Bloomsbury and the Bloomsbury Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SACO Holborn - 5K Running Route SACO Holborn - 5K Running Route

SACO Holborn - 5k running route SACO Holborn - 5k running route finish start finish start Start @ 1k near - 2k Start @ 1k near - 2k SACO King’s Cross LCC Fire SACO King’s Cross LCC Fire Holborn St Pancras Brigade Holborn St Pancras Brigade 3k 4k 5k 3k 4k 5k St James’ Russell Sq Corman’s St James’ Russell Sq Corman’s Gardens Gardens Fields Gardens Gardens Fields Route Directions - Route Directions - at SACO onto Lamb’s Conduit Street onto Endsleigh Gardens at SACO onto Lamb’s Conduit Street onto Endsleigh Gardens onto Guilford Street onto Tavistock Square & Woburn onto Guilford Street onto Tavistock Square and Woburn at Gray’s Inn Road Place at Gray’s Inn Road Place onto Euston Road go round Russell Square Gardens onto Euston Road go round Russell Square Gardens onto Melton Road onto Guilford Street onto Melton Road onto Guilford Street go round St James’ Gardens and onto Guilford Place go round St James’ Gardens and onto Guilford Place return onto Euston Road. Lamb’s Conduit Street - stop at return onto Euston Road. Lamb’s Conduit Street - stop at cross Euston Road and go along SACO cross Euston Road and go along SACO Gorden Street Gorden Street we give you more we give you more SACO Holborn - 10k running route SACO Holborn - 10k running route finish finish start start Start @ 2k 4k Start @ 2k 4k SACO All Souls Regent’s Park SACO All Souls Regent’s Park Holborn Church Boating Lake Holborn Church Boating Lake 6k 8k 10k 6k 8k 10k Regent’s Euston Sq Lamb’s Regent’s Euston Sq Lamb’s Park Station Conduit St Park Station Conduit St Route Directions -

Roman House Is a Rare Opportunity to Acquire a Luxury Apartment Or Penthouse in a Premier City of London Location

1 THE CITY’S PREMIER NEW ADDRESS 2 3 ROMAN HOUSE IS A RARE OPPORTUNITY TO ACQUIRE A LUXURY APARTMENT OR PENTHOUSE IN A PREMIER CITY OF LONDON LOCATION. THE SQUARE MILE’S RENOWNED RESTAURANTS, LUXURY SHOPS AND WORLD CLASS CULTURAL VENUES ARE ALL WITHIN WALKING DISTANCE; WHILE CHIC, SUPERBLY WELL PLANNED INTERIORS CREATE A BOUTIQUE HOTEL STYLE LIVING ENVIRONMENT. AT ROMAN HOUSE, BERKELEY OFFERS EVERYTHING THAT COSMOPOLITAN TASTES AND INTERNATIONAL LIFESTYLES DEMAND. 4 1 THE EPITOME THE CITY OF OF BOUTIQUE WESTMINSTER CITY LIVING THE CITY Contents 5 Welcome to a new style of City living 28 On the world stage 6 Welcome home 30 On the city borders 8 An unparalleled living experience 32 Be centrally located 11 Y 35 A world class business destination 12 Your personal oasis 37 Wealth and prestige 14 A healthy lifestyle right on your doorstep 38 London, the leading city 16 Café culture 41 London, the city for arts and culture 18 Find time for tranquillity 42 A world class education 20 Y 44 Zone 1 connections 23 Vibrant bars 46 Sustainable living in the heart of the city 25 Shop in Royal style 47 Designed for life 26 London, the global high street 48 Map 2 3 Computer Generated Image of Roman House is indicative only. Y Welcome to years, and is considered a classic of its time. Now, it is entering a prestigious new era, expertly refurbished by Berkeley to provide ninety exquisite new homes in the heart of the City, a new style with a concierge and gymnasium for residents’ exclusive use. -

Bloomsbury Scientists Ii Iii

i Bloomsbury Scientists ii iii Bloomsbury Scientists Science and Art in the Wake of Darwin Michael Boulter iv First published in 2017 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ ucl- press Text © Michael Boulter, 2017 Images courtesy of Michael Boulter, 2017 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Michael Boulter, Bloomsbury Scientists. London, UCL Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350045 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 006- 9 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 005- 2 (pbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 004- 5 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 007- 6 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 008- 3 (mobi) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 009- 0 (html) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787350045 v In memory of W. G. Chaloner FRS, 1928– 2016, lecturer in palaeobotany at UCL, 1956– 72 vi vii Acknowledgements My old writing style was strongly controlled by the measured precision of my scientific discipline, evolutionary biology. It was a habit that I tried to break while working on this project, with its speculations and opinions, let alone dubious data. But my old practices of scientific rigour intentionally stopped personalities and feeling showing through. -

