Bloomsbury in Nineteenth-Century Fiction: Some Quotations Compiled by Matt Ingleby and Deborah Colville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloomsbury Scientists Ii Iii

i Bloomsbury Scientists ii iii Bloomsbury Scientists Science and Art in the Wake of Darwin Michael Boulter iv First published in 2017 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ ucl- press Text © Michael Boulter, 2017 Images courtesy of Michael Boulter, 2017 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Michael Boulter, Bloomsbury Scientists. London, UCL Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350045 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 006- 9 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 005- 2 (pbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 004- 5 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 007- 6 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 008- 3 (mobi) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 009- 0 (html) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787350045 v In memory of W. G. Chaloner FRS, 1928– 2016, lecturer in palaeobotany at UCL, 1956– 72 vi vii Acknowledgements My old writing style was strongly controlled by the measured precision of my scientific discipline, evolutionary biology. It was a habit that I tried to break while working on this project, with its speculations and opinions, let alone dubious data. But my old practices of scientific rigour intentionally stopped personalities and feeling showing through. -

Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage

Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage London, WC1 Mixed-Use Investment Opportunity www.geraldeve.com Red Lion Street & Lamb's Conduit Passage, WC1 Investment summary • Freehold • Midtown public house, retail unit and residential flat • 3,640 sq ft (338.16 sq m) GIA of accommodation • WAULT of 8.1 years unexpired • Total passing rent of £106,700 pa • Seeking offers in excess of £1,850,000 subject to contract and exclusive of VAT • A purchase at this price would reflect a net initial yield of 5.44%, assuming purchaser’s costs of 6.23% www.geraldeve.com 44 Red Lion Street & Lamb’s Conduit Passage, WC1 Midtown 44 Red Lion Street & Lamb’s Conduit Passage is located in an enviable position within the heart of London’s Midtown. Midtown offers excellent connectivity to the West End, City of London and King’s Cross, appealing to an eclectic range of occupiers. The location is typically regarded as a hub for the legal profession, given the proximity of the Royal Courts of Justice and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but has a diverse occupier base including, tech, media, banking and professional firms. The area is also home to several internationally renowned educational institutions such as UCL, King’s College London, London School of Economics and the University of Arts, London. The surrounding area attracts a range of occupiers, visitors and tourists with the Dolphin Tavern being a named location on several Midtown walking tours. The appeal of the location is derived in part from the excellent transport links but also the diverse and exciting range of local amenities and attractions on offer, including The British Museum, Somerset House, the Hoxton Hotel, The Espresso Room and the Rosewood Hotel. -

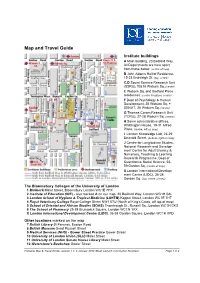

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

Design and Access Statement

New Student Centre Design and Access Statement June 2015 UCL - New Student Centre Design and Access Statement June 2015 Contributors: Client Team UCL Estates Architect Nicholas Hare Architects Project Manager Mace Energy and Sustainability Expedition Services Engineer BDP Structural and Civil Engineer Curtins Landscape Architect Colour UDL Cost Manager Aecom CDM Coordinator Faithful & Gould Planning Consultant Deloitte Lighting BDP Acoustics BDP Fire Engineering Arup Note: this report has been formatted as a double-sided A3 document. CONTENTS DESIGN ACCESS 1. INTRODUCTION 10. THE ACCESS STATEMENT Project background and objectives Access requirements for the users Statement of intent 2. SITE CONTEXT - THE BLOOMSBURY MASTERPLAN Sources of guidance The UCL masterplan Access consultations Planning context 11. SITE ACCESS 3. RESPONSE TO CONSULTATIONS Pedestrian access Access for cyclists 4. THE BRIEF Access for cars and emergency vehicles The aspirational brief Servicing access Building function Access 12. USING THE BUILDING Building entrances 5. SITE CONTEXT Reception/lobby areas Conservation area context Horizontal movement The site Vertical movement Means of escape 6. INITIAL RESPONSE TO THE SITE Building accommodation Internal doors 7. PROPOSALS Fixtures and fittings Use and amount Information and signage Routes and levels External connections Scale and form Roofscape Materials Internal arrangement External areas 8. INTERFACE WITH EXISTING BUILDINGS 9. SUSTAINABILITY UCL New Student Centre - Design and Access Statement June 2015 1 Aerial view from the north with the site highlighted in red DESIGN 1. INTRODUCTION PROJECT BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES The purpose of a Design and Access Statement is to set out the “The vision is to make UCL the most exciting university in the world at thinking that has resulted in the design submitted in the planning which to study and work. -

Woburn Place, Bloomsbury, WC1H £365000

Bloomsbury 26 Museum Street London WC1A 1JU Tel: 020 7291 0650 [email protected] Woburn Place, Bloomsbury, WC1H £365,000 - Leasehold Studio, 1 Bathroom Preliminary Details *** Offers in excess of £365,000*** A first floor studio apartment located moments from Russell Square station and Bloomsburys popular Brunswick centre, the property itself benefits from a separate kitchen, bathroom and fitted storage space in the entrance hall, the studio room offers a feature bay window enjoying floods of natural light, there is also fitted storage units. The block provides a secure entry system, full porter service, lifts and residents enjoy the inclusion of heating and hot water supply within the annual service charge. Key Features • Studio apartment • First floor • Separate kitchen and bathroom • 24 Porter service • Moments from Kings Cross St Pancras and Russell Square • Lifts Stations • A minute walk to Brunswick centre • Wood flooring Bloomsbury | 26 Museum Street, London, WC1A 1JU | Tel: 020 7291 0650 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview Blessed with gardens and squares and encompassing the capital's bastions of law, education and medicine, Bloomsbury has undisputed appeal. With shopping on Oxford St, entertainment in Leicester Square and restaurants in Covent Garden, Bloomsbury boasts a location that is hard to rival. Popular with city professionals, academics and international visitors, much of the accommodation tends to be beautifully presented studios, 1 and 2 bedroom flats. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2013 Nearest Stations Russell -

Bloomsbury Sub Area 10

E N A 1 L 2 N E 9 E m 3 1 R . o 9 t 1 G 3 1 3 5 G T R N I U O L 2 C 3 R E W E O R O 4 N T B R A 1 E 1 6 6 P t o 2 PH A 4 1 7 A h R g u o r 1 8 T 58 54 1 1 PH 9 1 0 56 9 1 1 t 1 r 2 5 1 0 1 u 3 t t o o o 1 1 1 7 C 0 0 ths 6 ffi ri 2 G 2 e 1 rin he at Cycle Hire 1 6 4 o 6 t Station Listed Building 62 1 8 5 1 1 Positive Building 9 T o 74 R t D E 67 A C 16.1m RO E R N 1 4 O Sub Area 10 3 t T D o 1 G 4 Car Park 5 S N 8 3 I t o e 15.2m 8 5 K R n L R A a Y A F L A 9 W l s ' nne b D u T R b 1 R 5 a C 1 8 TON P LA A 9 AT 1 H D 5 3 2 Y Bloomsbury Sub Area 10 3 6 1 El Sub Sta 1 1 TCBs 7 t 9 E o 3 0 1 PH 2 1 5 N 1 2 5 I 7 V L HILL 1 HE RBA 5 1 1 0 t 7 r C 7 RAWFORD PASSAGE 1 3 u 1 o t 5 7 f Balle 1 2 0 o C ol 3 3 5 o ho t 4 6 8 tral Sc 8 r Cen 8 1 o o 1 t 1 8 t 5 2 7 9 c t r 5 5 1 e r 1 6 u 1 L o t o t o o t 1 o 6 t 4 e 6 5 s p o 9 u C i H l e p 2 a r T 1 h T 5 C y c lwa PH 3 1 E ai S E R 2 d 1 1 E n 6 u 3 E 0 ro 9 r g 1 6 nde R 2 t o R U o 1 T t 7 1 1 47a T S 8 4 9 1 6 2 7 o S t 1 4 PH 7b M 8 1 8 1 A 2 5 1 S 3 5 o H t House S t 3 o Printing & P h 3 9 Caslon O 5 1 1 c 0 s 1 r O 9 9 ' D t 4 7 4 r o u R 3 T London College of 9 The London Institute e o h t t A 6 1 57 Distributive Trades e 3 C C 4 Design P O n 5 t 4 a T 3 i l R PCs S n College of Art & a 4 2 S t o 0 Post Central Saint Martins i a 2 B I t A 7 KE L 5 50 t a R' 49 o t S R 22 47 O t L 48 1 4 S W o Warner House 2 24 e 4 E 8 r 6 i 1 1 4 44 L 3 5 F 2 d B L 7 I 1 W 5 F H K N 5 3 C 4 y E 40 A o Drill Tower t 42 d 8 5 E B B 4 4 K 9 5 39 0 o R t B 1 6 1 5 A L R 8 36 g to 38 2 H 6 U f & 9 T e E -

