Baker.Weber.Njefficiency 8 2 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 High Schools.Pdf

2019 National Blue Ribbon Schools High Schools Arizona The Charter School of Wilmington Arizona College Prep Erie Campus 100 North Dupont Road 1150 West Erie Street Wilmington, DE 19807‐3199 Chandler , AZ 85224‐4316 Phone: (302) 651‐2727 Phone: (480) 424‐8000 District: The Charter School of Wilmington District: Chandler Unified School Department of Defense California AFNorth Middle/High School Lowell Alternative High School Unit 21606 APO 1101 Eucalyptus Dr Netherlands, DD 09703‐1601 San Francisco, CA 94132‐1401 Phone: (314) 366‐6941 Phone: (415) 759‐2730 District: Europe ‐ West District: San Francisco Unified School Vicenza High School Oxford Academy Unit 31401, Box 11 5172 Orange Avenue Vicenza, Italy, DD 09630‐0005 Cypress, CA 90630‐2921 Phone: (044) 461‐8600 Phone: (714) 220‐3055 District: Europe ‐ South District: Anaheim Union High School Florida Connecticut Atlantic Technical College and Technical High Guilford High School School 605 New England Road 4700 Coconut Creek Parkway Guilford, CT 06437‐1838 Coconut Creek, FL 33063‐3967 Phone: (203) 453‐2741 Phone: (754) 321‐5100 District: Guilford Public Schools District: Broward Delaware Florida SouthWestern Collegiate High School Delaware Military Academy 26300 Airport Road 112 Middleboro Road Punta Gorda, FL 33950‐5748 Wilmington, DE 19804‐1621 Phone: (941) 637‐5673 Phone: (302) 998‐0745 District: Charlotte County Public School District: Delaware Military Academy Page 1 of 6 2019 National Blue Ribbon Schools High Schools Georgia William Fremd High School Pierce County High School 1000 S Quentin Rd 4850 County Farm Road Palatine, IL 60067‐7018 Blackshear, GA 31516‐8599 Phone: (847) 755‐2610 Phone: (912) 449‐2055 District: Township High School 211 District: Pierce County School Kentucky Illinois Notre Dame Academy (Non‐Public) Adlai E. -

Hoboken Public Schools

HOBOKEN PUBLIC SCHOOLS COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 Hoboken, New Jersey COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT of the Hoboken School District Hoboken, New Jersey For The Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2016 Prepared by Business Office HOBOKEN PUBLIC SCHOOLS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter of Transmittal i-v Organizational Chart vi Roster of Officials vii Consultants and Advisors viii Certificates of Achievement for Excellence in Financial Reporting ix-xii FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditor's Report 1-3 Management's Discussion and Analysis 4-16 Basic Financial Statements A. District-wide Financial Statements A-1 Statement of Net Position 17 A-2 Statement of Activities 18-19 B. Fond Financial Statements Governmental Funds B-1 Balance Sheet 20-21 B-2 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances 22 B-3 Reconciliation of the Governmental Funds Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances with the District-Wide Statements 23 Proprietary Funds B-4 Statement of Net Position 24 B-5 Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Position 25 B-6 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Fiduciary Funds B-7 Statement of Fiduciary Net Position 27 Notes to the Financial Statements 28-62 REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION- PART II C. Budgetary Comparison Schedules C-1 Budgetary Comparison Schedule- General Fund 63-71 C-Ia Combining Budgetary Comparison Schedule- General Fund 72-79 C-2 Budgetary Comparison Schedule- Special Revenue Fund 80 HOBOKEN PUBLIC SCHOOLS TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTES TO THE REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION- PART II C. Budgetary Comparison Schedules (Continued) C-3 Required Supplementary Information- Budgetary Comparison Schedule Notes to the Required Supplementary Information 81 REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION -PART lll L. -

