And Gender-Specific Burden and Complexity of Multimorbidity in Taiwan, 2003–2013: a Cross-Sectional Study Based on Nationwide Claims Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-005>

| FRIDAY, JUNE 5, 2020 | THE STRAITS TIMES | happenings life C5 Boon Chan Assistant Life Editor recommends Picks POP SOUNDS OF MY LIFE William Wei Music Cat owners will be able to identify with the cute track Cat Republic, which has lyrics like “Poop and pee for you, snacks and toys for you/I’m ignoring you now, unless you open up a can” and “You will serve me forever/You will love me forever”. Other slice-of-life songs abound on Taiwanese singer-songwriter William Wei’s mostly Mandarin fifth album. POP From the chirpy English track See You On Monday and HUG IN OUR HEARTS the breezy I Wrote A Song For You (about the pleasure and Billkin featuring Jaylerr meaning of music) to the more contemplative At Thirty (“I chase after time, only to realise/Time is chasing me”) Thai actor-singer Billkin’s new Thai and Best Meal In The World (“If I could eat away my single, Hug In Our Hearts, starts off as sadness, digest what I miss”), there is plenty here to relate a forlorn ballad as he sings quietly to and be engaged by. about missing someone (“Open the The musician, who also goes by WeiBird, has dedicated door for loneliness/Since we haven’t the album to his late grandmother and in the track seen each other”). labelled Credits, one can hear her and his family sweetly It builds to a catchy chorus before cheering him on. fellow actor-singer Jaylerr jumps in The album can be a little sprawling and unwieldy at with a sunny rap, which brightens the times, but then again, so is life. -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

Literary Tricksters in African American and Chinese American Fiction

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2000 Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction Crystal Suzette anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the Ethnic Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Crystal Suzette, "Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction" (2000). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623988. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-z7mp-ce69 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric LuMing Mao Morris Young Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Mao, LuMing and Young, Morris, "Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric" (2008). All USU Press Publications. 164. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/164 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS REPRESENTATIONS Doing Asian American Rhetoric edited by LUMING MAO AND MORRIS YOUNG UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2008 Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Cover design by Barbara Yale-Read Cover art, “All American Girl I” by Susan Sponsler. Used by permission. ISBN: 978-0-87421-724-7 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Representations : doing Asian American rhetoric / edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-87421-724-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) 1. English language--Rhetoric--Study and teaching--Foreign speakers. 2. Asian Americans--Education--Language arts. 3. Asian Americans--Cultural assimilation. -

Salon Brochure

Charlotte White’s 2019/20 MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION Celebrating Our 31st Season OPENING GALA AWARDS CONCERT Wednesday, September 25, 2019 | 7 PM Kosciuszko Foundation 15 East 65th Street, New York, NY Dear Friends, Welcome to the 31st Season of the Salon de Virtuosi! We are delighted to continue the legacy of our founder Charlotte White by offering a series of unforgettable concerts featuring the most talented young musicians from around the world in intimate 19th Century salon settings throughout New York City, where you will have the opportunity to hear and get to know exceptional young artists who are destined to become our future “greats.” We celebrate the start of the season with our acclaimed Gala Awards Concert on September 25, 2019 at the elegant Kosciuszko Foundation, where we will present five of our2019 Career Grant Winners in a special concert hosted by the renowned musicologist and longtime Salon de Virtuosi friend Robert Sherman of WQXR. Other highlights of the Fall season include our Autumn in New York Concert on November 6, 2019 at the Liederkranz Foundation, presenting a talented young American pianist/ composer and a rising young American violinist, with a special guest appearance by 2017 Salon Career Grant Winner Asi Matathias. Our Holiday Concert on December 12, 2019 at the beautiful home of Elizabeth and Lewis Bryden at Hotel des Artistes will feature a phenomenal 16-year old violinist and an exciting American clarinetist. In the Spring we will continue our unique collaboration with the Consulates of Hungary and India and will also present a concert at the Consulate General of France, each featuring remarkable young talents. -

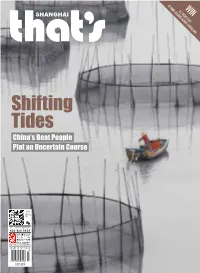

Shifting Tides China’S Boat People Plot an Uncertain Course

AT FOUR SEA WIN A 2- N SON IGHT STAY S R E SORT CHIANG MAI Shifting Tides China’s Boat People Plot an Uncertain Course 城市漫步上海 英文版 7 月份 国内统一刊号: CN 11-5233/GO China Intercontinental Press JULY 2018 that’s Shanghai 《城市漫步》上海版 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 中国北京 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 邮编 100045 Published by China Intercontinental Press Address: 11th Floor South Building, HengHua linternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing 100045, PRC http://www.cicc.org.cn 社长 President of China Intercontinental Press: 陈陆军 Chen Lujun 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 付平 Fu Ping 主编 Executive Editor: 袁保安 Yuan Baoan 编辑 Editor: 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 Circulation: 李若琳 Li Ruolin Chief Editor Dominic Ngai Section Editors Erica Martin, Cristina Ng Production Manager Ivy Zhang Designer Joan Dai, Nuo Shen Contributors Mia Li, Logan Brouse, Noelle Mateer, Matthew Bossons, Dominique Wong, Iris Wang, Valerie Osipov, Tess Humphrys, Yuzhou Hu, Aimee Burlamacchi, Yannick Faillard, Chloe Dumont, Samantha Kennedy, Molly Jett, Daniel Plafker, Tristin Zhang Copy Editor Amy Fabris-Shi HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 021-8023 2199 传真 : 021-8023 2190 Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市越秀区麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Room 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Yuexiu District, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 -

Crosscurrents Scurrents

CROSSCURRENTS 2004/2005 1 Center Celebrates 35th Anniversary! Vols. 26, No. 2 and 27, No. 1 (Academic Year 2003/2004) CCrroosssCurrentssCurrents Newsmagazine of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center Asian American Studies IDP Becomes a Department UCLA welcomes a new department this Fall 2004: the Department of Asian American Studies. Since 1969 UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, which is celebrating its 35th anniversary this year, has played a he initial goal of leadership role in developing the field of Asian Ameri- the Center was to can Studies in U.S. academia and has helped form the T Asian American Studies Interdepartmental Degree Pro- gram (IDP), which has now transformed into the De- “enrich the experience partment of Asian American Studies. The official es- tablishment of the new department is the result of of the entire university the dedication, perseverance, and hard work of the fac- ulty, staff, students, alumni, and community support- by contributing to an ers over the course of more than 10 years. The IDP’s departmentalization proposal was reviewed by major understanding of the committees of the Academic Senate and received over- whelming support and enthusiastic endorsement. The long neglected history, Executive Board of the Academic Senate voted in fa- vor of departmentalization, and the Chancellor enthu- rich cultural heritage, siastically approved this truly historical move from IDP to Department in August 2004. There is now both a and present position of Center and Department of Asian American Studies at UCLA, working in a dynamic fashion. Asian Americans in our Developing an Asian American Studies curriculum society.” at UCLA was an important part of the mission for the Asian American Studies Center, which was —from the Center’s founding founded in 1969 as an organized research unit (ORU). -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) X004 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service " The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. A For the 2004 calendar year, or tax year beginning ' ' 7'iL ! , 2004, and endmq / G~-rt~ 3 / , 20 Of' D Employer identification number B Check if applicable please C Name of organization °6° iRS The 98 ;6001255 Address change label or University of British Columbia or Number and street (or P .O . box if mail is not delivered to street adds Room/suite I E Telephone number Name change pint 2075 Wesbrook Mall E Initial return sere ( 604 ) 822-5770 Specific 0 Final return Inswc- City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 F Accounting method U Cash VJ Accrual Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z1 D Amended return D Other (specify) H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations D Application pending 9 Section 501(c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(i) nonexempt charitable trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Forth 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? LJ Yes 0 No G Website: " WVWV.ubC.Ca H(b) If "Yes," enter number of affiliates 1~ . .. .. .. H(c) Are all affiliates included? ,i/19 E]Yes El No J Organization type (check only one) " 0 501(c) ( ) ~4 (insert no .) El 4947(a)(1) or El 527 (If "No," attach a list . -

Curiosity Keeps Searching for Signs of Life on Mars - Taipei Times 11/7/12 8:13 AM

Curiosity keeps searching for signs of life on Mars - Taipei Times 11/7/12 8:13 AM 自由電子報 | 影音娛樂 | 旅遊玩樂 | 好康報報 | 自由部落 Home Front Page Taiwan News Business Editorials Sports World News Features Bilingual Pages Search Home / World News Sun, Nov 04, 2012 - Page 7 News List Print Mail Facebook Twitter plurk funp Curiosity keeps searching for signs of life on Mars ReutersS, CAPE CANAVERAL, Florida Initial analysis of the atmosphere of Mars from NASA’s rover Curiosity has shown no sign of Most Popular methane, a gas detected Listing from 2012-11-01 to 2012-11-08 previously by remote sensors, Most read Most e-mailed researchers said on Friday. 1 Tech Review: Apple’s iOS 6 Maps On Earth, more than 90 percent 2 China hampers trade talks: EU official of the methane in the atmosphere 3 Taipei’s missile ‘umbrella’ to be bolstered: results from living organisms and military its presence in the Martian 4 Calendar aims to raise pro-localization atmosphere, first detected in consciousness 2003, raised the prospect of 5 Editorial: Time Ma dropped the numbers microbial life on the planet. game Although no methane was detected during Curiosity’s first detailed atmospheric analysis, MORE scientists working under the auspices of the US space agency plan to keep looking. “The search goes on,” Curiosity scientist Paul Mahaffy, from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, told reporters on Friday. In addition to chemically analyzing soil and rocks, Curiosity is equipped to sample and study gases in the planet’s thin atmosphere. The rover’s onboard laboratory looked for methane in concentrations as small as 5 parts per billion. -

