Qohelet's Cultural Dialectics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pleasing and the Awesome: on the Beauty of Humans in the Old Testament

652 Loader, “The Pleasing and the Awesome,” OTE 24/3 (2011): 652-667 The Pleasing and the Awesome: On the Beauty of Humans in the Old Testament JAMES ALFRED LOADER (UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA AND UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA) ABSTRACT Profiting from the OT research programme held at the University of South Africa during August 2010, this paper further investigates dif- ferent aspects of the concept of beauty in the Old Testament (OT). The use of the concept of human beauty and the beauty of human achievement is investigated in a broad variety of text types. Repre- sentative texts are examined where the concept occurs as a literary motif. It is found that human beauty, both erotic and non-erotic, as well as the metaphorical use of the concept are intertwined with de- scriptions of awe not only in the terminology, but also in the actual use to which it is put in texts from practically all genres. It is con- cluded that a coherent aesthetic is found in OT texts from different periods, which remains stable despite diverging historical and theo- logical contexts. The contours emerging from the texts seem to square with the Kantian concept of the beautiful and Goethe’s view of the awesome. A INTRODUCTION In August 2010 I delivered a paper on a facet of my exploration of the concept of beauty in the OT.1 The lively discussion prompted the idea that not only a basic survey,2 but several papers are called for in which the topic is examined from various angles each in its own right. -

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death Remi Jedwab and Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama⇤ April 16, 2018 Abstract We study the Black Death pogroms to shed light on the factors determining when a minority group will face persecution. In theory, negative shocks increase the likelihood that minorities are persecuted. But, as shocks become more severe, the persecution probability decreases if there are economic complementarities between majority and minority groups. The effects of shocks on persecutions are thus ambiguous. We compile city-level data on Black Death mortality and Jewish persecutions. At an aggregate level, scapegoating increases the probability of a persecution. However, cities which experienced higher plague mortality rates were less likely to persecute. Furthermore, for a given mortality shock, persecutions were less likely in cities where Jews played an important economic role and more likely in cities where people were more inclined to believe conspiracy theories that blamed the Jews for the plague. Our results have contemporary relevance given interest in the impact of economic, environmental and epidemiological shocks on conflict. JEL Codes: D74; J15; D84; N33; N43; O1; R1 Keywords: Economics of Mass Killings; Inter-Group Conflict; Minorities; Persecutions; Scapegoating; Biases; Conspiracy Theories; Complementarities; Pandemics; Cities ⇤Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, George Washington University, [email protected]. Mark Koyama: Associate -

JOURNAL of THEOLOGY 42- 14.2 Fall

MJT for the Church Preachers and Preaching, II Preachers and Preaching, II and Preaching, Preachers MIDWESTERN JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY 14.2 - Fall 2015 MIDWESTERN BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY Fall 2015 Vol. 14 No.2 MIDWESTERN JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY EDITORIAL BOARD ISBN: 1543-6977 Jason K. Allen, Executive Editor Jason G. Duesing, Academic Editor Michael D. McMullen, Managing Editor N. Blake Hearson, Book Review Editor Th e Midwestern Journal of Th eology is published biannually by Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary, Kansas City, MO, 64118, and by Th e Covington Group, Kansas City, MO. Information about the journal is available at the seminary website: www.mbts.edu. Th e Midwestern Journal of Th eology is indexed in the Southern Baptist Periodical Index and in the Christian Periodical Index. Address all editorial correspondence to: Editor, Midwestern Journal of Th eology, 5001 N. Oak Traffi cway, Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary, Kansas City, Mo, 64118. Address books, software, and other media for review to: Book Review Editor, Midwestern Journal of Th eology, 5001 N. Oak Traffi cway, Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary, Kansas City, Mo, 64118. All submissions should follow the SBL Handbook of Style in order to be considered for publication. Th e views expressed in the following articles and reviews are not necessarily those of the faculty, the administration, or the trustees of the Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary. © Copyright 2015 All rights reserved by Midwestern Baptist Th eological Seminary MJT Fall 2015 Cover v6.indd 2 11/11/15 8:48 AM MIDWESTERN JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY FALL 2015 (Vol. 14/ No. -

University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007 Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. THE BOOK OF JUBILEES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FROM THE FIRST GERMAN TRANSLATION OF 1850 TO THE ENOCH SEMINAR OF 2007 ISAAC W. OLIVER , University of Michigan VERONIKA BACHMANN , University of Zurich The following annotated bibliography provides summaries of the most influential scholarly works dedicated to the Book of Jubilees written between 1850 and 2006. * The year 1850 opens the period of modern research on Jubilees thanks to Dillmann’s translation of the Ethiopic text of Jubilees into German; the Enoch Seminar of 2007 represents the largest gathering of international scholars on the document in modern times. -

