Resource: Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Reform Measure

GS 2027 Legislative Reform Measure CONTENTS Legislative burdens 1Power to remove or reduce burdens 2 Preconditions 3Exceptions 4 Consultation 5 Laying proposals before the General Synod 6 Scrutiny and amendment Consolidation 7 Pre-consolidation amendments General and final provisions 8Orders 9 Short title, commencement and extent First Consideration July 2016 Legislative Reform Measure 1 DRAFT of a Measure to enable provision to be made for the purpose of removing or reducing burdens resulting from ecclesiastical legislation; and to enable provision to be made for the purpose of facilitating consolidations of ecclesiastical legislation. Legislative burdens 1 Power to remove or reduce burdens (1) The Archbishops’ Council may by order make provision which it considers would remove or reduce a burden, or the overall burdens, resulting directly or indirectly for any person from ecclesiastical legislation. 5 (2) “Burden” means— (a) a financial cost, (b) an administrative inconvenience, or (c) an obstacle to efficiency. (3) “Ecclesiastical legislation” means any of the following or a provision of any of 10 them— (a) a Measure of the General Synod (whether passed before or after the commencement of this section); (b) a Measure of the Church Assembly; (c) a public general Act or local Act in so far as it relates to matters 15 concerning the Church of England (whether passed before or after the commencement of this section); (d) any Order in Council, order, rules, regulations, directions, scheme or other subordinate instrument made under a provision of— (i) a Measure or Act referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c), or 20 (ii) a subordinate instrument itself made under a provision of a Measure or Act referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c). -

Cornishness and Englishness: Nested Identities Or Incompatible Ideologies?

CORNISHNESS AND ENGLISHNESS: NESTED IDENTITIES OR INCOMPATIBLE IDEOLOGIES? Bernard Deacon (International Journal of Regional and Local History 5.2 (2009), pp.9-29) In 2007 I suggested in the pages of this journal that the history of English regional identities may prove to be ‘in practice elusive and insubstantial’.1 Not long after those words were written a history of the north east of England was published by its Centre for Regional History. Pursuing the question of whether the north east was a coherent and self-conscious region over the longue durée, the editors found a ‘very fragile history of an incoherent and barely self-conscious region’ with a sense of regional identity that only really appeared in the second half of the twentieth century.2 If the north east, widely regarded as the most coherent English region, lacks a historical identity then it is likely to be even more illusory in other regions. Although rigorously testing the past existence of a regional discourse and finding it wanting, Green and Pollard’s book also reminds us that history is not just about scientific accounts of the past. They recognise that history itself is ‘an important element in the construction of the region … Memory of the past is deployed, selectively and creatively, as one means of imagining it … We choose the history we want, to show the kind of region we want to be’.3 In the north east that choice has seemingly crystallised around a narrative of industrialization focused on the coalfield and the gradual imposition of a Tyneside hegemony over the centuries following 1650. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Chris Dunkerley\My Documents\Excel

CORNISH ASSOCIATION OF NSW - MEMBERS LENDING & RESEARCH LIBRARY - Jan 2008 Search using Edit, Find in this page (Firefox) For more information or to borrow contact Eddie or Eileen Lyon on: (02) 9349 1491 or Email: [email protected] Id No BOOK NAME AUTHOR DESCRIPTION 1 Yesterday's Town: St Ives Noall Cyril Book - illustrated history 2 King Arthur Country in Cornwall Duxbury & Williams Book - information 3 Story of St Ives, The Noall Cyril Book 4 St Ives in the 1800's Laity R.P. Book 5 Cornish Surnames, A Handbook of G. Pawley White Book 6 Cornish Pioneers of Ballarat Dell & Menhennet Book 7 Kernewek for Kids Franklin Sharon Book - Copper Triangle Puzzles, Stories 8 Australian Celtic Journal Vol.One Darlington J Journal 9 Microform Collection Index (OUT OF CIRCULATION) Aust. Soc of Genealogy Journal 10 Where Now Cousin Jack? Hopkins Ruth Book 11 Cornwall - A Genealogical Bibliography Raymond Stuart Journal LOST 12 Penwith - The Illustrated Past Noall Cyril Book 13 St Ives, The Book of Noall Cyril Book - pictorial history LOST IN FIRE 14 Cornish Names Dexter T.F.G. Book 15 Scilly and the Scillonians Read A.H. & Son Book - pictorial history 16 Shipwrecks at Land's End Larn & Mills Book 17 Minerals, Rocks and Gemstones in Cornwall Rogers Cedric Book - collector’s guide 18 King Arthur, Tintagel Castle & Celtic Monuments Tintagel Parish Council Book 19 Shipwrecks on the Isles of Scilly Gibson F.E. Book 20 Which Francis Symonds Symonds John Symonds history - Cornwall and Australia 21 St Ives, The Beauty of Badger H.G. Illustration Booklet 22 Little Land of Cornwall, The Rowse A.L. -