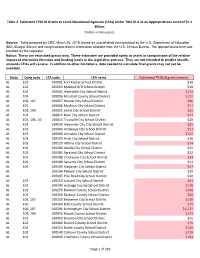

Page 1 of 283 State Cong Code LEA Code LEA Name Estimated FY2018

Table 2. Estimated FY2018 Grants to Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) Under Title IV-A at an Appropriations Level of $1.1 Billion Dollars in thousands Source: Table prepared by CRS, March 26, 2018, based on unpublished data provided by the U.S. Department of Education (ED), Budget Service and congressional district information available from the U.S. Census Bureau. The appropriations level was provided by the requester. Notice: These are estimated grants only. These estimates are provided solely to assist in comparisons of the relative impact of alternative formulas and funding levels in the legislative process. They are not intended to predict specific amounts LEAs will receive. In addition to other limitations, data needed to calculate final grants may not yet be available. State Cong code LEA code LEA name Estimated FY2018 grant amount AL 102 100001 Fort Rucker School District $10 AL 102 100003 Maxwell AFB School District $10 AL 104 100005 Albertville City School District $153 AL 104 100006 Marshall County School District $192 AL 106, 107 100007 Hoover City School District $86 AL 105 100008 Madison City School District $57 AL 103, 106 100011 Leeds City School District $32 AL 104 100012 Boaz City School District $41 AL 103, 106, 107 100013 Trussville City School District $20 AL 103 100030 Alexander City City School District $83 AL 102 100060 Andalusia City School District $51 AL 103 100090 Anniston City School District $122 AL 104 100100 Arab City School District $26 AL 105 100120 Athens City School District $54 AL 104 100180 Attalla -

ESEA Waiver - School Profiles 2014

ESEA Waiver - School Profiles 2014 17-0220-020 Bayonne Board of Education Bayonne High School This table presents the participation and performance determinations for this school under ESEA Flexibility. School Performance - English Language Arts Statewide Participation Rate - 95% Statewide Performance Goal - 90% # Enrolled % Not Met Total Valid % Target Met Subgroup Tested Participation Scores Proficient Performance Schoolwide 556 0.2 YES 520 93.5 90 MET GOAL White 276 0.0 YES 261 94.2 90 MET GOAL Black 53 0.0 YES 50 90.0 90 MET GOAL Hispanic 190 0.5 YES 176 92.6 90 MET GOAL American Indian 0 0.0 - 0 0.0 - - Asian 35 0.0 - 32 96.9 90 MET GOAL Two or More Races 2 0.0 - 1 100.0 - - Students with Disabilities 65 0.0 YES 60 66.7 79.2 NO Limited English Proficiency 22 0.0 - 11 36.4 - - Economically Disadvantaged 316 0.0 YES 293 89.7 90 YES* School Performance - Mathematics Statewide Participation Rate - 95% Statewide Performance Goal - 90% # Enrolled % Not Met Total Valid % Target Met Subgroup Tested Participation Scores Proficient Performance Schoolwide 556 0.2 YES 520 87.1 89.1 YES* White 276 0.0 YES 261 90.8 90 MET GOAL Black 53 0.0 YES 50 78.0 80.6 YES* Hispanic 190 0.5 YES 176 84.1 84.2 YES* American Indian 0 0.0 - 0 0.0 - - Asian 35 0.0 - 32 87.6 90 YES* Two or More Races 2 0.0 - 1 100.0 - - Students with Disabilities 65 0.0 YES 60 41.6 49.4 YES* Limited English Proficiency 22 0.0 - 11 54.5 - - Economically Disadvantaged 316 0.0 YES 293 83.2 87.9 NO Only Includes full year students for performance (Time In School < Year students are -

Why Middle-Class Parents in New Jersey Should Be Concerned About Their Local Public Schools

Not As Good as You Think Why Middle-Class Parents in New Jersey Should be Concerned About Their Local Public Schools By Lance Izumi, J.D. with Alicia Chang Ph.D. 1 Not As Good as You Think Why Middle-Class Parents in New Jersey Should be Concerned About Their Local Public Schools By Lance Izumi, J.D. with Alicia Chang Ph.D. NOT AS GOOD AS YOU THINK Why Middle-Class Parents in New Jersey Should Be Concerned about Their Local Public Schools by Lance Izumi, J.D. with Alicia Chang, Ph.D. February 2016 ISBN: 978-1-934276-24-2 Pacific Research Institute 101 Montgomery Street, Suite 1300 San Francisco, CA 94104 Tel: 415-989-0833 Fax: 415-989-2411 www.pacificresearch.org Download copies of this study at www.pacificresearch.org. Nothing contained in this report is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Pacific Research Institute or as an attempt to thwart or aid the passage of any legislation. ©2016 Pacific Research Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publi- cation may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or other- wise, without prior written consent of the publisher. Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary............................................................................................... 5 Introduction and Background on “Not As Good As You Think” Research ................ 8 Performance of New Jersey Students -

Directory of New Jersey Schools Serving Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Directory of New Jersey Schools Serving Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders 800.4.AUTISM [email protected] www.autismnj.org Directory of New Jersey Schools Serving Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders About this Directory Autism New Jersey maintains this directory as a service to families, school districts and other professionals. The information listed was provided by each school, and their inclusion in this directory should not be considered an endorsement by Autism New Jersey. We do not claim to have personal knowledge of any of the schools, and we do not evaluate an individual school’s interpretation or implementation of its educational methodologies. We urge you to make independent judgment when selecting a school program. Please remember that any program chosen for a child with an autism spectrum disorder should be based on the child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). Parents and child study team members should work together to develop the child’s IEP and then select the most appropriate program based on the completed IEP. How to Use this Directory Schools are listed by county, and grouped by type: public and private. Each listing includes the length of the school year and ages served (ESY = Extended School Year). When provided to us, we also include if the school offers the following services: Home Program, Parent Training, Parent Support Group, and After School Program. Please contact the school directly for more specific information. Please contact us if you are aware of schools that are not listed here. Updated September 2009 This directory is a service of Autism New Jersey. -

