Fiona Macleod: Poetic Genesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Songs of Michael Head: the Georgian Settings (And Song Catalogue)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 The onS gs of Michael Head: The Georgian Settings (And Song Catalogue). Loryn Elizabeth Frey Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Frey, Loryn Elizabeth, "The onS gs of Michael Head: The Georgian Settings (And Song Catalogue)." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4985. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4985 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Perfect Fool (1923)

The Perfect Fool (1923) Opera and Dramatic Oratorio on Lyrita An OPERA in ONE ACT For details visit https://www.wyastone.co.uk/all-labels/lyrita.html Libretto by the composer William Alwyn. Miss Julie SRCD 2218 Cast in order of appearance Granville Bantock. Omar Khayyám REAM 2128 The Wizard Richard Golding (bass) Lennox Berkeley. Nelson The Mother Pamela Bowden (contralto) SRCD 2392 Her son, The Fool speaking part Walter Plinge Geoffrey Bush. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime REAM 1131 Three girls: Alison Hargan (soprano) Gordon Crosse. Purgatory SRCD 313 Barbara Platt (soprano) Lesley Rooke (soprano) Eugene Goossens. The Apocalypse SRCD 371 The Princess Margaret Neville (soprano) Michael Hurd. The Aspern Papers & The Night of the Wedding The Troubadour John Mitchinson (tenor) The Traveller David Read (bass) SRCD 2350 A Peasant speaking part Ronald Harvi Walter Leigh. Jolly Roger or The Admiral’s Daughter REAM 2116 Narrator George Hagan Elizabeth Maconchy. Héloïse and Abelard REAM 1138 BBC Northern Singers (chorus-master, Stephen Wilkinson) Thea Musgrave. Mary, Queen of Scots SRCD 2369 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Leader, Reginald Stead) Conducted by Charles Groves Phyllis Tate. The Lodger REAM 2119 Produced by Lionel Salter Michael Tippett. The Midsummer Marriage SRCD 2217 A BBC studio recording, broadcast on 7 May 1967 Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir John in Love REAM 2122 Cover image : English: Salamander- Bestiary, Royal MS 1200-1210 REAM 1143 2 REAM 1143 11 drowned in a surge of trombones. (Only an ex-addict of Wagner's operas could have 1 The WIZARD is performing a magic rite 0.21 written quite such a devastating parody as this.) The orchestration is brilliant throughout, 2 WIZARD ‘Spirit of the Earth’ 4.08 and in this performance Charles Groves manages to convey my father's sense of humour Dance of the Spirits of the Earth with complete understanding and infectious enjoyment.” 3 WIZARD. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.Broken or indistinct phnt, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthonzed copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion Oversize materials (e g . maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMl® UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE MICHAEL HEAD’S LIGHT OPERA, KEY MONEY A MUSICAL DRAMATURGY A Document SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By MARILYN S. GOVICH Norman. Oklahoma 2002 UMl Number: 3070639 Copyright 2002 by Govlch, Marilyn S. All rights reserved. UMl UMl Microform 3070639 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17. United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

Poems of Ossian

0/», IZ*1. /S^, £be Canterbury fl>oets. Edited by William Sharp. POEMS OF OSSIAN. SQ OEMS OF CONTENTS. viii CONTENTS. PAGE Cathlin of Clutha: a Poem . .125 sub-malla of lumon : a poem . 135 The War of Inis-thona : a Poem 4.3 The Songs of Selma . 151 Fingal: an Ancient Epic Poem- I. Book . .163 Book II. 183 Book III. .197 Book IV. .... 213 Book V. 227 Book VI. ..... 241 Lathmon : a Poem .... 255 \Dar-Thula : a Poem . .271 The Death of Cuthullin : a Poem . 289 INTRODUCTION. ROM the earliest ages mankind have been lovers of song and tale. To their singers in times of old men looked for comfort in sorrow, for inspiration in battle, and for renown after death. Of these singers were the prophets of Israel, the poets and rhapsodes of ancient Greece, the skalds of the Scandinavian sea-kings, and the bards of the Celtic race. The office was always most honour- able, the bard coming next the hero in esteem ; and thus, first of the fine arts, was cultivated the art of song. Down to quite a recent time the household of no Highland chief was complete without its bard, to sing the great deeds of the race's ancestors. And to the present day, though the locomotive and the printing press have done much to kill these customs of a more heroic age, it is not difficult to find in the Highland glens those who can still recite a " tale of the times of old." x INTRODUCTION. During the troubles of the Reformation in the sixteenth century, of the Civil Wars .and Revolu- tion in the seventeenth, and of the Parliamentary Union and Jacobite Rebellions in the early part of the eighteenth, the mind of Scotland was entirely engrossed with politics, and the Highlands them- selves were continually unsettled. -