Founders Journal from Founders Ministries | Winter/Spring 1995 | Issue 19/20

FOUNDERS JOURNAL FROM FOUNDERS MINISTRIES | WINTER/SPRING 1995 | ISSUE 19/20 SOUTHERN BAPTISTS AT THE CROSSROADS Southern Baptists at the Crossroads Returning to the Old Paths Special SBC Sesquicentennial Issue, 1845-1995 Issue 19/20 Winter/Spring 1995 Contents [Inside Cover] Southern Baptists at the Crossroads: Returning to the Old Paths Thomas Ascol The Rise & Demise of Calvinism Among Southern Baptists Tom Nettles Southern Baptist Theology–Whence and Whither? Timothy George John Dagg: First Writing Southern Baptist Theologian Mark Dever To Train the Minister Whom God Has Called: James Petigru Boyce and Southern Baptist Theological Education R. Albert Mohler, Jr. What Should We Think Of Evangelism and Calvinism? Ernest Reisinger Book Reviews By His Grace and for His Glory, by Tom Nettles, Baker Book House, 1986, 442 pages, $13.95. Reviewed by Bill Ascol Abstract of Systematic Theology, by James Petigru Boyce. Originally published in 1887; reprinted by the den Dulk Christian Foundation, P. O. Box 1676, Escondido, CA 92025; 493 pages, $15.00. Reviewed by Fred Malone The Forgotten Spurgeon, by Iain Murray , Banner of Truth, 1966, 254 pp, $8.95. Reviewed by Joe Nesom Contributors: Dr. Thomas K. Ascol is Pastor of the Grace Baptist Church in Cape Coral, Florida. Mr. Bill Ascol is Pastor of the Heritage Baptist Church in Shreveport, Louisiana. Dr. Mark Dever is Pastor of the Capitol Hill Metropolitan Baptist Church in Washington, DC. Dr. Timothy George is Dean of the Beeson Divinity School in Birmingham, Alabama. Dr. Fred Malone is Pastor of the First Baptist Church in Clinton, Louisiana. Dr. R. Albert Mohler is President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. -

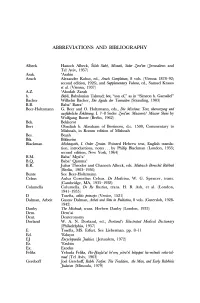

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Curriculum Vitae

CHRISTIAN WILDBERG Department of Classics | Program in Classical Philosophy Princeton University | 147 East Pyne | Princeton, NJ 08544 (609) 258 3958 (office) | (609) 258 1943 (fax) [email protected] _______________________________________________________________________ Curriculum vitae SPECIAL INTERESTS History of Western Philosophy from the Beginning to Late Antiquity; Neoplatonism; Early Christian Philosophy; Ancient Science; Ancient Greek Religion; Tragedy; Moral Philosophy (Problem of Evil) EDUCATION University of Cambridge, England, 1979–84 1984 Ph.D. (Cantab.) in Classics. Dissertation entitled: John Philoponus’ Criticism of Aristotle’s Theory of Ether. 2 Vols. Dissertation advisors: G.E.L. Owen and G.E.R. Lloyd; examiners: David Sedley and Richard Sorabji. Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany, 1976–79 and 1984–85 1985 Mag.Theol. (Marburg). Masters thesis entitled: Ursprung, Inhalt und Funktion der Weisheit bei Jesus Sirach und in den Sentenzen des Menander. Thesis advisor: Otto Kaiser. PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT Professor of Classics, Princeton University, 2003–present Director of the Seeger Program for Hellenic Studies, 2011–present Master of Forbes College, Princeton University, 2006–2010 Associate Professor of Classics, Princeton University, 1996–2003 Junior Fellow, Center for Hellenic Studies, Washington, 1995–96 Assistant Professor, Seminar für Klassische Philologie, Freie Universität Berlin, 1988–94 Visiting Lecturer, Dept of Classics & Dept of Philosophy, University of Texas at Austin, 1987–88 Research Fellow, Gonville -

Reasonable Man’

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2019 The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ Johnny Sakr The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Law Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Sakr, J. (2019). The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ (Master of Philosophy (School of Law)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/215 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Conjecture from the Universality of Objectivity in Jurisprudential Thought: The Universal Presence of a ‘Reasonable Man’ By Johnny Michael Sakr Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Notre Dame Australia School of Law February 2019 SYNOPSIS This thesis proposes that all legal systems use objective standards as an integral part of their conceptual foundation. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will show that Jewish law, ancient Athenian law, Roman law and canon law use an objective standard like English common law’s ‘reasonable person’ to judge human behaviour. -

Jewish and Christian Perspectives on ??????? in Genesis 20:13 in the Ancient, Mediaeval and Reformed Exegesis

