Harnessing Socio-Cultural Constraints on Athlete Development To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Season Review

2017 Season Review Paul Hampton For the first time in Castleford’s 91 year history as a senior club they finished at the top of the table. After the regular season of 23 games the twelve team league split into the Super 8s at the top, with the bottom four joining with the Championship top four in the Qualifiers to determine promotion and relegation. Castleford finished the regular season at the top, ten points clear and maintained the lead to the end of the season. They were so far in front that the shield was awarded to them after only three games of the seven game series as they could not be caught. Final Table 2017 P W D L FOR AGST DIFF PTS Castleford Tigers 30 25 0 5 965 536 429 50 Leeds Rhinos 30 20 0 10 749 623 126 40 Hull FC 30 17 1 12 714 655 59 35 St Helens 30 16 1 13 663 518 145 33 Wakefield Trinity 30 16 0 14 745 648 97 32 Wigan Warriors 30 14 3 13 691 668 23 31 Salford Red Devils 30 14 0 16 680 728 -48 28 Huddersfield Giants 30 11 3 16 663 680 -17 25 The record breaking season was one of many achievements – • Luke Gale voted Man of Steel and RL Writers Association Player of the Year. He also won the League Express magazine Albert Goldthorpe Medal as Player of the Season for the third consecutive time. • Daryl Powell voted Coach of The Year • Castleford Tigers voted Club of The Year • Luke Gale topped the goal scoring list with 145 and was top points scorer in the league with 355 • Greg Eden was top try scorer in the League with 41 in all competitions • The club won the league by a record Super League margin of 10 points and equalled the highest points of 50. -

Leigh Centurions V WIDNES VIKINGS

Leigh Centurions v WIDNES VIKINGS SUNDAY 28TH JULY 2019 @ 4PM AB SUNDECKS 1895 CUP SEMI FINAL # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB AB SUNDECKS BECOME TITLE SPONSORS OF THE 1895 Cup FROM THE TOP Welcome to this afternoon’s AB Alex Murphy with cup 1971 It was great to see Adam Higson returning to Sundecks 1895 Cup semi-final the club and to see the way Junior Sa’u and Leigh Centurions club sponsor AB Mitch Clark have already settled in. Sundecks expanded its support of against Widnes Vikings. Rugby League by becoming title It’s a big game for both clubs and both sets of Meanwhile young Josh Simm made his Super players. I was speaking to Tony Barrow in the League debut at London last Sunday, one of sponsor of the inaugural 1895 Cup, nine Saints players in the team that day the final of which will be played at week ahead of him being our special guest this afternoon in Premier Club. that’ve played for Leigh this year. Wembley Stadium on Saturday, 24 Congratulations to Josh and thanks again for August: Tony was a key member of the 1971 all the Saints lads who have fully bought into Wembley team having played for Saints in playing for Leigh Centurions. AB Sundecks has established itself as one their 1966 success over Wigan. of the UK’s leading manufacturers and Tony was a top player in his day and was in Ryan Brierley installers of complete PVCu decking top form in the 1973-74 season and solutions to the leisure and domestic considered a shoe-in for a place on the GB markets. -

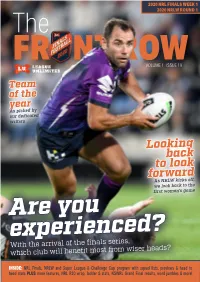

Looking Back to Look Forward

2020 NRL FINALS WEEK 1 The 2020 NRLW ROUND 1 FRONT ROW VOLUME 1 · ISSUE 19 Team of the year As picked by our dedicated writers Looking back to look forward As NRLW kicks off, we look back to the first women's game Are you experienced? With the arrival of the finals series, which club will benefit most from wiser heads? INSIDE: NRL Finals, NRLW and Super League & Challenge Cup program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats PLUS more features, NRL R20 wrap, ladder & stats, NSWRL Grand Final results, word jumbles & more! What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - ISSUE 19 Tim Costello From the editor 2 We made it! It's finals time in the NRL and there are plenty of intriguing storylines tailing into the business end of the Feature LU team of the year 3 season. Can the Roosters overcome a record loss to record Feature NRL Finals experience 4-5 a three-peat? Will Penrith set a new winning streak record to claim their third premiership? What about the evergreen Feature First women's game 6-7 Melbourne Storm - can they grab yet another title... and in Feature Salford's "private hell" 8 all likelihood top Cameron Smith's illustrious career? That and many more questions remain to be answered. Stay Feature Knights to remember 9 tuned. Word Jumbles, Birthdays 9 This week we have plenty to absorb in the pages that follow. THE WRAP · NRL Round 20 10-14 From analysis of the most Finals experience among the top eight sides, to our writers' team of the year, to a look back at Match reports 10-12 the first women's game in Australia some 99 years ago.. -

