Gordon & Woburn Squares

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undergraduate Prospectus 2021 Entry

Undergraduate 2021 Entry Prospectus Image captions p15 p30–31 p44 p56–57 – The Marmor Homericum, located in the – Bornean orangutan. Courtesy of USO – UCL alumnus, Christopher Nolan. Courtesy – Students collecting beetles to quantify – Students create a bespoke programme South Cloisters of the Wilkins Building, depicts Homer reciting the Iliad to the – Saltburn Mine water treatment scheme. of Kirsten Holst their dispersion on a beach at Atlanterra, incorporating both arts and science and credits accompaniment of a lyre. Courtesy Courtesy of Onya McCausland – Recent graduates celebrating at their Spain with a European mantis, Mantis subjects. Courtesy of Mat Wright religiosa, in the foreground. Courtesy of Mat Wright – Community mappers holding the drone that graduation ceremony. Courtesy of John – There are a number of study spaces of UCL Life Sciences Front cover captured the point clouds and aerial images Moloney Photography on campus, including the JBS Haldane p71 – Students in a UCL laboratory. Study Hub. Courtesy of Mat Wright – UCL Portico. Courtesy of Matt Clayton of their settlements on the peripheral slopes – Students in a Hungarian language class p32–33 Courtesy of Mat Wright of José Carlos Mariátegui in Lima, Peru. – The Arts and Sciences Common Room – one of ten languages taught by the UCL Inside front cover Courtesy of Rita Lambert – Our Student Ambassador team help out in Malet Place. The mural on the wall is p45 School of Slavonic and East European at events like Open Days and Graduation. a commissioned illustration for the UCL St Paul’s River – Aerial photograph showing UCL’s location – Prosthetic hand. Courtesy of UCL Studies. -

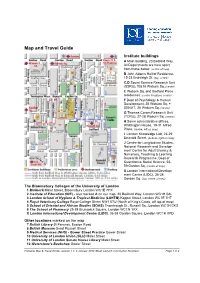

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

BCLA), Birkbeck Gender and Sexuality (Bigs), the Birkbeck Institute for Social Research (BISR), and Mapping Maternal Subjectivities, Identities and Ethics (Mamsie

The Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities in collaboration with British Comparative Literature Association (BCLA), Birkbeck Gender and Sexuality (BiGS), the Birkbeck Institute for Social Research (BISR), and Mapping Maternal Subjectivities, Identities and Ethics (MaMSIE) Birkbeck, University of London, London WC1E 7JL | 1 Room Key: CLO - Clore Management Centre, Torrington Square, London WC1E 7JL MAL – Birkbeck Main building, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX, entrance off Torrington Square. Cinema – 43, Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PD Download a map showing the location of all the buildings Wi-fi: Free wi-fi access is available. To access wi-fi connect to the Birkbeck-Wam and then open a browser. The login page should automatically load. Then click 'Guest Access' and enter either of the following the login details. Guest Username: fem220617 Guest Password: utNpXU Thursday 22 June 17.30 – 18.00 Registration CLO B01 Foyer 18.00 – 19.30 Keynote lecture CLO Room B01 Unspeakable Acts: Live streaming in MAL The Tongues of M. NourbeSe Philip Room B35 M. NourbeSe Philip (Poet, Thinker, Activist) Chair: Marina Warner (Birkbeck, University of London) Followed by a book-signing with M. NourbeSe Philip Friday 23 June 10.00 – 11.30 Parallel panel session 1 MAL Room B35 Trouble for girls: Growing up in rape culture Katherine Angel (Birkbeck, University of London) Holly Bourne (Author) Marianne Forsey (Brook Advisory) Catherine Johnson (Author, Screenwriter) Chair: Julia Bell (Birkbeck, University of London) | 2 10.00 – 11.30 Parallel panel session 2 CLO -

Connaught Hall Residents’ Handbook 2010 / 2011 SESSION

abcdef University of London Connaught Hall Residents’ HANDBOOK 2010 / 2011 SESSION www.connaught-hall.org.uk Connaught Hall Connaught Hall is a fully catered University of London intercollegiate hall of residence for full-time students from all the colleges and institutes of the University. We aim to provide a secure, supportive, friendly, and tolerant environment in which our residents can study, relax, and socialise. Connaught Hall was established in 1919 by hrh Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn — the third son of Queen Victoria — at 18 Torrington Square as a private hall of residence for male students, a memorial to the Duchess of Connaught, who died in 1917. The Duke gave the Hall to the University of London in 1928, but it was not until 1961 that Connaught Hall moved out of Torrington Square to its present location in Tavistock Square: a converted Georgian terrace with a Grade II listed façade. Women have been admitted since 2001. One of eight intercollegiate halls of residence, Connaught Hall now accommodates 226 students. There is an even mix of men and women and a great diversity of cultural and social backgrounds. Most residents are first-year undergraduates, with around 20% being allowed to return for a second year at the Warden’s discretion; approximately 10% are postgraduates, and about a third are overseas students. Most accommodation is in single study-bedrooms; there is room for ten students in twin rooms. There is a washbasin in every room, but toilet and shower facilities are all shared. Every room has telephone and internet connections. -

MAP 1 of 4 - TORRINGTON PLACE to TAVISTOCK PLACE: 107 to 113 to 107 QUEEN's LOCATION and EFFECT58 of PROPOSED TRAFFIC ORDER YARD

FB A A 82 80 76 GOWER STREET GOWER STREET 73 85 77 107 to 113 to 107 97 105 87 88 to 96 86 80 74 72 68 CHENIES MEWS CHENIES MEWS TORRINGTON PLACE RIDGMOUNT GARDENS 67 51 49 to 63 to 49 103 77 to 89 to 77 64 to 76 to 64 Gordon Mansions to 90 31 to 75 58 46 HUNTLEY STREETHUNTLEY STREET HUNTLEY STREET HUNTLEY STREET BB LOOK RIGHT LOOK 1 to 6 to 1 Royal Ear Hospital 49 to 43 LOOK RIGHT Marlborough Howard Pearson (Univ College Hospital) Univ College Gordon Mansions BB Arms 36 32 36 1 to 12 to 1 House12 to 1 House Hospital Union 9 to 1 (PH) 1 to 30 28 26 24 26 MAP 1 of 4 - TORRINGTON PLACE TO TAVISTOCK PLACE: LOCATION AND EFFECT OF PROPOSED TRAFFIC ORDER 20 LOADING ONLY LOADING No left turn except for cyclists Direction of travel No right turn except for cyclists 22 Planet Organic Mullard House 179a 1 to 19 YARD Philips House QUEEN'S 180 16 to 2 to TORRINGTON PLACE 177 PH to 182 178 179 183 Bank Brook House 188 189 to 190 191 to 199 TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD 27.4m Taxi rank No waiting or loading at any time Double yellow line (no waiting at any time) Single yellow line (no waiting during restricted period) Orca Loading bay N 88 to 94 to 88 80 to 85 to 80 D Fn Note: Signs giving effect to earlier traffic orders are generally not shown Legend: TCBs 79 Bank GORDON SQUARE Gordon Square Garden FB GORDON SQUARE N 15 Petrie MAP 2 of 4 - TORRINGTON PLACE TO TAVISTOCK PLACE: Museum LOCATION AND EFFECT OF PROPOSED TRAFFIC ORDER25.1m 14 47 The Cloisters 1 to 5 GORDON SQUARE A GORDON SQUARE B Church of Christ The King 1 to 3 to 1 LEFT TURN MALET PLACE 53 4 -

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 18 April 2011 i) CONTENTS PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 0 Purpose of the Appraisal ............................................................................................................ 2 Designation................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 4 3.0 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST........................................................................................ 5 Context and Evolution................................................................................................................ 5 Spatial Character and Views ...................................................................................................... 6 Building Typology and Form....................................................................................................... 8 Prevalent and Traditional Building Materials ............................................................................ 10 Characteristic Details................................................................................................................ 10 Landscape and Public Realm.................................................................................................. -

Newsletter C

RAPH OG IC P A O L T S O N Newsletter C O Number 86 I D E N May 2018 T Y O L Marylebone seen from Centrepoint, with All Saints Margaret Street in the centre. Historic England Archives Contents Obituary: ‘A Place in the Sun’: topography through Francis Sheppard, Gavin Stamp, Iain Bain.... p.2 insurance policies by Isobel Watson .............. p.6 Notes and News ............................................ p.3 Parishes, Wards, Precincts and Liberties. Solving Exhibitions and Events ................................ p.3 a topographical puzzle by Ian Doolittle .......... p.9 Out and About .............................................. p.4 Preserving London’s Film Heritage at the British Circumspice ...................................... p.4 & p.14 Film Institute by Christopher Trowell .......... p.10 Changing London.......................................... p.5 Lots Road power station transformed A map of Tudor London by David Crawford ...................................... p.11 by Caroline Barron and Vanessa Harding...... p.5 Reviews and Bookshop Corner .............. p.14-19 Obituary Marylebone. The result was published as Local Government in St Marylebone 1688-1835, Francis Henry Wollaston Sheppard published 1958. Inspired by the Edwardian 10 September 1921- 22 January 2018 scholarship of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, it is a most readable and lucid study of English local Between 1954 and his retirement in 1983 Francis government. Sheppard produced no fewer than 16 volumes of In the 1950s interest in urban architecture and The Survey of London, transforming what had planning stopped short at the Victorian period. been a sporadic and selective record of London’s Sheppard was aware of the need to go further, historic buildings, area by area, into a model of and began to do so in his first volume of the urban topographical writing, rich in content, reanimated Survey, on south Lambeth (1956). -

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and Their Origins

CAMDEN STREET NAMES and their origins © David A. Hayes and Camden History Society, 2020 Introduction Listed alphabetically are In 1853, in London as a whole, there were o all present-day street names in, or partly 25 Albert Streets, 25 Victoria, 37 King, 27 Queen, within, the London Borough of Camden 22 Princes, 17 Duke, 34 York and 23 Gloucester (created in 1965); Streets; not to mention the countless similarly named Places, Roads, Squares, Terraces, Lanes, o abolished names of streets, terraces, Walks, Courts, Alleys, Mews, Yards, Rents, Rows, alleyways, courts, yards and mews, which Gardens and Buildings. have existed since c.1800 in the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn and St Encouraged by the General Post Office, a street Pancras (formed in 1900) or the civil renaming scheme was started in 1857 by the parishes they replaced; newly-formed Metropolitan Board of Works o some named footpaths. (MBW), and administered by its ‘Street Nomenclature Office’. The project was continued Under each heading, extant street names are after 1889 under its successor body, the London itemised first, in bold face. These are followed, in County Council (LCC), with a final spate of name normal type, by names superseded through changes in 1936-39. renaming, and those of wholly vanished streets. Key to symbols used: The naming of streets → renamed as …, with the new name ← renamed from …, with the old Early street names would be chosen by the name and year of renaming if known developer or builder, or the owner of the land. Since the mid-19th century, names have required Many roads were initially lined by individually local-authority approval, initially from parish named Terraces, Rows or Places, with houses Vestries, and then from the Metropolitan Board of numbered within them. -

Bloomsbury in Nineteenth-Century Fiction: Some Quotations Compiled by Matt Ingleby and Deborah Colville

Bloomsbury in Nineteenth-Century Fiction: Some Quotations compiled by Matt Ingleby and Deborah Colville From Theodore Hook’s Sayings and Doings (1824) One day, some week perhaps after the dismissal of Rushbrook, Henry was dining with the Meadowses, who were going to Mrs. Saddington’s assembly in Russell-square. It may be advantageously observed here, that this lady was the dashing wife of the eminent banker, whose acceptance to a bill due the next day my hero had in his pocket. To this party Mrs. Meadows pressed him to accompany them, never forgetting, as I hope my readers never will, that he, the said Henry Merton, Esq. held an appointment under Government of some four-and-twenty hundred pounds per annum, and was therefore a more suitable and agreeable companion for herself and daughter, than when he was “a single gentleman three months ago,” with no estate save that, which lay under his hat, and no income except that derivable from property entirely at the disposal of his father. Henry at first objected; but never having seen much of that part of the town in which this semi-fashionable lived, and desirous of ascertaining how people “make it out” in the recesses of Bloomsbury and the wilds of Guildford Street, and feeling that “all the world to him” would be there, at length agreed to go, and accordingly proceeded with the ladies in their carriage through Oxford-street, St. Giles’s, Tottenham-court-road and so past Dyott-street, and the British Museum, to the remote scene of gaiety, which they, however, reached in perfect safety. -

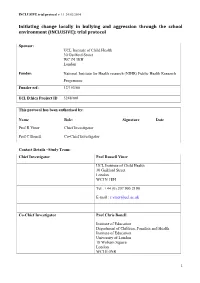

Initiating Change Locally in Bullying and Aggression Through the School Environment (INCLUSIVE): Trial Protocol