Law, Counsel, and Commonwealth: Languages of Power in the Early English Reformation

Law, Counsel, and Commonwealth: Languages of Power in the Early English Reformation Christine M. Knaack Doctor of Philosophy University of York History April 2015 2 Abstract This thesis examines how power was re-articulated in light of the royal supremacy during the early stages of the English Reformation. It argues that key words and concepts, particularly those involving law, counsel, and commonwealth, formed the basis of political participation during this period. These concepts were invoked with the aim of influencing the king or his ministers, of drawing attention to problems the kingdom faced, or of expressing a political ideal. This thesis demonstrates that these languages of power were present in a wide variety of contexts, appearing not only in official documents such as laws and royal proclamations, but also in manuscript texts, printed books, sermons, complaints, and other texts directed at king and counsellors alike. The prose dialogue and the medium of translation were employed in order to express political concerns. This thesis shows that political languages were available to a much wider range of participants than has been previously acknowledged. Part One focuses on the period c. 1528-36, investigating the role of languages of power during the period encompassing the Reformation Parliament. The legislation passed during this Parliament re-articulated notions of the realm’s social order, creating a body politic that encompassed temporal and spiritual members of the realm alike and positioning the king as the head of that body. Writers and theorists examined legal changes by invoking the commonwealth, describing the social hierarchy as an organic body politic, and using the theme of counsel to acknowledge the king’s imperial authority. -

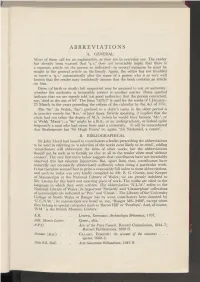

ABBREVIATIONS Use. the Reader That

ABBREVIATIONS A. GENERAL Most of these call for no explanation, as they are in everyday use. The reader has already been warned that 'q.v.' does not invariably imply that there is a separate article on the person so indicated—in several instances he must be sought in the general article on his family. Again, the editor has not troubled to insert a 'q.v.' automatically after the name of a person who is so very well known that the reader may confidently assume that the book contains an article on him. Dates (of birth or death) left unqueried may be assumed to rest on authority: whether the authority is invariably correct is another matter. Dates queried indicate that we are merely told (on good authority) that the person concerned, say, 'died at the age of 64'. The form '1676/7' is used for the weeks of 1 January- 25 March in the years preceding the reform of the calendar by the Act of 1751. The 'Sir' (in Welsh, 'Syr') prefixed to a cleric's name in the older period is in practice merely the 'Rev.' of later times. Strictly speaking, it implied that the cleric had not taken the degree of M.A. (when he would have become 'Mr.', or in Welsh 'Mastr'); a 'Sir' might be a B.A., or an undergraduate, or indeed quite frequently a man who had never been near a university. It will be remembered that Shakespeare has 'Sir Hugh Evans' or, again, 'Sir Nathaniel, a curate'. B. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL Sir John Lloyd had issued to contributors a leaflet prescribing the abbreviations to be used in referring to 'a selection of the works most likely to be cited', adding 'contributors will abbreviate the titles of other works, but the abbreviations should not be such as to furnish no clue at all to the reader when read without context'. -

Form Foreign Policy Took- Somerset and His Aims: Powers Change? Sought to Continue War with Scotland, in Hope of a Marriage Between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots

Themes: How did relations with foreign Form foreign policy took- Somerset and his aims: powers change? Sought to continue war with Scotland, in hope of a marriage between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots. Charles V up to 1551: The campaign against the Scots had been conducted by Somerset from 1544. Charles V unchallenged position in The ‘auld alliance’ between Franc and Scotland remained, and English fears would continue to be west since death of Francis I in dominated by the prospect of facing war on two fronts. 1547. Somerset defeated Scots at Battle of Pinkie in September 1547. Too expensive to garrison 25 border Charles won victory against forts (£200,000 a year) and failed to prevent French from relieving Edinburgh with 10,000 troops. Protestant princes of Germany at In July 1548, the French took Mary to France and married her to French heir. Battle of Muhlberg, 1547. 1549- England threatened with a French invasion. France declares war on England. August- French Ottomans turned attention to attacked Boulogne. attacking Persia. 1549- ratified the Anglo-Imperial alliance with Charles V, which was a show of friendship. Charles V from 1551-1555: October 1549- Somerset fell from power. In the west, Henry II captured Imperial towns of Metz, Toul and Verdun and attacked Charles in the Form foreign policy-Northumberland and his aims: Netherlands. 1550- negotiated a settlement with French. Treaty of In Central Europe, German princes Somerset and Boulogne. Ended war, Boulogne returned in exchange for had allied with Henry II and drove Northumberland 400,000 crowns. England pulled troops out of Scotland. -

The Western Rebellion of 1549 Religious Protest in Devon and Cornwall

Mark Stoyle The Western Rebellion of 1549 Religious protest in Devon and Cornwall What was the Tudor rebellion in Devon and Cornwall all about? Where did it begin? How did it spread? How was it eventually put down? Yet while the king had changed the religious Exam links landscape of England forever, he had remained firmly opposed to the new strain of Christianity which was AQA 1C The Tudors: England, 1485–1603 then taking root across large parts of the continent, Edexcel paper 3, option 31 Rebellion and disorder and which would eventually become known as under the Tudors, 1485–1603 Protestantism. As a result, religious traditionalists OCR Y136/Y106 England 1485–1558: the early Tudors — who almost certainly made up the great majority OCR Y306 Rebellion and disorder under the of Henry’s subjects — had generally managed to Tudors, 1485–1603 adapt themselves to the old king’s unsettling policies. Following Henry’s death in 1547, however, and the accession to the throne of his 9-year-old son, uring the summer of 1549, a huge popular Edward VI, England witnessed a full-blown religious rebellion took place in Devon and Cornwall. revolution. DThousands of people took part in the insurrection and the government of Edward VI was Edward VI and religious revolution eventually forced to raise a powerful army in order Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, was appointed as to suppress it. Lord Protector and therefore effectively ruled England in the boy-king’s name. Seymour soon made it clear Background to the rebellion that Edward’s government was determined to steer The Western Rebellion had many contributory causes, the English Church in an unambiguously Protestant but it was basically a protest against religious change. -

The Northern Clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Altazin, Keith, "The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 543. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NORTHERN CLERGY AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Keith Altazin B.S., Louisiana State University, 1978 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2003 August 2011 Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation would have not been possible without the support, assistance, and encouragement of a number of people. First, I would like to thank the members of my doctoral committee who offered me great encouragement and support throughout the six years I spent in the graduate program. I would especially like thank Dr. Victor Stater for his support throughout my journey in the PhD program at LSU. From the moment I approached him with my ideas on the Pilgrimage of Grace, he has offered extremely helpful advice and constructive criticism. -

Britishness, What It Is and What It Could Be, Is

COUNTY, NATION, ETHNIC GROUP? THE SHAPING OF THE CORNISH IDENTITY Bernard Deacon If English regionalism is the dog that never barked then English regional history has in recent years been barely able to raise much more than a whimper.1 Regional history in Britain enjoyed its heyday between the late 1970s and late1990s but now looks increasingly threadbare when contrasted with the work of regional geographers. Like geographers, in earlier times regional historians busied themselves with two activities. First, they set out to describe social processes and structures at a regional level. The region, it was claimed, was the most convenient container for studying ‘patterns of historical development across large tracts of the English countryside’ and understanding the interconnections between social, economic, political, demographic and administrative history, enabling the researcher to transcend both the hyper-specialization of ‘national’ historical studies and the parochial and inward-looking gaze of English local history.2 Second, and occurring in parallel, was a search for the best boundaries within which to pursue this multi-disciplinary quest. Although he explicitly rejected the concept of region on the grounds that it was impossible comprehensively to define the term, in many ways the work of Charles Phythian-Adams was the culmination of this process of categorization. Phythian-Adams proposed a series of cultural provinces, supra-county entities based on watersheds and river basins, as broad containers for human activity in the early modern period. Within these, ‘local societies’ linked together communities or localities via networks of kinship and lineage. 3 But regions are not just convenient containers for academic analysis. -

