PDF (Volume 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF the Migration of Literary Ideas: the Problem of Romanian Symbolism

The Migration of Literary Ideas: The Problem of Romanian Symbolism Cosmina Andreea Roșu ABSTRACT: The migration of symbolists’ ideas in Romanian literary field during the 1900’s occurs mostly due to poets. One of the symbolist poets influenced by the French literature (the core of the Symbolism) and its representatives is Dimitrie Anghel. He manages symbols throughout his entire writings, both in poetry and in prose, as a masterpiece. His vivid imagination and fantasy reinterpret symbols from a specific Romanian point of view. His approach of symbolist ideas emerges from his translations from the French authors but also from his original writings, since he creates a new attempt to penetrate another sequence of the consciousness. Dimitrie Anghel learns the new poetics during his years long staying in France. KEY WORDS: writing, ideas, prose poem, symbol, fantasy. A t the beginning of the twentieth century the Romanian literature was dominated by Eminescu and his epigones, and there were visible effects of Al. Macedonski’s efforts to impose a new poetry when Dimitrie Anghel left to Paris. Nicolae Iorga was trying to initiate a new nationalist movement, and D. Anghel was blamed for leaving and detaching himself from what was happening“ in the” country. But “he fought this idea in his texts making ironical remarks about those“The Landwho were” eagerly going away from native land ( Youth – „Tinereță“, Looking at a Terrestrial Sphere” – „Privind o sferă terestră“, a literary – „Pământul“). Babel tower He settled down for several years in Paris, which he called 140 . His work offers important facts about this The Migration of Literary Ideas: The Problem of Romanian Symbolism 141 Roșu: period. -

Poems of Ossian

0/», IZ*1. /S^, £be Canterbury fl>oets. Edited by William Sharp. POEMS OF OSSIAN. SQ OEMS OF CONTENTS. viii CONTENTS. PAGE Cathlin of Clutha: a Poem . .125 sub-malla of lumon : a poem . 135 The War of Inis-thona : a Poem 4.3 The Songs of Selma . 151 Fingal: an Ancient Epic Poem- I. Book . .163 Book II. 183 Book III. .197 Book IV. .... 213 Book V. 227 Book VI. ..... 241 Lathmon : a Poem .... 255 \Dar-Thula : a Poem . .271 The Death of Cuthullin : a Poem . 289 INTRODUCTION. ROM the earliest ages mankind have been lovers of song and tale. To their singers in times of old men looked for comfort in sorrow, for inspiration in battle, and for renown after death. Of these singers were the prophets of Israel, the poets and rhapsodes of ancient Greece, the skalds of the Scandinavian sea-kings, and the bards of the Celtic race. The office was always most honour- able, the bard coming next the hero in esteem ; and thus, first of the fine arts, was cultivated the art of song. Down to quite a recent time the household of no Highland chief was complete without its bard, to sing the great deeds of the race's ancestors. And to the present day, though the locomotive and the printing press have done much to kill these customs of a more heroic age, it is not difficult to find in the Highland glens those who can still recite a " tale of the times of old." x INTRODUCTION. During the troubles of the Reformation in the sixteenth century, of the Civil Wars .and Revolu- tion in the seventeenth, and of the Parliamentary Union and Jacobite Rebellions in the early part of the eighteenth, the mind of Scotland was entirely engrossed with politics, and the Highlands them- selves were continually unsettled. -

Songfest 2008 Book of Words

A Book of Words Created and edited by David TriPPett SongFest 2008 A Book of Words The SongFest Book of Words , a visionary Project of Graham Johnson, will be inaugurated by SongFest in 2008. The Book will be both a handy resource for all those attending the master classes as well as a handsome memento of the summer's work. The texts of the songs Performed in classes and concerts, including those in English, will be Printed in the Book . Translations will be Provided for those not in English. Thumbnail sketches of Poets and translations for the Echoes of Musto in Lieder, Mélodie and English Song classes, comPiled and written by David TriPPett will enhance the Book . With this anthology of Poems, ParticiPants can gain so much more in listening to their colleagues and sharing mutually in the insights and interPretative ideas of the grouP. There will be no need for either ParticiPating singers or members of the audience to remain uninformed concerning what the songs are about. All attendees of the classes and concerts will have a significantly greater educational and musical exPerience by having word-by-word details of the texts at their fingertiPs. It is an exciting Project to begin building a comPrehensive database of SongFest song texts. SPecific rePertoire to be included will be chosen by Graham Johnson together with other faculty, and with regard to choices by the Performing fellows of SongFest 2008. All 2008 Performers’ names will be included in the Book . SongFest Book of Words devised by Graham Johnson Poet biograPhies by David TriPPett Programs researched and edited by John Steele Ritter SongFest 2008 Table of Contents Songfest 2008 Concerts . -

Publishing Swinburne; the Poet, His Publishers and Critics

UNIVERSITY OF READING Publishing Swinburne; the poet, his publishers and critics. Vol. 1: Text Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Language and Literature Clive Simmonds May 2013 1 Abstract This thesis examines the publishing history of Algernon Charles Swinburne during his lifetime (1837-1909). The first chapter presents a detailed narrative from his first book in 1860 to the mid 1870s: it includes the scandal of Poems and Ballads in 1866; his subsequent relations with the somewhat dubious John Camden Hotten; and then his search to find another publisher who was to be Andrew Chatto, with whom Swinburne published for the rest of his life. It is followed by a chapter which looks at the tidal wave of criticism generated by Poems and Ballads but which continued long after, and shows how Swinburne responded. The third and central chapter turns to consider the periodical press, important throughout his career not just for reviewing but also as a very significant medium for publishing poetry. Chapter 4 on marketing looks closely at the business of producing and of selling Swinburne’s output. Finally Chapter 5 deals with some aspects of his career after the move to Putney, and shows that while Theodore Watts, his friend and in effect his agent, was making conscious efforts to reshape the poet, some of Swinburne’s interests were moving with the tide of public taste; how this was demonstrated in particular by his volume of Selections and how his poetic oeuvre was finally consolidated in the Collected Edition at the end of his life. -

The Poets of Modern France

The ‘ P O E T S of M O D E R N F R A N C E by L U D W I G L E W I S O H N ‘ M . iI T . T D . A , pno m sson AT TH E OHIO STATE UN IVERSITY Y B HUEB S‘CH MCMXIX W. N EW O RK . C O P Y R I G HT , 1 9 1 8 . B Y W HUE B B . S C H Fir s t r in tin r il 1 9 1 8 p g, A p , n in r S ec o d pr tmg, Fe b r ua y , 1 9 19 D A P R N TE . S . I I N U . PREFACE IT e the which we is tim that art of translation , of h e e e e h av many b autiful xampl s in English , s ould b h e e strictly distinguished from t e trade . Lik the e acting or playing of music, it is an art of int r r etation e ffi e he h e e p , mor di cult than it r in t is r sp ct that you must interpret your original in a medium e e e e h . e e n v r cont mplat d by its aut or It r quir s , at e an e a n e h h its b st, x cti g and imaginativ sc olars ip, for you must understand your text in its fullest and most livin g sense ; it requires a power over the instrument of your own language no less com ’ l ete the e the e h p than virtuoso s ov r pianofort , t an ’ the actor s over the expression of his voice or the e e e g stur s of his body . -

Download File

Out of the Néant into the Everyday: A Rediscovery of Mallarmé’s Poetics Séverine C. Martin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Science COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Séverine C. Martin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Out of the Néant into the Everyday: A Rediscovery of Mallarmé’s Poetics Séverine C. Martin This dissertation, focusing on the Vers de circonstance, takes issue with traditional views on Stéphane Mallarmé’s aesthetics and his positioning on the relation of art to society. Whereas Mallarmé has often been branded as an ivory-tower poet, invested solely in abstract ideals and removed from the masses, my research demonstrates his interest in concrete essences and the small events of the everyday. As such, the Vers de circonstance offer an exemplary entry point to understanding these poetic preoccupations as the poems of this collection are both characterized by their materiality and their celebration of ordinary festivities. Indeed, most of the poems either accompany or are directly written on objects that were offered as gifts on such occasions as birthdays, anniversaries or seasonal holidays. The omnipresence of objects and dates that can be referred back to real events displays Mallarmé’s on-going questioning on the relation of art to reality. As I show, some of these interrogations rejoin the aesthetic preoccupations of the major artistic currents of the time, such as Impressionism in France and the Decorative Arts in England. These movements were defining new norms for the representation of reality in reaction to the changes of nineteenth century society. -

"Fiona Macleod". Vol

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

An Exploration of the Early Training and Song Juvenilia of Samuel Barber

THE FORMATIVE YEARS: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EARLY TRAINING AND SONG JUVENILIA OF SAMUEL BARBER Derek T. Chester, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2013 APPROVED: Jennifer Lane, Major Professor Stephen Dubberly, Committee Member Elvia Puccinelli, Committee Member Jeffrey Snider, Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Chester, Derek T. The Formative Years: An Exploration of the Early Training and Song Juvenilia of Samuel Barber. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2013, 112 pp., 32 musical examples, bibliography, 56 titles. In the art of song composition, American composer Samuel Barber was the perfect storm. Barber spent years studying under superb instruction and became adept as a pianist, singer, composer, and in literature and languages. The songs that Barber composed during those years of instruction, many of which have been posthumously published, are waypoints on his journey to compositional maturity. These early songs display his natural inclinations, his self-determination, his growth through trial and error, and the slow flowering of a musical vision, meticulously cultivated by the educational opportunities provided to him by his family and his many devoted mentors. Using existing well-known and recently uncovered biographical data, as well as both published and unpublished song juvenilia and mature songs, this dissertation examines the importance of Barber’s earliest musical and academic training in relationship to his development as a song composer. Copyright 2013 by Derek T. Chester ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I sang my first Samuel Barber song at the age of eighteen. -

William Sharp (Fiona Macleod)

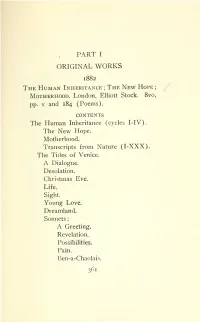

PART I ORIGINAL WORKS 1882 The Human Inheritance; The New Hope; Motherhood. London. Elliott Stock. 8vo, pp. v and 184 (Poems). CONTENTS The Human Inheritance (cycles 1-IV). The New Hope. Motherhood. Transcripts from Nature (I-XXX). The Tides of Venice. A Dialogue. Desolation. Christmas Eve. Life. Sight. Young Love. Dreamland. Sonnets : A Greeting. Revelation. Possibilities. Pain. Ben-a-Chaolais. 361 William Sharp Spring-wind. To the Spirit Called Laudanum. Lines. The Redeemer. Last Words. Pictorialism in Verse, issued in the Port- folio of Artistic Monographs (November, 1882). London. Seeley and Co. Dante Gabriel Rossetti : A Record and a Study. The Frontispiece is a reproduction of D. G. Rossetti's Etching of his Sonnet on a Sonnet. London. Macmillan & Co. 8vo, p. 432, appendix and Supplementary List to Chapter III. 1884 Earth's Voices: Transcripts from Nature: Sospitra and Other Poems. London. Elliot Stock. 8vo, pp. viii and 207. CONTENTS Earth's Voices : 1. Hymn of the Forests. 2. Hymn of Rivers. 3. The Song of Streams. 4. The Song of Waterfalls. 5. Song of the Deserts. 6. Song of the Cornfields. 7. Song of the Winds. 8. Song of Flowers. 9. The Wild Bee. 362 Bibliography 10. The Field Mouse. ii. The Song of the Lark. 12. The Song- of the Thrush. 13. The Song of the Nightingale. 14. The Rain Songs. 15. The Snow-Whispers. 16. Sigh of the Mists. 17. The Red Stag. 18. The Hymn of the Eagle. 19. The Cry of the Tiger. 20. The Chant of the Lion. 21. The Hymn of the Mountains. -

