Anthropological Science 107 (2), 141-188, 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

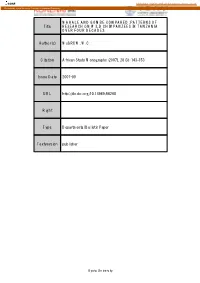

Title MAHALE and GOMBE COMPARED: PATTERNS

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository MAHALE AND GOMBE COMPARED: PATTERNS OF Title RESEARCH ON WILD CHIMPANZEES IN TANZANIA OVER FOUR DECADES Author(s) McGREW, W.C. Citation African Study Monographs (2007), 28(3): 143-153 Issue Date 2007-09 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68260 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 28(3): 143-153, September 2007 143 MAHALE AND GOMBE COMPARED: PATTERNS OF RESEARCH ON WILD CHIMPANZEES IN TANZANIA OVER FOUR DECADES W.C. McGREW Departments of Anthropology and Zoology, Miami University and Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies, University of Cambridge ABSTRACT Students of science have contrasted Japanese and Western primatology. This paper aims to test such claims by comparing two long-term African field projects, Mahale and Gombe, in terms of research productivity as measured by scientific publications. Gombe, directed by Jane Goodall since 1960, and Mahale, directed by Toshisada Nishida since 1965, have much in common, in addition to their main focus on the eastern chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii. They have produced similar total numbers of journal articles, books and chapters since the projects were founded. When these are categorized by subject matter, the main topics make up a similar proportion of publications, e.g. social relations, behavioural ecology, sex and reproduction, etc. Although most research output is on similar subjects, there are important differences between the sites, e.g. Mahale emphasizing medici- nal plant use, Gombe predominating in modelling human evolution. Both sites favour pub- lishing in Primates among the specialist primatological journals, but important differences exist in publishing elsewhere. -

Pan Africa News 15(1) PDF(651Kb)

Pan Africa News TheThe Newsletter Newsletter of the of theCommittee Committee for forthe theCare Care andand Conservation Conservation of ofChimpanzees, Chimpanzees, and and the the MahaleMahale Wildlife Wildlife Conservation Conservation Society Society JUNE 2008 VOL. 15, NO. 1 P. A . N . EDITORIAL STAFF Contents Chief Editor: <NEWS> Toshisada Nishida, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan Drs. Jane Goodall and Toshisada Nishida win 2008 Leakey Deputy Chief Editors: Prize! / Dr. Toshisada Nishida wins 2008 IPS Lifetime Kazuhiko Hosaka, Kamakura Women’s University, Japan Achievement Award! 1 Michio Nakamura, Kyoto University, Japan <ARTICLE> Associate Editors: Hunting with tools by Mahale chimpanzees Christophe Boesch, Max-Planck Institute, Germany Michio Nakamura & Noriko Itoh 3 Jane Goodall, Jane Goodall Institute, USA Takayoshi Kano, Kyoto University, Japan <NOTE> Tetsuro Matsuzawa, Kyoto University, Japan Snare removal by a chimpanzee of the Sonso community, William C. McGrew, University of Cambridge, UK Budongo Forest (Uganda) John C. Mitani, University of Michigan, USA Stephen Amati, Fred Babweteera & Roman M Wittig 6 Vernon Reynolds, Budongo Forest Project, UK <NOTE> Yukimaru Sugiyama, Kyoto University, Japan Use of wet hair to capture swarming termites by a Richard W. Wrangham, Harvard University, USA chimpanzee in Mahale, Tanzania Editorial Secretaries: Mieko Kiyono-Fuse 8 Noriko Itoh, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan <FORUM> Koichiro Zamma, GARI Hayashibara, Japan Why were guava trees cut down in Mahale Park? The Agumi Inaba, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan question of exterminating all introduced plants Toshisada Nishida 12 Instructions for Authors: Pan Africa News publishes articles, notes, reviews, forums, news, essays, book reviews, letters to <NEWS> editor, and classified ads (restricted to non-profit organizations) on any aspect of conservation and Drs. -

