Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Space Vector Modulated Hybrid Series Active Filter for Harmonic Compensation

space vector modulated Hybrid Series Active Filter for Harmonic Compensation Sushree Diptimayee Swain∗, Pravat Kumar Ray† and Kanungo Barada Mohanty‡ Department of Electrical Engineering National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, Rourkela-769 008, India ∗[email protected] †[email protected] ‡[email protected] Abstract—This paper deals with the implementation of Hy- nomenon between the PPFs and source impedance. But the brid Series Active Power Filter (HSAPF) for compensation of usage of only APFs is a very costly solution because it needs harmonic voltage and current using Space Vector Pulse Width comparatively very large power converter ratings. Considering Modulation (SVPWM) technique. The Hybrid control approach based Synchronous Reference Frame(SRF) method is used to the merits of PPFs and APFs, Hybrid Active Power Filters are generate the appropriate reference voltages for HSAPF to com- designed HAPFs [9], [10] are very much efficient for reactive pensate reactive power. This HSAPF uses PI control to the outer power and harmonic compensation. The design of HAPFs are DC-link voltage control loop and SVPWM to the inner voltage based on cutting-edge power electronics technology, which control loop. The switching pattern for the switching of the includes power conversion circuits, semiconductor devices, inverter of series active power filter in HSAPF is generated using SVPWM technique. The proposed HSAPF is verified through analog/digital signal processing, voltage/current sensors and MATLAB Simulink version R2010 for SRF control -

52183 FRMS Cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1

4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1 Autumn 2012 No. 157 £1.75 Bulletin 4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:21 Page 2 NEW RELEASES THE ROMANTIC VIOLIN STEPHEN HOUGH’S CONCERTO – 13 French Album Robert Schumann A master pianist demonstrates his Hyperion’s Romantic Violin Concerto series manifold talents in this delicious continues its examination of the hidden gems selection of French music. Works by of the nineteenth century. Schumann’s late works Poulenc, Fauré, Debussy and Ravel rub for violin and orchestra had a difficult genesis shoulders with lesser-known gems by but are shown as entirely worthy of repertoire their contemporaries. status in these magnificent performances by STEPHEN HOUGH piano Anthony Marwood. ANTHONY MARWOOD violin CDA67890 BBC SCOTTISH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CDA67847 DOUGLAS BOYD conductor MUSIC & POETRY FROM THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE Conductus – 1 LOUIS SPOHR & GEORGE ONSLOW Expressive and beautiful thirteenth-century vocal music which represents the first Piano Sonatas experiments towards polyphony, performed according to the latest research by acknowledged This recording contains all the major works for masters of the repertoire. the piano by two composers who were born within JOHN POTTER tenor months of each other and celebrated in their day CHRISTOPHER O’GORMAN tenor but heard very little now. The music is brought to ROGERS COVEY-CRUMP tenor modern ears by Howard Shelley, whose playing is the paradigm of the Classical-Romantic style. HOWARD SHELLEY piano CDA67947 CDA67949 JOHANNES BRAHMS The Complete Songs – 4 OTTORINO RESPIGHI Graham Johnson is both mastermind and Violin Sonatas pianist in this series of Brahms’s complete A popular orchestral composer is seen in a more songs. -

Mark Hilliard Wilson St

X ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL X SEATTLE X 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 X 6:30 PM X MUSICAL PRAYER mark hilliard wilson St. James Cathedral Guitarist “Méditation” from Thaïs Jules Massenet 1842–1912 Etude No. 10 from 12 Etudes, Op. 6 Fernando Sor c. 1778–1839 Ave Maria Franz Schubert 1797–1828 Simple Gifts Joseph Brackett 1797–1882 Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Johann Sebastian Bach 1685–1750 Gymnopédie No. 1 from Trois Gymnopédies Erik Satie 1866–1925 Nigbati Iya Mi Ba Reriin Taiwo Adegoke “When my mother laughs” birth year unknown Theme from second movement ofNew World Symphony Antonín Dvořák 1841–1904 Prelude No. 1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier, BWV 846 J. S. Bach Woven World Andrew York b. 1958 Classical guitarist Mark Hilliard Wilson curates programs that explore the experiences of the heart through the ages, hoping to share some insight and reflection on our common humanity. He brings joy and technical finesse to the listener while integrating music from diverse backgrounds and different ages with a compelling story and a wry sense of humor. Performing regularly at festivals and concert series, Wilson has distinguished himself as a unique voice with programs that feature his own transcriptions of both the well-known and the obscure. Wilson’s compositions for the guitar have been appearing on stages throughout the Northwest US and Canada for over 15 years. He works in is the relatively unexplored genre of an ensemble of multiple guitars as the conductor, composer, arranger, and music director to the Guitar Orchestra of Seattle. Wilson has taught at Whatcom Community College and Bellevue College. -