Julio Herrera Y Reissig Traductor

Julio Herrera y Reissig traductor Silvia Antúnez Rodríguez-Villamil (Universidad de la República) RESUMEN: Julio Herrera y ABSTRACT: Julio Herrera y Reissig, poeta modernista Reissig, the modernist poet from uruguayo, publica en 1903 Uruguay, published in 1903, in parte de sus traducciones de the magazine Almanaque REVISTA ÚRSULA Nº2 autores franceses en la revista artístico del siglo XX, part of his (2018) Almanaque artístico del siglo translations of the work of French XX. Diez años después se authors. Ten years later, post- darán a conocer, post-mortem, mortem, the rest of his sus demás traducciones. translations will be published. El siguiente trabajo analiza la This paper analyzes the reach of dimensión de Herrera en su Herrera as a translator from calidad de traductor del French, particularly his francés, en particular del translations of the French simbolista francés Albert symbolist Albert Samain. Those Samain. Dichas traducciones translations are tightly related to guardan un estrecho vínculo Herrera´s own work. con la obra del propio Herrera. PALABRAS CLAVE: KEY WORDS: translation, traducción, Modernismo, Modernism, symbolism, simbolismo, circulación, circulation, reception, poetry, recepción, conexión, connection, appropriation. apropiación. El uruguayo Julio Herrera y Reissig, integrante de la Generación del Novecientos, es uno de los mayores representantes del modernismo latinoamericano. Además de su actividad creadora, este poeta fundó dos revistas literarias: La Revista (trece números entre 1899 y 1900) y La Nueva Atlántida (1907). También publicó artículos y poemas en diarios y revistas de la época entre las que se destaca su colaboración en Almanaque artístico del siglo XX (1901-1903) en el que publica –nº 3, en 1903– traducciones de poemas de Albert Samain, Charles Baudelaire y de Émile Zola. -

Lyra Celtica : an Anthology of Representative Celtic Poetry

m^ 0^. 3)0T gaaggg^g'g'g^g'g'g^^^gg'^^^ gggjggggg^g^^gsgg^gggs ^^ oooooooo ^^ — THE COLLECTED WORKS OF "FIONA MACLEOD" (WILLIAM SHARP) I. Pharais ; The Mountain Lovers. II. The Sin-Eater ; The Washer of the Ford, Etc. III. The Dominion of Dreams ; Under the Dark Star. IV. The Divine Adventure ; lona ; Studies in Spiritual History. V. The Winged Destiny ; Studies in the Spiritual History of the Gael. VI. The Silence of Amor; Where the Forest Murmurs. VII. Poems and Dramas. The Immortal Hour In paper covers. SELECTED WRITINGS OF WILLIAM SHARP I. Poems. II. Studies and Appreciations. III. Papers, Critical and Reminiscent. IV. Literary, Geography, and Travel Sketches. V. Vistas : The Gipsy Christ and other Prose Imaginings. Uniform with above, in two volumes A MEMOIR OF WILLIAM SHARP (FIONA MACLEOD) Compiled by Mrs William Sharp LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN "The Celtic Library LYRA CELTICA First Edition ..... 1896 Second Edition (ReHsed and EnloTged) . 1924 LYRA CELTICA AN ANTHOLOGY OF REPRE- SENTATIVE CELTIC POETRY EDITED BY E. A. SHARP AND J. MATTHAY WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES By WILLIAM SHARP ANCIENT IRISH, ALBAN, GAELIC, BRETON, CYMRIC, AND MODERN SCOTTISH AND IRISH CELTIC POETRY EDINBURGH: JOHN GRANT 31 GEORGE IV. BRIDGE 1924 4 Ap^ :oT\^ PRINTED IN ORgAT BRITAIH BY OLIVER AND BOTD BDINBUROH CONTENTS a troubled EdeHy rich In throb of heart GEORGE MEREDITH CONTENTS PAGB INTRODUCTION .... xvii ANCIENT IRISH AND SCOTTISH The Mystery of Amergin The Song of Fionn .... Credhe's Lament .... Cuchullin in his Chariot . Deirdrc's Lament for the Sons of Usnach The Lament of Queen Maev The March of the Faerie Host . -

A History of French Literature from Chanson De Geste to Cinema

A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD HH A History of French Literature For Olive A History of French Literature From Chanson de geste to Cinema DAVID COWARD © 2002, 2004 by David Coward 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of David Coward to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2002 First published in paperback 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coward, David. A history of French literature / David Coward. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–631–16758–7 (hardback); ISBN 1–4051–1736–2 (paperback) 1. French literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PQ103.C67 2002 840.9—dc21 2001004353 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. 1 Set in 10/13 /2pt Meridian by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com Contents