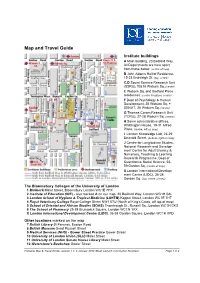

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

Design and Access Statement

New Student Centre Design and Access Statement June 2015 UCL - New Student Centre Design and Access Statement June 2015 Contributors: Client Team UCL Estates Architect Nicholas Hare Architects Project Manager Mace Energy and Sustainability Expedition Services Engineer BDP Structural and Civil Engineer Curtins Landscape Architect Colour UDL Cost Manager Aecom CDM Coordinator Faithful & Gould Planning Consultant Deloitte Lighting BDP Acoustics BDP Fire Engineering Arup Note: this report has been formatted as a double-sided A3 document. CONTENTS DESIGN ACCESS 1. INTRODUCTION 10. THE ACCESS STATEMENT Project background and objectives Access requirements for the users Statement of intent 2. SITE CONTEXT - THE BLOOMSBURY MASTERPLAN Sources of guidance The UCL masterplan Access consultations Planning context 11. SITE ACCESS 3. RESPONSE TO CONSULTATIONS Pedestrian access Access for cyclists 4. THE BRIEF Access for cars and emergency vehicles The aspirational brief Servicing access Building function Access 12. USING THE BUILDING Building entrances 5. SITE CONTEXT Reception/lobby areas Conservation area context Horizontal movement The site Vertical movement Means of escape 6. INITIAL RESPONSE TO THE SITE Building accommodation Internal doors 7. PROPOSALS Fixtures and fittings Use and amount Information and signage Routes and levels External connections Scale and form Roofscape Materials Internal arrangement External areas 8. INTERFACE WITH EXISTING BUILDINGS 9. SUSTAINABILITY UCL New Student Centre - Design and Access Statement June 2015 1 Aerial view from the north with the site highlighted in red DESIGN 1. INTRODUCTION PROJECT BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES The purpose of a Design and Access Statement is to set out the “The vision is to make UCL the most exciting university in the world at thinking that has resulted in the design submitted in the planning which to study and work. -

Huntley Street London WC1E 6AU United Kingdom Entrance: Huntley Street

Lab Address: UCL EGA Institute for Women's Health Huntley Street London WC1E 6AU United Kingdom Entrance: Huntley Street How to find us By Tube: We are easy to reach from a number of tube stations. From Euston Square (Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith and City lines) When exiting the station follow signs for UCL (University College London). You should then exit on the corner of Gower Place and Gower Street. Head south down Gower Street and take the second street on your right (University Street). Head down University Street and take the first left (Huntley Street). The first door you come to on the left is the Medical school building (door is up a couple of steps in an alcove). The door has a card entry so please wait under the shelter and one of the research team will meet you in the alcove. From Warren Street (Victoria and Northern lines) Exit the station, turning right on to Tottenham Court road, crossing the small street in front of you (Warren Street) and walk south down Tottenham Court road. Cross over the road (to the side with Sainsbury’s and PC World) and continue along Tottenham Court Road until you reach the second road on the left (University Street). Turn down University Street and take the first road on the right (Huntley Street). The first door you come to on the left hand side of the road is the Medical school building (door is up a couple of steps in an alcove). The door has a card entry so please wait under the shelter and one of the research team will meet you in the alcove. -

Neighbourhood Area Application

Area Application This is an application for definition of the boundary of the “Drummond Street Neighbourhood Forum Area”. The organisation making this application is the proposed “Drummond Street Neighbourhood Forum” which is a relevant body for the purposes of section 61G of the 1990 Act. The “Drummond Street Neighbourhood Forum” is capable of being a qualifying body for the purposes of the Localism Act 2011 and is proposing this area application alongside an application for it to be so recognised. 1 CONTENTS 1 CONTENTS 1 2 BOUNDARY DEFINITION 1 3 AREA DESCRIPTION 1 4 BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION 3 5 BOUNDARY JUSTIFICATION 3 6 BOUNDARY MAP 5 2 BOUNDARY DEFINITION The exact boundary of the area is defined by the high resolution map file included with our application. A low resolution copy of the map is shown in section 6 ‘Boundary Map’. 3 AREA DESCRIPTION The area is triangle around the junction of North Gower and Drummond Street and bounded entirely by existing larger roads – to the south by Euston Road, to the west by Hampstead Road, and to the east by Melton Street and Cardington Street. Drummond Street itself is well known for its curry houses and specialist shops. It is an area of mixed use: ● Residential – St George's Mews and Starcross Street are almost entirely residential with a mix of owner occupied houses and apartments, private rented, social housing and sheltered accommodation. Starcross Street has a public house, the Exmouth Arms at the eastern end. Cobourg Street, North Gower Street are also primarily residential with some offices and retail, including Bengal Canteen, Piccolo Cafe and Speedy's Cafe, known for the filming of the Sherlock Holmes television series. -

