A Historical and Critical Analysis of 36 Valses Di Difficolta Progressiva, Op

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

52183 FRMS Cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1

4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1 Autumn 2012 No. 157 £1.75 Bulletin 4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:21 Page 2 NEW RELEASES THE ROMANTIC VIOLIN STEPHEN HOUGH’S CONCERTO – 13 French Album Robert Schumann A master pianist demonstrates his Hyperion’s Romantic Violin Concerto series manifold talents in this delicious continues its examination of the hidden gems selection of French music. Works by of the nineteenth century. Schumann’s late works Poulenc, Fauré, Debussy and Ravel rub for violin and orchestra had a difficult genesis shoulders with lesser-known gems by but are shown as entirely worthy of repertoire their contemporaries. status in these magnificent performances by STEPHEN HOUGH piano Anthony Marwood. ANTHONY MARWOOD violin CDA67890 BBC SCOTTISH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CDA67847 DOUGLAS BOYD conductor MUSIC & POETRY FROM THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE Conductus – 1 LOUIS SPOHR & GEORGE ONSLOW Expressive and beautiful thirteenth-century vocal music which represents the first Piano Sonatas experiments towards polyphony, performed according to the latest research by acknowledged This recording contains all the major works for masters of the repertoire. the piano by two composers who were born within JOHN POTTER tenor months of each other and celebrated in their day CHRISTOPHER O’GORMAN tenor but heard very little now. The music is brought to ROGERS COVEY-CRUMP tenor modern ears by Howard Shelley, whose playing is the paradigm of the Classical-Romantic style. HOWARD SHELLEY piano CDA67947 CDA67949 JOHANNES BRAHMS The Complete Songs – 4 OTTORINO RESPIGHI Graham Johnson is both mastermind and Violin Sonatas pianist in this series of Brahms’s complete A popular orchestral composer is seen in a more songs. -

Mark Hilliard Wilson St

X ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL X SEATTLE X 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 X 6:30 PM X MUSICAL PRAYER mark hilliard wilson St. James Cathedral Guitarist “Méditation” from Thaïs Jules Massenet 1842–1912 Etude No. 10 from 12 Etudes, Op. 6 Fernando Sor c. 1778–1839 Ave Maria Franz Schubert 1797–1828 Simple Gifts Joseph Brackett 1797–1882 Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Johann Sebastian Bach 1685–1750 Gymnopédie No. 1 from Trois Gymnopédies Erik Satie 1866–1925 Nigbati Iya Mi Ba Reriin Taiwo Adegoke “When my mother laughs” birth year unknown Theme from second movement ofNew World Symphony Antonín Dvořák 1841–1904 Prelude No. 1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier, BWV 846 J. S. Bach Woven World Andrew York b. 1958 Classical guitarist Mark Hilliard Wilson curates programs that explore the experiences of the heart through the ages, hoping to share some insight and reflection on our common humanity. He brings joy and technical finesse to the listener while integrating music from diverse backgrounds and different ages with a compelling story and a wry sense of humor. Performing regularly at festivals and concert series, Wilson has distinguished himself as a unique voice with programs that feature his own transcriptions of both the well-known and the obscure. Wilson’s compositions for the guitar have been appearing on stages throughout the Northwest US and Canada for over 15 years. He works in is the relatively unexplored genre of an ensemble of multiple guitars as the conductor, composer, arranger, and music director to the Guitar Orchestra of Seattle. Wilson has taught at Whatcom Community College and Bellevue College. -

Soundboardindexnames.Txt

SoundboardIndexNames.txt Soundboard Index - List of names 03-20-2018 15:59:13 Version v3.0.45 Provided by Jan de Kloe - For details see www.dekloe.be Occurrences Name 3 A & R (pub) 3 A-R Editions (pub) 2 A.B.C. TV 1 A.G.I.F.C. 3 Aamer, Meysam 7 Aandahl, Vaughan 2 Aarestrup, Emil 2 Aaron Shearer Foundation 1 Aaron, Bernard A. 2 Aaron, Wylie 1 Abaca String Band 1 Abadía, Conchita 1 Abarca Sanchis, Juan 2 Abarca, Atilio 1 Abarca, Fernando 1 Abat, Joan 1 Abate, Sylvie 1 ABBA 1 Abbado, Claudio 1 Abbado, Marcello 3 Abbatessa, Giovanni Battista 1 Abbey Gate College (edu) 1 Abbey, Henry 2 Abbonizio, Isabella 1 Abbott & Costello 1 Abbott, Katy 5 ABC (mag) 1 Abd ar-Rahman II 3 Abdalla, Thiago 5 Abdihodzic, Armin 1 Abdu-r-rahman 1 Abdul Al-Khabyyr, Sayyd 1 Abdula, Konstantin 3 Abe, Yasuo 2 Abe, Yasushi 1 Abel, Carl Friedrich 1 Abelard 1 Abelardo, Nicanor 1 Aber, A. L. 4 Abercrombie, John 1 Aberle, Dennis 1 Abernathy, Mark 1 Abisheganaden, Alex 11 Abiton, Gérard 1 Åbjörnsson, Johan 1 Abken, Peter 1 Ablan, Matthew 1 Ablan, Rosilia 1 Ablinger, Peter 44 Ablóniz, Miguel 1 Abondance, Florence & Pierre 2 Abondance, Pierre 1 Abraham Goodman Auditorium 7 Abraham Goodman House 1 Abraham, Daniel 1 Abraham, Jim 1 Abrahamsen, Hans Page 1 SoundboardIndexNames.txt 1 Abrams (pub) 1 Abrams, M. H. 1 Abrams, Richard 1 Abrams, Roy 2 Abramson, Robert 3 Abreu 19 Abreu brothers 3 Abreu, Antonio 3 Abreu, Eduardo 1 Abreu, Gabriel 1 Abreu, J. -

Download Download

МUSIC SUMMER FESTIVALS AS PROMOTERS OF THE SPA CULTURAL TOURISM: FESTIVAL OF CLASSICAL MUSIC VRNJCI Smiljka Isaković1, Jelena Borović-Dimić2 Abstract This paper is dedicated to the music summer festivals, a hallmark of the local community and the holder of the economic development of the region and the society, from ancient times to the present day. Special emphasis is placed on the International Festival of classical music "Vrnjci", held in Belimarković mansion in July, organized by the Homeland Мuseum – Castle of Culture of Vrnjaĉka Banja. A dramatic development of high technologies brought forth a new era based on conceptual creativity. Leisure time is prolonged, while tourism as one of the activities of spending leisure time is changing from passive to active. The cultural sector is becoming an important partner in the economic development of countries and cultural tourism is gaining in importance. Festival tourism in this country must be supported by the wider community and the state because the quality of cultural events makes us an equal competitor on the global tourism market. Keywords: cultural tourism, festivals, art, music, local self governments. Cultural Tourism The middle of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries can be called the period of tourism, since Stendhal popularized this term in France with his book "Memoirs of a tourist" (1838) and Englishman Thomas Cook opened his travel agency in 1841. Modern tourism experienced its first expansion between 1850 and 1870, enabled by the major railways networking in Europe -

Simon Powis, Guitar (Australia) New Opportunities for a Twenty-First Century Guitarist 6:00 - 7:15 P.M

The 16th Annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival June 3 - 5, 2016 Vieaux, USA SoloDuo, Italy Poláčková, Czech Republic Gallén, Spain De Jonge, Canada North, England Powis, Australia Davin, USA Beattie, Canada Presented by UITARS NTERNATIONAL G I in cooperation with the GUITARSINT.COM CLEVELAND, OHIO USA 216-752-7502 Grey Fannel HAUTE COUTURE Fait Main en France • Hand Made in France www.bamcases.com Welcome Welcome to the sixteenth annual Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival. In pre- senting this event it has been my honor to work closely with Jason Vieaux, 2015 Grammy Award Winner and Cleveland Institute of Music Guitar Department Head; Colin Davin, recently appointed to the Cleveland Institute of Music’s Conservatory Guitar Faculty; and Tom Poore, a highly devoted guitar teacher and superb writer. Our reasons for presenting this Festival are fivefold: (1) to help increase the awareness and respect due artists whose exemplary work has enhanced our lives and the lives of others; (2) to entertain; (3) to educate; (4) to encourage deeper thought and discussion about how we listen to, perform, and evaluate fine music; and, most important, (5) to help facilitate heightened moments of human awareness. In our experience participation in the live performance of fine music is potentially one of the highest social ends towards which we can aspire as performers, music students, and audience members. For it is in live, heightened moments of musical magic—when time stops and egos dissolve—that often we are made most conscious of our shared humanity. Armin Kelly, Founder and Artistic Director Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival Acknowledgements We wish to thank the following for their generous support of this event: The Cleveland Institute of Music: Gary Hanson, Interim President; Lori Wright, Director, Concerts and Events; Marjorie Gold, Concert Production Manager; Gina Rendall, Concert Facilities Coordinator; Susan Iler, Director of Marketing and Communications; Lynn M. -

Inhalt / Contents

Inhalt / Contents Grußwort / Greeting........................................... 7 II - Psalmvertonungen und Gebete / Vorwort / Preface................................................ 9 Psalm Settings and Prayers.............. 49 Ganz Europa im Fokus • Die Auswahl als repräsentativer Zeitspiegel und abgestimmt auf die heutige Praxis • Dominus regit m e.................................................. 50 Zur Gliederung der Chorstücke - Ein reichhaltiges Chorreper Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) toire • A cappella oder mit Begleitung? • Zur Interpretation - W ie der Hirsch schreiet / As the Hart Panteth.......... 58 Geistliche Chormusik im „langen 19. Jahrhundert" • Zur Heinrich Bellermann (1832-1903) Verwendung des Romantik-Begriffs im Titel des Chorbuchs • Editorische Anmerkungen - Zu den verwendeten Bibel Sicut cervus........................................................... 64 versionen • Hilfestellungen für die Probenarbeit Charles Gounod (1818-1893) All of Europe in the limelight • The selection as a represen Kot po mrzli studencini / As the Thirsting Hart Pants.. 67 tative reflection of the times, yet in tune with modern Hugolin Sattner (1851-1934) practice - The organisation of the choral pieces • A rich Sende dein Licht (Kanon) / and extensive choral repertoire • A cappella or with accom Send Out Thy Light (Canon)............................... 68 paniment? • Concerning performance • Sacred choral music Friedrich Schneider (1786-1853) in the "long nineteenth century" • On the use of the term "Romantik" in the title of this choir -