Soundboardindexnames.Txt

SoundboardIndexNames.txt Soundboard Index - List of names 03-20-2018 15:59:13 Version v3.0.45 Provided by Jan de Kloe - For details see www.dekloe.be Occurrences Name 3 A & R (pub) 3 A-R Editions (pub) 2 A.B.C. TV 1 A.G.I.F.C. 3 Aamer, Meysam 7 Aandahl, Vaughan 2 Aarestrup, Emil 2 Aaron Shearer Foundation 1 Aaron, Bernard A. 2 Aaron, Wylie 1 Abaca String Band 1 Abadía, Conchita 1 Abarca Sanchis, Juan 2 Abarca, Atilio 1 Abarca, Fernando 1 Abat, Joan 1 Abate, Sylvie 1 ABBA 1 Abbado, Claudio 1 Abbado, Marcello 3 Abbatessa, Giovanni Battista 1 Abbey Gate College (edu) 1 Abbey, Henry 2 Abbonizio, Isabella 1 Abbott & Costello 1 Abbott, Katy 5 ABC (mag) 1 Abd ar-Rahman II 3 Abdalla, Thiago 5 Abdihodzic, Armin 1 Abdu-r-rahman 1 Abdul Al-Khabyyr, Sayyd 1 Abdula, Konstantin 3 Abe, Yasuo 2 Abe, Yasushi 1 Abel, Carl Friedrich 1 Abelard 1 Abelardo, Nicanor 1 Aber, A. L. 4 Abercrombie, John 1 Aberle, Dennis 1 Abernathy, Mark 1 Abisheganaden, Alex 11 Abiton, Gérard 1 Åbjörnsson, Johan 1 Abken, Peter 1 Ablan, Matthew 1 Ablan, Rosilia 1 Ablinger, Peter 44 Ablóniz, Miguel 1 Abondance, Florence & Pierre 2 Abondance, Pierre 1 Abraham Goodman Auditorium 7 Abraham Goodman House 1 Abraham, Daniel 1 Abraham, Jim 1 Abrahamsen, Hans Page 1 SoundboardIndexNames.txt 1 Abrams (pub) 1 Abrams, M. H. 1 Abrams, Richard 1 Abrams, Roy 2 Abramson, Robert 3 Abreu 19 Abreu brothers 3 Abreu, Antonio 3 Abreu, Eduardo 1 Abreu, Gabriel 1 Abreu, J. -

Download Download

МUSIC SUMMER FESTIVALS AS PROMOTERS OF THE SPA CULTURAL TOURISM: FESTIVAL OF CLASSICAL MUSIC VRNJCI Smiljka Isaković1, Jelena Borović-Dimić2 Abstract This paper is dedicated to the music summer festivals, a hallmark of the local community and the holder of the economic development of the region and the society, from ancient times to the present day. Special emphasis is placed on the International Festival of classical music "Vrnjci", held in Belimarković mansion in July, organized by the Homeland Мuseum – Castle of Culture of Vrnjaĉka Banja. A dramatic development of high technologies brought forth a new era based on conceptual creativity. Leisure time is prolonged, while tourism as one of the activities of spending leisure time is changing from passive to active. The cultural sector is becoming an important partner in the economic development of countries and cultural tourism is gaining in importance. Festival tourism in this country must be supported by the wider community and the state because the quality of cultural events makes us an equal competitor on the global tourism market. Keywords: cultural tourism, festivals, art, music, local self governments. Cultural Tourism The middle of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries can be called the period of tourism, since Stendhal popularized this term in France with his book "Memoirs of a tourist" (1838) and Englishman Thomas Cook opened his travel agency in 1841. Modern tourism experienced its first expansion between 1850 and 1870, enabled by the major railways networking in Europe -