Camden Outdoor

Camden IS OPEN FOR BUSINESS OUTDOOR SPACES Content: The Camden Events Service supports community, corporate and 01. Britannia Junction, Camden private events in the Borough. Town / Page 02 Camden have 70 parks and open spaces available for event hire. The 02. Russell Square / Page 06 events service offers a number of untraditional, experiential and street 03. Bloomsbury Square / Page 08 locations as well as many indoor venues. 04. Great Queen Street, Covent Camden is one of London’s creative hubs, Garden / Page 10 welcoming a number of events and activities throughout the year. These include street parties, filming, street promotions, experiential 05. Neal Street, Covent Garden / marketing, sampling and community festivals. Page 12 Our parks, open spaces and venues can accommodate corporate team building days, conferences, exhibitions, comedy nights, parties, weddings, exams, seminars and training. The events team are experienced in managing small and large scale events. 020 7974 5633 [email protected] 01 Camden is open for business Highgate Hampstead Town Frognal & Fitzjohns Fortune Green Gospel Oak Kentish Town West Hampstead Haverstock Belsize Cantelowes Swiss Cottage Camden Town 01 & Primrose Hill Kilburn St Pancras & Somers Town Regents Park King’s Cross 02 Bloombury Holborn & 03 Covent Garden The Camden Events Service supports community, 04 05 corporate and private events in the Borough. Camden have 70 parks and open spaces available for event hire. The events service offers a number of untraditional, experiential and street locations as well as many indoor venues. Camden is one of London’s creative hubs, welcoming a number of events and activities throughout the year. -

London 252 High Holborn

rosewood london 252 high holborn. london. wc1v 7en. united kingdom t +44 2o7 781 8888 rosewoodhotels.com/london london map concierge tips sir john soane’s museum 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields WC2A 3BP Walk: 4min One of London’s most historic museums, featuring a quirky range of antiques and works of art, all collected by the renowned architect Sir John Soane. the old curiosity shop 13-14 Portsmouth Street WC2A 2ES Walk: 2min London’s oldest shop, built in the sixteenth century, inspired Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop. lamb’s conduit street WC1N 3NG Walk: 7min Avoid the crowds and head out to Lamb’s Conduit Street - a quaint thoroughfare that's fast becoming renowned for its array of eclectic boutiques. hatton garden EC1N Walk: 9min London’s most famous quarter for jewellery and the diamond trade since Medieval times - nearly 300 of the businesses in Hatton Garden are in the jewellery industry and over 55 shops represent the largest cluster of jewellery retailers in the UK. dairy art centre 7a Wakefield Street WC1N 1PG Walk: 12min A private initiative founded by art collectors Frank Cohen and Nicolai Frahm, the centre’s focus is drawing together exhibitions based on the collections of the founders as well as inviting guest curators to create unique pop-up shows. Redhill St 1 Brick Lane 16 National Gallery Augustus St Goswell Rd Walk: 45min Drive: 11min Tube: 20min Walk: 20min Drive: 6min Tube: 11min Harringtonn St New N Rd Pentonville Rd Wharf Rd Crondall St Provost St Cre Murray Grove mer St Stanhope St Amwell St 2 Buckingham -

ORIENTATION HANDBOOK New Student Orientation & Enrolment Programme September 2008

School of Oriental and African Studies ORIENTATION HANDBOOK New Student Orientation & Enrolment Programme September 2008 Important !!! you in September Please bring this document with DIRECTOR’S WELCOME WELCOME I am very pleased to welcome all new students to SOAS. It is a very special place indeed, concerned with the places that matter in the 21st century (Africa, Asia and the Middle East) and the issues that matter (such as human rights, poverty reduction and globalisation, to name just three). It is full of passionate people who care about the world, who want to understand it and through understanding to change it. I’ve been at SOAS for two years now and have never regretted making the move. It is amazingly diverse, a very friendly place and incredibly stimulating. I am certain that you will enjoy your time here. It won’t always be easy – your preconceptions will be challenged and our programmes make serious demands on students – but it should be inspirational and enjoyable. One of our undergraduates wrote this year that “SOAS is such an addictive place – I may return in a few years either for my Masters or just a language course”. She’s right. So as well as welcoming you now, I look forward to welcoming you back to SOAS in the future! Professor Paul Webley Director and Principal CONTENTS INTRODUCTION What happens in Orientation Week? 2 Contact details/Buddy scheme 3 Finding your way around SOAS 4 Map 5 ORIENTATION International Students’ Welcome Day 6 Orientation Week for all students 8 Research Students’ Orientation 12 Orientation -

