A Samurai Kills the Provincial Governor and Cuts Him in Two Halves with His Sword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

The Case of Sugawara No Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho''

Ideology and Historiography : The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho'' 著者 PLUTSCHOW Herbert 会議概要(会議名, Historiography and Japanese Consciousness of 開催地, 会期, 主催 Values and Norms, カリフォルニア大学 サンタ・ 者等) バーバラ校, カリフォルニア大学 ロサンゼルス校, 2001年1月 page range 133-145 year 2003-01-31 シリーズ 北米シンポジウム 2000 International Symposium in North America 2014 URL http://doi.org/10.15055/00001515 Ideology and Historiography: The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the Nihongiryaku, Fusi Ryakki and the Gukanshd Herbert PLUTSCHOW University of California at Los Angeles To make victims into heroes is a Japanese cultural phenomenon intimately relat- ed to religion and society. It is as old as written history and survives into modem times. Victims appear as heroes in Buddhist, Shinto, and Shinto-Buddhist cults and in numer- ous works of Japanese literature, theater and the arts. In a number of articles I have pub- lished on this subject,' I tried to offer a religious interpretation, emphasizing the need to placate political victims in order to safeguard the state from their wrath. Unappeased political victims were believed to seek revenge by harming the living, causing natural calamities, provoking social discord, jeopardizing the national welfare. Beginning in the tenth century, such placation took on a national importance. Elsewhere I have tried to demonstrate that the cult of political victims forced political leaders to worship their for- mer enemies in a cult providing the religious legitimization, that is, the mainstay of their power.' The reason for this was, as I demonstrated, the attempt leaders made to control natural forces through the worship of spirits believed to influence them. -

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi No Kumi (Confraria De Misericórdia)

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi no Kumi (Confraria de Misericórdia) Takashi GONOI Professor Emeritus, University of Tokyo Introduction During the 80-year period starting when the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier and his party arrived in Kagoshima in August of 1549 and propagated their Christian teachings until the early 1630s, it is estimated that a total of 760,000 Japanese converted to Chris- tianity. Followers of Christianity were called “kirishitan” in Japanese from the Portu- guese christão. As of January 1614, when the Tokugawa shogunate enacted its prohibi- tion of the religion, kirishitan are estimated to have been 370,000. This corresponds to 2.2% of the estimated population of 17 million of the time (the number of Christians in Japan today is estimated at around 1.1 million with Roman Catholics and Protestants combined, amounting to 0.9% of total population of 127 million). In November 1614, 99 missionaries were expelled from Japan. This was about two-thirds of the total number in the country. The 45 missionaries who stayed behind in hiding engaged in religious in- struction of the remaining kirishitan. The small number of missionaries was assisted by brotherhoods and sodalities, which acted in the missionaries’ place to provide care and guidance to the various kirishitan communities in different parts of Japan. During the two and a half centuries of harsh prohibition of Christianity, the confraria (“brother- hood”, translated as “kumi” in Japanese) played a major role in maintaining the faith of the hidden kirishitan. An overview of the state of the kirishitan faith in premodern Japan will be given in terms of the process of formation of that faith, its actual condition, and the activities of the confraria. -

The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection

NEWS RELEASE November, 2009 The Lineage of Culture – The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection The Tokyo National Museum is pleased to present the special exhibition “The Lineage of Culture—The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection” from Tuesday, April 20, to Sunday, June 6, 2010. The Eisei Bunko Foundation was established in 1950 by 16th-generation family head Hosokawa Moritatsu with the objective of preserving for future generations the legacy of the cultural treasures of the Hosokawa family, lords of the former Kumamoto domain. It takes its name from the “Ei” of Eigen’an—the subtemple of Kenninji in Kyoto, which served as the family temple for eight generations from the time of the original patriarch Hosokawa Yoriari, of the governing family of Izumi province in the medieval period— and the “Sei” of Seiryūji Castle, which was home to Hosokawa Fujitaka (better known as Yūsai), the founder of the modern Hosokawa line. Totaling over 80,000 objects, it is one of the leading collections of cultural properties in Japan and includes archival documents, Yūsai’s treatises on waka poetry, tea utensils connected to the great tea master Sen no Rikyū from the personal collection of 2nd-generation head Tadaoki (Sansai), various objects associated with Hosokawa Gracia, and paintings by Miyamoto Musashi. The current exhibition will present the history of the Hosokawa family and highlight its role in the transmission of traditional Japanese culture—in particular the secrets to understanding the Kokinshū poetry collection, and the cultural arts of Noh theater and the Way of Tea—by means of numerous treasured art objects and historical documents that have been safeguarded through the family’s tumultuous history. -

Ki No Tsurayuki a Poszukiwanie Tożsamości Kulturowej W Literaturze Japońskiej X Wieku

Title: Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku Author: Krzysztof Olszewski Citation style: Olszewski Krzysztof. (2003). Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku. Kraków : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku Literatura, język i kultura Japonii Krzysztof Olszewski Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku WYDAWNICTWO UNIWERSYTETU JAGIELLOŃSKIEGO Seria: Literatura, język i kultura Japonii Publikacja finansowana przez Komitet Badań Naukowych oraz ze środków Instytutu Filologii Orientalnej oraz Wydziału Filologicznego Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego RECENZENCI Romuald Huszcza Alfred M. Majewicz PROJEKT OKŁADKI Marcin Bruchnalski REDAKTOR Jerzy Hrycyk KOREKTOR Krystyna Dulińska © Copyright by Krzysztof Olszewski & Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Wydanie I, Kraków 2003 All rights reserved ISBN 83-233-1660-0 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Dystrybucja: ul. Bydgoska 19 C, 30-056 Kraków Tel. (012) 638-77-83, 636-80-00 w. 2022, 2023, fax (012) 430-19-95 Tel. kom. 0604-414-568, e-mail: wydaw@if. uj. edu.pl http: //www.wuj. pl Konto: BPH PBK SA IV/O Kraków nr 10601389-320000478769 A MOTTO Księżyc, co mieszka w wodzie, Nabieram w dłonie Odbicie jego To jest, to niknie znowu - Świat, w którym przyszło mi żyć. Ki no Tsurayuki, testament poetycki' W świątyni w Iwai Będę się modlił za Ciebie I czekał całe wieki. Choć -