In Opposition Castleford Tigers

Round 4 vs CASTLEFORD TIGERS 22-04-21 - Kick Off 6pm at The DW Stadium Official Match Programme Free to Download #NeverGonnaStop WARRIOROFFICIAL CLUB PARTNERS 2021 We Are Warriors. CLUB HONOURS CONTACT US SUPER LEAGUE WINNERS STADIUM ADDRESS 1998, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2018 DW Stadium, Loire Drive, Wigan WN5 0UH SUPER LEAGUE GRAND FINALISTS STADIUM TELEPHONE 2000, 2001, 2003, 2014, 2015, 2020 01942 774000 SUPER LEAGUE LEADERS OFFICE ADDRESS 1998, 2000 2010, 2012, 2020 (League Leaders Shield) Robin Park Arena, Loire Drive, Wigan WN5 0UH WORLD CLUB CHALLENGE WINNERS OFFICE TELEPHONE 1987/88, 1991/92, 1993/94, 2017 01942 762888 CHAMPIONSHIP WINNERS TICKET OFFICE TELEPHONE 1908/09, 1921/22, 1925/26, 1933/34, 1945/46, 1946/47, 01942 762875 (temporary number, weekdays 10am-4pm) 1949/50, 1951/52, 1959/60, 1986/87, 1989/90, 1990/91, 1991/92, 1992/93, 1993/94, 1994/95, WEBSITE 1995/96 (Centenary Champions) www.wiganwarriors.com PREMIERSHIP TROPHY WINNERS E-MAIL [email protected] 1987, 1992, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997 TWITTER CHALLENGE CUP WINNERS @wiganwarriorsrl 1923/24, 1928/29, 1947/48, 1950/51, 1957/58, 1958/59, FACEBOOK 1964/65, 1984/85, 1987/88, 1988/89, 1989/90, 1990/91, www.facebook.com/wiganwarriorsrl 1991/92, 1992/93, 1993/94, 1994/95, 2002, 2011, 2013 INSTAGRAM CHARITY SHIELD WINNERS @wiganwarriorsrl 1985/86, 1987/88, 1991/92, 1995/96 REGAL TROPHY WINNERS CLUB OFFICIALS 1982/83, 1985/86, 1986/87, 1988/89, 1989/90, 1992/93, CHAIRMAN AND OWNER 1994/95, 1995/96 Ian Lenagan LANCASHIRE CUP WINNERS NON-EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS 1905/06, 1908/09, 1909/10, -

LEIGH CENTURIONS V FEATHERSTONE ROVERS SUNDAY 27Th APRIL 2014 at LEIGH SPORTS VILLAGE • KICK OFF 3PM

TETLEY’S CHALLENGE CUP FIFTH ROUND LEIGH CENTURIONS v FEATHERSTONE ROVERS SUNDAY 27th APRIL 2014 AT LEIGH SPORTS VILLAGE • KICK OFF 3PM Matchday Host Matchball Sponsor ISSUE 6 PRICE £2.50 HONOURS Championship Winners: 1905-06 Cover Star: FROM THE TOP Gregg McNally Division One Champions: shows his 1981-82 delight at Division Two Champions: By Chairman JOHN RODDY scoring his 1977-78, 1985-86, 1988-89 second try Challenge Cup Winners: against the 1920-21, 1970-71 ay I first of all welcome to Leigh strength to strength under the Lions. MSports Village, the home of dynamic leadership of Jason Lancashire Cup Winners: Leigh Centurions RLFC, the 1952-53, 1955-56, 1970-71, 1981-82 Donohue. It is wonderful to see so Directors, Officials, Players and many past players enjoying visiting BBC2 Floodlit Trophy: Supporters of Featherstone Rovers, LSV and supporting the team. Last WHO’S WHO 1969-70, 1972-73 for this eagerly awaited Tetley’s Friday I had the pleasure of At Leigh Centurions Promotion To Top Division Challenge Cup Fifth Round- tie. meeting Paul Topping and Mark achieved(Not as Champions): Sheals who were both very Hon Life President Statistician 1963-64, 1975-76, 1991-92 Both teams are currently in fine form, sitting at the top of the Kingstone Press Championship and I expect that we will see a impressed by our facilities and the Mr Tommy Sale MBE Mr Cliff Sumner Other Promotion season: close game this afternoon with all the magic and atmosphere that display of the current Centurions Paul Topping and Mark Sheals Hon Vice President Kit men 1997 (Division 3 to Division 2) the Challenge Cup brings to Rugby League. -

