In the Spring Quarter of 1946 I Returned from the War to Long-Awaited Civilian Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

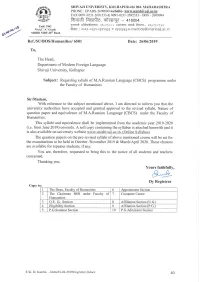

M.A. Russian 2019

************ B+ Accredited By NAAC Syllabus For Master of Arts (Part I and II) (Subject to the modifications to be made from time to time) Syllabus to be implemented from June 2019 onwards. 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Revised Syllabus For Master of Arts 1. TITLE : M.A. in Russian Language under the Faculty of Arts 2. YEAR OF IMPLEMENTATION: New Syllabus will be implemented from the academic year 2019-20 i.e. June 2019 onwards. 3. PREAMBLE:- 4. GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE: 1) To arrive at a high level competence in written and oral language skills. 2) To instill in the learner a critical appreciation of literary works. 3) To give the learners a wide spectrum of both theoretical and applied knowledge to equip them for professional exigencies. 4) To foster an intercultural dialogue by making the learner aware of both the source and the target culture. 5) To develop scientific thinking in the learners and prepare them for research. 6) To encourage an interdisciplinary approach for cross-pollination of ideas. 5. DURATION • The course shall be a full time course. • The duration of course shall be of Two years i.e. Four Semesters. 6. PATTERN:- Pattern of Examination will be Semester (Credit System). 7. FEE STRUCTURE:- (as applicable to regular course) i) Entrance Examination Fee (If applicable)- Rs -------------- (Not refundable) ii) Course Fee- Particulars Rupees Tuition Fee Rs. Laboratory Fee Rs. Semester fee- Per Total Rs. student Other fee will be applicable as per University rules/norms. 8. IMPLEMENTATION OF FEE STRUCTURE:- For Part I - From academic year 2019 onwards. -

Vol. 73, No. 7JULY/AUGUST 1968 Published•By Conway Hall

Vol. 73, No. 7JULY/AUGUST 1968 CONTENTS Eurnmum..• 3 "ULYSSES": THE BOOK OF THE FILM . 5 by Ronald Mason THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF RELIGION . 8 by Dr. H. W. Turner JEREMY BENTFIAM .... 10 by Maurice Cranston, MA MAXIM GORKY•••• • 11 by Richard Clements, aRE. BOOK REVIEW: Gown. FORMutEncs. 15 by Leslie Johnson WHO SAID THAT? 15 Rum THE SECRETARY 16 TO THE EDITOR . 17 PEOPLEOUT OF 11113NEWS 19 DO SOMETHINGNICE FOR SOMEONE 19 SOUTH PLACENaws. 20 Published•by Conway Hall Humanist Centre Red Um Square, London, Wel SOUTH PLACE ETHICAL SOCIETY Omens: Secretary: Mr. H. G. Knight Hall Manager and Lettings Secretary: Miss E. Palmer Hon. Registrar: Miss E. Palmer Hon. Treasurer: Mr. W. Bynner Editor, "The Ethical Record": Miss Barbara Smoker Address: Conway Hall Humanist Centre, Red Lion Square, London, W.C.I (Tel.: CHAncery 8032) SUNDAY MORNING MEETINGS, II a.rn. (Admission free) July 7—Lord SORENSEN Ivory Towers Soprano solos: Laura Carr. July 14—J. STEWART COOK. BSc. Politics and Reality Cello and piano: Lilly Phillips and Fiona Cameron July 21—Dr. JOHN LEWIS The Students' Revolt Piano: Joyce Langley SUNDAY MORNING MEETINGS are then suspended until October 6 S.P.E.S. ANNUAL REUNION Sunday, September 29, 1968, 3 p.m. in the Large Hall at CONWAY HUMANIST CENTRE Programme of Music (3 p.m.) Speeches by leaders of Humanist organisations (3.30 P.m.) Guest of Honour: LORD WILLIS Buffet Tea (5 p.m.) Tickets free from General Secretary CONWAY DISCUSSIONS will resume on Tuesdays at 6.45 p.m. from October 1 The 78th season of SOUTH PLACE SUNDAY CONCERTS will open on October 6 at 6.30 p.m. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