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him. -

Publishing Swinburne; the Poet, His Publishers and Critics

UNIVERSITY OF READING Publishing Swinburne; the poet, his publishers and critics. Vol. 1: Text Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Language and Literature Clive Simmonds May 2013 1 Abstract This thesis examines the publishing history of Algernon Charles Swinburne during his lifetime (1837-1909). The first chapter presents a detailed narrative from his first book in 1860 to the mid 1870s: it includes the scandal of Poems and Ballads in 1866; his subsequent relations with the somewhat dubious John Camden Hotten; and then his search to find another publisher who was to be Andrew Chatto, with whom Swinburne published for the rest of his life. It is followed by a chapter which looks at the tidal wave of criticism generated by Poems and Ballads but which continued long after, and shows how Swinburne responded. The third and central chapter turns to consider the periodical press, important throughout his career not just for reviewing but also as a very significant medium for publishing poetry. Chapter 4 on marketing looks closely at the business of producing and of selling Swinburne’s output. Finally Chapter 5 deals with some aspects of his career after the move to Putney, and shows that while Theodore Watts, his friend and in effect his agent, was making conscious efforts to reshape the poet, some of Swinburne’s interests were moving with the tide of public taste; how this was demonstrated in particular by his volume of Selections and how his poetic oeuvre was finally consolidated in the Collected Edition at the end of his life. -

KHCD-BOP2CD Track Listing - LP Set Notes Available As PDF - See Opera Page Disc 1

KHCD-BOP2CD Track Listing - LP Set Notes available as PDF - see Opera Page Disc 1 1. Gustav Holst: Sita (closing scene from Act III, edited by Colin Matthews) (22:49) Sita: Penelope Chalmers (soprano); Surpanakha: Jane Smith (alto); Ravana: Mark Hofman (baritone); The Earth: Carole Leatherby (contralto); Rama: Dafydd Wyn Phillips (baritone); Voices of the Earth (women's voices): the company 2. Hamish MacCunn: "Effie's Cradle Song" (Jeanie Deans) (3:49) - Jenny Miller (mezzo) 3. Edward W. Naylor: The Angelus (duet, Act II) (11:44) - Breatrice: Tommie Crowell Anderson (soprano); Francis: Kenneth Brown (tenor) 4. Ethyl Smyth: "Suppose you mean to do a given thing" and aria "What if I were young again" (The Boatswain's Mate) (8:34) - Tommie Crowell Anderson (soprano) 5. Baron Frederic d'Erlanger: "Angel Claire's Aria" (Tess) (5:07) - Kenneth Brown (tenor) 6. Frederick Corder: "Minna's Song" (Nordisa) (4:21) - Penelope Davis (soprano) Disc 2 1. Frederick Delius: Irmelin (closing scene) (13:32) - Irmelin: Janine Osborne (soprano); Nils: David Skewes (tenor) 2. Rutland Boughton: The Immortal Hour (closing scene) (16:47) - Etain: Jeanette Wilson (soprano); Midir: David Skewes (tenor); Eochaidh: Stuart Conroy (baritone); Faery chorus: the company 3. Sir Charles Villiers Stanford: Much Ado About Nothing (ensemble from Act I) (16:53) - Hero: Jeanette Wilson (soprano); Beatrice: Jenny Miller (mezzo-soprano); Benedict: Michael Riddiford (baritone); Don John: Nigel Fair (bass); Borachio: David Wilson (tenor); Claudio: Joh Hayward (tenor); Don Pedro: Dafydd Wyn Phillips (baritone); Lenato: John Milne (bass) 4. Arthur Goring Thomas: "All yet is tranquil" - "What would I do for my Queen" (Esmeralda) (6:22) - Mark Hoffman (baritone) 5. -

Rutland Boughton and the Glastonbury Festivals, by Michael Hurd (Review) Julian Onderdonk West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Music Theory, History & Composition College of Visual & Performing Arts 9-1995 Rutland Boughton and the Glastonbury Festivals, by Michael Hurd (review) Julian Onderdonk West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/musichtc_facpub Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Onderdonk, J. (1995). Rutland Boughton and the Glastonbury Festivals, by Michael Hurd (review). Notes, Second Series, 52(1), 108-109. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/musichtc_facpub/42 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Visual & Performing Arts at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Theory, History & Composition by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 108 NOTES, September 1995 genre, the carnival samba and the ball- cycle that took thirty-seven years to com- room samba of the 1920s and 1930s. (P. plete. Sixty-two music examples accompany 155) the text, while a discography and appen- dixes listing his compositions and literary When discussing the relationship of writings follow. Villa-Lobos's individual style to the various That there is yet another appendix, one musics that have appeared under the label giving the cast listings for the principal pro- of nationalism Behague writes: "The de- ductions of the Glastonbury Festival (1914- termination of the meanings of musical na- 26), is a reminder of what the book's title tionalism warrants, therefore, more reflec- already asserts. This is a critical biography tion, to which the present study attempts that places special emphasis on Boughton's to contribute, for all of these ideas have work as that Festival's founder and spiritual relevant applications to the case of Brazil- father. -

