ANDREEV and the PRACTICE of TRANSLATION in A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Drama Number 13 February Contents Leonid Andreyev, By

THE DRAMA Number 13 FEBRUARY CONTENTS E NID NDRE EV b Thomas S eltzer L O A Y , y THE PRE Y BINE WOMEN a com lete Drama TT SA , p h Leonid Andre ev in t ree acts, by y PE RE A PLA WRIGHT a review b SHAKES A S A Y , y George F ullmer Reyno lds E I LE THE TRE b Luc Fr n e Pierce TH L TT ST A , y y a c ILL MIN TI N AND THE DR M b Arthur U A O A A, y Pollock ’ B Y ND H UMAN P WER b e BJORNSON S E O O , y L e M ollander . H THE INDEPENDENCE DAY PAGEANT AT W HINGT N b E M S th l . m h A O , y e S it OS R WILDE G IN a revi w of rthur Ran CA A A , e A ’ som 8 scar Wilde A riti l b e O ; C ca S tudy, y Joseph Howard THE DR M LE GUE OF MERI 1914 A A A A CA, , by M A t rs. Starr B es THE TRI L HI ORY IN MERI 11 review A CA ST A CA , by Charlton Andrews A SELECTIVE LIST OF ESSAYS AND BOOKS BOUT THE THE TRE AND OF PL S ub A A AY , p : lished durin the fourth uarter of 1913 Fr k g q , by an Chouteau Brown THE DR A M A A Quarterly R eview of D ramatic Literature No . 13 February LEONID ANDREYEV . -

RUSSIAN THEATRE in the AGE of MODERNISM Also by Robert Russell

RUSSIAN THEATRE IN THE AGE OF MODERNISM Also by Robert Russell VALENTIN KATAEV V. MAYAKOVSKY, KLOP RUSSIAN DRAMA OF THE REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD YU.TRIFONOV,OBMEN Also by Andrew Barratt YURY OLESHA'S 'ENVY' BETWEEN TWO WORLDS: A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE MASTER AND MARGARITA A WICKED IRONY: THE RHETORIC OF LERMONTOV'S A HERO OF OUR TIME (with A. D. P. Briggs) Russian Theatre in the Age of Modernism Edited by ROBERT RUSSELL Senior Lecturer in Russian University of Sheffield and ANDREW BARRATT Senior Lecturer in Russian University of Otago Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-20751-0 ISBN 978-1-349-20749-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-20749-7 Editorial matter and selection © Robert Russell and Andrew Barratt 1990 Text © The Macmillan Press Ltd 1990 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1990 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1990 ISBN 978-0-312-04503-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russian theatre in the age of modernism / edited by Robert Russell and Andrew Barratt. p. em. ISBN 978-0-312-04503-6 1. Theater-Soviet Union-History-2Oth century. I. Russell, Robert, 1946-- . II. Barratt, Andrew. PN2724.R867 1990 792' .0947'09041--dc20 89-70291 OP Contents Preface vii Notes on the Contributors xii 1 Stanislavsky's Production of Chekhov's Three Sisters Nick Worrall 1 2 Boris Geyer and Cabaretic Playwriting Laurence Senelick 33 3 Boris Pronin, Meyerhold and Cabaret: Some Connections and Reflections Michael Green 66 4 Leonid Andreyev's He Who Gets Slapped: Who Gets Slapped? Andrew Barratt 87 5 Kuzmin, Gumilev and Tsvetayeva as Neo-Romantic Playwrights Simon Karlinsky 106 6 Mortal Masks: Yevreinov's Drama in Two Acts Spencer Golub 123 7 The First Soviet Plays Robert Russell 148 8 The Nature of the Soviet Audience: Theatrical Ideology and Audience Research in the 1920s Lars Kleberg 172 9 German Expressionism and Early Soviet Drama Harold B. -

Zalman Shneour and Leonid Andreyev, David Vogel and Peter Altenberg Lilah Nethanel Bar-Ilan University