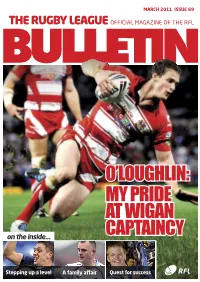

Bulletin 69.Indd

MARCH 2011 ISSUE 69 THE RUGBY LEAGUE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE RFL O’LOUGHLIN: MY PRIDE AT WIGAN on the inside… CAPTAINCY Stepping up a level A family affair Quest for success RAISE FUNDS FOR YOUR CLUB 14 Stepping up a level CARNEGIE CHALLENGE CUP FINAL 27th AUGUST 2011 £31 ticket for £26 on the upgrade offer - for every 50 sold your club will get a return of £250 or CONTENTS £51 ticket for £41 on the upgrade 5 Media Matters offer - for every 50 sold your club 6 The best of the best will get a return of £500 8 Managing the Lions plus 9 Southern expansion ticket and hotel offers 10 Destination Wembley offering £2000 cashback 16 O’Loughlin: 12 New Wheelchair structure My pride at Wigan 22 A family 20 A call to arms captaincy affair 21 Summer lovin’ 24 Higginshaw’s big idea 26 Grassroots flourishing 30 Academy 2011 Castleford Lock Lane Hull East Leigh East Hull Embassy MARCH 2011 ISSUE 69 THE RUGBY LEAGUE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE RFL Outwood Grange Halifax RLFC Myton Warriors Crigglestone All Blacks Catterick Garrison LIMITED O’LOUGHLIN: AVAILABILITY MY PRIDE Get in quick! AT WIGAN on the inside… CAPTAINCY Milnrow Cobras Holderness Vikings Stepping up a level A family affair Quest for success for more information contact 27 Quest for Ray Tennant success T: 07595 520 338 ray.tennant@rfl.uk.com Bev Coleman T: 07595 520 578 bev.coleman@rfl.uk.com Ryburn Valley High School Spen Valley INSIDE THIS ISSUE MEDIA MATTERS .... with Neil Barraclough Welcome to the first Rugby League Bulletin daylight second, and everything else well of 2011 ... -

The Front Row Forums Australia’S Biggest Rugby League Discussion Boards

2020 NRL FINALS WEEK 2 2020 NRLW ROUND 2 The FRONT ROWVOLUME 1 · ISSUE 20 Class of 2020 This year's rookies chose an interesting year to break out! Triple treat Hat-trick hero Tamika Upton is ready to help the Broncos to an historic NRLW three-peat INSIDE: NRL Finals, NRLW and Super League program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats PLUS more features, NRL Finals Week 1 & #NRLW R1 wrap, crossword, word jumbles & more! THE FRONT ROW FORUMS AUSTRALIA’S BIGGEST RUGBY LEAGUE DISCUSSION BOARDS forums.leagueunlimited.com THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 1 ISSUE 20 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - ISSUE 20 Tim Costello From the editor 3 For a season that prided itself on unpredictability, the first week of the NRL Finals threw up a fairly predictable set of Feature 2020 Rookie Class 4-5 results. The top four teams got the choccies and the top two Feature Tamika Upton 6-7 have set their dates for preliminary final action. The result ensured the Storm would head to their sixth consecutive THE WRAP · NRL Finals & NRLW 8-11 year of Preliminary Final appearances, while the Panthers Match reports 8-10 showed why they're a genuine title contender with a strong performance against a never-say-die Roosters. The Scoresheet 9 question now - will this weekend's semis throw up similarly predictable winners or is a spanner about to be thrown in Birthdays 10 the works? Finals roadmap, Match Review, Word Jumbles 11 Turning focus to this week's magazine and we have a GAME DAY 13 number of great feature pieces this week - Rob Crosby FRI NRL SF1 - Roosters v Raiders 14-15 has identified the key contenders for 2020's Rookie of the Year as we look at the whole class of NRL newbies in this SAT NRL SF2 - Eels v Rabbitohs 16-17 bizarre year; while Paul Jobber talks to Broncos hat-trick FRI NRLW R2 - Warriors v Roosters 18-19 hero Tamika Upton after her side picked up an opening round win in the NRLW on the weekend. -

