male sits erect and wags his tail forward and backward as he squeaksa seriesof insectlike"pi-pi-pipipipipipi" notes, 18-20 times per minute; the first two or three notesare short and separated,the rest are run togetherrapidly. The bird sometimesstops calling for someseconds and flasheshis tongue in and out several times during the interval. I foundno singingassemblies of malehermits such as Davis (1934) describes for both the Reddishand Long-tailedHermits (Phaethornissuperciliosus). and Snow (1968) for the Little Hermit (P. longuemareus). Breeding season.--The monthly rainfall at Belem in the year of the study was 350 to 550 mm from January to May and 25 to 200 mm from June to December,with lows in October and November and highs in March and April. -

![Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/downloaded-from-birdtree-org-48-to-take-into-account-phylogenetic-uncertainty-in-the-comparative-analyses-67-245125.webp)

Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: preprint Posted: 15th November 2019 Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine Recommender: Sébastien Lavergne Andraud4, Serge Berthier5, Claire Doutrelant1, & Doris Reviewers: Gomez1,5 XXX Correspondence: 1 [email protected] CEFE, Univ Montpellier, CNRS, Univ Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EPHE, IRD, Montpellier, France 2 ISYEB, CNRS, MNHN, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 45 rue Buffon CP50, Paris, France 3 Grupo de Ecología y Evolución de Vertrebados, Instituto de Biología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia 4 CRC, MNHN, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, CNRS, Paris, France 5 INSP, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Paris, France This article has been peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology 1 of 33 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification among co-occurring species, resulting from character displacement. -

Brown2009chap67.Pdf

Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds (Apodiformes) Joseph W. Browna,* and David P. Mindella,b Hirundinidae, Order Passeriformes), and between the aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology & University nectivorous hummingbirds and sunbirds (Family Nec- of Michigan Museum of Zoology, 1109 Geddes Road, University tariniidae, Order Passeriformes), the monophyletic sta- b of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1079, USA; Current address: tus of Apodiformes has been well supported in all of the California Academy of Sciences, 55 Concourse Drive Golden Gate major avian classiA cations since before Fürbringer (3). Park, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed (josephwb@ A comprehensive historical review of taxonomic treat- umich.edu) ments is available (4). Recent morphological (5, 6), genetic (4, 7–12), and combined (13, 14) studies have supported the apodiform clade. Although a classiA cation based on Abstract large DNA–DNA hybridization distances (4) promoted hummingbirds and swiJ s to the rank of closely related Swifts, treeswifts, and hummingbirds constitute the Order orders (“Trochiliformes” and “Apodiformes,” respect- Apodiformes (~451 species) in the avian Superorder ively), the proposed revision does not inP uence evolu- Neoaves. The monophyletic status of this traditional avian tionary interpretations. order has been unequivocally established from genetic, One of the most robustly supported novel A ndings morphological, and combined analyses. The apodiform in recent systematic ornithology is a close relation- timetree shows that living apodiforms originated in the late ship between the nocturnal owlet-nightjars (Family Cretaceous, ~72 million years ago (Ma) with the divergence Aegothelidae, Order Caprimulgiformes) and the trad- of hummingbird and swift lineages, followed much later by itional Apodiformes. -

The Behavior and Ecology of Hermit Hummingbirds in the Kanaku Mountains, Guyana

THE BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS IN THE KANAKU MOUNTAINS, GUYANA. BARBARA K. SNOW OR nearly three months, 17 January to 5 April 1970, my husband and I F camped at the foot of the Kanaku Mountains in southern Guyana. Our camp was situated just inside the forest beside Karusu Creek, a tributary of Moco Moco Creek, at approximately 80 m above sea level. The period of our visit was the end of the main dry season which in this part of Guyana lasts approximately from September or October to April or May. Although we were both mainly occupied with other observations we hoped to accumulate as much information as possible on the hermit hummingbirds of the area, particularly their feeding niches, nesting and social organization. Previously, while living in Trinidad, we had studied various aspects of the behavior and biology of the three hermit hummingbirds resident there: the breeding season (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1964)) the behavior at singing assemblies of the Little Hermit (Phaethornis Zonguemareus) (D. W. Snow, 1968)) the feeding niches (B. K. Snow and D. W. Snow, 1972)) the social organization of the Hairy Hermit (Glaucis hirsuta) (B. K. Snow, 1973) and its breeding biology (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1973)) and the be- havior and breeding of the Guys’ Hermit (Phuethornis guy) (B. K. Snow, in press). A total of six hermit hummingbirds were seen in the Karusu Creek study area. Two species, Phuethornis uugusti and Phaethornis longuemureus, were extremely scarce. P. uugusti was seen feeding once, and what was presumably the same individual was trapped shortly afterwards. -