"Fiona Macleod". Vol

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

Professor Jeremy Summerly 17 September 2020

RADIO IN THE 78 RPM ERA (1920-1948) PROFESSOR JEREMY SUMMERLY 17 SEPTEMBER 2020 At 7.10 pm on 15 June 1920, a half-hour broadcast was given by Australian prima donna Dame Nellie Melba (‘the world’s very best artist’). Singing from a workshop at the back of the Marconi Wireless and Telegraph Company, the 59-year old soprano described her Chelmsford recital as ‘the most wonderful experience of my career’. The transmission was received all around Europe, as well as in Soltan-Abad in Persia (now Arak in Iran) to the East, and Newfoundland (at the time a Dominion of the British Empire) to the West. Dame Nellie’s recital became recognized as Britain’s first official radio broadcast and the Daily Mail (predictably, perhaps, in its role as sponsor) described the event as ‘a great initiation ceremony; the era of public entertainment may be said to have completed its preliminary trials’. The Radio Corporation of America had been founded a year earlier, run by a young Russian- American businessman David Sarnoff. Sarnoff believed that ‘broadcasting represents a job of entertaining, informing and educating the nation, and should therefore be distinctly regarded as a public service’, words that were later echoed more famously by John Reith of the British Broadcasting Company. On 11 May 1922, daily radio transmissions of an hour began from the 7th floor of Marconi House at London’s Aldwych. The Marconi Company’s London station was known as 2LO and its first concert (for voice, cello, and piano) was broadcast on 24 June; the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) broadcast from Marconi House on 7 October. -

An Exploration of the Early Training and Song Juvenilia of Samuel Barber

THE FORMATIVE YEARS: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EARLY TRAINING AND SONG JUVENILIA OF SAMUEL BARBER Derek T. Chester, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2013 APPROVED: Jennifer Lane, Major Professor Stephen Dubberly, Committee Member Elvia Puccinelli, Committee Member Jeffrey Snider, Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Chester, Derek T. The Formative Years: An Exploration of the Early Training and Song Juvenilia of Samuel Barber. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2013, 112 pp., 32 musical examples, bibliography, 56 titles. In the art of song composition, American composer Samuel Barber was the perfect storm. Barber spent years studying under superb instruction and became adept as a pianist, singer, composer, and in literature and languages. The songs that Barber composed during those years of instruction, many of which have been posthumously published, are waypoints on his journey to compositional maturity. These early songs display his natural inclinations, his self-determination, his growth through trial and error, and the slow flowering of a musical vision, meticulously cultivated by the educational opportunities provided to him by his family and his many devoted mentors. Using existing well-known and recently uncovered biographical data, as well as both published and unpublished song juvenilia and mature songs, this dissertation examines the importance of Barber’s earliest musical and academic training in relationship to his development as a song composer. Copyright 2013 by Derek T. Chester ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I sang my first Samuel Barber song at the age of eighteen. -

William Sharp (Fiona Macleod)

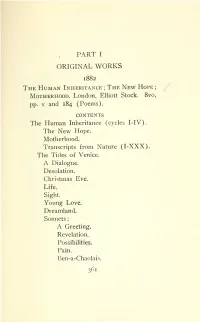

PART I ORIGINAL WORKS 1882 The Human Inheritance; The New Hope; Motherhood. London. Elliott Stock. 8vo, pp. v and 184 (Poems). CONTENTS The Human Inheritance (cycles 1-IV). The New Hope. Motherhood. Transcripts from Nature (I-XXX). The Tides of Venice. A Dialogue. Desolation. Christmas Eve. Life. Sight. Young Love. Dreamland. Sonnets : A Greeting. Revelation. Possibilities. Pain. Ben-a-Chaolais. 361 William Sharp Spring-wind. To the Spirit Called Laudanum. Lines. The Redeemer. Last Words. Pictorialism in Verse, issued in the Port- folio of Artistic Monographs (November, 1882). London. Seeley and Co. Dante Gabriel Rossetti : A Record and a Study. The Frontispiece is a reproduction of D. G. Rossetti's Etching of his Sonnet on a Sonnet. London. Macmillan & Co. 8vo, p. 432, appendix and Supplementary List to Chapter III. 1884 Earth's Voices: Transcripts from Nature: Sospitra and Other Poems. London. Elliot Stock. 8vo, pp. viii and 207. CONTENTS Earth's Voices : 1. Hymn of the Forests. 2. Hymn of Rivers. 3. The Song of Streams. 4. The Song of Waterfalls. 5. Song of the Deserts. 6. Song of the Cornfields. 7. Song of the Winds. 8. Song of Flowers. 9. The Wild Bee. 362 Bibliography 10. The Field Mouse. ii. The Song of the Lark. 12. The Song- of the Thrush. 13. The Song of the Nightingale. 14. The Rain Songs. 15. The Snow-Whispers. 16. Sigh of the Mists. 17. The Red Stag. 18. The Hymn of the Eagle. 19. The Cry of the Tiger. 20. The Chant of the Lion. 21. The Hymn of the Mountains.