The Castleford Tigers

CASTLEFORD TIGERS #COYF 2018 CORPORATE BROCHURE WWW.CASTLEFORDTIGERS.COM THE CASTLEFORD TIGERS Castleford Tigers compete in the Betfred Super League, the elite professional European Rugby League Competition. For 92 years Castleford Tigers have called the Mend-A-Hose Jungle on Wheldon Road it’s home and for 92 years the club has played an essential part within the local community. Castleford fans are loud, proud and passionate about this great club, and if you think of Castleford you immediately think of Castleford Tigers! In 2017 Castleford Tigers made history, winning the League Leaders Shield for the first time in the clubs 91 year history, in classy style, lifting the trophy in front of a packed house at the Mend-A-Hose Jungle and live on Sky Sports. The Tigers also reached the Betfred Super League Grand Final for the first time in the clubs Super League history. Game days at the Mend-A-Hose Jungle are intense and Castleford Tigers certainly like to put on a show and entertain their fans! We’d love for your brand to join the Tigers family and join us on our journey as the club continues to grow. CASTLEFORD TIGERS #COYF 2018 CORPORATE BROCHURE WWW.CASTLEFORDTIGERS.COM GET CONNECTED Castleford Tigers prides itself on a thriving social engagement, which is purely organic. Our digital footprint reaches all corners of the globe as our website has now been viewed in over 180 countries. Average Weekly Views 66,959 www.castlefordtigers.com Facebook Likes 63,728 CastlefordTigers Twitter Followers 46,510 @CTRLFC Website views based on average weekly visits between February 27th 2017 and February 27th 2018. -

The O Cial Magazine of Rugby League Cares Summer/Autumn 2017 Specialist Insurance for Sports Professionals

The O cial Magazine of Rugby League Cares Summer/Autumn 2017 Specialist Insurance For Sports Professionals For excellent rates on your car and home insurance...call us today! “QUOTE RUGBY LEAGUE CARES” @AllSportInsure +44 (0)1803 659121 Visit: www.allsportinsurance.co.uk elcome to this summer edition of One in, All In, our new- styled twice-yearly newsletter. W The feedback we received on the new format was fantastic and we hope you enjoy catching up on the work of Rugby League Cares and its supporters that is detailed in this magazine. It continues to be an extremely busy time for the RL Cares team and since our last newsletter in January the charity has moved forward in a variety of ways. In April, we launched our new men’s mental health and wellbeing programme, O oad. The programme is funded by the Big Lottery and is a unique collaboration between Rugby League Cares, State of Mind and the Warrington Wolves, Widnes Vikings and Salford Red Devils club foundations. We are delighted with the progress being made on the programme, which is being expertly managed by a new member of the RL Cares team, Emma Goldsmith. Emma’s background is in public health and there are some very exciting plans being developed to extend and enhance our fan-focused health services. Our player welfare programme has received a signifi cant boost with former Leeds Rhinos and Great Britain international WELCOME Keith Senior joining the team on a concepts and framework for what the new amazing to be able to share this story with part-time basis. -

LEIGH CENTURIONS V FEATHERSTONE ROVERS FRIDAY, 8Th August 2014 at LEIGH SPORTS VILLAGE • KICK OFF 8.00PM

aa LEIGH v FEATHERSTONE 40pp_Layout 1 05/08/2014 16:24 Page 1 KINGSTONE PRESS CHAMPIONSHIP ROUND 23 LEIGH CENTURIONS v FEATHERSTONE ROVERS FRIDAY, 8th August 2014 AT LEIGH SPORTS VILLAGE • KICK OFF 8.00PM Match Sponsor Match Ball Sponsor Programme Sponsor ISSUE 13 PRICE £2.50 aa LEIGH v FEATHERSTONE 40pp_Layout 1 05/08/2014 16:24 Page 2 HONOURS Championship Winners: 1905-06 Division One Champions: 1981-82 Division Two Champions: 1977-78, 1985-86, 1988-89 Cover Star: Tom Armstrong Challenge Cup Winners: looks to evade 1920-21, 1970-71 Brendan Rawlins Lancashire Cup Winners: 1952-53, 1955-56, 1970-71, 1981-82 BBC2 Floodlit Trophy: WHO’S WHO 1969-70, 1972-73 At Leigh Centurions Promotion To Top Division achieved(Not as Champions): Hon Life President Kit men 1963-64, 1975-76, 1991-92 Mr Tommy Sale MBE Mr Frank Taylor Other Promotion season: Hon Vice President Mr Sean Fairhurst 1997 (Division 3 to Division 2) Mr Tommy Mather Mr Andy Burnham MP Northern Ford Minor Premiership Hon Life Members Under 20’s Coach Winners: 2001 Mr Paul Anderson Mr Brian Bowman Trans-Pennine Cup Winners: 2001 Mr Tommy Coleman Under 20’s Assistant Mr Frank Taylor Mr Steve Mayo Arriva Trains Cup Winners: 2004 Mr John Massey Conditioner LHF National League 1 Champions: Board of Management Mr Dan Ogden 2004 Mr Michael Norris - Chairman Physiotherapists LHF National League 1 Grand Final Mr Derek Beaumont Ms Emma Fletcher Winners: 2004 Mr Andy Mazey Ms Hannah Lloyd Northern Rail Cup Winners: Mr Alan Platt Mr John Stopford (Under 20's) 2006, 2011, 2013 Mr Steve Openshaw -