Threatened Birds of the Americas

TANAGER-FINCH Oreothraupis arremonops V/R10 This cloud-forest undergrowth species has a poorly known and patchy distribution in the West Andes of Colombia and in north-western Ecuador, with few recent records. However, large tracts of apparently suitable habitat remain in protected areas, the reason for its apparent rarity being essentially unknown. DISTRIBUTION The Tanager-finch (see Remarks 1) is known from just a few apparently disjunct areas on the West Andes in Antioquia, Valle, Cauca and Nariño departments, Colombia, and also from Imbabura and Pichincha provinces, north-western Ecuador, where localities (coordinates from Paynter and Traylor 1977, 1981) are as follows: Colombia (Antioquia) Hacienda Potreros (c.6°39’N 76°09’W; on the western slope of the West Andes, south-west of Frontino), where a male (in USNM) was taken at 1,980 m in June 1950 (also Carriker 1959); (Valle) in the region of Alto Anchicayá (c.3°37’N 76°53’W), where the species has fairly recently been recorded (Orejuela 1983); (Cauca) in the vicinity of Cerro Munchique (2°32’N 76°57’W), where the bird is regularly found on the western slope (Hilty and Brown 1986), specific localities including: La Costa (untraced, but c.10 km north of Cerro Munchique), where a female (in ANSP) was taken at 1,830 m in March 1938 (also Meyer de Schauensee 1948-1952), Cocal (2°31’N 77°00’W; north-west of Cerro Munchique), where two specimens were collected at 1,830 m (Chapman 1917a), El Tambo (2°25’N 76°49’W; on the east slope of the West Andes), whence come specimens taken at 1,370 -

Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Sophie Wolbert SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wolbert, Sophie, "Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2470. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2470 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolbert 1 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Author: Wolbert, Sophie Academic -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Adult, Embryonic and Fetal Hemoglobin Are Expressed in Human Glioblastoma Cells

514 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY 44: 514-520, 2014 Adult, embryonic and fetal hemoglobin are expressed in human glioblastoma cells MARWAN EMARA1,2, A. ROBERT TURNER1 and JOAN ALLALUNIS-TURNER1 1Department of Oncology, University of Alberta and Alberta Health Services, Cross Cancer Institute, Edmonton, AB T6G 1Z2, Canada; 2Center for Aging and Associated Diseases, Zewail City of Science and Technology, Cairo, Egypt Received September 7, 2013; Accepted October 7, 2013 DOI: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2186 Abstract. Hemoglobin is a hemoprotein, produced mainly in Introduction erythrocytes circulating in the blood. However, non-erythroid hemoglobins have been previously reported in other cell Globins are hemo-containing proteins, have the ability to types including human and rodent neurons of embryonic bind gaseous ligands [oxygen (O2), nitric oxide (NO) and and adult brain, but not astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. carbon monoxide (CO)] reversibly. They have been described Human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most aggres- in prokaryotes, fungi, plants and animals with an enormous sive tumor among gliomas. However, despite extensive basic diversity of structure and function (1). To date, hemoglobin, and clinical research studies on GBM cells, little is known myoglobin, neuroglobin (Ngb) and cytoglobin (Cygb) repre- about glial defence mechanisms that allow these cells to sent the vertebrate globin family with distinct function and survive and resist various types of treatment. We have tissue distributions (2). During ontogeny, developing erythro- shown previously that the newest members of vertebrate blasts sequentially express embryonic {[Gower 1 (ζ2ε2), globin family, neuroglobin (Ngb) and cytoglobin (Cygb), are Gower 2 (α2ε2), and Portland 1 (ζ2γ2)] to fetal [Hb F(α2γ2)] expressed in human GBM cells. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations.