Canada's Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13542 DIP MAG May/June.V4

Christina Spencer on 15 Years of Canadian Diplomacy November–December 2004 Mexican Evolution Ten Years of Free Trade Maria Teresa Garcia de Madero, Ambassador of Mexico Allan Thompson critiques the Foreign Policy Review process The trouble with Jeremy Rifkin Democracy for export: To impose or lead by example? And introducing Margaret Dickensen, gourmet goddess Nov/Dec 2004 CDN $5.95 PM 40957514 Volume 15, Number 6 PUBLISHER Our 15th anniversary issue Lezlee Cribb EDITOR Jennifer Campbell CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Table of Daniel Drolet CULTURE EDITOR Margo Roston CONTENTS COPY EDITOR Roger Bird EDITOR EMERITUS DIPLOMATICA| Bhupinder S. Liddar Happy birthday to us . .4 CONTRIBUTING WRITERS News and Culture . .5 George Abraham Roger Bird Envoy’s Photo Album . 8 Laura Bonikowsky Cleaning up the Carribean . .10 Thomas D’Aquino Diplo-dates . .11 Margaret Dickensen Recent Arrivals . .12 Joe Geurts Canadian Appointments . .14 Gurprit Kindra David Long Carlos Miranda DISPATCHES| Christina Spencer Diplomacy over this magazine’s lifespan Allan Thompson Christina Spencer looks back on 15 years . .15 Philémon Yang Dating diplomacy: A chronological countdown . 19 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY Jana Chytilova Democracy to go CONTRIBUTING ARTIST Differing diplomatic approaches to freedom . .20 Hilary Ashby The Canadian Parliamentary Centre advocates the subtle approach . .24 CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHER Sam Garcia After NAFTA OFFICE ASSISTANT Trade Winds: Mexico’s ambassador talks trade . .25 Colin Anderson NAFTA by the numbers . .27 OTTAWA ADVERTISING SALES Lezlee Cribb (613) 789-6890 DELIGHTS| NATIONAL ADVERTISING SALES Entertaining: Margaret Dickensen’s memories of the Soviet Union . .29 On the Go: Margo Roston on the sounds of a Russian symphony . .32 (613) 234-8468, ext. -

Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: an Agenda for Intervention

Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: An Agenda for Intervention Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: An Agenda for Intervention Michael W. Manulak Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Manulak, Michael W., 1983- Canada and the Kosovo crisis : an agenda for intervention / Michael W. Manulak. (Martello papers, ISSN 1183-3661 ; 36) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-55339-245-3 1. Kosovo War, 1998-1999—Participation, Canadian. 2. Canada— Military policy. I. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Centre for International Relations II. Title. III. Series: Martello papers ; 36 DR2087.6.F652C3 2010 949.7103 C2010-907064-X © Copyright 2011 Martello Paper Series Queen’s University’s Centre for International Relations (QCIR) is pleased to present the latest in its series of monographs, the Martello Papers. Taking their name from the distinctive towers built during the nineteenth century to defend Kingston, Ontario, these papers cover a wide range of topics and issues in foreign and defence policy, and in the study of international peace and security. How governments make decisions in times of crisis is a topic which has long fascinated both theorists and practitioners of international politics. Michael Manulak’s study of the Canadian government’s decision to take part in NATO’s use of force against Serbia in the spring of 1999 deploys a novel social-scientific method to dissect the process whereby that decision was made. In that respect this paper descends from a long line of inquiry going back to the 1960s and the complex flow-charts designed by “scientific” students of foreign policy. -

September 16, 2020 Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’S Republic of China Wang Yi

September 16, 2020 Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China Wang Yi Re: The Immediate Release of and Justice for Dr Wang Bingzhang Dear Minister Wang Yi, We write to bring to your attention the dire situation of Dr Wang Bingzhang, a Chinese national with a strong Canadian connection languishing in solitary confinement in Shaoguan Prison. In 1979, the Chinese Government sponsored Dr Wang’s studies at McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine. In 1982, Dr Wang became the first Chinese national to be awarded a PhD in North America. Newspapers in China and around the world praised his monumental accomplishments. Dr Wang then decided to forego his promising career in medicine to dedicate his life to human rights, firmly believing that self-sacrifice for his country was the most noble value. He identified as a Chinese patriot, and should have returned home a hero. Instead, in 2002, he was kidnapped in Vietnam and forcibly brought to China. It was only after five months of incommunicado detention that he was notified of the charges brought against him. Not once was he permitted to contact his family or a lawyer. At trial, Dr Wang was denied the opportunity to speak or present evidence, and no credible evidence or live witness testimony was presented against him. Moreover, the trial was closed to the public and lasted only half a day. The Shenzhen People’s Intermediate Court sentenced Dr Wang to life in solitary confinement. Dr Wang appealed the decision, but the sentence was upheld a month later, where he was again barred from speaking. -

Ministerial Staff: the Life and Times of Parliament’S Statutory Orphans

MINISTERIAL STAFF: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF PARLIAMENT’S STATUTORY ORPHANS Liane E. Benoit Acknowledgements Much of the primary research in support of this paper was gathered through interviews with more than twenty former and current public servants, lobbyists, and ex-exempt staff. I am sincerely grateful to each of them for their time, their candour and their willingness to share with me the benefit of their experience and insights on this important subject. I would also like to acknowledge the generous assistance of Cathi Corbett,Chief Librarian at the Canada School of Public Service,without whose expertise my searching and sleuthing would have proven far more challenging. 145 146 VOLUME 1: PARLIAMENT,MINISTERS AND DEPUTY MINISTERS And lastly, my sincere thanks to C.E.S Franks, Professor Emeritus of the Department of Political Studies at Queen’s University, for his guidance and support throughout the development of this paper and his faith that, indeed, I would someday complete it. 1 Where to Start 1.1 Introduction Of the many footfalls heard echoing through Ottawa’s corridors of power, those that often hit hardest but bear the least scrutiny belong to an elite group of young, ambitious and politically loyal operatives hired to support and advise the Ministers of the Crown. Collectively known as “exempt staff,”1 recent investigations by the Public Accounts Committee and the Commission of Inquiry into the Sponsorship Program and Advertising Activities,hereafter referred to as the “Sponsorship Inquiry”, suggest that this group of ministerial advisors can, and often do, exert a substantial degree of influence on the development,and in some cases, administration, of public policy in Canada. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2011 In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009 University of Calgary Press Donaghy, G., & Carroll, M. (Eds.). (2011). In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909-2009. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48549 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com IN THE NATIONAL INTEREST Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009 Greg Donaghy and Michael K. Carroll, Editors ISBN 978-1-55238-561-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

2004-05-12 Pre-Election Spending

Federal Announcements Since April 1, 2004 Date Department Program Amount Time Span Location Recipeint MP Present Tally All Government 6,830,827,550 Per Day 151,796,168 1-Apr-04 Industry TPC 7,200,000 Burnaby, BC Xantrex Technologies Hon. David Anderson 1-Apr-04 Industry TPC 9,500,000 Richmond, BC Sierra Wireless Hon. David Anderson 2-Apr-04 Industry TPC 9,360,000 London, ON Trojona Technologies Pat O'Brien 5-Apr-04 Industry Canada Research Chairs 121,600,000 Calgary, AB Hon. Lucienne Robillard 7-Apr-04 Industry TPC 3,900,000 Drumondville, PQ VisuAide Hon. Lucienne Robillard 7-Apr-04 Industry TPC 5,600,000 Montreal, PQ Fermag Hon. Lucienne Robillard 13-Apr-04 Industry 75,000,000 Quebec, PQ Genome Canada Hon. Lucienne Robillard 26-Apr-04 Industry TPC 3,760,000 Vancouver, BC Offshore Systems Hon. David Anderson 28-Apr-04 Industry TPC 8,700,000 Vancouver, BC Honeywell ASCa Hon. David Anderson 3-May-04 Industry TPC 7,700,000 Ottawa, ON MetroPhotonics Eugene Bellemare 4-May-04 Industry TPC 7,500,000 Port Coquitlam, BC OMNEX Control; Systems Hon. David Anderson 6-May-04 Industry TPC 4,600,000 Kanata, ON Cloakware Corporation Hon. David Pratt 7-May-04 Industry TPC 4,000,000 Waterloo, ON Raytheon Canada Limited Hon. Andrew Telegdi 7-May-04 Industry TPC 6,000,000 Ottawa, ON Edgeware Computer Systems Hon. David Pratt 13-May-04 Industry Bill C-9 170,000,000 Ottawa, ON Hon. Pierre Pettigrew 14-May-04 Industry TPC 4,000,000 Brossard, PQ Adacel Ltd Hon. -

Wednesday, April 24, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 032 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, April 24, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1883 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, April 24, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [English] _______________ LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA Prayers Mr. Ken Epp (Elk Island, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, voters need accurate information to make wise decisions at election time. With _______________ one vote they are asked to choose their member of Parliament, select the government for the term, indirectly choose the Prime The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now Minister and give their approval to a complete all or nothing list of sing O Canada, which will be led by the hon. member for agenda items. Vancouver East. During an election campaign it is not acceptable to say that the [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] GST will be axed with pledges to resign if it is not, to write in small print that it will be harmonized, but to keep it and hide it once the _____________________________________________ election has been won. It is not acceptable to promise more free votes if all this means is that the status quo of free votes on private members’ bills will be maintained. It is not acceptable to say that STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS MPs will be given more authority to represent their constituents if it means nothing and that MPs will still be whipped into submis- [English] sion by threats and actions of expulsion. -

Ministerial Error and the Political Process: Is There a Duty to Resign? Stuart James Whitley

Ministerial Error and the Political Process: Is there a Duty to Resign? Stuart James Whitley, QC* In practice, it is seldom very hard to do one’s duty when one knows what it is. But it is sometimes exceedingly difficult to find this out. - Samuel Butler (1912) “First Principles” Note Books The honourable leader is engaged continuously in the searching of his (sic) duty. Because he is practicing the most powerful and most dangerous of the arts affecting, however humbly, the quality of life and the human search for meaning, he ought to have – if honourable, he has to have – an obsession with duty. What are his responsibilities? -Christopher Hodgkinson (1983) The Philosophy of Leadership Abstract: This article examines the nature of the duty to resign for error in the ministerial function. It examines the question of resignation as a democratic safeguard and a reflection of a sense of honour among those who govern. It concludes that there is a duty to resign for misleading Parliament, for serious personal misbehaviour, for a breach of collective responsibility, for serious mismanagement of the department for which they are responsible, and for violations of the rule of law. The obligation is owed generally to Parliament, and specifically to the Prime Minister, who has the constitutional authority in any event to dismiss a minister. The nature of the obligation is a constitutional convention, which can only be enforced by political action, though a breach of the rule of law is reviewable in the courts and may effectively disable a minister. There appears to be uneven historical support for the notion that ministerial responsibility includes the duty to resign for the errors of officials except in very narrow circumstances. -

Government Mismanagement: Minister Besieged

Contents Government Mismanagement: Minister Besieged An audit of the federal job-creation grant program reveals what has been described at best as sloppy bookkeeping. As the current Minister for the Department of Human Resources, Jane Stewart must defend not only her own political reputation but that of the entire Liberal government. This story reveals how ministers of the Crown become especially accountable to the general public, the media, and opposition forces whether or not they personally are responsible for perceived errors or mismanagement. This aspect of political noblesse oblige and the parliamentary tradition of not holding a minister responsible for policy and practices once he or she has left a particular portfolio highlight the degree of responsibility that elected government officials must assume in order that the integrity of the democratic process be protected. Introduction Allegations and Accountability Her Majestys Loyal Opposition Whos Responsible? The Patronage Issue Ghosts and Skeletons Creating Employment Discussion, Research, and Essay Questions Comprehensive News in Review Study Modules Using both the print and non-print material from various issues of News in Review, teachers and students can create comprehensive, thematic modules that are excellent for research purposes, independent assignments, and small group study. We recommend the stories indicated below for the universal issues they represent and for the archival and historic material they contain. Cigarette Smuggling: Beating the Tax, November 1993 Medicare: -

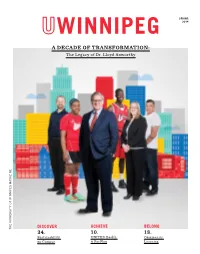

A DECADE of TRANSFORMATION —INSIDE & out the Legacy of Dr

SPRING WINNIPEG 2014 A DECADE OF TRANSFORMatION: The Legacy of Dr. Lloyd Axworthy DISCOVER ACHIEVE BELONG THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG MAGAZINE 34. 10. 18. Sustainability UNITED Health Community on Campus & RecPlex Learning Reward yourself. Get the BMO® University of Winnipeg MasterCard.®* Reward yourself with 1 AIR MILES®† reward mile for every $20 spent or 0.5% CashBack® and pay no annual fee1,2. Give something back With every purchase you make, BMO Bank of Montreal® makes a contribution to help support the development of programs and services for alumni, at no additional cost to you. Apply now! 1-800-263-2263 Alumni: bmo.com/winnipeg Student: bmo.com/winnipegspc Call 1-800-263-2263 to switch your BMO MasterCard to a BMO University of Winnipeg MasterCard. 1 Award of AIR MILES reward miles is made for purchases charged to your Account (less refunds) and is subject to the Terms and Conditions of your BMO MasterCard Cardholder Agreement. The number of reward miles will be rounded down to the nearest whole number. Fractions of reward miles will not be awarded. 2 Ongoing interest rates, interest-free grace period, annual fees and all other applicable fees are subject to change. See your branch, call the Customer Contact Center at 1-800-263-2263, or visit bmo.com/mastercard for current rates.® Registered trade-marks of Bank of Montreal. ®* MasterCard is a registered trademark of MasterCard International Incorporated. ®† Trademarks of AIR MILES International Trading B.V. Used under license by LoyaltyOne, Inc. and Bank of Montreal. Docket #: 13-321 Ad or Trim Size: 8.375" x 10.75" Publication: The Journal (Univ of Winnipeg FILE COLOURS: Type Safety: – Alumni Magazine) Description of Ad: U. -

Friday, April 27, 2001

CANADA VOLUME 137 S NUMBER 050 S 1st SESSION S 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, April 27, 2001 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 3241 56 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, April 27, 2001 The House met at 10 a.m. [English] _______________ The package has received positive support from health groups, such as the Canadian Cancer Society, the Heart and Stroke Prayers Foundation of Canada and the Alberta Tobacco Reduction Al- liance. _______________ My remarks today will focus on the new tax structure and tax D (1000) measures which are contained in amendments to the Customs Act, the Customs Tariff, the Excise Act, the Excise Tax Act and the MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE Income Tax Act. Before I discuss the individual measures in the bill, I would like to take a moment to put the legislation in The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a perspective. message has been received from the Senate informing this House that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of All tobacco products manufactured and sold in Canada have this House is desired. federal and provincial taxes and duties levied on them. Prior to 1994, tobacco products for export were sold on a tax free and duty _____________________________________________ free basis. In the early 1990s exports of Canadian cigarettes grew substan- GOVERNMENT ORDERS tially. There was strong evidence to suggest that most Canadian tobacco products that were illegally exported on a tax free and duty D (1005 ) free basis to the United States were being smuggled back into the country and sold illegally without the payment of federal and [English] provincial taxes.