Silent Invasion: Imanishi's Primatology and Cultural Bias in Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of HOPE Project

February, 2004 Prof. Tetsuro Matsuzawa Kyoto University, Japan Summary of HOPE Project The human mind is as much a product of evolution as the human body. Where did we come from? What is human nature? To answer such fundamental questions, we must address the question of how humans have evolved. Humans (scientific name Homo sapiens) are a species of primate, a species of mammal, and a species of vertebrate. The HOPE project aims to study the “Primate Origins of Human Evolution” focusing on apes and monkeys as our evolutionary neighbors. HOPE is an anagram of our research title, and also expresses a hope for conservation. All primate species other than humans are designated as endangered or threatened in CITES (Washington convention on endangered animals and plants). Therefore, in parallel to advanced studies of primates, we must also make concentrated efforts for the conservation of monkeys and apes in tropical forests, as species symbolic of biological diversity and the global environment. Japan is unique among the advanced countries of the world in having an indigenous species of nonhuman primate. Thanks to the country’s natural and cultural background, Japanese primatological study has made unique contributions to the world. The late Kinji Imanishi (1902-1992) and his colleagues began the study of wild monkeys in Koshima, Miyazaki, Japan, in 1948. The study of Koshima monkeys continues to be conducted by the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University (KUPRI) to the present day. Fifty-five years have passed, throughout which researchers kept records of monkeys of eight generations: the history of a monkey kingdom. -

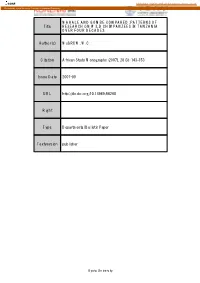

Title MAHALE and GOMBE COMPARED: PATTERNS

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository MAHALE AND GOMBE COMPARED: PATTERNS OF Title RESEARCH ON WILD CHIMPANZEES IN TANZANIA OVER FOUR DECADES Author(s) McGREW, W.C. Citation African Study Monographs (2007), 28(3): 143-153 Issue Date 2007-09 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68260 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 28(3): 143-153, September 2007 143 MAHALE AND GOMBE COMPARED: PATTERNS OF RESEARCH ON WILD CHIMPANZEES IN TANZANIA OVER FOUR DECADES W.C. McGREW Departments of Anthropology and Zoology, Miami University and Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies, University of Cambridge ABSTRACT Students of science have contrasted Japanese and Western primatology. This paper aims to test such claims by comparing two long-term African field projects, Mahale and Gombe, in terms of research productivity as measured by scientific publications. Gombe, directed by Jane Goodall since 1960, and Mahale, directed by Toshisada Nishida since 1965, have much in common, in addition to their main focus on the eastern chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii. They have produced similar total numbers of journal articles, books and chapters since the projects were founded. When these are categorized by subject matter, the main topics make up a similar proportion of publications, e.g. social relations, behavioural ecology, sex and reproduction, etc. Although most research output is on similar subjects, there are important differences between the sites, e.g. Mahale emphasizing medici- nal plant use, Gombe predominating in modelling human evolution. Both sites favour pub- lishing in Primates among the specialist primatological journals, but important differences exist in publishing elsewhere. -

Pan Africa News 15(1) PDF(651Kb)