Amarc-Newsletter-69-October-2017

3 4B 4BNewsletter no. 69 October 2017 Newsletter of the Association for Manuscripts and Archives in Research Collections www.amarc.org.uk STATE AND CITY LIBRARY OF AUGSBURG CELEBRATE 480TH ANNIVERSAIRY State and City Library of Augsburg, Cim 66, ff.5v-6r The arms of the ancestors of Philipp Hainhofer and Regina Waiblinger on a peacock’s fan, miniature from Philipp Hainhofer’s Stammens-Beschreibung, Augsburg, 1626. © By kind permission of the State and City Library of Augsburg. After ten years as the Editor, Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan has handed over responsibility for the AMARC Newsletter to Becky Lawton at the British Library, assisted by Rachael Merrison, archivist at Cheltenham College. The Chairman and committee of AMARC are deeply appreciative of Ceridwen’s labours and of the high quality of the Newsletter and trust that we shall continue to see her at meetings. ISSN 1750-9874 AMARC Newsletter no. 69 October 2017 A unique example of 15th century printed text by English printer William Caxton, discovered in University of Reading Special Collections © By kind permission of the University of Reading Special Collections CONTENTS AMARC matters 2 Grants & Scholarships 16 AMARC meetings 5 Courses 18 Personal 6 Exhibitions 20 MSS News 6 New Accessions 25 Projects 10 Book reviews 29 Lectures 12 New Publications 33 Conferences & Call for 12 Websites 34 Papers AMARC Membership Secretary, AMARC MEMBERSHIP Archivist, The National Gallery Membership can be personal or in- stitutional. Institutional members Trafalgar Square, London, WC2N receive two copies of mailings, 5DN; email: Richard.Wragg@ng- have triple voting rights, and may london.org.uk. -

Fictions of Collaboration : Authors and Editors in the Sixteenth Century

Fictions of collaboration : authors and editors in the sixteenth century Autor(en): Burrow, Colin Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: SPELL : Swiss papers in English language and literature Band (Jahr): 25 (2011) PDF erstellt am: 10.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-389636 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Fictions of Collaboration: Authors and Editors in the Sixteenth Century CoUn Burrow This essay tracks the changing relationship between authors and editors (or print-shop "overseers" of kterary texts), in the second half of the sixteenth century. Beginning with the pubücation of works by Thomas More, Thomas Wyatt, and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, it shows how editorial activity helped to fashion the ways in which authors were represented. -

Whoso List to Hunt by Sir Thomas Wyatt 1503

Whoso List to Hunt Whoever Loves to Hunt By Sir Thomas Wyatt 1503-1542 Modernized by Michael R. Burch Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind, Whoever loves to hunt, I know the hind; But as for me, hélas, I may no more. but as for me, alas!, I may no more. The vain travail hath wearied me so sore, Pursuit of her has left me so bone-sore, I am of them that farthest cometh behind. I'm one of those who lags the furthest behind. Yet may I by no means my wearied mind Yet friend, how can I draw my anguished mind Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore away from the deer? Thus, as she flees before Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore, me, fainting I follow. I must leave off therefore, Sithens in a net I seek to hold the wind. since in a net I seek to hold the wind. Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt, Whoever seeks her out, I put him out of doubt, As well as I may spend his time in vain. that like me, he must spend his time in vain. And graven with diamonds in letters plain For graven with diamonds, set in letters plain, There is written, her fair neck round about: these words appear, her fair neck ringed about: Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am, Touch me not, for Caesar's I am, And wild for to hold, though I seem tame. And wild to hold, though I seem tame.