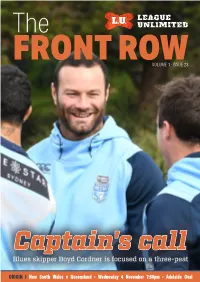

Blues Skipper Boyd Cordner Is Focused on a Three-Peat

The FRONT ROWVOLUME 1 · ISSUE 23 Captain's call Blues skipper Boyd Cordner is focused on a three-peat ORIGIN I New South Wales v Queensland - Wednesday 4 November 7:50pm - Adelaide Oval THE FRONT ROW FORUMS AUSTRALIA’S BIGGEST RUGBY LEAGUE DISCUSSION BOARDS forums.leagueunlimited.com THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 1 ISSUE 23 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - ISSUE 23 Tim Costello From the editor 3 Congratulations to the Melbourne Storm, overcoming a mountain of obstacles to claim their fourth premiership in Feature Boyd Cordner 4-5 their 23 seasons. They downed a Penrith side last Sunday in what was a riverting second half of a Grand Final. Feature Origin 2020 style 6 It was a Grand Final Day for the seasoned victors - Brisbane Feature Greatest Dynasties 7 claimed their third straight NRLW title as well, although the Feature League in Lockdown 8-9 Roosters certainly made the work for it. NRL Grand Final Review 10 Focus now shifts to the big stage of Origin. New South Wales are on the hunt for their third straight series win after Birthdays, Word Jumbles 10 nearly a decade in the wilderness. Queensland are almost NRLW Grand Final Review 11 in a rebuilding phase following the departures of key spine players and will need a big effort in 2020 to overcome the GAME DAY - State of Origin 1 12-13 odds. 2020 NRL & NRLW Draw 14-15 This week's edition looks at Origin through the eyes of NSW GAME DAY - Super League R20 16 skipper Boyd Cordner as well as a bit of perspective on what to expect from this series from our Origin columnist SUN Wakefield v Leeds 16-17 Rick Edgerton. -

Harnessing Socio-Cultural Constraints on Athlete

Harnessing Socio-cultural Constraints on Journal of Expertise 2018. Vol. 1(1) Athlete Development to Create a Form of Life © 2018. The authors license this article under the terms of the 1 2 3 Creative Commons Martyn Rothwell , Keith Davids , and Joseph Stone Attribution 3.0 License. 1, 2 3 Center for Sports Engineering Research, Sheffield Hallam University; Academy for Sport & ISSN 2573-2773 Physical Activity, Sheffield Hallam University Correspondence: Martyn Rothwell, [email protected], ph: 0114 225 3989 Abstract The role of task constraints manipulation in pedagogical practice has received considerable attention in recent years, although there has been little focus on the role of socio-cultural constraints on an athlete's development to elite performance. Here, we aim to integrate ideas from a range of scientific sub-disciplines to consider why certain behaviors and cultures (socio-cultural constraints) may exist in sport performance and coaching. Using recent conceptualizations of affordances in ecological dynamics, we explore how socio-cultural constraints may influence an athlete's development and relationship with a performance context. We also highlight how workplace practices eminating from the industrialization of the nineteenth century in countries such as the UK may have influenced coaching practice and organizational behaviors from that time on. In particular, features such as strict work regimes and rigid role specification may have reduced personal autonomy, de-skilled performers, and induced a “body as machine” philosophy within sporting organizations. These traits could be considered counter to expert performance in sports where creativity and adaptive decision-making are important skills for athletes to possess.