The Arts in Russia Under Stalin

01_SOVMINDCH1. 12/19/03 11:23 AM Page 1 THE ARTS IN RUSSIA UNDER STALIN December 1945 The Soviet literary scene is a peculiar one, and in order to understand it few analogies from the West are of use. For a vari- ety of causes Russia has in historical times led a life to some degree isolated from the rest of the world, and never formed a genuine part of the Western tradition; indeed her literature has at all times provided evidence of a peculiarly ambivalent attitude with regard to the uneasy relationship between herself and the West, taking the form now of a violent and unsatisfied longing to enter and become part of the main stream of European life, now of a resentful (‘Scythian’) contempt for Western values, not by any means confined to professing Slavophils; but most often of an unresolved, self-conscious combination of these mutually opposed currents of feeling. This mingled emotion of love and of hate permeates the writing of virtually every well-known Russian author, sometimes rising to great vehemence in the protest against foreign influence which, in one form or another, colours the masterpieces of Griboedov, Pushkin, Gogol, Nekrasov, Dostoevsky, Herzen, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Blok. The October Revolution insulated Russia even more com- pletely, and her development became perforce still more self- regarding, self-conscious and incommensurable with that of its neighbours. It is not my purpose to trace the situation histori- cally, but the present is particularly unintelligible without at least a glance at previous events, and it would perhaps be convenient, and not too misleading, to divide its recent growth into three main stages – 1900–1928; 1928–1937; 1937 to the present – artifi- cial and over-simple though this can easily be shown to be. -

Socialist Realism Seen in Maxim Gorky's Play The

SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i ii iii HHaappppiinneessss aallwwaayyss llooookkss ssmmaallll wwhhiillee yyoouu hhoolldd iitt iinn yyoouurr hhaannddss,, bbuutt lleett iitt ggoo,, aanndd yyoouu lleeaarrnn aatt oonnccee hhooww bbiigg aanndd pprreecciioouuss iitt iiss.. (Maxiim Gorky) iv Thiis Undergraduatte Thesiis iis dediicatted tto:: My Dear Mom and Dad,, My Belloved Brotther and Siistters.. v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to praise Allah SWT for the blessings during the long process of this undergraduate thesis writing. I would also like to thank my patient and supportive father and mother for upholding me, giving me adequate facilities all through my study, and encouragement during the writing of this undergraduate thesis, my brother and sisters, who are always there to listen to all of my problems. I am very grateful to my advisor Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S.S., M.Hum. for helping me doing my undergraduate thesis with his advice, guidance, and patience during the writing of my undergraduate thesis. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. -

Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat"

Swarthmore College Works Russian Faculty Works Russian 2008 "Mother", As Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia's "Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat" Sibelan E.S. Forrester Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Sibelan E.S. Forrester. (2008). ""Mother", As Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia's "Sof'ia Petrovna" Rewrites Maksim Gor'kii's "Mat"". American Contributions to the 14th International Congress of Slavists: Ohrid 2008. Volume 2, 51-67. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-russian/249 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mother as Forebear: How Lidiia Chukovskaia’s Sof´ia Petrovna Rewrites Maksim Gor´kii’s Mat´* Sibelan E. S. Forrester Lidiia Chukovskaia’s novella Sof´ia Petrovna (henceforth abbreviated as SP) has gained a respectable place in the canon of primary sources used in the United States to teach about the Soviet period,1 though it may appear on history syllabi more often than in (occasional) courses on Russian women writers or (more common) surveys of Russian or Soviet literature. The tendency to read and use the work as a historical document begins with the author herself: Chukovskaia consistently emphasizes its value as a testimonial and its uniqueness as a snapshot of the years when it was writ- ten. -

The Drama Number 13 February Contents Leonid Andreyev, By

THE DRAMA Number 13 FEBRUARY CONTENTS E NID NDRE EV b Thomas S eltzer L O A Y , y THE PRE Y BINE WOMEN a com lete Drama TT SA , p h Leonid Andre ev in t ree acts, by y PE RE A PLA WRIGHT a review b SHAKES A S A Y , y George F ullmer Reyno lds E I LE THE TRE b Luc Fr n e Pierce TH L TT ST A , y y a c ILL MIN TI N AND THE DR M b Arthur U A O A A, y Pollock ’ B Y ND H UMAN P WER b e BJORNSON S E O O , y L e M ollander . H THE INDEPENDENCE DAY PAGEANT AT W HINGT N b E M S th l . m h A O , y e S it OS R WILDE G IN a revi w of rthur Ran CA A A , e A ’ som 8 scar Wilde A riti l b e O ; C ca S tudy, y Joseph Howard THE DR M LE GUE OF MERI 1914 A A A A CA, , by M A t rs. Starr B es THE TRI L HI ORY IN MERI 11 review A CA ST A CA , by Charlton Andrews A SELECTIVE LIST OF ESSAYS AND BOOKS BOUT THE THE TRE AND OF PL S ub A A AY , p : lished durin the fourth uarter of 1913 Fr k g q , by an Chouteau Brown THE DR A M A A Quarterly R eview of D ramatic Literature No . 13 February LEONID ANDREYEV . -