Hidden Contiguities: Zalman Shneour and Leonid Andreyev, David Vogel and Peter Altenberg Lilah Nethanel Bar-Ilan University abstract: The map of modern Jewish literature is made up of contiguous cultural environments. Rather than a map of territories, it is a map of stylistic and conceptual intersections. But these intersections often leave no trace in a translation, a quotation, a documented encounter, or an archived correspondence. We need to reconsider the mapping of modern Jewish literature: no longer as a defined surface divided into ter- ritories of literary activity and publishing but as a dynamic and often implicit set of contiguities. Unlike comparative research that looks for the essence of literary influ- ence in the exposure of a stylistic or thematic similarity between works, this article discusses two cases of “hidden contiguities” between modern Jewish literature and European literature. They occur in two distinct contact zones in which two European Jewish authors were at work: Zalman Shneour (Shklov, Belarus, 1887–New York, 1959), whose early work, on which this article focuses, was done in Tsarist Russia; and David Vogel (Podolia, Russia, 1891–Auschwitz, 1944), whose main work was done in Vienna after the First World War. rior to modern jewish nationalism becoming a pragmatic political organization, modern Jewish literature arose as an essentially nonsovereign literature. It embraced multinational contexts and was written in several languages. This literature developed Pin late nineteenth-century Europe on a dual basis: it expressed the immanent national founda- tions of a Jewish-national renaissance, as well as being deeply inspired by the host environment. It presents a fascinating case study for recent research on transnational cultures, since it escapes any stable borderline and instead manifests conflictual tendencies of disintegration and reinte- gration, enclosure and permeability, outreach and localism.1 1 Emily S. -

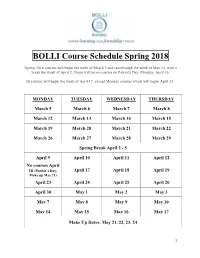

BOLLI Course Schedule Spring 2018

BOLLI Course Schedule Spring 2018 Spring 2018 courses will begin the week of March 5 and run through the week of May 14, with a break the week of April 2. There will be no courses on Patriot's Day, Monday, April 16. 5b courses will begin the week of April 17, except Monday courses which will begin April 23. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY March 5 March 6 March 7 March 8 March 12 March 13 March 14 March 15 March 19 March 20 March 21 March 22 March 26 March 27 March 28 March 29 Spring Break April 2 - 5 April 9 April 10 April 11 April 12 No courses April 16 (Patriot’s Day- April 17 April 18 April 19 Make up May 21) April 23 April 24 April 25 April 26 April 30 May 1 May 2 May 3 May 7 May 8 May 9 May 10 May 14 May 15 May 16 May 17 Make Up Dates: May 21, 22, 23, 24 1 Monday BOLLI Study Groups Spring 2018 Period 1 MUS1-10-Mon1 LIT4-10-Mon1 LIT5-5b-Mon1 SOC5-10-Mon1 9:30 a.m.-10:55 a.m. Beyond Hava Nagila: Whodunit? Murder in Existentialism at the Manipulation: How What is Jewish Ethnic Communities Café Hidden Influences Music? Affect Our Choice of Marilyn Brooks Jennifer Eastman Products, Politicians Sandy Bornstein and Priorities 5 Week Course – April 23 – May 21 Sandy Sherizen Period 2 MUS3-10-Mon2 LIT8-10-Mon2 SOC2-5a-Mon2 WRI1-10-Mon2 11:10 a.m. - 12:35 Why Sing Plays? An Historical Fiction: Childhood In the Writing to Discover: A p.m. -

Freedom from Violence and Lies Essays on Russian Poetry and Music by Simon Karlinsky

Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky simon Karlinsky, early 1970s Photograph by Joseph Zimbrolt Ars Rossica Series Editor — David M. Bethea (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky edited by robert P. Hughes, Thomas a. Koster, richard Taruskin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-158-6 On the cover: Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957), Bayerische Landschaft mit Fuhrwerk (ca. 1918). Oil on panel. In Simon Karlinsky’s collection, 1946–2009. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

'Determined to Be Weird': British Weird Fiction Before Weird Tales

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Birkbeck, University of London ‘Determined to be Weird’: British Weird Fiction before Weird Tales James Fabian Machin Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 1 Declaration I, James Fabian Machin, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signature_______________________________________ Date____________________ 2 Abstract Weird fiction is a mode in the Gothic lineage, cognate with horror, particularly associated with the early twentieth-century pulp writing of H. P. Lovecraft and others for Weird Tales magazine. However, the roots of the weird lie earlier and late-Victorian British and Edwardian writers such as Arthur Machen, Count Stenbock, M. P. Shiel, and John Buchan created varyingly influential iterations of the mode. This thesis is predicated on an argument that Lovecraft’s recent rehabilitation into the western canon, together with his ongoing and arguably ever-increasing impact on popular culture, demands an examination of the earlier weird fiction that fed into and resulted in Lovecraft’s work. Although there is a focus on the literary fields of the fin de siècle and early twentieth century, by tracking the mutable reputations and critical regard of these early exponents of weird fiction, this thesis engages with broader contextual questions of cultural value and distinction; of notions of elitism and popularity, tensions between genre and literary fiction, and the high/low cultural divide allegedly precipitated by Modernism. 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: The Wyrd, the Weird-like, and the Weird .............................. -

Amherst Center for Russian Culture

AMHERST CENTER FOR RUSSIAN CULTURE The Andreyev Family Papers 1960s-1970s Summary: The Andreyev Family Papers consist of manuscripts, diaries and poems written by members of the family of Leonid Andreyev, including works by his sons Vadim and Daniil Andreyev, daughter-in-law Olga Chernov and granddaughter Olga Carlisle. Quantity: 1.00 linear foot Containers: 1 record storage box Processed: November 2012 By: Ethan Gates Stanley Rabinowitz Listed: By: Finding Aid: November 2012 Prepared by: Ethan Gates, Russian Center Assistant Edited by: Stanley Rabinowitz, Director, Center for Russian Culture Access: There is no restriction on access to the Andreyev Family Papers for research use. Particularly fragile items may be restricted for preservation purposes. Copyright: Requests for permission to publish from the Andreyev Family Papers should be sent to the Director of the Amherst Center for Russian Culture. It is the responsibility of the researcher to identify and satisfy the holders of all copyrights. © 2012 Amherst Center for Russian Culture Page 1 The Andreyev Family Papers INTRODUCTION Historical Note Leonid Andreyev (1871-1919) was a prominent playwright and novelist of the early 20th century. Though he gained much popularity and was considered a major social and political thinker around the time of the first (1905) Russian revolution, by 1917 his influence had waned. He moved to Finland to avoid the rise of the Bolsheviks, whom Andreyev bitterly opposed. In 1919 he died of heart failure. Both Andreyev’s sons became well-known writers in their own right. His older son, Vadim (1902-1975), spent most of his life first in Berlin and later Paris, where he was a respected emigré poet. -

Leo Tolstoy and Writers of World Literature Literary Reflections - Elchin Efendiyev

Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 23 № 3 2020, 100-112 © Khazar University Press 2020 DOI: 10.5782/2223-2621.2020.23.3.100 Leo Tolstoy And Writers of World Literature Literary Reflections - Elchin Efendiyev Gulnara Hasanova Baku Slavic University, Baku, Azerbaijan. [email protected] Abstract It is a study of literary interaction questions and the identification of mutual enrichment patterns that currently acquire particular significance. The concept of foreign literary experience becomes ever more profound and diverse and is realized by a creative rethinking (not imitation or adoption) of another literature's achievements. This paper aims to identify the profound influence of world literature on Tolstoy and vice-versa: the influence his creative works had on European literature. The paper shows the need to study the originality of Tolstoy’s artistic legacy's foreign reception and, therefore, complement the overall picture of perception and functioning of the writer’s creation in the foreign literary context and cultural environment. The study of this theme is very significant from the standpoint of modern globalization, dialogue between cultures. The novelty here lies in the fact that the question of how Tolstoy’s works have been received within the context of creative cross- cultural dialogue has not been given sufficient attention within international comparative studies. There is no systematizing and summarizing research in the national science about a writer’s perception and peculiarities of appraisal of writer’s works involving the Azerbaijani studies material, drawing parallels with the national literature. For this consideration of Tolstoy’s work, the conception of Azerbaijani prose writing is taken to represent a World literary context. -

LEONID ANDREYEV's VERBAL and VISUAL IMAGERY Patrick Wise An

Wise 1 “SMOOTHLY GLIDING IMAGES”: LEONID ANDREYEV’S VERBAL AND VISUAL IMAGERY Patrick Wise An honors thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2017 Shayne Legassie Stanislav Shvabrin Wise 2 Acknowledgements This project has been an exhilarating experience. I would like to thank first and foremost Professor Stanislav Shvabrin for his continuous support and help with this project. I also must thank Dr. Shvabrin for introducing me to Leonid Andreyev and inspiring me to continue my investigation of his work. I additionally would like to extend my deep appreciation to Dr. Shayne Legassie, who graciously agreed to advise me in this project from the Comparative Literature side of the aisle, and furthermore suggested that I undertake an Honors thesis in the first place. Without that validation, I doubt that I would have ever thought myself capable of undertaking such a project. Furthermore, I must thank Dr. Radislav Lapushin for joining my thesis committee and rounding out a triumvirate of excellent professors. I owe a large debt to my good friend Benjamin Brindis for his aid in the revision process, as well as his willingness to send emails in Russian to the Andreyev House Museum in an attempt to acquire a few high quality images of Andreyev’s visual work. Finally, I want to thank Karissa Barrera for her unending emotional and intellectual support throughout this entire -

Satan's Diary

Satan's Diary SATAN'S DIARY BY LEONID ANDREYEV Authorized Translation WITH A PREFACE BY HERMAN BERNSTEIN BONI AND LIVERIGHT PUBLISHERS NEW YORK COPYRIGHT, 1920, BT BONI & LIVERIGHT, INC. /B 8 9 fl ? 1 1 Printed in (As t/ntted Sfotej o/ America PREFACE DIARY," Leonid Andreyev's last work, was completed by the great Russian a SATAN'Sfew days before lie died in Finland, in Sep- tember, 1919. But a few years ago the most pop- ular and successful of Russian writers, Andreyev died almost penniless, a sad, tragic figure, disil- lusioned, broken-hearted over the tragedy of Russia. A year ago Leonid Andreyev wrote me that he was eager to come to America, to study this coun- try and familiarize Americans with the fate of his unfortunate countrymen. I arranged for his visit to this country and informed him of this by cable. But on the very day I sent my cable the sad news came from Finland announcing that Leonid An- died of heart failure. dreyev" In Satan's Diary" Andreyev summed up his boundless disillusionment in an absorbing satire on human life. Fearlessly and mercilessly he hurled the falsehoods and hypocrisies into the face of life. He portrayed Satan coming to this earth to amuse himself and play. Having as- sumed the form of an American multi-millionaire, Satan set out on a tour through Europe in quest of amusement and adventure. Before him passed various forms of spurious virtues, hypocrisies, Preface the ruthless cruelty of man and the often deceptive innocence of woman. Within a short time Satan finds himself outwitted, deceived, relieved of his millions, mocked, humiliated, beaten by man in his own devilish devices. -

The Real Face of Russia

THE REAL FACE OF RUSSIA ESSAYS AND ARTICLES UKRAINIAN INFORMATION SERVICE THE REAL FACE OF RUSSIA THE REAL FACE OF RUSSIA ESSAYS AND ARTICLES EDITED BY VOLODYMYR BOHDANIUK, B.A., B.Litt. UKRAINIAN INFORMATION SERVICE LONDON 1967 PUBLISHED BY UKRAINIAN INFORMATION SERVICE 200, Liverpool Rd., London, N.l. 1967 Printed in Great Britain by Ukrainian Publishers Limited, 200, Liverpool Rd., London, N.l. Tel. 01-607-6266/7 CONTENTS Page PREFACE ................................................................................................. 7 THE SPIRIT OF RUSSIA by Dr. Dmytro Donzow .............................................. 9 ON THE PROBLEM OF BOLSHEVISM by Evhen M alaniuk ...................................................... 77 THE RUSSIAN HISTORICAL ROOTS OF BOLSHEVISM by Professor Yuriy Boyko .............................................. 129 THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF RUSSIAN IMPERIALISM by Dr. Baymirza H ayit .............................................. 149 BOLSHEVISM AND INTERNATIONALISM by Olexander Yourchenko ..................................... 171 THE “SCIENTIFIC” CHARACTER OF DIALECTICAL MATERIALISM by U. Kuzhil ............................................................... 187 THE HISTORICAL NECESSITY OF THE DISSOLUTION OF THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE by Prince Niko Nakashidze ..................................... 201 UKRAINIAN LIBERATION STRUGGLE by Professor Lev Shankowsky ............................. 211 THE ROAD TO FREEDOM AND THE END OF FEAR by Jaroslav Stetzko ...................................................... 233 TWO -

Savva and the Life of Man

Savva and The Life of Man Leonid Andreyev The Project Gutenberg EBook of Savva and The Life of Man, by Leonid Andreyev This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Savva and The Life of Man Author: Leonid Andreyev Release Date: August 9, 2004 [EBook #13147] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SAVVA AND THE LIFE OF MAN *** Produced by David Starner, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THE MODERN DRAMA SERIES EDITED BY EDWIN BJOeRKMAN SAVVA THE LIFE OF MAN BY LEONID ANDREYEV SAVVA THE LIFE OF MAN TWO PLAYS BY Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. LEONID ANDREYEV TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY THOMAS SELTZER BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY 1920 1914, BY LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY. _This edition is authorized by Leonid Andreyev, who has selected the plays included in it._ _All Dramatic rights reserved by Edwin Bjoerkman_ CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF PLAYS BY LEONID ANDREYEV SAVVA THE LIFE OF MAN INTRODUCTION For the last twenty years Leonid Andreyev and Maxim Gorky have by turns occupied the centre of the stage of Russian literature. Prophetic vision is no longer required for an estimate of their permanent contribution to the intellectual and literary development of Russia. It represents the highest ideal expression of a period in Russian history that was pregnant with stirring and far-reaching events--the period of revolution and counter-revolution.