HIV/AIDS Vulnerability of Students at the National University of Lesotho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping, Understanding, and Translating

Appreciating Assets: The Contribution of Religion to Universal Access in Africa Mapping, Understanding, Translating and Engaging Religious Health Assets in Zambia and Lesotho In support of Universal Access to HIV/AIDS Treatment, Care and Prevention Report of The African Religious Health Assets Program (ARHAP) Under Contract to The World Health Organization (WHO) (HQ/05/148454, HQ/05/148467) October 2006 Suggested Reference African Religious Health Assets Programme, "Appreciating Assets: The Contribution of Religion to Universal Access in Africa", Report for the World Health Organization, (Cape Town: ARHAP, October 2006). Contact Information African Religious Health Assets Programme (ARHAP) Interfaith Health Program Dept. of Religious Studies Hubert Department of Global Health University of Cape Town Rollins School of Public Health Private Bag Emory University 7701 1256 Briarcliff Road NE Rondebosch Bldg A, Suite 107 South Africa Atlanta, GA 30319 USA Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Phone: +27 -21 650 3457/8 Phone: 404-727-5246 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary 1 Chapter 1: Considering Religious Health Assets II. Introduction 6 A. Purpose 6 B. Contract Summary 6 C. Research Theory/Approach 7 D. Research Question, Hypothesis, Tools 8 E. Limitations of the Study 8 F. Ethics Clearance 9 G. Time Frame of Study 9 H. Research Teams 10 I. Layout of the Report 11 III. Background 12 A. HIV/AIDS “Situation Report” - Lesotho and Zambia 12 B. Universal Access and Millennium Development Goals: Support and Linkages 18 C. Rationale for Religious Engagement in Universal Access & Millennium Development 19 D. Religion, Health and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Brief Overview of Literature 20 IV. -

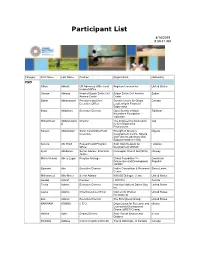

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Perceptions of Mental Illness in South- Eastern Nigeria: Causal Beliefs, Attitudes, Help-Seeking Pathways and Perceived Barriers to Help-Seeking

PERCEPTIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN SOUTH- EASTERN NIGERIA: CAUSAL BELIEFS, ATTITUDES, HELP-SEEKING PATHWAYS AND PERCEIVED BARRIERS TO HELP-SEEKING UGO IKWUKA BA, BSc, MA June 2016 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The exploratory studies of three of the four chapters of this work have been published in peer reviewed journals. SAGE granted an automatic ‘gratis reuse’ for the first publication on causal beliefs that allows for the work to be posted in the repository of the author’s institution. Copyright licence (no. 3883120494543) was obtained from John Wiley and Sons to republish the second paper on attitudes towards mental illness in this dissertation. Copyright licence (no. 3883131164423) was obtained from the John Hopkins University Press to republish the third paper on barriers to accessing formal mental healthcare in this dissertation. The exploratory study on Pathways to Mental Healthcare has been accepted for publication in Transcultural Psychiatry with the proviso that it is part of a doctoral dissertation. Save for any express acknowledgments, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Ugo Ikwuka to be identified as author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature……………………………………….. Date…………………………………………….. Acknowledgments I share the communitarian worldview that ‘a tree cannot make a forest’ which was clearly demonstrated in the collective support that made this research possible. -

Engaging Basotho Diasporas in the South for National Development

OBSERVATORY ON MIGRATION OBSERVATOIRE ACP SUR LES MIGRATIONS OBSERVATÓRIO ACP DAS MIGRAÇÕES UNTAPPED POTENTIAL: Engaging Basotho diasporas in the South for national development Lulessa Abadura Brigitte Fahrenhorst Frank Zelazny EcoDevelopment - Society for International Development Research and Planning Ltd. Research Lesotho mineworkers in South Africa Lesotho mineworkers Report An Initiative of the ACP Secretariat, ACPOBS/2014/PUB06 Funded by the European Union Implemented by IOM and with the Financial Support of Switzerland, IOM, the IOM Development Fund and UNFPA International Organization for Migration (IOM) Organisation internationale pour les migrations (OIM) NETE KE Organização Internacional para as Migrações (OIM) THEBE 2014 ACP Observatory on Migration The ACP Observatory on Migration is an initiative of the Secretariat of the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Group of States, funded by the European Union, implemented by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in a Consortium with 15 partners and with the financial support of Switzerland, IOM, the IOM Development Fund and UNFPA. Established in 2010, the ACP Observatory is an institution designed to produce data on South–South ACP migration for migrants, civil society and policymakers and enhance research capacities in ACP countries for the improvement of the situation of migrants and the strengthening of the migration–development nexus. The Observatory was established to facilitate the creation of a network of research institutions and experts on migration research. Activities are starting in 12 pilot countries and will be progressively extended to other interested ACP countries. The 12 pilot countries are: Angola, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Kenya, Lesotho, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, Timor‐Leste, Trinidad and Tobago and the United Republic of Tanzania. -

Financing Universal Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

FINANCING UNIVERSAL WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE UNDER THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS — UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water, GLAAS 2017 Report and Drinking-Water, of Sanitation and Assessment Analysis Global — UN-Water GOALS DEVELOPMENT UNDER THE SUSTAINABLE AND HYGIENE SANITATION FINANCING UNIVERSAL WATER, FINANCING UNIVERSAL WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE UNDER THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water GLAAS 2017 Report ISBN 978 92 4 151219 0 http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/glaas/en/ contact email: [email protected] FINANCING UNIVERSAL WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE UNDER THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water GLAAS 2017 Report FINANCING UNIVERSAL WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE UNDER THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water GLAAS 2017 Report UN-Water global analysis and assessment of sanitation and drinking-water (GLAAS) 2017 report: financing universal water, sanitation and hygiene under the sustainable development goals ISBN 978-92-4-151219-0 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. -

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: a Celebration and a Challenge

Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and A Challenge In collaboration with: UNDESA, FAO, ILO, OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UN Habitat, UNHCR, UNICEF, UN Women, WFP, WHO, ECA, ECE, ECLAC, ESCAP, ESCWA, GAA, HelpAge USA, IFA, INPEA, IOM Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and A Challenge Published by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), New York, and HelpAge International, London Copyright © United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and HelpAge International, 2012. All rights reserved. United Nations Population Fund 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158, USA [email protected] www.unfpa.org HelpAge International PO Box 70156, London WC1A 9GB, UK [email protected] www.helpage.org Registered charity no. 288180 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of UNFPA or HelpAge International. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of whatsoever on the part of UNFPA and HelpAge International concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The term ‘country’ as used in the text of this report refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. The designations of ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries are intended for convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. ISBN 978-0-89714-981-5 Ageing in the Twenty-First -

Women's Political Participation ~ Africa Barometer 2021

Women'sWomen's PoliticalPolitical ParticipationParticipation AFRICA 2021 Women’s Political Participation ~ Africa Barometer 2021 © 2021 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance ISBN: 978-91-7671-397-6 International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the WL Creative Commons website: SA <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <https://www.idea.int> Design and layout: Debi Lee Editors: Colleen Lowe Morna, Susan Tolmay and Mukayi Makaya CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 ACRONYMS 3 FOREWORD 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 2 ELECTORAL SYSTEMS AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 39 CHAPTER 3 POLITICAL PARTIES 71 CHAPTER 4 ELECTORAL LAWS AND MANAGEMENT 89 CHAPTER 5 MAINSTREAM AND SOCIAL MEDIA 111 CHAPTER 6 CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS 131 CHAPTER 7 EFFECTIVE PARTICIPATION 151 ANNEX 1 - Mapping of Gender -

Variable Name

Data codebook for a Round 5 Afrobarometer survey in 34 African countries Prepared by: Chunho Park Michigan State University July 2015 University of Cape Town (UCT) Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) Michigan State University (MSU) Centre for Social Science Research 14 W. Airport Residential Area Department of Political Science Private Bag, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa P.O. Box 404, Legon-Accra, Ghana East Lansing, Michigan 48824 27 21 650 3827•fax: 27 21 650 4657 233 21 776 142•fax: 233 21 763 028 517 353 3377•fax: 517 432 1091 Mattes ([email protected]) Gyimah-Boadi ([email protected]) Bratton ([email protected]) Copyright Afrobarometer Table of Contents Page number Variable descriptives 3-71 Appendix 1: Sample characteristics 72 Appendix 2: List of country abbreviations and country-specific codes 73 Appendix 3: Technical Information Forms for each country survey 74-107 Copyright Afrobarometer 2 Question Number: COUNTRY_ALPHA Question: Country Variable Label: Country in alphabetical order Values: 1-35 Value Labels: 1=Algeria, 2=Benin, 3=Botswana, 4=Burkina Faso, 5=Burundi, 6=Cameroon, 7=Cape Verde, 8=Cote d‟Ivoire, 9=Egypt, 11=Ghana, 12=Guinea, 13=Kenya, 14=Lesotho, 15=Liberia, 16=Madagascar, 17=Malawi, 18=Mali, 19=Mauritius, 20=Morocco, 21=Mozambique, 22=Namibia, 23=Niger, 24=Nigeria, 25=Senegal, 26=Sierra Leone, 27=South Africa, 28=Sudan, 29=Swaziland, 30=Tanzania, 31=Togo, 32=Tunisia, 33=Uganda, 34=Zambia, 35=Zimbabwe Note: Answered by interviewer Question Number: RESPNO Question: Respondent number Variable Label: Respondent -

A SARS-Cov-2 Surveillance System in Sub-Saharan Africa: Modeling Study for Persistence and Transmission to Inform Policy

JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH Post et al Original Paper A SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance System in Sub-Saharan Africa: Modeling Study for Persistence and Transmission to Inform Policy Lori Ann Post1, PhD; Salem T Argaw2, BA; Cameron Jones3, MPH, MD; Charles B Moss4, PhD; Danielle Resnick5, PhD; Lauren Nadya Singh1, MPH; Robert Leo Murphy6, MD; Chad J Achenbach3, MD; Janine White1, MSc; Tariq Ziad Issa2, BA; Michael J Boctor2, BSc; James Francis Oehmke1, PhD 1Buehler Center for Health Policy & Economics and Departments of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States 2Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States 3Division of Infectious Disease, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States 4Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States 5International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, United States 6Institute for Global Health, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States Corresponding Author: Lori Ann Post, PhD Buehler Center for Health Policy & Economics and Departments of Emergency Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine Northwestern University 750 N Lake Shore Dr 9th Floor, Suite 9-9035 Rubloff Building Chicago, IL, 60611 United States Phone: 1 203 980 7107 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Since the novel coronavirus emerged in late 2019, the scientific and public health community around the world have sought to better understand, surveil, treat, and prevent the disease, COVID-19. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), many countries responded aggressively and decisively with lockdown measures and border closures. Such actions may have helped prevent large outbreaks throughout much of the region, though there is substantial variation in caseloads and mortality between nations. -

Population Dynamics and the Demographic Dividend Potential of Eastern and Southern Africa: a Primer

Population Dynamics and the Demographic Dividend Potential of Eastern and Southern Africa: A Primer November 2019 UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office Social Policy Working Paper Population Dynamics and the Demographic Dividend Potential of Eastern and Southern Africa: A Primer © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) United Nations Complex, Gigiri, PO Box 44145 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya November 2019 This is a working document. It has been prepared to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and to stimulate discussion. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF or the United Nations. The text has not been edited to official publication standards, and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this document do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Acknowledgements This working paper was written by Matthew Cummins (Social Policy Regional Adviser, UNICEF ESARO). The author would like to thank Debora Camaione (Public Finance Fellow, UNICEF ESARO) for the outstanding research support and assistance and also for leading the development of the accompanying Africa Population Dynamics Tool. The author is also grateful to the following persons for their comments on earlier drafts: Bo Viktor Nylund (Deputy Regional Director, UNICEF ESARO), Bob Muchabaiwa (Public Finance Specialist, UNICEF ESARO) and Natalie Fol (Regional Adviser Communication for Development, UNICEF ESARO). Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 2. The demographic transition and population boom .............................................................. -

Second Revised Provisional List of Delegations Segunda Lista Provisional Revisada De Delegaciones

X Deuxième liste provisoire révisée des délégations Second revised provisional list of delegations Segunda lista provisional revisada de delegaciones Conférence internationale du Travail 109e session, 2021 International Labour Conference 109th Session, 2021 Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 109.a reunión, 2021 La liste des délégations est présentée sous une forme trilingue. Elle contient d’abord les délégations des Etats Membres de l’Organisation représentées à la Conférence dans l’ordre alphabétique selon le nom en français des Etats. Figurent ensuite les représentants des observateurs, des organisations intergouvernementales et des organisations internationales non gouvernementales invitées à la Conférence. Les noms des pays ou des organisations sont donnés en français, en anglais et en espagnol. Toute autre information (titres et fonctions des participants) est indiquée dans une seule de ces langues, celle choisie par le pays ou l’organisation pour ses communications officielles avec l’OIT. Les noms, titres et qualités figurant dans la liste des délégations correspondent aux indications fournies dans les pouvoirs officiels reçus au mercredi 9 juin 2021, à 16h00. Le délai pour la présentation des protestations concernant les pouvoirs sur la base de cette liste révisée est fixé au vendredi 11 juin à 10h00 (heure de Genève). Toute demande de rectification d'erreurs matérielles (erreurs typographiques, fautes d'orthographe, etc.) pourra être envoyée au secrétariat de la Commission de vérification des pouvoirs ([email protected]) pour qu'il en soit tenu compte dans l'édition révisée de la liste. Toute demande de modification, d'adjonction ou de suppression, etc., concernant les titres, qualités, fonctions ou statut à la Conférence indiqués dans la liste devra être adressée, sous forme de pouvoirs officiels signés par le ministre du Travail, le ministre des Affaires étrangères, le chef de la mission permanente à Genève ou le chef de la délégation du pays intéressé, au secrétariat de la Commission de vérification des pouvoirs.