This Document Has Been Superseded by the Euston Station OSD – Memorandum of Information

– OSD been PQQ EUSTONhas STATIONStation DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY CANARY WHARF Euston Information document KING’S CROSS the of by CITY OF LONDON This ST PANCRAS INTERNATIONAL supersededMemorandum EUSTON STATION SOUTH BANK WEST END REGENT’S PARK working together to redevelop Euston – OSD been PQQ has Station Euston The DepartmentInformation for Transport and Network Rail intend to appoint documentthe of a long-term strategic Master Development Partner for the byredevelopment and regeneration of land at Euston Station This one of the largest development opportunities in central London supersededMemorandum – For illustrative purposes only Working together with the local community and– the Master Development Partner, we want to create a Euston that provides a great experience for the community, travellers, businesses and DEVELOPING visitors. Our aim is to generate economic development (including new jobs and homes) above and OSDaround the station and throughout the wider area, as well as to connect people and places across national and high-speed rail networks, London Underground and surface transport. THE VISION been PQQ has Station Euston For illustrative purposes only Inspirational place - Embraces local heritage A centre for thriving localInformation Continues the success and Network of green spaces Gateway to the UK and Europe documentthe communities of growth of the area by This Mixed use district which is a Generates long-term value Stimulates creativity and Promotes accessibility Robust urban framework magnet for business innovation supersededMemorandum – LOCATION OSD CAMDEN Euston Station is situated in the London Borough of Camden, in an area characterised by a diverse mix of uses, including some of London’s most ANGEL prestigious residentialbeen accommodation neighbouring Regent’s Park, premier commercial and office premises, and PQQworld-class educational, research, and HOLBORN cultural institutions. -

University College Hospital

The Neonatal Transfer Service Neonatal Transport Service The ambulance that comes to collect your for London baby will be specially designed and equipped with the necessary specialist equipment to provide intensive care for sick newborn ba- Parent Information Leaflet bies. Your baby will be placed in an incubator to keep it warm, will have its heart rate, breath- ing and blood pressure monitored and may require equipment to help with breathing. University College This will ensure a safe transfer to the unit Hospital that will care for your baby. Neonatal Unit The transport team will all be specialists in the care of sick, newborn babies and will in- 235 Euston Road clude a doctor or an advanced neonatal nurse practitioner, a senior neonatal nurse London and a Paramedic. They will all have under- NW1 2BU taken specialist transport training. To contact our service: (Map on the back page) 0203 594 0888 [email protected] www.neonatal.org.uk Tel: Switchboard: 0845 155 5000 (Ext 8696 / 8693) www.uclh.org Information on about the Neonatal Unit and local Amenities Cash points One on site Catering/refreshments By bus: There is a parents Kitchen Tottenham Court Road: North bound (Warren Street station) Bus No's 10, 73, 24, 29, 134 Local catering outlets/shops Plenty on surrounding streets Gower Street: South bound (University Street) Bus No's 10, 24, 29, 73, 134 Access to Religious Support Euston Road à Bus No's 18, 27, 30, 88 All Faiths By tube Access to interpreters Warren Street (Northern / Victoria Lines) 2 days notice is required for booking an interpreter. -

