Daniel J. Hill Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

Legislative Reform Measure

GS 2027 Legislative Reform Measure CONTENTS Legislative burdens 1Power to remove or reduce burdens 2 Preconditions 3Exceptions 4 Consultation 5 Laying proposals before the General Synod 6 Scrutiny and amendment Consolidation 7 Pre-consolidation amendments General and final provisions 8Orders 9 Short title, commencement and extent First Consideration July 2016 Legislative Reform Measure 1 DRAFT of a Measure to enable provision to be made for the purpose of removing or reducing burdens resulting from ecclesiastical legislation; and to enable provision to be made for the purpose of facilitating consolidations of ecclesiastical legislation. Legislative burdens 1 Power to remove or reduce burdens (1) The Archbishops’ Council may by order make provision which it considers would remove or reduce a burden, or the overall burdens, resulting directly or indirectly for any person from ecclesiastical legislation. 5 (2) “Burden” means— (a) a financial cost, (b) an administrative inconvenience, or (c) an obstacle to efficiency. (3) “Ecclesiastical legislation” means any of the following or a provision of any of 10 them— (a) a Measure of the General Synod (whether passed before or after the commencement of this section); (b) a Measure of the Church Assembly; (c) a public general Act or local Act in so far as it relates to matters 15 concerning the Church of England (whether passed before or after the commencement of this section); (d) any Order in Council, order, rules, regulations, directions, scheme or other subordinate instrument made under a provision of— (i) a Measure or Act referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c), or 20 (ii) a subordinate instrument itself made under a provision of a Measure or Act referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c). -

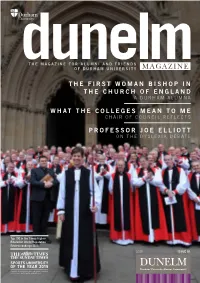

ISSUE 01 the New Alumni Community Website

THE MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF DURHAM UNIVERSITY THE FIRST WOMAN BISHOP IN THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND A DURHAM ALUMNA WHAT THE COLLEGES MEAN TO ME CHAIR OF COUNCIL REFLECTS PROFESSOR JOE ELLIOTT ON THE DYSLEXIA DEBATE Top 100 in the Times Higher Education World Reputation Review rankings 2015 2015 ISSUE 01 www.dunelm.org.uk The new alumni community website We’ll be continuing development of the website over the coming months, so do let us know what you think and what you’d like to see there. The alumni community offers useful connections all over the world, with a global events calendar backed by a network of alumni volunteers and associations, combining professional networking and social gatherings with industry-specific workshops and research dissemination. We have major events in cities across the UK and around the world, ranging from formal dinners, grand balls, exclusive receptions and wine tastings, to Christmas carol concerts, sporting events, family days and more. Ads.indd 2 19/03/2015 13:58 ISSUE 01 2015 DUNELM MAGAZINE 3 www.dunelm.org.uk The new alumni community website Welcome to your new alumni magazine. It is particularly gratifying to find a new way to represent the Durham experience. Since I joined the University two and a half years ago, I have been amazed by how multi-faceted it all is. I therefore hope that the new version of this magazine is able to reflect that richness in the same way that Durham First did for so many years. In fact, in order to continue to offer exceptional communication, we have updated your alumni magazine, your website - www.dunelm.org.uk - and your various social media pages. -

January 2015

Our Church is eco-friendly Bishop Allan Scarfe on 2014 Annual Youth Conference “The earth is the Lord’S, and the from page 6….as part of our time there, as well as participate in the Youth Conference. We are fullness thereof: the world, and they grateful too for the care of the people at Thokoza that dwell therein”. and for the friendships we have made, especially net Psalm 24:1 dJanuaryio 2015 issue15 Vol 2 with our translators and drivers. We bring home a new song in our hearts quite literally, as a Seswati song you taught us has ANGLICAN CHURCH DIOCESE OF SWAZILAND NEWS LETTER been turned into an English song of praise by our talented musician. Some of us are pondering “We aspire to be a caring church that empowers people for potential vocations which we heard from God as we were with you. The Dioceses are working on ABUNDANT LIFE” Youth from Iowa and Brechin rendering a song during the 2014 annual youth confer- ence at St Michaels Chapel. Reflection from The Dean new projects and plans to deepen our work together and we are entrusting the future to God and to your I greet you in the name of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. I write hands and hearts together now that the introductions have been made. Thank you, dear people of Swazi- to you just before we begin Lent and in one of the past important land. You are God‘s instruments of encouragement and spiritual renewal for us all. days we remembered a host of important Saints. -

Law, Counsel, and Commonwealth: Languages of Power in the Early English Reformation