Commencement-Program-2007.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA 251st Commencement ONDAY, MAY 14, 2007 The University of Pennsylvania KEEPING FRANKLIN'S PROMISE In the words of one elegiac tribute, "Great men have two lives: one which occurs while they work on this earth; a second which begins at the day of their death and continues as long as their ideas and conceptions remain powerful." These words befit the great Benjamin Franklin, whose inventions, innovations, ideas, writings, and public works continue to shape our thinking and renew the Republic he helped to create and the institutions he founded, including the University of Pennsylvania. Nowhere does Franklin feel more contemporary, more revolutionary, and more alive than at the University of Pennsylvania. His startling vision of a secular, nonsectarian Academy that would foster an "Inclination join'd with an Ability to serve Mankind, one's Country, Friends and Family" has never ceased to challenge Penn to redefine the scope and mission of the modern American university. When pursued vigorously and simultaneously, the two missions — developing the inclination to do good and the ability to do well — merge to help form a more perfect university that educates more capable citizens for our democracy. Penn has embodied and advanced Franklin's revolutionary vision for more than 267 years. Throughout its history, Penn has extended the frontiers of higher learning and research to produce graduates and scholars whose work has enriched the nation and all of humanity. The modern liberal arts curriculum as we know it can trace its roots to Franklin's innovation to have Penn students study international commerce and foreign languages. -

Rethinking the Asian American Movement

RETHINKING THE ASIAN AMERICAN MOVEMENT Although it is one of the least-known social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, the Asian American movement drew upon some of the most powerful currents of the era, and had a wide-ranging impact on the political landscape of Asian America, and more generally, the United States. Using the racial discourse of the Black Power and other movements, as well as anti-war activist and the global decolonization movements, the Asian American movement succeeded in creating a multiethnic alliance of Asians in the United States and gave them a voice in their own destinies. Rethinking the Asian American Movement provides a short, accessible overview of this important social and political movement, highlighting key events and key figures, the movement’s strengths and weaknesses, how it intersected with other social and political movements of the time, and its lasting effect on the country. It is perfect for anyone wanting to obtain an introduction to the Asian American movement of the twentieth century. Daryl Joji Maeda is Associate Professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder, USA. Downloaded by [Brown University] at 11:31 06 November 2017 American Social and Political Movements of the Twentieth Century Series Editor: Heather Ann Thompson Rethinking the American Anti-War Movement By Simon Hall Rethinking the Asian American Movement By Daryl Joji Maeda Downloaded by [Brown University] at 11:31 06 November 2017 RETHINKING THE ASIAN AMERICAN MOVEMENT Daryl Joji Maeda Downloaded by [Brown University] at 11:31 06 November 2017 First published 2012 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2012 Taylor & Francis The right of Daryl Joji Maeda to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

From Imperial Soldier to Communist General: the Early Career of Zhu De and His Influence on the Formation of the Chinese Red Army

FROM IMPERIAL SOLDIER TO COMMUNIST GENERAL: THE EARLY CAREER OF ZHU DE AND HIS INFLUENCE ON THE FORMATION OF THE CHINESE RED ARMY By Matthew William Russell B.A. June 1983, Northwestern University M.A. June 1991, University of California, Davis M.Phil. May 2006, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 17, 2009 Dissertation directed by Edward A. McCord Associate Professor of History and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Matthew W. Russell has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 25, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. FROM IMPERIAL SOLDIER TO COMMUNIST GENERAL: THE EARLY CAREER OF ZHU DE AND HIS INFLUENCE ON THE FORMATION OF THE CHINESE RED ARMY Matthew William Russell Dissertation Research Committee: Edward A. McCord, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Ronald H. Spector, Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member Daqing Yang, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2009 by Matthew W. Russell All rights reserved iii Dedication This work is dedicated to my mother Dorothy Diana Ing Russell and to my wife Julia Lynn Painton. iv Acknowledgements I was extremely fortunate to have Edward McCord as my adviser, teacher, and dissertation director, and I would not have been able to complete this program without his sound advice, guidance, and support.