MAJT 28 (2017): 135-147 IN הִתְעּו JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN PERSPECTIVES ON GENESIS 20:13 IN THE ANCIENT, MEDIAEVAL AND REFORMATION EXEGESIS by Matthew Oseka Introduction acted as the subject in Genesis אלהים for which ,(הִתְעּו) THE PLURAL FORM of the verb 20:13, was often brought up for discussion in the history of biblical exegesis. Modern commentaries1 tend to explain this intriguing form as Abraham’s accommodation to Abimelech’s polytheistic background, namely, as a rhetorical concession made by Abraham to Abimelech. Indeed, it is arguable that within the parameters of the narrative Abraham tried to appease Abimelech and therefore adopted the phrasing which was common and absolutely inconspicuous. From a historical perspective, the plural forms concerning the Divine (e.g. Gen. 1:26; 11:7; 20:13) acted as focal points for exegetical and theological discussions in Jewish and Christian traditions. Granted that the literature on the origin of the Jewish2 1. As typified by: August Dillmann, Genesis Critically and Exegetically Expounded, vol. 2, trans. William Black Stevenson (Edinburgh: Clark, 1897), 122 [Genesis 20:13]; Samuel Rolles Driver, The Book of Genesis with Introduction and Notes (London: Methuen, 1904), 208 [Genesis 20:13]; Carl Friedrich Keil, Biblischer Kommentar über die Bücher Mose’s, vol. 1 (Leipzig: Dörffling and Franke, 1878), 204 [Genesis 20:13]; Andrew J. Schmutzer, “Did the ”,in Genesis 20:13 התעו אתי אלהים Gods Cause Abraham’s Wandering? An Examination of Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 35/2 (2010); Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis: 16-50, WBC (Dallas: Word, 1998), 73 [Genesis 20:13]. -

Manasseh in Scripture and Tradition: an Analysis of Ancient Sources and the Development of the Manasseh Tradition Steven A

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Seminary Masters Theses Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2002 Manasseh in Scripture and Tradition: An Analysis of Ancient Sources and the Development of the Manasseh Tradition Steven A. Graham This research is a product of the Master of Arts in Theological Studies (MATS) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Graham, Steven A., "Manasseh in Scripture and Tradition: An Analysis of Ancient Sources and the Development of the Manasseh Tradition" (2002). Seminary Masters Theses. 38. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/seminary_masters/38 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seminary Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY MANASSEH IN SCRIPTURE AND TRADITION: AN ANALYSIS OF ANCIENT SOURCES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MANASSEH TRADITION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE DEPARTMENT OF MINISTRY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEOLOGICAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY BY STEVEN A. GRAHAM PORTLAND, OREGON MAY2002 PORTLAND CENTER LIBRARY GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY PORTLAND, OR. 97223 o,~w;, nnn i1ttll1J 1ww',;:, ',.!1 ;,~;:,n:::1 1m',, w,,,', ,:::1',-n~ ,nm1 1:::1 n1Jl1', 01~i1 ,J:::l', o,;,',~ 1m .!11 rJlJ ~1i1 I have given my heart to search and to seek by wisdom concerning all that has been done under heaven. It is a task of distress that God has given to the children of men to be afflicted with. -

The Influence and Use of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2011 The Influence and Use of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels Reimar Vetne Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vetne, Reimar, "The Influence and Use of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels" (2011). Dissertations. 160. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE INFLUENCE AND USE OF DANIEL IN THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS by Reimar Vetne Adviser: Jon Paulien ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE INFLUENCE AND USE OF DANIEL IN THE SYNOPTIC GOSPELS Name of researcher: Reimar Vetne Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jon Paulien, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2011 Scholars have always been aware of influence from the book of Daniel in the Synoptic Gospels. Various allusions to Daniel have been discussed in numerous articles, monographs and commentaries. Now we have for the first time a comprehensive look at all the possible allusions to Daniel in one study. -

The Making of the Encyclopaedia Judaica and the Jewish Encyclopedia

THE MAKING OF THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA AND THE JEWISH ENCYCLOPEDIA David B. Levy, Ph. D., M.L.S. Description: The Jewish Encyclopedia and Encyclopaedia Judaica form a key place in most collections of Judaica. Both works state that they were brought into being to combat anti-Semitism. This presentation treats the reception history of both the JE and EJ by looking at the comments of their admirers and critics. It also assesses how both encyclopedias mark the application of social sciences and emphasis on Jewish history, as well as anthropology, archeology, and statistics. We will consider the differences between the JE and EJ, some of the controversies surrounding the making of the encyclopedias, and the particular political, ideological, and cultural perspectives of their contributing scholars. Introduction: David B. Levy (M.A., ’92; M.L.S., ’94; Ph. D., 2002) received a Ph. D. in Jewish studies with concentrations in Jewish philosophy, biblical The 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia and archeology, and rabbinics on May 23, 2002, from the 1972 Encyclopaedia Judaica form an Baltimore Hebrew University. David has worked in important place in collections of Judaica. the Humanities Department of the Enoch Pratt Public Library since 1994. He authored the Enoch Both works were brought into being to Pratt Library Humanities annotated subject guide combat anti-Semitism, to enlighten the web pages in philosophy (24 categories), ancient and public of new discoveries, and to modern languages (Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, German), and religion. He is widely disseminate Jewish scholarship. Both published. encyclopedias seek to counter-act the lack of knowledge of their generations and wide spread assimilation.