Law, Counsel, and Commonwealth: Languages of Power in the Early English Reformation Christine M. Knaack Doctor of Philosophy University of York History April 2015 2 Abstract This thesis examines how power was re-articulated in light of the royal supremacy during the early stages of the English Reformation. It argues that key words and concepts, particularly those involving law, counsel, and commonwealth, formed the basis of political participation during this period. These concepts were invoked with the aim of influencing the king or his ministers, of drawing attention to problems the kingdom faced, or of expressing a political ideal. This thesis demonstrates that these languages of power were present in a wide variety of contexts, appearing not only in official documents such as laws and royal proclamations, but also in manuscript texts, printed books, sermons, complaints, and other texts directed at king and counsellors alike. The prose dialogue and the medium of translation were employed in order to express political concerns. This thesis shows that political languages were available to a much wider range of participants than has been previously acknowledged. Part One focuses on the period c. 1528-36, investigating the role of languages of power during the period encompassing the Reformation Parliament. The legislation passed during this Parliament re-articulated notions of the realm’s social order, creating a body politic that encompassed temporal and spiritual members of the realm alike and positioning the king as the head of that body. Writers and theorists examined legal changes by invoking the commonwealth, describing the social hierarchy as an organic body politic, and using the theme of counsel to acknowledge the king’s imperial authority. -

The Northern Clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Altazin, Keith, "The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 543. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NORTHERN CLERGY AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Keith Altazin B.S., Louisiana State University, 1978 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2003 August 2011 Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation would have not been possible without the support, assistance, and encouragement of a number of people. First, I would like to thank the members of my doctoral committee who offered me great encouragement and support throughout the six years I spent in the graduate program. I would especially like thank Dr. Victor Stater for his support throughout my journey in the PhD program at LSU. From the moment I approached him with my ideas on the Pilgrimage of Grace, he has offered extremely helpful advice and constructive criticism. -

Dean of Derby Briefing Pack

Dean of Derby Candidate Briefing Pack October 2019 CONTENTS Foreword from the Bishop of Derby .................................................................................................... 3 Dean of Derby Role Profile ..................................................................................................................... 4 Context ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Additional Information............................................................................................................................ 11 Foreword from the Bishop of Derby I am hoping to appoint a Dean with imagination, drive and energy to lead the Cathedral forward in its mission and ministry as we enter a new decade, and a new phase of life across the diocese. The next Dean of Derby will be committed to the nurture of the Cathedral community in faith, witness and service, growing its current congregations, and discovering ways to reach new and more diverse people. The Dean will continue to be creative about growing the influence and reach of the cathedral as a key partner in the city and region. They will be able to oversee the development of buildings to be fit for purpose and lead the strengthening of the Cathedral’s financial and governance resilience. I am aware that the Cathedral requires stability and continuity (the number of Deans in the past decade or so leaves the Cathedral feeling somewhat vulnerable) but partnered with creativity and challenge. There is much that is good and strong, and the potential is considerable. The Diocese of Derby, too, is in transition, facing considerable challenge and exciting opportunity. The Dean will be a partner in that wider vision setting and strategic planning for the whole diocese. The new Dean, therefore, will have a wide perspective and a long view, and be able to expand horizons and raise expectations for the Cathedral, city and diocese. -

Apostolicae Curae Catholic.Net

Apostolicae Curae Catholic.net On the Nullity of Anglican Orders Apostolicae Curae Promulgated September 18, 1896 by Pope Leo XIII In Perpetual Remembrance 1. We have dedicated to the welfare of the noble English nation no small portion of the Apostolic care and charity by which, helped by His grace, we endeavor to fulfill the office and follow in the footsteps of "the Great Pastor of the sheep," Our Lord Jesus Christ. The letter which last year we sent to the English seeking the Kingdom of Christ in the unity of the faith is a special witness of our good will towards England. In it we recalled the memory of the ancient union of the people with Mother Church, and we strove to hasten the day of a happy reconciliation by stirring up men's hearts to offer diligent prayer to God. And, again, more recently, when it seemed good to Us to treat more fully the unity of the Church in a General Letter, England had not the last place in our mind, in the hope that our teaching might both strengthen Catholics and bring the saving light to those divided from us. It is pleasing to acknowledge the generous way in which our zeal and plainness of speech, inspired by no mere human motives, have met the approval of the English people, and this testifies not less to their courtesy than to the solicitude of many for their eternal salvation. 2. With the same mind and intention, we have now determined to turn our consideration to a matter of no less importance, which is closely connected with the same subject and with our desires. -