Pan Africa News TheThe Newsletter Newsletter of the of theCommittee Committee for forthe theCare Care andand Conservation Conservation of ofChimpanzees, Chimpanzees, and and the the MahaleMahale Wildlife Wildlife Conservation Conservation Society Society JUNE 2008 VOL. 15, NO. 1 P. A . N . EDITORIAL STAFF Contents Chief Editor: <NEWS> Toshisada Nishida, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan Drs. Jane Goodall and Toshisada Nishida win 2008 Leakey Deputy Chief Editors: Prize! / Dr. Toshisada Nishida wins 2008 IPS Lifetime Kazuhiko Hosaka, Kamakura Women’s University, Japan Achievement Award! 1 Michio Nakamura, Kyoto University, Japan <ARTICLE> Associate Editors: Hunting with tools by Mahale chimpanzees Christophe Boesch, Max-Planck Institute, Germany Michio Nakamura & Noriko Itoh 3 Jane Goodall, Jane Goodall Institute, USA Takayoshi Kano, Kyoto University, Japan <NOTE> Tetsuro Matsuzawa, Kyoto University, Japan Snare removal by a chimpanzee of the Sonso community, William C. McGrew, University of Cambridge, UK Budongo Forest (Uganda) John C. Mitani, University of Michigan, USA Stephen Amati, Fred Babweteera & Roman M Wittig 6 Vernon Reynolds, Budongo Forest Project, UK <NOTE> Yukimaru Sugiyama, Kyoto University, Japan Use of wet hair to capture swarming termites by a Richard W. Wrangham, Harvard University, USA chimpanzee in Mahale, Tanzania Editorial Secretaries: Mieko Kiyono-Fuse 8 Noriko Itoh, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan <FORUM> Koichiro Zamma, GARI Hayashibara, Japan Why were guava trees cut down in Mahale Park? The Agumi Inaba, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan question of exterminating all introduced plants Toshisada Nishida 12 Instructions for Authors: Pan Africa News publishes articles, notes, reviews, forums, news, essays, book reviews, letters to <NEWS> editor, and classified ads (restricted to non-profit organizations) on any aspect of conservation and Drs. -

Déroutants Primates : Approches Émergentes Aux Frontières De L’Anthropologie Et De La Primatologie

5 | 2013 Varia http://primatologie.revues.org/1250 Dossier Déroutants primates : approches émergentes aux frontières de l’anthropologie et de la primatologie Special section on Disconcerting primates: emerging approaches in the anthropology/primatology borderland Dossier proposé et édité avec le concours de la revue par Vincent Leblan Vincent Leblan Introduction: emerging approaches in the anthropology/primatology borderland [Texte intégral] Introduction : approches émergentes aux frontières de l’anthropologie et de la primatologie Article 62 Takanori Oishi 5 | 2013 Varia http://primatologie.revues.org/1250 Human-Gorilla and Gorilla-Human: Dynamics of Human-animal boundaries and interethnic relationships in the central African rainforest [Texte intégral] Homme-gorilles et gorille-hommes : dynamiques de la frontière homme-animal et relations interethniques dans la forêt d’Afrique centrale Article 63 Gen Yamakoshi et Vincent Leblan Conflicts between indigenous and scientific concepts of landscape management for wildlife conservation: human-chimpanzee politics of coexistence at Bossou, Guinea [Texte intégral] Conflits entre conceptions locales et scientifiques de la gestion du paysage pour la conservation de la faune : politiques de la coexistence entre humains et chimpanzés à Bossou, Guinée Article 64 Naoki Matsuura, Yuji Takenoshita et Juichi Yamagiwa Eco-anthropologie et primatologie pour la conservation de la biodiversité : un projet collaboratif dans le Parc National de Moukalaba-Doudou, Gabon [Texte intégral] Ecological anthropology -

Professor Masao Kawai, a Pioneer and Leading Scholar in Primatology and Writer of Animal Stories for Children

Primates (2021) 62:677–695 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-021-00938-2 EDITORIAL Professor Masao Kawai, a pioneer and leading scholar in primatology and writer of animal stories for children Masayuki Nakamichi1 Received: 20 July 2021 / Accepted: 28 July 2021 / Published online: 24 August 2021 © Japan Monkey Centre 2021 This Editorial is dedicated to Professor Masao Kawai (Fig. 1), who passed away on May 14th, 2021. He served as the sixth Editor-in-Chief of Primates for 15 years (1981–1995). The following is a collection of memories from 20 scholars. A last eulogy for Prof. Kawai by his last student Naofumi Nakagawa Professor Emeritus Masao Kawai is one of the so-called frst generation of Japanese primatologists, comprising students of Kinji Imanishi, the pioneer of the discipline of Japanese primatology (Matsuzawa and Yamagiwa 2018), and the frst president of the Primate Society of Japan (Kawai 1985). It is my honor and privilege to deliver this memorial address for Prof. Kawai as one of his last students. Prof. Kawai served as my mentor until his retirement from the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University (KUPRI), when I was in the frst year of my doctoral study. Although I am now 61, when I frst met him, I quickly realized that I was no match for his extensive knowledge and enlightened spirit, which led to a wide range of human networks. Prof. Kawai was so busy that it was very difcult for me to see him; however, whenever I happened to see him in a meeting room during lunchtime, or to meet with him in his own ofce, he would talk to me in a friendly manner with much humor, while providing profound insights. -