Title Tribute to Prof. Toshisada Nishida Author(S) Reynolds

Title Tribute to Prof. Toshisada Nishida Author(s) Reynolds, Vernon Citation Pan Africa News (2011), 18(special issue): 2-2 Issue Date 2011-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/147294 Right Copyright © Pan Africa News. Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University 2 Pan Africa News, 18 special issue, September 2011 His passing cannot be mourned too much. He was a pio- neer in the study of wild chimpanzees. Since 1965, he Tribute to Prof. Toshisada maintained research at Mahale, Tanzania, and accumu- Nishida lated accomplishments unique to his team, rivaling an- other longtime chimpanzee researcher, Dr. Jane Goodall Vernon Reynolds whose work at Gombe is well known. He published many Oxford University, UK/Budongo Conservation Field Station excellent papers, for example, on patrilineal structure of I first met Prof. Nishida (“Toshi” as we came to know chimpanzee society, political strategy among males, and him) on a visit to the Mahale Mountains chimpanzee scientific documentation of newly discovered cultural project which I made in the late 1970s. I met up with behaviors. He was awarded the Leakey Prize and the In- my colleague Yuki Sugiyama in Dar es Salaam and we ternational Primatological Society Lifetime Achievement travelled across Tanzania to Kigoma. There we were sup- Award. In addition, he served as President of the Inter- posed to meet a boat from the chimp project which would national Primatological Society. These honors tell how take us down Lake Tanganyika to Mahale. But it turned highly he was esteemed internationally. out that the boat’s outboard motor was broken. We waited a few days during which we met Toshi and spent some time with him, talking about his work and the Mahale chimpanzees. -

Pan Africa News 16(1)

Pan Africa News TheThe Newsletter Newsletter of the of theCommittee Committee for forthe theCare Care andand Conservation Conservation of ofChimpanzees, Chimpanzees, and and the the MahaleMahale Wildlife Wildlife Conservation Conservation Society Society JUNE 2009 VOL. 16, NO. 1 P. A. N. EDITORIAL STAFF Contents Chief Editor: <NOTE> Toshisada Nishida, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan Flu-like epidemics in wild bonobos (Pan paniscus) at Wamba, the Luo Scientific Reserve, Democratic Republic of Deputy Chief Editors: Congo Kazuhiko Hosaka, Kamakura Women’s University, Japan Tetsuya Sakamaki, Mbangi Mulavwa & Takeshi Furuichi 1 Michio Nakamura, Kyoto University, Japan <NOTE> Grooming Hand-Clasp by Chimpanzees of the Mugiri Associate Editors: Community, Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve, Uganda Christophe Boesch, Max-Planck Institute, Germany Tim H. Webster, Phineas R. Hodson & Kevin D. Hunt 5 Jane Goodall, Jane Goodall Institute, USA <NOTE> Takayoshi Kano, Kyoto University, Japan Preliminary Report on Hand-Clasp Grooming in Tetsuro Matsuzawa, Kyoto University, Japan Sanctuary-Released Chimpanzees, Haut Niger National William C. McGrew, University of Cambridge, UK Park, Guinea John C. Mitani, University of Michigan, USA Tatyana Humle, Christelle Colin & Estelle Raballand 7 Vernon Reynolds, Budongo Forest Project, UK <Book Review> Yukimaru Sugiyama, Kyoto University, Japan Raymond Corbey, The Metaphysics of Apes. Negotiating the Richard W. Wrangham, Harvard University, USA Animal-Human Boundary, Cambridge University Press, Editorial Secretaries: Cambridge 2005 Noriko Itoh, Japan Monkey Center, Japan Paola Cavalieri 10 Koichiro Zamma, Hayashibara GARI, Japan Agumi Inaba, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan <NOTE> Instructions for Authors: Pan Africa News publishes articles, notes, reviews, Flu-like Epidemics in Wild forums, news, essays, book reviews, letters to editor, and classified ads (restricted to non-profit Bonobos (Pan paniscus) at organizations) on any aspect of conservation and research regarding chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Wamba, the Luo Scientific and bilias (Pan paniscus). -