ESEA Waiver - Annual Progress Targets

ESEA Waiver - Annual Progress Targets CDS CODE : 17-0220-020 DISTRICT : Bayonne Board of Education SCHOOL : Bayonne High School The tables represent the annual proficiency targets, established for this School under ESEA Waiver Schools and Subgroups could meet expectations either by meeting the statewide proficiency rate of 90 percent, or reaching their individually determined progress targets. The statewide proficiency rate will be increased to 95 percent in 2015. Performance Targets - Language Arts Literacy # of Valid Baseline Yearly Baseline 2011-2012 2012-2013 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 Subgroup Test Scores % Proficient Increment year Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Schoolwide 526 95.2 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 White 275 96 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 Black 50 96 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 Hispanic 168 93.4 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 American Indian - - - 1011 - - - - - - Asian 32 96.9 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 Two or More Races - - - 1011 - - - - - - Students with Disabilities 65 72.3 2.3 1011 74.6 76.9 79.2 81.5 83.8 86.1 Limited English Proficiency - - - 1011 - - - - - - Economically Disadvantaged 253 95.7 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 Performance Targets - Mathematics # of Valid Baseline Yearly Baseline 2011-2012 2012-2013 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 Subgroup Test Scores % Proficient Increment year Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Schoolwide 525 85.5 1.2 1011 86.7 87.9 89.1 90 90 90 White 274 90.5 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 Black 50 74 2.2 1011 -

ESEA Waiver - Annual Progress Targets

ESEA Waiver - Annual Progress Targets CDS CODE : 03-0040-888 DISTRICT : ALLENDALE BOARD OF EDUCATION SCHOOL : DISTRICT LEVEL The tables represent the annual proficiency targets, established for this School under ESEA Waiver Schools and Subgroups could meet expectations either by meeting the statewide proficiency rate of 90 percent, or reaching their individually determined progress targets. The statewide proficiency rate will be increased to 95 percent in 2015. Performance Targets - Language Arts Literacy # of Valid Baseline Yearly Baseline 2011-2012 2012-2013 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 Subgroup Test Scores % Proficient Increment year Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Schoolwide 538 88.2 1 1011 89.2 90 90 90 90 90 White 464 89.2 .9 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 Black - - - 1011 - - - - - - Hispanic - - - 1011 - - - - - - American Indian - - - 1011 - - - - - - Asian 51 88.3 1 1011 89.3 90 90 90 90 90 Two or More Races - - - 1011 - - - - - - Students with Disabilities 56 53.5 3.9 1011 57.4 61.3 65.2 69.1 73 76.9 Limited English Proficiency - - - 1011 - - - - - - Economically Disadvantaged - - - 1011 - - - - - - Performance Targets - Mathematics # of Valid Baseline Yearly Baseline 2011-2012 2012-2013 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 Subgroup Test Scores % Proficient Increment year Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Target (%P) Schoolwide 540 95.4 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 White 464 95.1 - 1011 90 90 90 90 90 90 Black - - - 1011 - - - - - - Hispanic - - - 1011 - - -

School Calendar Welcome to the 2018-2019 School Year

2018-2019 School Calendar Welcome to the 2018-2019 School Year On behalf of the Elizabeth Board of through a lend-lease program into munity and dedication to our students. Education, welcome to the 2018-2019 which the Elizabeth Board of Education To our families, we truly appreciate school year. We are excited for another entered during the 2017-2018 school your trust and support and encourage year that will undoubtedly provide us year, the 2018-2019 budget includes you to actively join us in preparing our many opportunities to celebrate the funding for necessary capital project students for future success. I welcome successes of our students and district upgrades that Elizabeth Public Schools Elizabeth families who would like to team members. will be able to fast-track for the 2018- discuss any issues or concerns pertain- 2019 School year, including roof repair ing to the Elizabeth Public Schools to I am confident that this school year will or replacement, installation of air con- make an appointment to meet with me once again prove to be beneficial to ditioning, and replacement of chillers during the designated office hours of the values and needs of our students, at several district schools. 5:30-7:00 pm every Tuesday. families, and the greater community as we provide our students with the tools In addition to the capital projects we Let’s open our hearts and continue to necessary to achieve at high levels. have been able to complete and those work together this year to ensure that for which we have planned, we were every child achieves excellence. -

Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Hoboken Historic District City of Hoboken, Hudson County, New Jersey

Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Hoboken Historic District City of Hoboken, Hudson County, New Jersey Final Report Prepared for: State of New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Property Management and Construction and New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office DPMC Contract #: P1187-00 April 26, 2019 Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Project number: DPMC Contract #: P1187-00 Hoboken Historic District Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Emily Paulus Everett Sophia Jones Daniel Eichinger Senior Preservation Planner Director of Historic Preservation Project Administrator Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 1 4/22/19 Draft revision Yes E. Everett Sr. Preservation Planner Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name 1 Yes NJ HPO 1 Yes City of Hoboken Prepared for: State of New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Property Management and Construction AECOM Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Project number: DPMC Contract #: P1187-00 Hoboken Historic District Prepared for: State of New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Property Management and Construction Erin Frederickson, Project Manager New Jersey Historic Preservation Office Department of Environmental Protection Mail Code 501-04B PO Box 420 501 E State Street Trenton, NJ 08625 Prepared by: Emily Paulus Everett, AICP Senior Preservation Planner Samuel A. Pickard Historian Samantha Kuntz, AICP Preservation Planner AECOM 437 High Street Burlington NJ, 08016 -

New Jersey Districts Using Teachscape Tools Contact Evan Erdberg, Director of North East Sales, for More Information. Email

New Jersey Districts using Teachscape Tools Contact Evan Erdberg, Director of North East Sales, for more information. Email: [email protected] Mobile: 646.260.6931 ATLANTIC Atlantic County Institute of Technology Egg Harbor City Public School District Galloway Township Public Schools Mullica Township School District Richard Stockton College BERGEN Alpine School District Bergen County Special Services School District Bergen County Technical School District Bergenfield Public Schools Carlstadt East Rutherford Regional School District Carlstadt School District Cresskill School District Emerson School District Englewood Cliffs Public Schools Fort Lee Public Schools Glen Rock School District Hasbrouck Heights School District Leonia School District Maywood School District Midland Park School District New Milford School District Sage Day Schools South Bergen Jointure Commission Teaneck School District Tenafly Public Schools Wallington Public Schools Wood Ridge School District BURLINGTON Bass River Township School District Beverly City School District Bordentown Regional School District Delanco Township School District Delran Township School District Edgewater Park Township School District Evesham Township School District Mansfield Township School District Medford Lakes School District Palmyra Public Schools Pemberton Township School District Riverton School District Southampton Township Schools Springfield Township School District Tabernacle School District CAMDEN Camden Diocese Lindenwold School District Voorhees Township School District -

Updated NJ Rankings.Xlsx

New Jersey School Relative Efficiency Rankings ‐ Outcome = Student Growth 2012, 2013, 2014 (deviations from other schools in same county, controlling for staffing expenditure per pupil, economies of scale, grade range & student populations) 3 Year Panel Separate Yearly Model (Time Models (5yr Avg. Varying School School District School Grade Span Characteristics) Ranking 1 Characteristics) Ranking 2 ESSEX FELLS SCHOOL DISTRICT Essex Fells Elementary School PK‐06 2.92 23.44 1 Upper Township Upper Township Elementary School 03‐05 3.00 12.94 2 Millburn Township Schools Glenwood School KG‐05 2.19 62.69 3 Hopewell Valley Regional School District Toll Gate Grammar School KG‐05 2.09 10 2.66 4 Verona Public Schools Brookdale Avenue School KG‐04 2.33 42.66 5 Parsippany‐Troy Hills Township Schools Northvail Elementary School KG‐05 2.35 32.56 6 Fort Lee Public Schools School No. 1PK‐06 2.03 12 2.50 7 Ridgewood Public Schools Orchard Elementary School KG‐05 1.88 17 2.43 8 Discovery Charter School DISCOVERY CS 04‐08 0.89 213 2.42 9 Princeton Public Schools Community Park School KG‐05 1.70 32 2.35 10 Hopewell Valley Regional School District Hopewell Elementary School PK‐05 1.65 37 2.35 11 Cresskill Public School District Merritt Memorial PK‐05 1.69 33 2.33 12 West Orange Public Schools REDWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL KG‐05 1.81 21 2.28 13 Millburn Township Schools South Mountain School PK‐05 1.93 14 2.25 14 THE NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS ELLIOTT STREET ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK‐04 2.15 82.25 15 PATERSON PUBLIC SCHOOLS SCHOOL 19 KG‐04 1.95 13 2.24 16 GALLOWAY TOWNSHIP