The Hatton 51-53 Hatton Garden London EC1N 8HN

Location map and directions to The Hatton This seven-storey training and meeting venue in London's Hatton Garden, provides an exceptionally stylish and vibrant training and conference environment. The Hatton 51- 53 Hatton Garden London , EC1N 8HN T: 020 7242 4123 F: 020 7242 1818 etc.venues - The Hatton 51-53 Hatton Garden London EC1N 8HN Nearest Underground Stations Farringdon Station (Metropolitan, Circle, Hammersmith & City Lines): Turn right out of the station. Walk up to the traffic lights, cross Farringdon Road. Continue walking up Greville Street. Take the third road on the right into Hatton Garden. The Hatton is on the right hand side (5 mins). Chancery Lane Station (Central Line): Take Gray’s Inn Rd exit 2. Walk down High Holborn to Holborn Circus. Turn left into Hatton Garden. Continue walking towards the top end of Hatton Garden. The Hatton is on the right (10 mins). Main Line Stations Farringdon Thameslink : Follow instructions as under Farringdon station. Kings Cross: Take Metropolitan, Circle or Hammersmith & City underground lines to Farringdon station. Follow instructions as under Farringdon station . Euston: Take Northern Line to Kings Cross. Change for Metropolitan, Circle or Hammersmith & City Lines to Farringdon. See instructions under Farringdon station. Liverpool Street : Take Central Line to Chancery Lane (see instructions under Chancery Lane) or take Metropolitan, Circle or Hammersmith & City Underground Lines to Farringdon (see instructions under Farringdon station). London Bridge: Take Thameslink to Farringdon. Follow instructions as under Farringdon station. Victoria: Take Victoria Line. Change at Oxford Circus for Central Line to Chancery Lane. Follow instructions as under Chancery Lane. -

Schedule of Open Spaces

Camden UDP Deposit Draft 2003 – Appendices Appendix 5 - Schedule of open spaces Key to Designations MOL Metropolitan Open Land PGSHI Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest LS London Squares AAllotments SSSI Sites of Special Scientific Interest LNR Local Nature Reserve SNCI (M) Site of Nature Conservation Importance (Metropolitan) SNCI (BI or BII) Site of Nature Conservation Importance (Borough I or Borough II) SNCI (L) Site of Nature Conservation Importance (Local) AW Ancient Woodland Public Open Spaces (Sites 1 to 115) Site Name Designation No. 1Agar Grove Estate 2Agar Grove Open Space 3Ainsworth Park 4Ampthill Square LS 5Antrim Grove Public Gardens 6Argyle School Community Garden 7Argyle Square LS 8Bell Moor 9Belsize Wood Open Space SNCI (BII) 11 Bloomsbury Square Gardens PGSHI, LS 12 Branch Hill Site 1 SNCI (BI) 13 Branch Hill Site 3 A, SNCI (BI) 14 British Museum Grounds 15 Broadhurst Copse 16 Brookes Market Open Space 17 Brunswick Square Gardens PGSHI, LS 18 Burlington Court Triangle 19 Calthorpe Project SNCI (L) 20 Camden Gardens LS 21 Camden Square Gardens LS 22 Camden Square Walkway 23 Canal Land (Baynes St. to St. Pancras Way) 24 Cantelowes Gardens 25 Chalcot Square 26 Chalton Street Open Space 27 Clarence Gardens 28 Clarence Way Open Space 163 Camden UDP Deposit Draft 2003 – Appendices Site Name Designation No. 29 College Crescent 30 College Gardens LS 31 Crabtree Fields 32 Crown Close Open Space 33 Cumberland Market 34 Elm Village 35 Elsworthy Road Enclosure LS 36 Eton Avenue LS 37 Euston Square Gardens LS 38 Falkland -

How to Find Us

How to find us New College of the Humanities is located in a five-storey Grade I listed Georgian townhouse built between 1776 and 1781. Situated opposite tranquil Bedford Square Garden, the College provides a quiet and relaxed environment in the heart of central London’s historic Bloomsbury area. Our address is Walk from Russell 19 Bedford Square Square Station London We are within six minutes’ walk WC1B 3HH of Russell Square tube station. Take the Bernard Street exit Directions from the station and turn left towards Russell Square. Cross Walk Woburn Place and continue We are within five minutes’ straight ahead with Russell walk of Tottenham Court Road, Square Garden on your left. Goodge Street, Euston Square Walk around the perimeter of and Russell Square tube WOBURN PLACE the gardens and then turn right Energybase Health & Fitness Centre BERNARD ST stations. NCH is a 20-minute into Montague Place. Continue University of BYNG PL London Student Russell Square walk from Euston Station or straight ahead, crossing Malet Central Tube MALET ST University King’s Cross/St Pancras. Street and then Gower Street. Senate House Russell Square SOUTHAMPTONCollege ROW TORRINGTON PL Library London Walk From Tottenham Continue another 100m and the Registry is on your right at Court Road Station 19 Bedford Square, opposite Goodge St MONTAGUE PLACE We are within five minutes’ Tube the gates to Bedford Square NCH GOWER ST walk of Tottenham Court Road Garden. (The Registry) TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD Bedford Bloomsbury tube station. Square The British Square BAYLEY ST MORWELL ST Museum Take the exit for the Dominion By train The nearest mainline train BEDFORD AV Theatre.