Title Tribute to Prof. Toshisada Nishida Author(S) Reynolds

Title Tribute to Prof. Toshisada Nishida Author(s) Reynolds, Vernon Citation Pan Africa News (2011), 18(special issue): 2-2 Issue Date 2011-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/147294 Right Copyright © Pan Africa News. Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University 2 Pan Africa News, 18 special issue, September 2011 His passing cannot be mourned too much. He was a pio- neer in the study of wild chimpanzees. Since 1965, he Tribute to Prof. Toshisada maintained research at Mahale, Tanzania, and accumu- Nishida lated accomplishments unique to his team, rivaling an- other longtime chimpanzee researcher, Dr. Jane Goodall Vernon Reynolds whose work at Gombe is well known. He published many Oxford University, UK/Budongo Conservation Field Station excellent papers, for example, on patrilineal structure of I first met Prof. Nishida (“Toshi” as we came to know chimpanzee society, political strategy among males, and him) on a visit to the Mahale Mountains chimpanzee scientific documentation of newly discovered cultural project which I made in the late 1970s. I met up with behaviors. He was awarded the Leakey Prize and the In- my colleague Yuki Sugiyama in Dar es Salaam and we ternational Primatological Society Lifetime Achievement travelled across Tanzania to Kigoma. There we were sup- Award. In addition, he served as President of the Inter- posed to meet a boat from the chimp project which would national Primatological Society. These honors tell how take us down Lake Tanganyika to Mahale. But it turned highly he was esteemed internationally. out that the boat’s outboard motor was broken. We waited a few days during which we met Toshi and spent some time with him, talking about his work and the Mahale chimpanzees. -

Mahale Chimpanzees: 50 Years of Research Edited by Michio Nakamura, Kazuhiko Hosaka, Noriko Itoh and Koichiro Zamma Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05231-4 - Mahale Chimpanzees: 50 Years of Research Edited by Michio Nakamura, Kazuhiko Hosaka, Noriko Itoh and Koichiro Zamma Frontmatter More information Mahale Chimpanzees 50 Years of Research Long-term ecological research studies are rare and invaluable resources, particularly when they are as thoroughly documented as the Mahale Mountains Chimpanzee Research Project in Tanzania. Directed by the late Toshisada Nishida from 1965 until 2011, the project continues to yield new and fascinating findings about our closest neighbor species. In a fitting tribute to Nishida’s contribution to science, this book brings together 50 years of research into one encyclopedic volume. Alongside previously unpublished data, the editors include new translations of Japanese writings throughout the book to bring previously inaccessible work to non-Japanese speakers. The history and ecology of the site, chimpanzee behavior and biology, and ecological management are all addressed through first-hand accounts by Mahale researchers. The authors highlight long-term changes in behavior, where possible, and draw comparisons with other chimpanzee sites across Africa to provide an integrative view of chimpanzee research today. This is a major contribution to great ape research, complementing Nishida’s last work Chimpanzees of the Lakeshore (Cambridge University Press, 2012). Michio Nakamura is Associate Professor at the Wildlife Research Center, Kyoto University, Japan. He has studied the Mahale chimpanzees since 1994 and is a recipient of the Primate Society of Japan’s Takashima Prize. Kazuhiko Hosaka is Associate Professor at Kamakura Women’s University, Japan. His research focuses on the social interactions, hunting, and meat-eating behavior of chimpanzees in relation to human evolution. -

Pan Africa News 16(1)

