Nesting Behavior of Reddish Hermits (Phaethornis Ruber) and Occurrence of Wasp Cells in Nests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

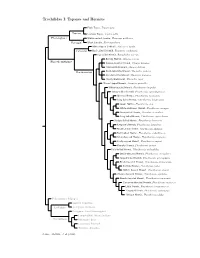

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Observations of Hummingbird Feeding Behavior at Flowers of Heliconia Beckneri and H

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 133–138, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society OBSERVATIONS OF HUMMINGBIRD FEEDING BEHAVIOR AT FLOWERS OF HELICONIA BECKNERI AND H. TORTUOSA IN SOUTHERN COSTA RICA Joseph Taylor1 & Stewart A. White Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Graham Kerr Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, CB23 6DH, UK. Observaciones de la conducta de alimentación de colibríes con flores de Heliconia beckneri y H. tortuosa en El Sur de Costa Rica. Key words: Pollination, sympatric, cloud forest, Cloudbridge Nature Reserve, Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy, Violet Sabrewing, Campylopterus hemileucurus, Green-crowned Brilliant, Heliodoxa jacula. INTRODUCTION sources in a single foraging bout (Stiles 1978). Interactions between closely related sympatric The flower preferences shown by humming- flowering plants may involve competition for birds (Trochilidae) are influenced by a com- pollinators, interspecific pollen loss and plex array of factors including their bill hybridization (e.g., Feinsinger 1987). These dimensions, body size, habitat preference and processes drive the divergence of genetically relative dominance, as influenced by age and based floral phenotypes that influence polli- sex, and how these interact with the morpho- nator assemblages and behavior. However, logical, caloric and visual properties of flow- floral convergence may be favored if the ers (e.g., Stiles 1976). increased nectar supplies and flower densities, Hummingbirds are the primary pollina- for example, increase the regularity and rate tors of most Heliconia species (Heliconiaceae) of flower visitation for all species concerned (Linhart 1973), which are medium to large (Schemske 1981). Sympatric hummingbird- clone-forming herbs that usually produce pollinated plants probably face strong selec- brightly colored floral bracts (Stiles 1975). -

Project Scientific Progress Report Study Site

Project Ecology of plant-hummingbird interactions along an elevational gradient Scientific Progress Report Project leader: Catherine Graham, Swiss Federal Research Institute Principal investigator: María Alejandra Maglianesi, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Coordinator: Emanuel Brenes Rodríguez, Universidad Estatal a Distancia Study site Las Nubes Biological Reserve York University San José, Costa Rica January, 2020 1 INTRODUCTION A primary aim of community ecology is to identify the processes that govern species assemblages across environmental gradients (McGill et al. 2006), allowing us to understand why biodiversity is non-randomly distributed on Earth. Mutualistic interactions such as those between plants and their animal pollinators are the major biodiversity component from which the integrity of ecosystems depends (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2015). The interdependence of plant and pollinators can be assessed using a network approach, which is a powerful tool to analyze the complexity of ecological systems (Ings et al. 2009), especially in highly diversified tropical regions. Mountain regions provide pronounced environmental gradients across relatively small spatial scales and have proved to be a suitable model system to investigate patterns and determinants of species diversity and community structure (Körner 2000, Sanders and Rahbek 2012). Although some studies have investigated the variation in plant–pollinator interaction networks across elevational gradients (Ramos-Jiliberto et al. 2010, Benadi et al. 2013), such studies are still scarce, particularly in the tropics. In the Neotropics, hummingbirds (Trochilidae) are considered to be effective pollinators (Castellanos et al. 2003). They have been classified into two distinct groups: hermits and non-hermits, which differ mainly in their elevational distribution and their level of specialization on floral resources, i.e., the proportion of floral resources available in the community that is used by species (Stiles 1978). -

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo Areas, Loreto, Peru

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo areas, Loreto, Peru Compiled by Carol R. Foss, Ph.D. and Josias Tello Huanaquiri, Guide Status based on expeditions from Tahuayo Logde and Amazonia Research Center TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1. Great Tinamou Tinamus major 2. White- throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus 3. Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus 4. Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 5. Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulates 6. Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus 7. Bartlett’s Tinamou Crypturellus bartletti ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 8. Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 9. Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 10. Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 11. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 12. Spix’s Guan Penelope jacquacu 13. Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile cumanensis 14. Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 15. Wattled Curassow Crax globulosa 16. Razor-billed Curassow Mitu tuberosum GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 17. Marbled Wood-Quall Odontophorus gujanensis 18. Starred Wood-Quall Odontophorus stellatus PELECANIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus PELECANIFORMES: Anhingidae 20. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga CICONIIFORMES: Ardeidae 21. Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma lineatum 22. Agami Heron Agamia agami 23. Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 24. Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus 25. Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax 26. Striated Heron Butorides striata 27. Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 28. Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi 29. Great Egret Ardea alba 30. Cappet Heron Pilherodius pileatus 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula 32. Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea CICONIIFORMES: Threskiornithidae 33. Green Ibis Mesembrinibis cayennensis 34. Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 35. Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 36. Wood Stork Mycteria Americana CICONIIFORMES: Cathartidae 37. Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 38. Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus 39. -

The Behavior and Ecology of Hermit Hummingbirds in the Kanaku Mountains, Guyana

THE BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS IN THE KANAKU MOUNTAINS, GUYANA. BARBARA K. SNOW OR nearly three months, 17 January to 5 April 1970, my husband and I F camped at the foot of the Kanaku Mountains in southern Guyana. Our camp was situated just inside the forest beside Karusu Creek, a tributary of Moco Moco Creek, at approximately 80 m above sea level. The period of our visit was the end of the main dry season which in this part of Guyana lasts approximately from September or October to April or May. Although we were both mainly occupied with other observations we hoped to accumulate as much information as possible on the hermit hummingbirds of the area, particularly their feeding niches, nesting and social organization. Previously, while living in Trinidad, we had studied various aspects of the behavior and biology of the three hermit hummingbirds resident there: the breeding season (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1964)) the behavior at singing assemblies of the Little Hermit (Phaethornis Zonguemareus) (D. W. Snow, 1968)) the feeding niches (B. K. Snow and D. W. Snow, 1972)) the social organization of the Hairy Hermit (Glaucis hirsuta) (B. K. Snow, 1973) and its breeding biology (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1973)) and the be- havior and breeding of the Guys’ Hermit (Phuethornis guy) (B. K. Snow, in press). A total of six hermit hummingbirds were seen in the Karusu Creek study area. Two species, Phuethornis uugusti and Phaethornis longuemureus, were extremely scarce. P. uugusti was seen feeding once, and what was presumably the same individual was trapped shortly afterwards. -

Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Sophie Wolbert SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wolbert, Sophie, "Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2470. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2470 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolbert 1 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Author: Wolbert, Sophie Academic -

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia Beckneri and H

Do Sympatric Heliconias Attract the Same Species of Hummingbird? Observations on the Pollination Ecology of Heliconia beckneri and H. tortuosa at Cloudbridge Nature Reserve Joseph Taylor University of Glasgow The Hummingbird-Heliconia Project The hummingbird family (Trochilidae), endemic to the Neotropics, is remarkable not only for its beauty but also because of its ability to hover over a flower while feeding, its wing movements a blur. These lively birds require frequent, nutritious feeding to sustain their expenditure of energy, and some plants have evolved to attract and feed them in exchange for pollination services. Prominent among such plants are most species in the genus Heliconia (Heliconiaceae), which are medium to large clone-forming herbs with banana-like leaves (Stiles, 1975). The hummingbird-Heliconia interdependence is a good example of co- evolution, and this study is concerned with one aspect of this relationship. Since several species of hummingbird and Heliconia exist at Cloudbridge, a middle-elevation nature reserve in Costa Rica, we wondered whether particular species of Heliconia had evolved an attraction for particular hummingbird species, which might reduce the chances of hybridisation and pollen loss; or whether the plants compete for a variety of hummingbirds. At Cloudbridge, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica’s Talamanca mountain range, Heliconia beckneri , an endangered species (website 1) restricted to this area and thought to be of hybrid origin (Daniels and Stiles, 1979; website 2), and H. tortuosa occur together. Stiles (1979) names the Green Hermit ( Phaethornis guy ) as the primary pollinator of both species and the Violet Sabrewing ( Campylopterus hemileucurus ) as the secondary pollinator of H. -

Hermit Crab MEASUREMENT: UNITS and TOOLS • Common Curriculum Goal: Select and Use Appropriate Standard and Nonstandard Units and Tools of Measurement

Lab Program Curriculum Grades K-8 2 Program Description This 45-60 minute lab begins with a discussion about the conditions of the rocky intertidal zone, led by one of our education staff members. Students and their chaperones will then travel to four stations where they will learn about some of the adaptations of four marine invertebrates from this habitat. Participating in this program will help your student to meet the grade three common curriculum goals and benchmarks listed on the following pages of this packet. Chaperones will be asked to take an active role in the lab program, which is designed so that they read informational cards in English to the students in their group. It will also be the chaperone’s responsibility to monitor the students’ behavior during the lab program. Before your visit: • Use the What About the Ocean? And the Recipe for an Ocean activities to find out how much your students already know about the ocean and what they would like to learn. • Using pictures from magazines or drawings make ocean plant and animal cards. Use these and the enclosed Flash Card Notebook cards to familiarize students with organisms they may see at the Aquarium. Incorporate appropriate vocabulary, play concentration or use them as flash cards for plant and Ochre star animal identification. • Assign the activity How Big Is It? Included in your packet. Use a bar graph to graph the length of each animal. • Discuss how children treat their pets at home. What is proper and improper when handling animals? Discuss how some animals are too delicate to be touched and should only be observed. -

Biodiversity and Conservation of Sierra Chinaja: a Rapid Assessment of Biophysical Socioeconomic and Management Factors in Alta Verapaz Guatemala

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 Biodiversity and conservation of Sierra Chinaja: A rapid assessment of biophysical socioeconomic and management factors in Alta Verapaz Guatemala Curan A. Bonham The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bonham, Curan A., "Biodiversity and conservation of Sierra Chinaja: A rapid assessment of biophysical socioeconomic and management factors in Alta Verapaz Guatemala" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4760. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4760 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of M ontana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature:i _ ________ Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Biodiversity and Conservation of Sierra Chinaja: A r a p id ASSESSMENT OF BIOPHYSICAL, SOCIOECONOMIC, AND MANAGEMENT f a c t o r s in A l t a V e r a p a z , G u a t e m a l a by Curan A. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Frequency of Arthropods in Stomachs of Tropical Hummingbirds

436 ShortCommunications [Auk, Vol. 103 Frequencyof Arthropods in Stomachsof Tropical Hummingbirds J. v. gEMSEN,JR., • F. GARY STILES,2 AND PETERE. SCOTT1 tMuseumof Zoologyand Department of Zoologyand Physiology, Louisiana State University, BatonRouge, Louisiana 70803 USA, and 2Escuelade Biologfa,Universidad de CostaRica, Ciudad Universitaria "Rodrigo Facio," Costa Rica Although flower nectar is the most conspicuous per we do not record in detail the kinds of arthro- and energeticallyefficient food sourceof humming- pods consumed,except insofar as this may affect the birds,it is notablydeficient in amino acidsand other frequency of detectablearthropod remains. A de- essential nutrients (Baker and Baker 1975, Hains- tailed study of the arthropod diets and foraging tac- worth and Wolf 1976). Therefore, hummingbirds re- ticsof hummingbirdsis in preparation(Hespenheide quire an additional source of proteins, lipids, and and Stiles unpubl. data). other nutrients. In most or all species,these nutrients The specimensreported here were collected (1) are obtainedby consumingsmall arthropods.Yet ar- from 1980 to 1985 by personnel of the Museum of thropod-foragingby hummingbirdsremains very lit- Zoology,Louisiana State University (LSUMZ) or (2) tle studied comparedwith nectar-foraging(Gass and from 1971 to 1985 by Stiles and his students.Ap- Montgomerie1981, Hespenheide and Stilesunpubl. proximately 70% of all specimenswere collectedin data). The few available time-budget studies of for- Bolivia or Peru, 25% in Costa Rica, and the remainder aging hummingbirds(reviewed by Gassand Mont- in northwestern Ecuador, Venezuela, or Darign, Pan- gomerie 1981) indicate that arthropod-hunting con- ama.Twenty recentspecimens of 15 speciesfrom Ec- stitutesonly 2-12%of total foragingtime exceptwhen uador and Peru depositedin the Academyof Natural nectar is scarceor unavailable.An incubating female Sciences,Phildelphia, also were included. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed