Dark-Age and Viking-Age Pottery in the Hebrides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anke-Beate Stahl

Anke-Beate Stahl Norse in the Place-nam.es of Barra The Barra group lies off the west coast of Scotland and forms the southernmost extremity of the Outer Hebrides. The islands between Barra Head and the Sound of Barra, hereafter referred to as the Barra group, cover an area approximately 32 km in length and 23 km in width. In addition to Barra and Vatersay, nowadays the only inhabited islands of the group, there stretches to the south a further seven islands, the largest of which are Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay and Bemeray. A number of islands of differing sizes are scattered to the north-east of Barra, and the number of skerries and rocks varies with the tidal level. Barra's physical appearance is dominated by a chain of hills which cuts through the island from north-east to south-west, with the peaks of Heaval, Hartaval and An Sgala Mor all rising above 330 m. These mountains separate the rocky and indented east coast from the machair plains of the west. The chain of hills is continued in the islands south of Barra. Due to strong winter and spring gales the shore is subject to marine erosion, resulting in a ragged coastline with narrow inlets, caves and natural arches. Archaeological finds suggest that farming was established on Barra by 3000 BC, but as there is no linguistic evidence of a pre-Norse place names stratum the Norse immigration during the ninth century provides the earliest onomastic evidence. The Celtic cross-slab of Kilbar with its Norse ornaments and inscription is the first traceable source of any language spoken on Barra: IEptir porgerdu Steinars dottur es kross sja reistr', IAfter Porgero, Steinar's daughter, is this cross erected'(Close Brooks and Stevenson 1982:43). -

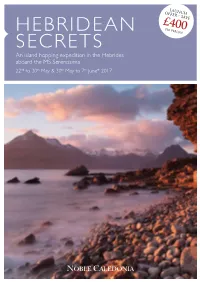

Hebridean Secrets

LAUNCH OFFER - SAVE £400 HEBRIDEAN PER PERSON SECRETS An island hopping expedition in the Hebrides aboard the MS Serenissima 22nd to 30th May & 30th May to 7th June* 2017 St Kilda xxxxxxxx ords do not do justice to the spectacular beauty, rich wildlife and fascinating history of the Inner Wand Outer Hebrides which we will explore during this expedition aboard the MS Serenissima. One of Europe’s last true remaining wilderness areas affords the traveller a marvellous island hopping journey through stunning scenery accompanied by spectacular sunsets and prolific birdlife. With our naturalists and local guides we will explore the length and breadth of the isles, and with our nimble Zodiac craft be able to reach some of the most remote and untouched places. Having arranged hundreds of small ship cruises around Scotland, we have realised that everyone takes something different from the experience. Learn something of the island’s history, see their abundant bird and marine life, but above all revel in the timeless enchantment that these islands exude to all those who appreciate the natural world. We are indeed fortunate in having such marvellous places so close to home. Now, more than ever there is a great appreciation for the peace, beauty and culture of this special corner of the UK. Whether your interest lies in horticulture or the natural world, history or bird watching or simply being there to witness the timeless beauty of the islands, this trip will lift the spirits and gladden the heart. WHAT to EXPECT Flexibility is the key to an expedition cruise. -

Standard Committee Report

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE: 13 JUNE 2007 HEBRIDES ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION PROGRAMME Report by Director for Sustainable Communities PURPOSE OF REPORT: To report progress on implementation of the Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, financial or other constraints to the recommendation being implemented. SUMMARY 2.1 The Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme (HAIP) was initiated to address the need for improved interpretation of archaeological sites in the Western Isles, funded jointly by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and the European Union through the Highlands and Islands Special Transitional Programme. The principal outputs comprise a series of guidebooks, development of websites, and installation of interpretative panels and access improvements at key sites throughout the islands. 2.2 A project officer was appointed, and delivery of the Programme’s objectives, now underway, is due for completion in 2008. Progress towards the stated objectives and targets is monitored by a Steering Group. This report provides a summary of progress. RECOMMENDATION 3.1 It is recommended that the Comhairle note the contents of the progress report on the Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme. Contact Officer: Carol Knott, Archaeological Interpretation Officer (tel. 01851 860679) Background Papers: None REPORT DETAILS BACKGROUND 4.1 Implementation of the Hebrides Archaeological Interpretation Programme began in September 2005. The three principal objectives were progressed concurrently: • Production of a series of three guidebooks to the archaeological sites of the Western Isles, covering Barra; the Uists and Benbecula; and Lewis and Harris. • Development of websites: ‘Archaeology Hebrides’, linked to the ‘Visit Hebrides’ website, aimed at promoting the Western Isles archaeological heritage to prospective visitors; and on-line access to the Western Isles Sites and Monuments Record, a definitive database. -

Roads Revenue Programme 2008/2009 Purpose Of

DMR13108 TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE 16 APRIL 2008 ROADS REVENUE PROGRAMME 2008/2009 PURPOSE OF Report by Director of Technical Services REPORT To propose the Roads Revenue Programme for 2008/2009 for Members’ consideration. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, financial or other constraints to the recommendations being implemented. 1.2 Financial provision is contained within the Comhairle’s Roads Revenue Estimates for the 2008/2009 financial year which allow for the expenditure detailed in this report. SUMMARY 2.1 Members are aware of the continuing maintenance programme undertaken to the roads network throughout the Comhairle’s area on an annual basis with these maintenance works including such items as resurfacing, surface dressing, and general repairs etc. 2.2 The Marshall Block shown in Appendix 1 summarises the proposed revenue expenditure under the various heads for the 2008/2009 financial year and the detailed programme is given in Appendix 2. 2.3 Members are asked to note that because of the unforeseen remedial works that may arise, minor changes may have to be carried out to the programme at departmental level throughout the course of the financial year. 2.4 As Members will be aware the road network has in the last twelve months deteriorated at a greater rate than usual. This is mainly due to the aging bitumen in the surface together with the high number of wet days in the last few months. As a result it is proposed that a proportion of the road surfacing budget be used for “Cut Out Patching.” Due to the rising cost of bitumen products and the stagnant nature of the budget it is not felt appropriate to look at longer sections of surfacing until the damage of the last twelve months has been repaired. -

Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland

Wessex Archaeology Allasdale Dunes, Barra Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 65305 October 2008 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 65305.01 October 2008 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology and Ownership ......................1 1.3 Archaeological Background......................................................................2 Neolithic.......................................................................................................2 Bronze Age ...................................................................................................2 Iron Age........................................................................................................4 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work at Allasdale ............................................5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.................................................................................6 -

The Typological Study of the Structures of the Scottish Brochs Roger Martlew*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 112 (1982), 254-276 The typological study of the structures of the Scottish brochs Roger Martlew* SUMMARY brieA f revie f publishewo d work highlight varyine sth g qualit f informatioyo n available th n eo structural features of brochs, and suggests that the evidence is insufficient to support the current far- reaching theories of broch origins and evolution. The use of numerical data for classification is discussed, and a cluster analysis of broch dimensions is presented. The three groups suggested by this analysis are examined in relation to geographical location, and to duns and 'broch-like' structures in Argyll. While the method is concluded to be useful, an improve- qualit e mendate th th necessar s an f i i t y o improvyo t interpretationd ai resulte o et th d san . INTRODUCTION AND REVIEW OF PUBLISHED WORK The brochs of Scotland have attracted a considerable amount of attention over the years, from the antiquarians of the last century to archaeologists currently working on both rescue and research projects. Modern development principlee th n si techniqued san excavationf so , though, have been applie vero brochsdt w yfe . Severa excavatione th f o lpase decade w th fe tf o s s have indeed been more careful research-orientated projects tha indiscriminate nth e diggin lase th t f go century, when antiquarians seemed intent on clearing out the greatest number of brochs in the shortest possible time. The result, however, is that a considerable amount of material from brochs exists in museum collections, but much of it is from excavations carried out with slight regard for stratigraphy and is consequently of little use in answering the detailed questions set by modern hypotheses. -

Cemeteries of Platform Cairns and Long Cists Around Sinclair's Bay

ProcCEMETERIES Soc Antiq Scot 141OF PLATFORM(2011), 125–143 CAIRNS AND LONG CISTS AROUND SINClair’s BaY, CAITHNESS | 125 Cemeteries of platform cairns and long cists around Sinclair’s Bay, Caithness Anna Ritchie* ABSTRACT The cemetery at Ackergill in Caithness has become the type site for Pictish platform cairns. A re- appraisal based on Society of Antiquaries of Scotland manuscripts, together with published sources, shows that, rather than comprising only the eight cairns and two long cists excavated by Edwards in the 1920s, the cemetery was more extensive. Close to Edwards’ site, Barry had already excavated two other circular cairns, three rectangular cairns and a long cist, and possibly another circular cairn was found between the two campaigns of excavation. Two of the cairns were re-used for subsequent burials, and two cairns were unique in having corbelled chambers built at ground level. Other burial sites along the shore of Sinclair’s Bay are also examined. INTRODUCTION accounts by A J H Edwards of cairns and long cists at Ackergill on Sinclair’s Bay For more than a century after it was founded in Caithness (1926; 1927). These included in 1780, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland square and circular platform cairns of the type was the primary repository in Scotland for that is thought to have been used in Pictish information about sites and artefacts, some times, for which Ackergill remains the type but not all of which were published in the site, and the new information presented here Transactions (Archaeologia Scotica) or in helps both to clarify Ackergill itself and to the Proceedings. -

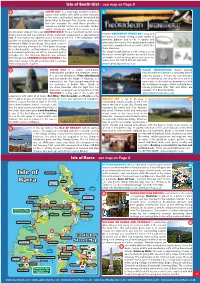

Isle of Barra - See Map on Page 8

Isle of South Uist - see map on Page 8 65 SOUTH UIST is a stunningly beautiful island of 68 crystal clear waters with white powder beaches to the west, and heather uplands dominated by Beinn Mhor to the east. The 20 miles of machair that runs alongside the sand dunes provides a marvellous habitat for the rare corncrake. Golden eagles, red grouse and red deer can be seen on the mountain slopes to the east. LOCHBOISDALE, once a major herring port, is the main settlement and ferry terminal on the island with a population of approximately Visit the HEBRIDEAN JEWELLERY shop and 300. A new marina has opened, and is located at the end of the breakwater with workshop at Iochdar, selling a wide variety of facilities for visiting yachts. Also newly opened Visitor jewellery, giftware and books of quality and Information Offi ce in the village. The island is one of good value for money. This quality hand crafted the last surviving strongholds of the Gaelic language jewellery is manufactured on South Uist in the in Scotland and the crofting industries of peat cutting Outer Hebrides. and seaweed gathering are still an important part of The shop in South Uist has a coffee shop close by everyday life. The Kildonan Museum has artefacts the beach, where light snacks are served. If you from this period. ASKERNISH GOLF COURSE is the are unable to visit our shop, please visit us on our oldest golf course in the Western Isles and is a unique online store. Tel: 01870 610288. HS8 5QX. -

Excavation of an Iron Age, Early Historic and Medieval Settlement and Metalworking Site at Eilean Olabhat, North Uist

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 138 (2008), 27–104 EXCAVATION AT EILEAN OLABHAT, NORTH UIST | 27 Excavation of an Iron Age, Early Historic and medieval settlement and metalworking site at Eilean Olabhat, North Uist Ian Armit*, Ewan Campbell† and Andrew Dunwell‡ with contributions from Rupert Housley, Fraser Hunter, Adam Jackson, Melanie Johnson, Dawn McLaren, Jennifer Miller, K R Murdoch, Jennifer Thoms, and Graeme Warren and illustrations by Alan Braby, Craig Evenden, Libby Mulqueeny and Leeanne Whitelaw ABSTRACT The promontory site of Eilean Olabhat, North Uist was excavated between 1986 and 1990 as part of the Loch Olabhat Research Project. It was shown to be a complex enclosed settlement and industrial site with several distinct episodes of occupation. The earliest remains comprise a small Iron Age building dating to the middle centuries of the first millennium BC , which was modified on several occasions prior to its abandonment. Much later, the Early Historic remains comprise a small cellular building, latterly used as a small workshop within which fine bronze and silverwork was produced in the fifth to seventh centuries AD . Evidence of this activity is represented by quantities of mould and crucible fragments as well as tuyère and other industrial waste products. The site subsequently fell into decay for a second time prior to its medieval reoccupation probably in the 14th to 16th centuries AD . Eilean Olabhat has produced a well-stratified, though discontinuous, structural and artefactual sequence from the mid-first millennium BC to the later second millennium AD , and has important implications for ceramic development in the Western Isles over that period, as well as providing significant evidence for the nature and social context of Early Historic metalworking. -

Iron Age Scotland: Scarf Panel Report

Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Images ©as noted in the text ScARF Summary Iron Age Panel Document September 2012 Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Summary Iron Age Panel Report Fraser Hunter & Martin Carruthers (editors) With panel member contributions from Derek Alexander, Dave Cowley, Julia Cussans, Mairi Davies, Andrew Dunwell, Martin Goldberg, Strat Halliday, and Tessa Poller For contributions, images, feedback, critical comment and participation at workshops: Ian Armit, Julie Bond, David Breeze, Lindsey Büster, Ewan Campbell, Graeme Cavers, Anne Clarke, David Clarke, Murray Cook, Gemma Cruickshanks, John Cruse, Steve Dockrill, Jane Downes, Noel Fojut, Simon Gilmour, Dawn Gooney, Mark Hall, Dennis Harding, John Lawson, Stephanie Leith, Euan MacKie, Rod McCullagh, Dawn McLaren, Ann MacSween, Roger Mercer, Paul Murtagh, Brendan O’Connor, Rachel Pope, Rachel Reader, Tanja Romankiewicz, Daniel Sahlen, Niall Sharples, Gary Stratton, Richard Tipping, and Val Turner ii Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Executive Summary Why research Iron Age Scotland? The Scottish Iron Age provides rich data of international quality to link into broader, European-wide research questions, such as that from wetlands and the well-preserved and deeply-stratified settlement sites of the Atlantic zone, from crannog sites and from burnt-down buildings. The nature of domestic architecture, the movement of people and resources, the spread of ideas and the impact of Rome are examples of topics that can be explored using Scottish evidence. The period is therefore important for understanding later prehistoric society, both in Scotland and across Europe. There is a long tradition of research on which to build, stretching back to antiquarian work, which represents a considerable archival resource. -

The Utilisation of Fur-Bearing Animals in the British Isles a Zooarchaeological Hunt for Data

The utilisation of fur-bearing animals in the British Isles A zooarchaeological hunt for data E.H. Fairnell MSc in Zooarchaeology The University of York Department of Archaeology (Incorporating the former Institute for Advanced Architectural Studies) September 2003 ‘There was nothing Lucy liked so much as the smell and feel of fur’ … C.S. Lewis (1953) The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Abstract E.H. Fairnell The utilisation of fur-bearing animals in the British Isles: a zooarchaeological hunt for data MSC in Zooarchaeology viii prelims + 126pp (including 9 tables, 53 figures and 57 maps) + an appendix of 63pp + CD-ROM Few studies of the use of animals for their fur seem to be based on analysis of the remains of the species themselves. A database of zooarchaeological records of fur-bearing species was compiled from a systematic literature search. The species considered were bear, badger, beaver, cat, dog, ferret, fox, hare, pine marten, polecat, otter, rabbit, seal, squirrel, stoat and weasel. Preliminary analyses of data for England and Scotland seem to suggest a consistent use of fairly local resources to meet practical and fashionable demands. A few records from the 10th–17th centuries may show bulk processing of pelts, but they could be self- sufficient measures to save costs within the context of an expensive fur trade. Contents List of tables v List of figures vi List of maps vii Appendix and CD-ROM particulars viii 1 Introduction 1 The background 1 The present study 6 2 The role of zooarchaeology in identifying evidence of utilising -

1966 REPORT of the SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN SOCIETY (Founded in 1960) Proprietor the SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN COMPANY LIMITED (Registered As a Charity} Directors of the Company A

www.schools-hebridean-society.co.uk THE 1966 REPORT OF THE SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN SOCIETY (Founded in 1960) Proprietor THE SCHOOLS HEBRIDEAN COMPANY LIMITED (Registered as a Charity} Directors of the Company A. J. ABBOTT. B.A. (Chairman) R. M. FOUNTAINS, B.A. A. S. BATEMAN, B.A. M. J. UNDERBILL, M.A., A. J. C BRADSHAW, B.A. Grad.I.E.R.E. C. M. CHILD, B.A. D. T. VIGAR C. J. DAWSON. B.A. T. J. WILLCOCKS. B.A.I. C. D. FOUNTAINE Hon. Advisers to the Society THE LORD BISHOP OF NORWICH G. L. DAVIES, ESQ.. M.A., Trinity College. Dublin S. L. HAMILTON, ESQ., M.B.E., Inverness I. SUTHERLAND. ESQ., M.A. Headmaster of St. John's School, Leatherhead CONTENTS Page Map of Scotland and (he Isles Foreword by J. S. Grant, M.A.. O.B.E 2 Editorial Comment 3 De Navibus 3 Lewis Expedition 1966 4 Harris Expedition 1966 24 Book Review 34 Jura Expedition 1966 35 Colonsay Expedition 1966 42 Dingle Expedition 1966 53 Ornithological Summary 1966 56 Plans for 1967 61 Acknowledgements 61 Expedition Members .. 62 S.H.S. Tie order form 72 The Editor of the Report is C. J. Dawson FOREWORD EDITORIAL COMMENT By J. S. Grant, Esq., M.A., O.B.E., As 1 have discovered, it is by no means easy to maintain the high Chairman of the Crofters Commission standard set by Martin Child, who built this publication up from nothing to what it is now. Fortunately he has not left the scene I sometimes think.