Pan Africa News TheThe Newsletter Newsletter of the of theCommittee Committee for forthe theCare Care andand Conservation Conservation of ofChimpanzees, Chimpanzees, and and the the MahaleMahale Wildlife Wildlife Conservation Conservation Society Society JUNE 2009 VOL. 16, NO. 1 P. A. N. EDITORIAL STAFF Contents Chief Editor: <NOTE> Toshisada Nishida, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan Flu-like epidemics in wild bonobos (Pan paniscus) at Wamba, the Luo Scientific Reserve, Democratic Republic of Deputy Chief Editors: Congo Kazuhiko Hosaka, Kamakura Women’s University, Japan Tetsuya Sakamaki, Mbangi Mulavwa & Takeshi Furuichi 1 Michio Nakamura, Kyoto University, Japan <NOTE> Grooming Hand-Clasp by Chimpanzees of the Mugiri Associate Editors: Community, Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve, Uganda Christophe Boesch, Max-Planck Institute, Germany Tim H. Webster, Phineas R. Hodson & Kevin D. Hunt 5 Jane Goodall, Jane Goodall Institute, USA <NOTE> Takayoshi Kano, Kyoto University, Japan Preliminary Report on Hand-Clasp Grooming in Tetsuro Matsuzawa, Kyoto University, Japan Sanctuary-Released Chimpanzees, Haut Niger National William C. McGrew, University of Cambridge, UK Park, Guinea John C. Mitani, University of Michigan, USA Tatyana Humle, Christelle Colin & Estelle Raballand 7 Vernon Reynolds, Budongo Forest Project, UK <Book Review> Yukimaru Sugiyama, Kyoto University, Japan Raymond Corbey, The Metaphysics of Apes. Negotiating the Richard W. Wrangham, Harvard University, USA Animal-Human Boundary, Cambridge University Press, Editorial Secretaries: Cambridge 2005 Noriko Itoh, Japan Monkey Center, Japan Paola Cavalieri 10 Koichiro Zamma, Hayashibara GARI, Japan Agumi Inaba, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan <NOTE> Instructions for Authors: Pan Africa News publishes articles, notes, reviews, Flu-like Epidemics in Wild forums, news, essays, book reviews, letters to editor, and classified ads (restricted to non-profit Bonobos (Pan paniscus) at organizations) on any aspect of conservation and research regarding chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Wamba, the Luo Scientific and bilias (Pan paniscus). -

Imanishi Kinji, a Japanese View of Nature --- Introduction

A Japanese View of Nature [*] A Japanese View of Nature—The World of Living Things by Kinji Imanishi Translated by Pamela J. Asquith, Heita Kawakatsu, Shusuke Yagi and Hiroyuki Takasaki Although Seibutsu no Sekai (The World of Living Things), the seminal 1941 work of Kinji Imanishi, had an enormous impact in Japan, both on scholars and on the general public, very little is known about it in the English-speaking world. This book makes the complete text available in English for the first time and provides an extensive introduction and notes to set the work in context. Imanishi's work, based on a wide knowledge of science and the natural world, puts forward a distinctive view of nature and how it should be studied. Ecologist, anthropologist, and founder of primatology in Japan, Imanishi's first book is a philosophical biology that informs many of his later ideas on species society, species recognition, culture in the animal world, cooperation and habitat segregation in nature, the "life" of nonliving things and the relationships between organisms and their environments. Imanishi's work is of particular interest for contemporary discussions of units and levels of selection in evolutionary biology and philosophy, and as a background to the development of some contributions to ecology, primatology and human social evolution theory in Japan. Imanishi's views are extremely interesting because he formulated an approach to viewing nature that challenged the usual international ideas of the time, and that foreshadows approaches to study of the biosphere that have currency today. Japan Anthropology Workshop Series (JAWS) Series editor: Joy Hendry, Oxford Brookes University Editorial board: Pamela J. -

Chapter 16.Qxp

BONOBO Sex & Society The behavior of a close relative challenges assumptions about male supremacy in human evolution BY FRANS B. M. DE WAAL t a juncture in history during which women are (although such contact among close family mem- Aseeking equality with men, science arrives with bers may be suppressed). And sexual interactions a belated gift to the feminist movement. Male- occur more often among bonobos than among other biased evolutionary scenarios—Man the Hunter, primates. Despite the frequency of sex, the Man the Toolmaker and so on—are being chal- bonobo’s rate of reproduction in the wild is about lenged by the discovery that females play a central, the same as that of the chimpanzee. A female gives perhaps even dominant, role in the social life of one birth to a single infant at intervals of between five of our nearest relatives. In the past two decades and six years. So bonobos share at least one very many strands of knowledge have come together important characteristic with our own species, concerning a relatively unknown ape with an namely, a partial separation between sex and repro- unorthodox repertoire of behavior: the bonobo. duction. The bonobo is one of the last large mammals to be found by science. The creature was discovered in EAR ELATIVE 1929 in a Belgian colonial museum, far from its A N R lush African habitat. A German anatomist, Ernst THIS FINDING commands attention because the Schwarz, was scrutinizing a skull that had been bonobo shares more than 98 percent of our genetic ascribed to a juvenile chimpanzee because of its profile, making it as close to a human as, say, a fox small size, when he realized that it belonged to an is to a dog. -