16 Brightwells,Clancarty Rcad,London S0W.6. (O 1-736 6838)

Wmil THE TO—KEN SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN for theStudy and Preservation of Japanese Swords and Fittings Hon.President B.W.Robinson, M0A. ,B,Litt. Secretary: 16 Brightwells,Clancarty Rcad,London S0W.6. 1- 736 6838) xnc2ResIoENTzuna0xomoovLxnun. (o PROGRAMME NEXT MEETING Monday, OOtober 7th 1968 at The Masons Arms 9 Maddox Street 9 London 1-1.1. at 7.30 p.m. SUBJECT Annual meeting in which nominations for the new Committee will be taken, general business and fortunes of the Society discussed. Members please turn up to this important meeting 9 the evening otherwise will be a free for all, so bring along swords, tsuba, etc. for discussion, swopping or quiet corner trading. LAST. MEETING I was unable to attend this and have only reports from other members. I understand that Sidney Divers showed examples of Kesho and Sashi-kome polishes on sword blades, and also the result of a "home polish" on a blade, using correcb polishing stones obtained from Japan, I believe in sixteen different grades0 Peter Cottis gave his talk on Bows and Arrows0 I hope it may be possible to obtain notes from Peter on his talk0 Sid Diverse written remarks can his part in the meeting are as follows "As promised at our last meeting, I have brought examples of good (Sashi-Komi) and cheap (Kesho) • polishes. There are incidentally whole ranges of prices for both types of polish0 The Sashi-Komi polish makes the colour of the Yakiba almost the same as the Jihada. This does bring out all the smallest details of Nie and Nioi which would not show by the Kesho polish. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

Latest Japanese Sword Catalogue

! Antique Japanese Swords For Sale As of December 23, 2012 Tokyo, Japan The following pages contain descriptions of genuine antique Japanese swords currently available for ownership. Each sword can be legally owned and exported outside of Japan. Descriptions and availability are subject to change without notice. Please enquire for additional images and information on swords of interest to [email protected]. We look forward to assisting you. Pablo Kuntz Founder, unique japan Unique Japan, Fine Art Dealer Antiques license issued by Meguro City Tokyo, Japan (No.303291102398) Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Upcoming Sword Shows & Sales Events Full details: http://new.uniquejapan.com/events/ 2013 YOKOSUKA NEX SPRING BAZAAR April 13th & 14th, 2013 kitchen knives for sale YOKOTA YOSC SPRING BAZAAR April 20th & 21st, 2013 Japanese swords & kitchen knives for sale OKINAWA SWORD SHOW V April 27th & 28th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN OKINAWA KAMAKURA “GOLDEN WEEKEND” SWORD SHOW VII May 4th & 5th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN KAMAKURA NEW EVENTS ARE BEING ADDED FREQUENTLY. PLEASE CHECK OUR EVENTS PAGE FOR UPDATES. WE LOOK FORWARD TO SERVING YOU. Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Index of Japanese Swords for Sale # SWORDSMITH & TYPE CM CERTIFICATE ERA / PERIOD PRICE 1 A SADAHIDE GUNTO 68.0 NTHK Kanteisho 12th Showa (1937) ¥510,000 2 A KANETSUGU KATANA 73.0 NTHK Kanteisho Gendaito (~1940) ¥495,000 3 A KOREKAZU KATANA 68.7 Tokubetsu Hozon Shoho (1644~1648) ¥3,200,000 4 A SUKESADA KATANA 63.3 Tokubetsu Kicho x 2 17th Eisho (1520) ¥2,400,000 -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

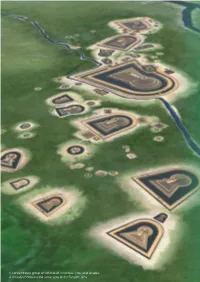

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

![[Original Paper]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9524/original-paper-1069524.webp)

[Original Paper]

A Study on the Location of Castle and Urban Structure of Castle-town by Watershed Based Analysis LIM Luong1, SASAKI Yoh2 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Waseda University (3-4-1 Okubo, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 169-8555, Japan) E-mail:[email protected] 2Member of JSCE, Professor, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Eng., Waseda University (3-4-1 Okubo, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 169-8555, Japan) E-mail:[email protected] This research seeks to identify the urban planning methods for sustainable development by introducting watershed based analysis. From the view point of the ecological aspects, characteristics of Japanese cas- tle-town, JYOKAMACHI, was dedicated as one of important factors to identify urban planning methods. Therefore, the location of castle and its urban structure were investigated. GIS is used to analyze the loca- tion of castle and its urban structure by mean of watershed based analysis. Results showed that among 86 castle locations, about 34% of castle locations of Hilltop, Mountaintop and Flatland is located on the catchment edge, 60% is located near by the catchment edge and 6% is located in the middle of the catch- ment edge. 88% of most of the castle locations was found located at the highest elevation area comparing to its surrounding and within the catchment it’s located. It can be said that most of the castle locations tends to be located at the highest elevation area as a unit of watershed. 10 cases of overlaying maps between urban structure of castle-town in edo period and catchment maps showed that urban structure of castle-town had strong relationship with watershed.