RUSSIAN THEATRE in the AGE of MODERNISM Also by Robert Russell

RUSSIAN THEATRE IN THE AGE OF MODERNISM Also by Robert Russell VALENTIN KATAEV V. MAYAKOVSKY, KLOP RUSSIAN DRAMA OF THE REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD YU.TRIFONOV,OBMEN Also by Andrew Barratt YURY OLESHA'S 'ENVY' BETWEEN TWO WORLDS: A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE MASTER AND MARGARITA A WICKED IRONY: THE RHETORIC OF LERMONTOV'S A HERO OF OUR TIME (with A. D. P. Briggs) Russian Theatre in the Age of Modernism Edited by ROBERT RUSSELL Senior Lecturer in Russian University of Sheffield and ANDREW BARRATT Senior Lecturer in Russian University of Otago Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-20751-0 ISBN 978-1-349-20749-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-20749-7 Editorial matter and selection © Robert Russell and Andrew Barratt 1990 Text © The Macmillan Press Ltd 1990 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1990 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1990 ISBN 978-0-312-04503-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russian theatre in the age of modernism / edited by Robert Russell and Andrew Barratt. p. em. ISBN 978-0-312-04503-6 1. Theater-Soviet Union-History-2Oth century. I. Russell, Robert, 1946-- . II. Barratt, Andrew. PN2724.R867 1990 792' .0947'09041--dc20 89-70291 OP Contents Preface vii Notes on the Contributors xii 1 Stanislavsky's Production of Chekhov's Three Sisters Nick Worrall 1 2 Boris Geyer and Cabaretic Playwriting Laurence Senelick 33 3 Boris Pronin, Meyerhold and Cabaret: Some Connections and Reflections Michael Green 66 4 Leonid Andreyev's He Who Gets Slapped: Who Gets Slapped? Andrew Barratt 87 5 Kuzmin, Gumilev and Tsvetayeva as Neo-Romantic Playwrights Simon Karlinsky 106 6 Mortal Masks: Yevreinov's Drama in Two Acts Spencer Golub 123 7 The First Soviet Plays Robert Russell 148 8 The Nature of the Soviet Audience: Theatrical Ideology and Audience Research in the 1920s Lars Kleberg 172 9 German Expressionism and Early Soviet Drama Harold B. -

Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial Board T

GUIDE Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial board T. Liptuga, G. Zakipnaya, G. Semykina, A. Yavorskaya Authors A. Yavorskaya, G. Semykina, Y. Karakina, G. Zakipnaya, L. Melnichenko, A. Bozhko, L. Liputa, M. Kotelnikova, I. Savrasova English translation O. Voronina Photo Georgiy Isayev, Leonid Sidorsky, Andrei Rafael О417 Одеський літературний музей : Путівник / О. Яворська та ін. Ред. кол. : Т. Ліптуга та ін., – Фото Г. Ісаєва та ін. – Одеса, 2017. – 160 с.: іл. ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 Odessa Literary Museum: Guide / A.Yavorskaya and others. Editorial: T. Liptuga and others, - Photo by G.Isayev and others. – Odessa, 2017. — 160 p.: Illustrated Guide to the Odessa Literary Museum is a journey of more than two centuries, from the first years of the city’s existence to our days. You will be guided by the writers who were born or lived in Odessa for a while. They created a literary legend about an amazing and unique city that came to life in the exposition of the Odessa Literary Museum UDC 069:801 (477.74) Англійською мовою ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 © OLM, 2017 INTRODUCTION The creators of the museum considered it their goal The open-air exposition "The Garden of Sculptures" to fill the cultural lacuna artificially created by the ideo- with the adjoining "Odessa Courtyard" was a successful logical policy of the Soviet era. Despite the thirty years continuation of the main exposition of the Odessa Literary since the opening day, the exposition as a whole is quite Museum. The idea and its further implementation belongs he foundation of the Odessa Literary Museum was museum of books and local book printing and the history modern. -

Zalman Shneour and Leonid Andreyev, David Vogel and Peter Altenberg Lilah Nethanel Bar-Ilan University

Hidden Contiguities: Zalman Shneour and Leonid Andreyev, David Vogel and Peter Altenberg Lilah Nethanel Bar-Ilan University abstract: The map of modern Jewish literature is made up of contiguous cultural environments. Rather than a map of territories, it is a map of stylistic and conceptual intersections. But these intersections often leave no trace in a translation, a quotation, a documented encounter, or an archived correspondence. We need to reconsider the mapping of modern Jewish literature: no longer as a defined surface divided into ter- ritories of literary activity and publishing but as a dynamic and often implicit set of contiguities. Unlike comparative research that looks for the essence of literary influ- ence in the exposure of a stylistic or thematic similarity between works, this article discusses two cases of “hidden contiguities” between modern Jewish literature and European literature. They occur in two distinct contact zones in which two European Jewish authors were at work: Zalman Shneour (Shklov, Belarus, 1887–New York, 1959), whose early work, on which this article focuses, was done in Tsarist Russia; and David Vogel (Podolia, Russia, 1891–Auschwitz, 1944), whose main work was done in Vienna after the First World War. rior to modern jewish nationalism becoming a pragmatic political organization, modern Jewish literature arose as an essentially nonsovereign literature. It embraced multinational contexts and was written in several languages. This literature developed Pin late nineteenth-century Europe on a dual basis: it expressed the immanent national founda- tions of a Jewish-national renaissance, as well as being deeply inspired by the host environment. It presents a fascinating case study for recent research on transnational cultures, since it escapes any stable borderline and instead manifests conflictual tendencies of disintegration and reinte- gration, enclosure and permeability, outreach and localism.1 1 Emily S. -

Repertoire for October 2018

REPERTOIRE FOR OCTOBER 2018. MAIN STAGE season “RAŠA PLAOVIĆ” STAGE 2018/19. THU. IVANOV MON. BALKAN SPY / PREMIERE 11. 7.30pm drama by A.P. Chekhov 01.8.30pm drama by Dušan Kovačević WEN. NATIONAL DAY OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA TUE. BALKAN SPY 31. 7.30pm 02.8.30pm drama by Dušan Kovačević WEN. BALKAN SPY 03.8.30pm drama by Dušan Kovačević THU. STUDENTS IN LOVE 04.8.00pm recital organized by the Dositej Obradović Foundation FRI. VOLUME TWO 05.8.30pm drama by Branislav Nušić OPERA & THEATRE MADLENIANUM SAT. THE MARRIAGE 06.8.30pm comedy by N. Gogol (Tickets can be purchased at the MADLENIANUM box o ce) MON. SUN. THE SEXUAL NEUROSES OF OUR PARENTS 08. 7.30pm 07.8.30pm drama by Lukas Barfuss FRI. CARMEN MON. BIZARRE 19. 7.30pm opera by Georges Bizet 08.8.30pm black comedy by Željko Hubač WEN. LA TRAVIATA TUE. COFFEE WHITE 24. 7.30pm opera by Giuseppe Verdi 09.8.30pm comedy by Aleksandar Popović SAT. DON UIXOTE WEN. THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST 27. 7.30pm ballet by Ludwig Minkus 10.8.30pm comedy by Oscar Wilde SUN. THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO FRI. XXII FESTIVAL OF CHOREOGRAPHIC MINIATURES 28. 7.30pm opera by W.A. Mozart 12.2.00pm Selection of the nalists (free entrance) MON. DICTIONARY OF THE KHAZARS – DREAM HUNTERS SAT. XXII FESTIVAL OF CHOREOGRAPHIC MINIATURES 29. 7.30pm ballet a er the novel by Milorad Pavić, coproduction with the Opera & eatre Madlenianum 13.8.00pm Finalists of Competition Program IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA SUN. -

Download Download

The Liberal Imagination in The Middle of the Journey Christopher Phelps When Lionel Trilling's first and only novel, The Middle of the Journey, was published in 1947, the circle of writers and cultural critics with whom he had long been associated was near the completion of its political transformation from anti-Stalinist radicalism to anti-communist liberalism. Only ten years before, most of these figures, yet to reach their self-anointed destiny as "the New York intellectuals," had been revolutionary socialists. Following a momentary association with Communism in the early thirties, they had become outspoken opponents of the bureaucratic despotism that had over- taken the global Communist movement, all the while upholding Marxism and retaining their opposition to imperialism and capitalism. By the late 1940s, however, a succession of international disasters - the Moscow trials, the Hitler-Stalin pact, the Second World War and the emergent Cold War, as well as the toll exacted over time by the condition of marginality to which revolu- tionary anti-Stalinists were relegated - had unmoored the New York intel- lectuals, with few exceptions, from their commitment to the liberation of the working class and the abolition of capitalism. The Middle of the Journey appeared at that unique moment in postwar intellectual history when the New York intellectuals' attachment to revolutionary aims had been severed but their ultimate course was not yet altogether fixed. If the mid-1940s were somewhat fluid, by the early 1950s the New York intellectuals were the practitioners of a suave, disappointed liberalism. Although they continued to refer to themselves as the "anti-Stalinist left," or part of it, their politics became ever more narrowly liberal as they ceased to distinguish between the worldview of Marxism, or the social ideal of commu- nism, and the reality of Stalinism.