Musical Acoustics - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 11/07/13 17:28 Musical Acoustics from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Musical acoustics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 11/07/13 17:28 Musical acoustics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Musical acoustics or music acoustics is the branch of acoustics concerned with researching and describing the physics of music – how sounds employed as music work. Examples of areas of study are the function of musical instruments, the human voice (the physics of speech and singing), computer analysis of melody, and in the clinical use of music in music therapy. Contents 1 Methods and fields of study 2 Physical aspects 3 Subjective aspects 4 Pitch ranges of musical instruments 5 Harmonics, partials, and overtones 6 Harmonics and non-linearities 7 Harmony 8 Scales 9 See also 10 External links Methods and fields of study Frequency range of music Frequency analysis Computer analysis of musical structure Synthesis of musical sounds Music cognition, based on physics (also known as psychoacoustics) Physical aspects Whenever two different pitches are played at the same time, their sound waves interact with each other – the highs and lows in the air pressure reinforce each other to produce a different sound wave. As a result, any given sound wave which is more complicated than a sine wave can be modelled by many different sine waves of the appropriate frequencies and amplitudes (a frequency spectrum). In humans the hearing apparatus (composed of the ears and brain) can usually isolate these tones and hear them distinctly. When two or more tones are played at once, a variation of air pressure at the ear "contains" the pitches of each, and the ear and/or brain isolate and decode them into distinct tones. -

Inhalt / Contents

Inhalt / Contents Grußwort / Greeting........................................... 7 II - Psalmvertonungen und Gebete / Vorwort / Preface................................................ 9 Psalm Settings and Prayers.............. 49 Ganz Europa im Fokus • Die Auswahl als repräsentativer Zeitspiegel und abgestimmt auf die heutige Praxis • Dominus regit m e.................................................. 50 Zur Gliederung der Chorstücke - Ein reichhaltiges Chorreper Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) toire • A cappella oder mit Begleitung? • Zur Interpretation - W ie der Hirsch schreiet / As the Hart Panteth.......... 58 Geistliche Chormusik im „langen 19. Jahrhundert" • Zur Heinrich Bellermann (1832-1903) Verwendung des Romantik-Begriffs im Titel des Chorbuchs • Editorische Anmerkungen - Zu den verwendeten Bibel Sicut cervus........................................................... 64 versionen • Hilfestellungen für die Probenarbeit Charles Gounod (1818-1893) All of Europe in the limelight • The selection as a represen Kot po mrzli studencini / As the Thirsting Hart Pants.. 67 tative reflection of the times, yet in tune with modern Hugolin Sattner (1851-1934) practice - The organisation of the choral pieces • A rich Sende dein Licht (Kanon) / and extensive choral repertoire • A cappella or with accom Send Out Thy Light (Canon)............................... 68 paniment? • Concerning performance • Sacred choral music Friedrich Schneider (1786-1853) in the "long nineteenth century" • On the use of the term "Romantik" in the title of this choir -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Mto.95.1.4.Cuciurean

Volume 1, Number 4, July 1995 Copyright © 1995 Society for Music Theory John D. Cuciurean KEYWORDS: scale, interval, equal temperament, mean-tone temperament, Pythagorean tuning, group theory, diatonic scale, music cognition ABSTRACT: In Mathematical Models of Musical Scales, Mark Lindley and Ronald Turner-Smith attempt to model scales by rejecting traditional Pythagorean ideas and applying modern algebraic techniques of group theory. In a recent MTO collaboration, the same authors summarize their work with less emphasis on the mathematical apparatus. This review complements that article, discussing sections of the book the article ignores and examining unique aspects of their models. [1] From the earliest known music-theoretical writings of the ancient Greeks, mathematics has played a crucial role in the development of our understanding of the mechanics of music. Mathematics not only proves useful as a tool for defining the physical characteristics of sound, but abstractly underlies many of the current methods of analysis. Following Pythagorean models, theorists from the middle ages to the present day who are concerned with intonation and tuning use proportions and ratios as the primary language in their music-theoretic discourse. However, few theorists in dealing with scales have incorporated abstract algebraic concepts in as systematic a manner as the recent collaboration between music scholar Mark Lindley and mathematician Ronald Turner-Smith.(1) In their new treatise, Mathematical Models of Musical Scales: A New Approach, the authors “reject the ancient Pythagorean idea that music somehow &lsquois’ number, and . show how to design mathematical models for musical scales and systems according to some more modern principles” (7). -

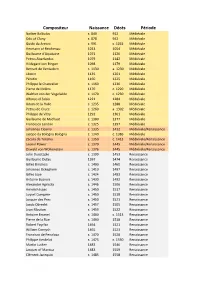

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

The Ten Violin Concertos of Charles-Auguste De Beriot: a Pedagogical Study

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 The eT n Violin Concertos of Charles-Auguste De Beriot: A Pedagogical Study. Nicole De carteret Hammill Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Hammill, Nicole De carteret, "The eT n Violin Concertos of Charles-Auguste De Beriot: A Pedagogical Study." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5694. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5694 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.