Chapter 16.Qxp

BONOBO Sex & Society The behavior of a close relative challenges assumptions about male supremacy in human evolution BY FRANS B. M. DE WAAL t a juncture in history during which women are (although such contact among close family mem- Aseeking equality with men, science arrives with bers may be suppressed). And sexual interactions a belated gift to the feminist movement. Male- occur more often among bonobos than among other biased evolutionary scenarios—Man the Hunter, primates. Despite the frequency of sex, the Man the Toolmaker and so on—are being chal- bonobo’s rate of reproduction in the wild is about lenged by the discovery that females play a central, the same as that of the chimpanzee. A female gives perhaps even dominant, role in the social life of one birth to a single infant at intervals of between five of our nearest relatives. In the past two decades and six years. So bonobos share at least one very many strands of knowledge have come together important characteristic with our own species, concerning a relatively unknown ape with an namely, a partial separation between sex and repro- unorthodox repertoire of behavior: the bonobo. duction. The bonobo is one of the last large mammals to be found by science. The creature was discovered in EAR ELATIVE 1929 in a Belgian colonial museum, far from its A N R lush African habitat. A German anatomist, Ernst THIS FINDING commands attention because the Schwarz, was scrutinizing a skull that had been bonobo shares more than 98 percent of our genetic ascribed to a juvenile chimpanzee because of its profile, making it as close to a human as, say, a fox small size, when he realized that it belonged to an is to a dog. -

Title the Passing of Professor Toshisada Nishida Lamented

Title The Passing of Professor Toshisada Nishida Lamented Author(s) Kawai, Masao Citation Pan Africa News (2011), 18(special issue): 1-2 Issue Date 2011-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/147295 Right Copyright © Pan Africa News. Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Pan Africa News The Newsletter of the Committee for the Care and Conservation of Chimpanzees, and the Mahale Wildlife Conservation Society ISSN 1884-751X (print), 1884-7528 (online) mahale.main.jp/PAN/ SEPTEMBER 2011 VOL. 18, special issue P. A. N. EDITORIAL STAFF Chief Editor: Editorial Kazuhiko Hosaka, Kamakura Womenʼs University, Japan Deputy Chief Editor: Michio Nakamura, Kyoto University, Japan This special issue of Pan Associate Editors: Africa News is dedicated to Pro- Christophe Boesch, Max-Planck Institute, Germany fessor Toshisada Nishida who Jane Goodall, Jane Goodall Institute, USA passed away in June 2011. As Tetsuro Matsuzawa, Kyoto University, Japan readers may be aware, he was William C. McGrew, University of Cambridge, UK the first editor-in-chief of PAN, John C. Mitani, University of Michigan, USA and devoted his life to the study Vernon Reynolds, Budongo Forest Project, UK and conservation of wild chim- Yukimaru Sugiyama, Kyoto University, Japan Richard W. Wrangham, Harvard University, USA panzees. We asked those who Takeshi Furuichi, Kyoto University, Japan knew him very well, both from Japan and overseas, to contrib- Editorial Secretaries: ute their memories of Professor Nishida. These people Noriko Itoh, Kyoto University, Japan include senior and junior colleagues, friends, and Pro- Koichiro Zamma, Great Ape Research Institute, Hayashibara, Japan Agumi Inaba, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan fessor Nishida’s students who have conducted research on chimpanzees at Mahale. -

Featured Articles in This Month's Animal Behaviour

Animal Behaviour 85 (2013) 685–688 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Book Reviews Chimpanzees of the Lakeshore: Natural History and Culture at pattern called ‘leaf pile pulling’, and the habit of Mahale chimpan- Mahale. By Toshisada Nishida. Cambridge University Press, Cam- zees to scratch the backs of their friends (literally). bridge (2012). Pp. xixD320. Price $29.95 paperback One drawback to the book is that it suffers a bit of an identity crisis: the book seems to be trying simultaneously to be a reference Motivated by his quest to characterize the society of the last manual in which chapters can stand alone, but also to be a story common ancestor of humans and other great apes, Toshisada Nish- that one would read cover to cover. If a reader approaches the book ida set out as a graduate student to the Mahale Mountains on the in the latter fashion, as I did, the content can be repetitive, as readers eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika, Tanzania. This book is a story of are reintroduced to events and individuals (chimpanzee or human) his 45 years with the Mahale chimpanzees, or as he calls it, their described previously. However, this redundancy is a potential advan- ethnography. Beginning with his accounts of meeting the Tongwe tage to those who might wish to use each chapter independently as a people and the challenges of provisioning the chimpanzees for handbook of the behaviour of the Mahale chimpanzees, as the chap- habituation, Nishida reveals how he slowly unravelled the unit ters are divided into clearly labelled subsections. -

Toshisada Nishida (1941–2011): Chimpanzee Rapport

Obituary Toshisada Nishida (1941–2011): Chimpanzee Rapport Frans B. M. de Waal* Living Links, Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America ‘‘Chimpanzees are always new to me.’’ Toshisada Nishida [1] One of the absolute greats of primatol- ogy, Toshisada Nishida (March 3, 1941– June 7, 2011), recently passed away at the age of 70 (Figure 1). We have come such a long way in our knowledge of chimpan- zees, and the discoveries have reached us in such a gradual and cumulative fashion, that it is easy to forget how little was known when Nishida set out for Africa to establish one of the first chimpanzee field sites, in 1965. At the time, chimpanzees did not yet occupy the special place in our thinking about human evolution reserved for them today. Science considered ba- boons the best model of human evolution, since baboons had descended from the trees to become savanna-dwellers, like our ancestors. These rambunctious monkeys, however, are genetically more distant from us, and many of the characteristics deemed important for human evolution Figure 1. Toshisada Nishida in a Kyoto temple, in 2007. Photograph by Frans de Waal. are either absent or minimally developed, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001185.g001 such as tool technology, cooperative hunt- ing, food sharing, territoriality, cultural patiently for chimpanzees at a patch of any need for social bonds—not unlike traditions, and certain cognitive capacities, sugar cane planted to attract them. The Rousseau’s noble savages—Nishida had such as planning and theory-of-mind. primates started to make regular visits only noticed that chimpanzees live a communal Chimpanzees show all of them. -

Silent Invasion: Imanishi's Primatology and Cultural Bias in Science

Anim Cogn (2003) 6 : 293–299 DOI 10.1007/s10071-003-0197-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Frans B. M. de Waal Silent invasion: Imanishi’s primatology and cultural bias in science Received: 29 July 2002 / Revised: 5 November 2002 / Accepted: 1 September 2003 / Published online: 10 October 2003 © Springer-Verlag 2003 When it comes to our relation with nature, there is no es- nese saw it in terms of complementary roles within the caping the tension between perception and projection. ecosystem. While the two teams agreed on the data, they What we discover in nature is often what we put into it in operated on the basis of strikingly different outlooks. the first place. Consequently, the way naturalists have East–West disagreements about the naturalness of com- contributed to humanity’s know-thyself mission can be petition versus cooperation go back at least to the late 19th understood only in the context of the stained glasses century debate between Thomas Henry Huxley and Petr through which they stare in nature’s mirror. Given that Kropotkin, in which the former took a “gladiatorial” view these glasses cannot be taken off, the next best thing is to of nature and the latter advocated a more synergistic model compare alternative ones. (Todes 1989; de Waal 1996). These disagreements rarely The present essay explores cultural bias in the context show a clear winner. They rather tend to have the flavor of of my own little corner of science, which is the behavior the-glass-is-half-full versus the-glass-is-half-empty debate. of monkeys and apes. -

Toshisada Nishida (March 3, 1941– June 7, 2011)