The Solo Classical Guitar Concerto

The solo classical guitar concerto: A soloist’s preparatory guide to selected works by Josina Nina Fourie-Gouws © University of Pretoria The solo classical guitar concerto: A soloist’s preparatory guide to selected works by Josina Nina Fourie-Gouws A mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Music (Performing Art) Department of Music Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Professor Wessel van Wyk Co-supervisor: Abri Jordaan September 2017 © University of Pretoria ABSTRACT The study addresses the preparatory information needs of potential performers of solo classical guitar concerti. Identifying a range of specific decisions that play an important part in the pre-performance planning of an anticipated concerto performance provides performance considerations for each selected concerto. The content of six solo classical guitar concerti spanning almost 180 years by six composers from four countries was analysed for the purpose of this study. Two early guitar concerti by guitarist composers Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829) and Ferdinando Carulli (1770-1841), two modern concerti by non-guitarist composers Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968) and Joaquín Rodrigo (1901-1999) and two modern concerti by guitarist composers Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) and Leo Brouwer (b.1939) were investigated. The study examines specific compositional and performance aspects of each concerto to serve as a guideline for professional performers, students and teachers. Each concerto was analysed according to similar themes: the historical significance of the investigated concerti, pre-performance considerations, the level of difficulty of selected concerti, technical observations, performance recommendations and observations regarding balance between the soloist and orchestra. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

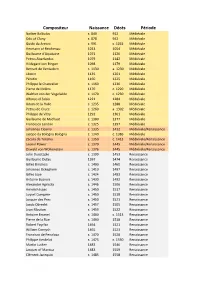

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

Preservation and Study of Historical Guitars Museu De La Musica, Catalunya : Methodology Proposal to Play the Unplayable

Preservation and Study of Historical Guitars Museu de la Musica, Catalunya : Methodology Proposal to Play the Unplayable Toros Ufuk Senan MASTER THESIS UPF / 2014 Master in Sound and Music Computing Master Thesis Supervisor: Enric Guaus, Paul Poletti Department of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona ii Preservation and Study of Historical Guitars Museum de la Musica : Methodology Proposal to Play the Unplayable Toros Ufuk Senan Philips Electronic Nederlands High Tech Campus 36, p.118 5656 HA Eindhoven, Netherlands Master's thesis Abstract WoodMusick project is a multi-disciplinary COST action research project. The main goal of the project is to study museum instruments and preserve their physical and acoustical properties. This paper aims to contribute the project by studying historical guitars in Museu de la Musica, Catalunya, as well as to propose a global measurement methodology for prediction of acoustical properties of guitars during the design stage. Two historical classical guitars, Torres 625 from Antonio de Torres and Labrador from romantic period are studied, in addition to a test guitar. Steady-state and impulse responses are recorded and spectral and physical properties are extracted from recordings. The results are classified with WEKA by ESSENTIA descriptors and two guitars are succefully identified and distinguished from each other. Extracted features and physical properties are observed in the latter stage and sound feature estimations are proposed.Besides the multi disciplinary nature of the study is already a challenging task, the main obstacle turned out to be to build a methodology that ensures safety of the instrument while collecting the necessary data. -

A Comprehensive Guitar Series

Bridges TM A Comprehensive Guitar Series “This new edition, in my opinion, is very close to being THE definitive word on classical guitar instruction – period.” Patrick Kearney, international concert artist and professor of classical guitar at Vanier College and Concordia University Bridges TM Introduction Bridges™ is the fourth edition of the renowned Guitar Series, originally published in 1989 to international acclaim. This edition aims to provide students with a clear, well-paced route for their musical development; to nurture the technique necessary to successfully meet those developmental challenges; and to expose students to the full range of the instrument’s repertoire. The chosen repertoire and studies at any given level fall within a carefully sequenced range of technical and musical difficulty. From the late elementary to early advanced levels students can be assured that their learning path will be well rounded and complete. Some of the most notable features of Bridges™ are: the inclusion of guitar masterpieces by such beloved guitar composers as Agustín Barrios, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and Leo Brouwer minimal fingering suggestions, leaving teachers more flexibility and a clearer score from which to work a balance of style choices for repertoire and studies in all levels The well-rounded guitarist will have an understanding of the instrument’s history as well as practical experience with a wide range of repertoire from all historical periods and styles. Guided by this principle, the series editors have drawn on more than 500 years’ worth of guitar and lute music. Each book features compositions from the Renaissance to the present day; by learning music from each style period, students will gain a comprehensive overview of the evolution of musical styles.