CNI December 18

CNI December 18 Christian Brothers' Grammar sticking to selection York Minster to host historic consecration of England's first woman bishop Archbishop Justin Welby welcomed the announcement of the Revd Libby Lane, currently Vicar of St Peter's, Hale, York Minster to host historic consecration of England's first and St Elizabeth's, woman bishop Ashley, as the new Bishop of Stockport. The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Revd Justin Welby, said: “I am absolutely delighted that Libby has been appointed to succeed Bishop Robert Atwell as Bishop of Stockport. Her Christ-centred life, calmness and clear determination to serve the church and the community make her a wonderful choice. “She will be bishop in a diocese that has been outstanding in its development of people, and she will make a major contribution. She and her family will be in my prayers during the initial excitement, and the pressures of moving." Page 1 CNI December 18 The Church of England's first woman bishop will be consecrated in a historic service at York Minster next month. Rev Lane was ordained as a priest in 1994 and has served a number of parish and chaplaincy roles in the North of England, including in the Diocese of York The Revd Libby Lane. from 1996 to 1999. The Archbishop of York, Dr John Sentamu, said yesterday: "It is with great joy that on January 26, 2015 - the feast of Timothy and Titus, companions of Paul - I will be in York Minster, presiding over the consecration of the Revd Libby Lane as Bishop Suffragan of Stockport. -

Legislative Reform Measure 2018

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally enacted). Legislative Reform Measure 2018 2018 No. 5 A Measure passed by the General Synod of the Church of England to enable provision to be made for the purpose of removing or reducing burdens resulting from ecclesiastical legislation; and to enable provision to be made for the purpose of facilitating consolidations of ecclesiastical legislation. [10th May 2018] Legislative burdens 1 Power to remove or reduce burdens (1) The Archbishops’ Council may by order make provision which it considers would remove or reduce a burden, or the overall burdens, resulting directly or indirectly for any person from ecclesiastical legislation. (2) “Burden” means— (a) a financial cost, (b) an administrative inconvenience, or (c) an obstacle to efficiency. (3) “Ecclesiastical legislation” means any of the following or a provision of any of them— (a) a Measure of the General Synod (whether passed before or after the commencement of this section); (b) a Measure of the Church Assembly; (c) a public general Act or local Act in so far as it forms part of the ecclesiastical law of the Church of England (whether passed before or after the commencement of this section); (d) an Order in Council, order, rules, regulations, directions, scheme or other subordinate instrument made under a provision of— (i) a Measure or Act referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c), or (ii) a subordinate instrument itself made under a provision of a Measure or Act referred to in paragraph (a), (b) or (c). 2 Legislative Reform Measure 2018 (c. 5) Document Generated: 2018-08-07 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally enacted). -

Pdf (Accessed January 21, 2011)

Notes Introduction 1. Moon, a Presbyterian from North Korea, founded the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity in Korea on May 1, 1954. 2. Benedict XVI, post- synodal apostolic exhortation Saramen- tum Caritatis (February 22, 2007), http://www.vatican.va/holy _father/benedict_xvi/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi _exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis_en.html (accessed January 26, 2011). 3. Patrician Friesen, Rose Hudson, and Elsie McGrath were subjects of a formal decree of excommunication by Archbishop Burke, now a Cardinal Prefect of the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signa- tura (the Roman Catholic Church’s Supreme Court). Burke left St. Louis nearly immediately following his actions. See St. Louis Review, “Declaration of Excommunication of Patricia Friesen, Rose Hud- son, and Elsie McGrath,” March 12, 2008, http://stlouisreview .com/article/2008-03-12/declaration-0 (accessed February 8, 2011). Part I 1. S. L. Hansen, “Vatican Affirms Excommunication of Call to Action Members in Lincoln,” Catholic News Service (December 8, 2006), http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/0606995.htm (accessed November 2, 2010). 2. Weakland had previously served in Rome as fifth Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Confederation (1967– 1977) and is now retired. See Rembert G. Weakland, A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop (Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans, 2009). 3. Facts are from Bruskewitz’s curriculum vitae at http://www .dioceseoflincoln.org/Archives/about_curriculum-vitae.aspx (accessed February 10, 2011). 138 Notes to pages 4– 6 4. The office is now called Vicar General. 5. His principal consecrator was the late Daniel E. Sheehan, then Arch- bishop of Omaha; his co- consecrators were the late Leo J. -

DISPENSATION and ECONOMY in the Law Governing the Church Of

DISPENSATION AND ECONOMY in the law governing the Church of England William Adam Dissertation submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Wales Cardiff Law School 2009 UMI Number: U585252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585252 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................................................................................................................VI ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................................................................VII TABLE OF STATUTES AND MEASURES............................................................................................ VIII U K A c t s o f P a r l i a m e n