Int J Primatol (2012) 33:10–18 DOI 10.1007/s10764-011-9571-2 Obituary: Toshisada Nishida (March 3, 1941– June 7, 2011) John C. Mitani & Frans B. M. de Waal & Kazuhiko Hosaka & William C. McGrew & Michio Nakamura & Akisato Nishimura & Richard W. Wrangham & Juichi Yamigiwa Published online: 15 December 2011 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 Toshisada Nishida, a pioneer in the study of primate behavior, died on June 7, 2011 following a prolonged battle with cancer. He was 70 years old. Nishida began his career while still an undergraduate student at Kyoto University, where he was inspired by Kinji Imanishi. In 1962, he investigated interactions between two groups of Formosan macaques that had been translocated to Japan. He followed this in 1963 with a study of Japanese macaques living at the northern limit of their geographical distribution. He continued to study Japanese macaques from 1964 to 1965 for his Master’s thesis at Kyoto. Working under the supervision of Junichiro Itani, he described the life of solitary male macaques and how they transfer J. C. Mitani (*) Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA e-mail: [email protected] F. B. M. de Waal Living Links, Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA K. Hosaka Faculty of Child Studies, Kamakura Women’s University, Kamakura 247-8512, Japan W. C. McGrew Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1QH, UK M. Nakamura Wildlife Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8203, Japan A. Nishimura Iwakura Kino-cho 251-28, Kyoto 601-1125, Japan R. -

Is Lethal Violence an Integral Part of Chimpanzee Society? Like It Or Not, Yes

Is lethal violence an integral part of chimpanzee society? Like it or not, yes. Kevin D. Hunt Indiana University In her March 29, 2011 blog post, “Male chimps and humans are genetically violent— NOT!” Darcia Narvaez asks “is violence in our genes? Do chimpanzees in the wild want to kill others?” She concludes that evidence that lethal violence plays a critical role in chimpanzee society is flimsy. Narvaez, who is a psychologist by training, relied on a 2009 book Donna Hart and Bob Sussman and a 20‐year‐old book by Margaret Power for her information. These authors maintain that deadly chimp‐on‐chimp violence is so rare we can conclude little from the few instances where it has been seen, and that in many cases the evidence is over‐interpreted and exaggerated. Full disclosure: Richard Wrangham, a coauthor of Demonic Males, a book many view as the quintessence of the chimps‐are‐murderers view, was my doctoral co‐supervisor. In responding to the rarity of our observations of chimpanzee murders, I can’t help returning to that old saw, the proverbial Martian anthropologist sent to earth disguised as a human to study human society. Let’s imagine she logs many hours studying people in my hometown, Bloomington. While her language and cognitive capacities are bizarrely different from ours, leaving it nearly impossible for her to understand human language or even to de‐code the written word, she is a keen observer. I see her around town often at public gatherings, watching people, making notes. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to me, there are other Martians studying humans, too. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01578-4 - Chimpanzees of the Lakeshore: Natural History and Culture at Mahale Toshisada and Nishida Frontmatter More information Chimpanzees of the Lakeshore Chimpanzees are humanitys closest living relations, and are of enduring interest to a range of sciences, from anthropology to zoology. In the West, many know of the pioneering work of Jane Goodall, whose studies of these apes at Gombe in Tanzania are justly famous. Less well-known, but equally important, are the studies carried out by Toshisada Nishida on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. Comparison between the two sites yields both notable similarities and startling contrasts. Nishida has written a comprehensive synthesis of his work on the behaviour and ecology of the chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains. With topics ranging from individual development to population-specific behavioural patterns, it reveals the complexity of social life, from male struggles for dominant status to female travails in raising offspring. Richly illustrated, the author blends anecdotes with powerful data to explore the fascinating world of the chimpanzees of the lakeshore. TOSHISADA NISHIDA (1941–2011) was Executive Director of the Japan Monkey Centre and Editor-in-Chief of the journal Primates.He conducted pioneering field studies into the behaviour and ecology of wild chimpanzees for more than 45 years. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01578-4 - Chimpanzees of the Lakeshore: Natural History