Newly-Acquired Pre-Cultural Behavior of the Natural Troop of Japanese Monkeys on Koshima Islet

PRIMATES, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1965 Newly-acquired Pre-cultural Behavior of the Natural Troop of Japanese Monkeys on Koshima Islet MASA0 KAWAI The Japan Monkey Centre, Aichi INTR OD UC TION The problem of pre-culture in the society of Japanese monkeys (Macaca ,/hscata) was first discussed and given a theoretical interpretation by K. Imanishi (1952). Since then the Primates Research Group has collected various kinds of data. A general view on the pre-culture* of Japanese monkeys was given by S. Kawamura (1956, '58, '59 and '64). Sweet-potato washing is an example of pre-culture characteristic of the troop of monkeys in Koshima (a small islet in Miyazaki Prefecture, Kyushu). This was already reported by Kawamura (1954, '56, '58, '59, and '64), D. Miyadi (1959), and Kawai (1964). Kawamura and I observed the habit of sweet-potato washing occurred in the Koshima troop in 1953, and since then I have paid much attention to observing the pre-cuhural phenomena (Kawai 1964 a, b). Besides the sweet-potato washing behavior, the Koshima troop acquired some other new behaviors, which can be regarded as the pre-culture peculiar to the troop. I would like to discuss here the sweet-potato washing pre-culture and the new pre-cultural phenomena, especially, their process of acquisition and propagation, their causes, and finally, the meaning of these pre-cultures. Before proceeding into the report, I should like to show my gratitude for the valuable advice and friendship of those who have long been with me in studying the Koshima Troop: Dr. Syunzo Kawamura of Osaka City Univer- sity, Dr. -

Title the Passing of Professor Toshisada Nishida Lamented

Title The Passing of Professor Toshisada Nishida Lamented Author(s) Kawai, Masao Citation Pan Africa News (2011), 18(special issue): 1-2 Issue Date 2011-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/147295 Right Copyright © Pan Africa News. Type Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Pan Africa News The Newsletter of the Committee for the Care and Conservation of Chimpanzees, and the Mahale Wildlife Conservation Society ISSN 1884-751X (print), 1884-7528 (online) mahale.main.jp/PAN/ SEPTEMBER 2011 VOL. 18, special issue P. A. N. EDITORIAL STAFF Chief Editor: Editorial Kazuhiko Hosaka, Kamakura Womenʼs University, Japan Deputy Chief Editor: Michio Nakamura, Kyoto University, Japan This special issue of Pan Associate Editors: Africa News is dedicated to Pro- Christophe Boesch, Max-Planck Institute, Germany fessor Toshisada Nishida who Jane Goodall, Jane Goodall Institute, USA passed away in June 2011. As Tetsuro Matsuzawa, Kyoto University, Japan readers may be aware, he was William C. McGrew, University of Cambridge, UK the first editor-in-chief of PAN, John C. Mitani, University of Michigan, USA and devoted his life to the study Vernon Reynolds, Budongo Forest Project, UK and conservation of wild chim- Yukimaru Sugiyama, Kyoto University, Japan Richard W. Wrangham, Harvard University, USA panzees. We asked those who Takeshi Furuichi, Kyoto University, Japan knew him very well, both from Japan and overseas, to contrib- Editorial Secretaries: ute their memories of Professor Nishida. These people Noriko Itoh, Kyoto University, Japan include senior and junior colleagues, friends, and Pro- Koichiro Zamma, Great Ape Research Institute, Hayashibara, Japan Agumi Inaba, Japan Monkey Centre, Japan fessor Nishida’s students who have conducted research on chimpanzees at Mahale.