INCLUSIVE trial protocol v 1.1 24/02/2014 Initiating change locally in bullying and aggression through the school environment (INCLUSIVE): trial protocol Sponsor: UCL Institute of Child Health 30 Guilford Street WC1N 1EH London Funder: National Institute for Health research (NIHR) Public Health Research Programme Funder ref: 12/153/60 UCL Ethics Project ID 5248/001 This protocol has been authorised by: Name Role: Signature Date Prof R Viner Chief Investigator Prof C Bonell Co-Chief Investigator Contact Details –Study Team: Chief Investigator Prof Russell Viner UCL Institute of Child Health 30 Guilford Street London WC1N 1EH Tel : +44 (0) 207 905 2190 E-mail : [email protected] Co-Chief Investigator Prof Chris Bonell Institute of Education Department of Children, Families and Health Institute of Education University of London 18 Woburn Square London WC1H 0NR 1 INCLUSIVE trial protocol v 1.1 24/02/2014 +44 (0)20 7612 6731 E-mail: [email protected] TRIAL MANAGER Anne Mathiot 30 Guilford Street London WC1N 1EH Tel : +44 (0) 207 905 2772 Fax : +44 (0) 207 905 2834 E-mail : [email protected] DATA MANAGER Joanna Sturgess Clinical Trial Units London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Room 186, Keppel Street WC1E 7HT London +44 (0)20 7958 8122 +44 (0) 20 7299 4663 [email protected] Please contact the Study Manager for general queries and supply of trial/study documentation 2 INCLUSIVE trial protocol v 1.1 24/02/2014 Table of Content: Aim page 4 Research objective milestones page 4 Design page 4 Study population page 4 Inclusion/Exclusion -

Web Annex B: Health Professionals' Mobile Digital Education

WHO Guideline: Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health Systems Strengthening Web Annex B: Health professionals’ mobile digital education: a systematic review of factors influencing implementation and adoption (unpublished review) Link to pre-print for publication: http://preprints.jmir.org/preprint/12895 Lall, P., Rees, R.W.1, Law, G.C.Y., Dunleavy, G.2, Cotic, Z., Car, J.2,3 1Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), Social Science Research Unit, Department of Social Science, UCL Institute of Education, University College London, 18 Woburn Square, London, WCIH0NR, UK; 2Centre of Population Health Services (CePHeS), Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, 11 Mandalay Road, Singapore 308232; 3Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, UK Abstract Background In the past five decades, electronic learning has increasingly been used in health professional education. Mobile learning (mLearning), an emerging form of educational technology using mobile devices, has been used to supplement learning outcomes through enabling conversations, the sharing of information and knowledge with other learners; and, aiding support from peers and instructors regardless of geographic distance. Objectives This review synthesises findings from qualitative or mixed methods studies to provide insight into factors facilitating or hindering implementation of mLearning strategies for medical and nursing education. Methods A systematic search was conducted across a range of databases. Studies were selected on the basis that they were examining mLearning in medical and nursing education, employed a mixed methods or qualitative approach, and were published in English after 1995. Findings were synthesised using a framework synthesis approach. -

Map 1 UOL.PDF

Euston University of London buildings Warren Street 1 Senate House British EUSTON RD Library 2 Stewart House 3 Institute of Advanced Legal Studies (& Library) Euston EUSTON RD Square King’s Cross 4 University of London Union (ULU) St. Pancras GOWER PL 5 The Warburg Institute (& Library) UPPER WOBURN PL University of London Colleges 6 Birkbeck University of London GOWER ST GOWER CARTWRIGHT GARDENS CARTWRIGHT HASTINGS ST 7 Institute of Education University of London 8 The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine 15 JUDD ST JUDD 9 The School of Oriental and African Studies 10 UCL 11 Garden TAVISTOCK SQ TAVISTOCK GORDON SQ GORDON Halls Colleges below not shown - The Central School of Speech and Drama (NW3 3HY) 13 - Courtauld Institute of Art (WC2R 0RN) 17 LEIGH ST - Goldsmiths University of London (SE14 6NW) - Heythrop College (W8 5HN) 10 14 - The Institute of Cancer Research (SW7 3RP) L TAVISTOCK PL - King’s College London (WC2R 2LS) P Goodge G Street N - London Business School (NW1 4SA) BY MARCHMONT ST MARCHMONT - The London School of Economics & Political Science (WC2A 2AE) 5 20 ST HERBRAND MALET ST GOWER ST 19 - Queen Mary University of London (E1 4NS) 4 7 How to find us 12 ST HUNTER - Royal Academy of Music (NW1 5HT) - Royal Holloway University of London (TW20 0EX) Brunswick Centre - The Royal Veterinary College (NW1 0UT) - 6 9 - St George’s University of London (SW17 ORE) 3 University student halls 1 Senate House 8 11 Canterbury Hall Malet Street see map 2 London, WC1E 7HU Tel: (020) 7862 8000 12 College Hall RUSSELL SQ 13 Commonwealth Hall 14 Connaught Hall STORE ST Russell 1 Square 15 Hughes Parry Hall 18 2 16 16 International Hall Halls below not shown GUILFORD ST - Lillian Penson Hall (W2 1TT) Map MONTAGUE PL MONTAGUE ST N - Nutford House (W1H 5UL) University garden squares W E 17 Gordon Square British Museum 18 Malet Street Gardens 19 Torrington Square s 20 Woburn Square Holborn Tottenham Court Road May 2012.