Street 2009 2009

Site # Site Address TLRN/Borough Programmed Sites (FY) 00/000012 CHEAPSIDE - KING STREET - QUEEN STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 00/000013 QUEEN VICTORIA STREET - QUEEN STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 QUEEN VICTORIA STREET - CANNON STREET - MANSION 00/000016 HOUSE TUBE Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000035 BUCKINGHAM GATE - QUEENS GARDENS - BIRDCAGE WALK Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000077 SOUTH AUDLEY STREET - MOUNT STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000085 PARK STREET - UPPER BROOK STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 A4 STRAND - B401 WELLINGTON STREET - A301 LANCASTER 01/000089 Borough PLACE 2009 - 2010 01/000090 CHARING CROSS ROAD - CRANBOURN STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000092 PARK STREET - GREEN STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000094 VICTORIA EMBANKMENT - TEMPLE PLACE TLRN 2009 - 2010 01/000124 BAYSWATER ROAD - LEINSTER TERRACE Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000133 WESTBOURNE TERRACE - CRAVEN ROAD Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000174 BAKER STREET - PORTMAN SQUARE - FITZHARDINGE Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000175 SEYMOUR STREET - PORTMAN SQUARE - PORTMAN STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000177 WIGMORE STREET - DUKE STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000179 WIGMORE STREET - MARYLEBONE LANE Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000180 WIGMORE STREET - WELBECK STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000181 WIGMORE STREET - WIMPOLE STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000193 BAKER STREET - BLANDFORD STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 01/000205 OXFORD STREET - PARK STREET - PORTMAN STREET Borough 2009 - 2010 OXFORD STREET - ORCHARD STREET - NORTH AUDLEY 01/000206 Borough STREET 2009 - 2010 01/000207 OXFORD STREET - DUKE STREET Borough 2009 - -

London 252 High Holborn

rosewood london 252 high holborn. london. wc1v 7en. united kingdom t +44 2o7 781 8888 rosewoodhotels.com/london london map concierge tips sir john soane’s museum 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields WC2A 3BP Walk: 4min One of London’s most historic museums, featuring a quirky range of antiques and works of art, all collected by the renowned architect Sir John Soane. the old curiosity shop 13-14 Portsmouth Street WC2A 2ES Walk: 2min London’s oldest shop, built in the sixteenth century, inspired Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop. lamb’s conduit street WC1N 3NG Walk: 7min Avoid the crowds and head out to Lamb’s Conduit Street - a quaint thoroughfare that's fast becoming renowned for its array of eclectic boutiques. hatton garden EC1N Walk: 9min London’s most famous quarter for jewellery and the diamond trade since Medieval times - nearly 300 of the businesses in Hatton Garden are in the jewellery industry and over 55 shops represent the largest cluster of jewellery retailers in the UK. dairy art centre 7a Wakefield Street WC1N 1PG Walk: 12min A private initiative founded by art collectors Frank Cohen and Nicolai Frahm, the centre’s focus is drawing together exhibitions based on the collections of the founders as well as inviting guest curators to create unique pop-up shows. Redhill St 1 Brick Lane 16 National Gallery Augustus St Goswell Rd Walk: 45min Drive: 11min Tube: 20min Walk: 20min Drive: 6min Tube: 11min Harringtonn St New N Rd Pentonville Rd Wharf Rd Crondall St Provost St Cre Murray Grove mer St Stanhope St Amwell St 2 Buckingham -

Document.Pdf

Alba Hampstead ny Stre Pentonville Road KINGS CROSS e Regent’s Park t King’s Cross St Pancras R oa d Gray’s Inn Pa London Euston rk Road Road e k Plac oc ad ist v Euston Square Ta Euston Ro LISSON GROVE Warren Street SAINT PANCRAS Great Portland Street bone Road Baker Street Maryle Regent’s Park Great Po London Marylebone Southa FITZROVIA Russell To Square m rt ttenha pton land Street Goodge Street R Edgware Road m o w Cour MARYLEBONE t Ro olborn igh H ad H reet PADDINGTON Oxford St Tottenham Court Road et Oxford Stre Oxford Circus Bond Street Marble Arch COVENT GARDEN MAYFAIR Hyde Park thern Nor Victoria Hammersmith & City Piccadilly Circle Metropolitan Eurostar HS1 Javelin Thameslink Thameslink National Rail ancras Piccadilly St P King’s Cross HS2 (from 2026) Victoria Northern Northern Euston Circle olitan erground Ov National Rail Metrop Hammersmith & City Camden Town BARNSBURY ESTAT E Mornington Crescent 1 2 ISLINGTON 3 4 Angel 6 1. Regent High School Ha 5 2. Google 3. Universal Music Operations Ltd m 7 4. Bio Nano Consulting pstead onville Road 8 Pent 5. Warwick in London 6. Edith Neville Primary School 9 7. Somers Town Community Association King’s Cross St Pancras Regent’s Park 10 8. The Francis Crick Institute R 9. New Horizon Youth Centre oa 11 10. The Alan Turing Institute d 12 11. British Library 12.SQW 13. Digital Catapult KINGS CROSS 14. Arts Catalyst Pa 13 15. The Place London Euston 14 16. Society of College, National and rk Road Gray’s In University Libraries 15 17.